The Operant Conditioning of Human Motor Behavior

A very large body of experimental results have accumulated in the field of operant, or instrumental, conditioning of the rat, the pigeon, and of other experimental animals. The application to human behavior of the laws generated by such research is most often done by the use of theory. An alternative method is to demonstrate that the manipulation of classes of empirically defined variables that produce specific and highly characteristic changes in the behavior of small experimental animals in Skinner boxes produce similar changes in the behavior of college students.

This paper reports procedures for the direct application of the variables defining the paradigm for operant conditioning to human behavior and shows that human beings act very much indeed like experimental animals when they are subjected to the same experimental treatments. It suggests that direct application of conditioning principles to some categories of human behavior may be justified. The procedures are simple and they may be followed by anyone, with a minimum of equipment.

That it is possible to condition human motor behavior will surprise few who are concerned with behavior theory. Nevertheless, it has not always been clear what behaviors will act as "responses," what events will prove to be "reinforcing stimuli," or exactly what procedures would most readily yield reproducible results. This paper describes methods that have been worded out for easy and rapid operant conditioning of motor behavior in humans, states characteristic findings, and reports sample results. Developed in a series of exploratory experiments in an elementary laboratory course in psychology, the methods may have a wider utility.

Development of the Method

In one year's class in the introductory laboratory, an attempt was made to reproduce the Greenspoon effect (1), in which the rate of saying plural nouns is brought under experimental control by the use, as a reinforcing stimulus, of a smile by the experimenter, or by his saying "Mmmm," or "Good." The results were indifferent: a few students had good success with some subjects; the majority failed with all their subjects. The successful students seemed, casually, to be the best-looking, most mature, and most socially acceptable; they tended to have prestige. This suggested that the procedure was effective because S "cared" about E's behavior; that is, he noticed and responded in one way or another to what E said or did.

This observation is consistent with the Guthrian (but Skinner-box-derived) view that if one could isolate any single property shared by reinforcing stimuli (whether "primary" or "secondary"), it would prove to be that all reinforcing stimuli produce a vigorous response of very short latency (2). Greenspoon's procedure was therefore modified to force S to respond to the stimuli that E wished to use as reinforcers. Thereafter, the incidence of failures to condition human Ss dropped considerably.

Using these methods, many kinds of stimuli have been found to be reinforcing in the hands of student experimenters, and a wide variety of responses have been conditioned. Data have been gathered on performance under regular reinforcement, and under such other schedules as variable and fixed interval, and variable and fixed ratio (3, 4), both in establishing rates of response and in yielding extinction curves of appropriate form after the termination of reinforcement. Experiments have been done on response differentiation, discrimination training and chaining. Indeed, there is reason to believe that the whole battery of operant phenomena can be reproduced in a short time. Incidental data have been obtained on "awareness," "insight," or what-have-you.

Here is a sample set of instructions to E for human conditioning. In presenting the method more fully, we shall amplify each section of these instructions in turn.

Procedure: Human Operant Motor Conditioning

1. Instruction to subject: "Your job is to work for points. You get a point every time I tap the table with my pencil. As soon as you get a point, record it immediately. You keep the record of your own points--try to get as many as possible." As necessary: "I'm sorry, I can't answer any questions. Work for points." DO NOT SAY ANYTHING ELSE TO S. Avoid smiling and nodding.

2. Reinforcing stimulus: pencil tap.

3. Response: tapping forefinger to chin. Be sure the tap on the chin is complete before reinforcing--that is, be sure that S has tapped his chin and withdrawn his finger. During regular reinforcement, be sure S does not "jump the gun