The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience, by Francisco Varela, Evan Thompson, and Eleanor Rosch, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991, 328pp, $25 cloth

Cognitive science, as an interdisciplinary school of thought, may have recently moved beyond the bandwagon stage onto the throne of orthodoxy, but it does not make a favorable first impression on many people. Familiar reactions on first encounters range from revulsion to condescending dismissal--very few faces in the crowd light up with the sense of "Aha! So that's how the mind works! Of course!" Cognitive science leaves something out, it seems; moreover, what it apparently leaves out is important, even precious. Boiled down to its essence, cognitive science proclaims that in one way or another our minds are computers, and this seems so mechanistic, reductionistic, intellectualistic, dry, philistine, unbiological. It leaves out emotion, or what philosophers call qualia, or value, or mattering, or . . . the soul. It doesn't explain what minds are so much as attempt to explain minds away.

This deeply felt dissatisfaction with cognitive science has many grounds--some good, some preposterous--improperly jumbled together in a knot of anxiety. When you get right down to it, many people just don't like the idea of their minds as computers, and hence are strongly inclined to endorse any champion who will stand fast against this deplorable juggernaut. So critics of cognitive science, especially if they take themselves to be radical or revolutionary critics, must be uncommonly surefooted if they are to avoid being swept up in the more hysterical campaigns. And defenders of cognitive science must be uncommonly discriminating, and not just brand every critic a crypto-dualist, a vitalist, a Mysterian, for while the most vocal critics to date have often richly deserved these epithets, there are other, more thoughtful critics who do not. Moreover--truth to tell--even a crypto-dualist can stumble into an important insight on occasion.

Francisco Varela, an immunologist-turned-neuroscientist, Evan Thompson, a philosopher, and Eleanor Rosch, a psychologist, are radical critics of cognitive science, calling for what they consider to be more of a revolution than a set of reforms, and they have pooled their skills to execute what is surely the best informed, best balanced radical critique to date. Just how radical? Their heroes are the Buddha and the French phenomenologist, Maurice Merleau-Ponty. They argue that Buddhist meditative traditions offer not just a wealth of important phenomena of human consciousness, but otherwise unobtainable insights into the relations of embodiment that permit us to understand how the inner and the outer, the first-person point of view and the objective point of view of science, can coexist.

Cognitive scientists standardly assume a division between independently existing ("pregiven") "external" objects, properties and events on the one hand and their "internal" representations in symbolic media in the mind/brain on the other. Varela et al. propose to replace this with an "enactive" account. The fundamental differences are encapsulated in answers to three questions:

Question 1: What is cognition?

Cognitivist Answer: Information processing as symbolic computation--rule-based manipulation of symbols.

Enactivist Answer: Enaction. A history of structural coupling that brings forth a world.

Question 2: How does it work?

Cognitivist Answer: Through any device that can support and manipulate discrete functional elements--the symbols. The system interacts only with the form of the symbols (their physical attributes), not their meaning.

Enactivist Answer: Through a network consisting of multiple levels of interconnected, sensorimotor subnetworks.

Question 3: How do I know when a cognitive system is functioning adequately?

Cognitivist Answer: When the symbols appropriately represent some aspect of the real world, and the information processing leads to a successful solution to the problem given to the system.

Enactivist Answer: When it becomes part of an ongoing existing world (as the young of every species do) or shapes a new one (as happens in evolutionary history) (pp 42-3, 206-7)

Well, what do the Enactivist answers mean? Is this really revolutionary or is it just a modest revision of emphases in response to an assemblage of familiar criticisms? Or it is perhaps the assemblage that is revolutionary? Have the various piecemeal critics failed to see how radical the effect of their mass action might be? The authors try to make us believe this more exciting verdict, but they are so scrupulous and sympathetic in their gleaning from others that they provide all the ammunition one would need to rebut their revolutionary call. Reform, as we know, is the enemy of revolution, and as an ardent reformer, I must say that they have not convinced me. I think I can proceed with business-as-usual cognitive science, but I am genuinely grateful to them for a variety of important nudges away from admittedly deplorable--but optional--features of standard cog-sci dogma.

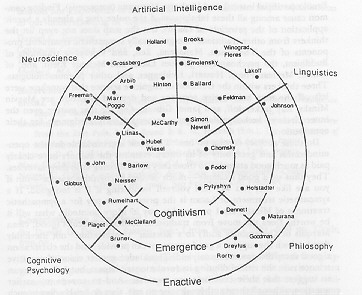

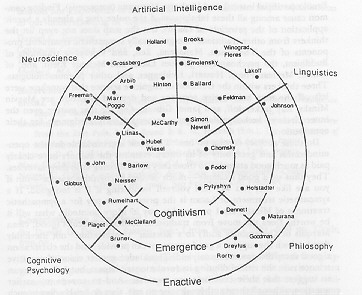

The authors locate their own project with the help of a polar coordinate map of cognitive science, a descendant of my "view from the East Pole" (Dennett, 1986), showing the location in logical space of the principal contributors, as they interpret them.

Their project is to consolidate the outer ring of Enactive theory, and one can see at a glance that this is going to involve being somehow farther out than the "Emergentists" of the middle ring: such critics of various aspects of cognitive science as Ulric Neisser (the Apostate--1976, not the Founder--1967), the connectionists, and Douglas Hofstadter and myself. (The Emergentists' canonical answers to the three-question catechism above are given on page 99).

Another glance at the map shows that uniting the outer sanctum of Enactivists is going to require the amalgamation of ideas drawn from extraordinarily diverse sources: the psychologists Jean Piaget and Jerome Bruner, the neuroscientists Walter Freeman and Stephen Grossberg, the linguist George Lakoff, the philosophers Richard Rorty and Hubert Dreyfus, and such hard-to-classify thinkers as John Holland (genetic algorithms), Rodney Brooks (artificial insects), and Umberto Maturana (autopoesis). Finding common cause amongst all these inhabitants of the outer ring is already a heroic application of the principle of charity, but the map does not even list the thinkers from other traditions who get equally sympathetic treatment: the Therevada, Mahayana, Zen, and Vajrayana traditions of Buddhism, the psychoanalysts Jacques Lacan and Melanie Klein, and of course Merleau-Ponty, Husserl, Heidegger, and other phenomenomologists. Three thinkers within the tradition of cognitive science that somehow were left off the map but receive accurate and detailed attention are Marvin Minsky, Ray Jackendoff and James Gibson. And for that matter, even the inner circle of arch-cognitivists get a respectful acknowledgment for their contributions.

Don't these authors despise anybody? The book is remarkable for the openmindedness and generosity of its interpretations; the authors have clearly paid as much good attention to those they are criticizing as to their favorites. They thus set a good example--much needed in cognitive science--but if you are like me you will find yourself wondering if it is too good. If a sympathetic treatment of Lacan is the price I must pay for a sympathetic treatment of Minsky, am I prepared to pay it? More pointedly, what will it be worth? Doesn't the move from traditional academic fisticuffs (good, clean Marquis of Queensbury stuff) to a Rortian "conversation" inevitably devalue both the support a good argument can provide, and the clarification a good sharp disagreement can yield? This kinder, gentler vision of cognitive science runs the risk of diluting its revolutionary impact, but I don't mean to suggest that their criticisms are toothless. And to answer my earlier question, while these authors despise no one, they do briskly dismiss such critics as Popper and Eccles, and Roger Penrose, on p.129.

As best I can see, the heart of the authors' argument for the need for revolution, which I don't yet fully understand, has to do with what happens when cognitive science faces up to one of its own implications: there is no Self:

. . .to the extent that research in cognitive science requires more and more that we revise our naive idea of what a cognizing subject is (its lack of solidity, its divided dynamics, and its generation from unconscious processes), the need for a bridge between cognitive science and an open-ended pragmatic approach to human experience will become only more inevitable. Indeed, cognitive science will be able to resist the need for such a bridge only by adopting an attitude that is inconsistent with its own theories and discoveries. (p.127)I think I have recently produced just such a consistent cognitive science theory of consciousness with no "solid" Self (Dennett, 1991). One of the co-authors of The Embodied Mind, Evan Thompson, worked with me during 1990-91, as a Visiting Fellow at the Center for Cognitive Studies at Tufts, while both my book and theirs were in the late stages--too late--of the publication process, so neither side has had a proper chance yet to digest and respond to the other. Of course maybe I should stop viewing my book as a conservative extrapolation of the gains of cognitive science, and start considering myself a fellow revolutionary. There are some points of striking consonance--see especially our parallel accounts of the nature (physical, metaphysical, epistemological) of color. As the great diversity of the outer ring roster of Enactivists of figure 1.1 suggests, one could well be an Enactivist without realizing it.

But it still seems to me that the authors protest too much. In their explanation of the key term, "enactive", they draw heavily on the claims by the geneticist Richard Lewontin that evolution must be understood from an enactive perspective. Lewontin deplores the way adaptationists help themselves to the oversimplification of an external and "pregiven" environment that sets problems for the organism. On the contrary, Lewontin typically insists, the organism plays an important role in creating and constituting its own environment. Varela et al. make a parallel claim about the role of the organism in "bringing forth a world". When David Marr (1982) influentially encourages us to treat visual systems as solving the problem of "inverse optics"--how does the organism recover the truth about the visible properties independently out there in its environment?--he helps himself to an oversimplification. There is something to this, of course, but just how important is it? What are the relative proportions of organismic and extra-organismic contributions to the "enacted" world? It is true, as Lewontin has often pointed out, that the chemical composition of the atmosphere is as much a product of the activity of living organisms as a precondition of their life, but it is also true that it can be safely treated as a constant (an "external", "pregiven" condition), because its changes in response to local organismic activity are usually insignificant as variables in interaction with the variables under scrutiny. The same is true of the color of objects: they have indeed coevolved with the color-vision systems of the organisms that perceive them, but, except on an evolutionary time scale, they are in the main imperturbable by organisms' perceptual activity. Once we have this metaphysical point duly corrected and secured, does it play much of a role in ongoing cognitivist research?

The authors recognize that they need to respond to this hard-headed demand that they demonstrate that their view is not just "a refined, European-flavored position that has no hands-on applications in cognitive science." (p.207) If Marr's "inverse optics" is a Bad Example, what is a Good Example? Rodney Brooks' "Intelligence without Representation." (1987). The trouble is that once we try to extend Brooks' interesting and important message beyond the simplest of critters (artificial or biological), we can be quite sure that something awfully like representation is going to have to creep in like the tide, in large waves. Will our Enactive Enlightenment lead us to say different sorts of things about these sorts of cognitive states, events and processes? Probably. Very different--revolutionarily different? It is too soon to say, so we won't know for awhile whether we need, or are in the midst of, a revolution in cognitive science. In the meantime the authors find many new ways of putting together old points that we knew were true but didn't know what to do with, and that in itself is a major contribution to our understanding of cognitive science.

Dennett, D. C., 1986, "The Logical Geography of Computational Approaches: a View from the East Pole," in M. Brand and R. M. Harnish, eds., The Representation of Knowledge and Belief, Tucson, Univ. of Arizona Press, pp. 59-79.

Dennett, D. C., 1991, Consciousness Explained, Boston: Little Brown.

Marr, D., 1982, Vision, San Francisco: Freeman.

Neisser, U., 1967, Cognitive Psychology, New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Neisser, U., 1976, Cognition and Reality, San Francisco: Freeman.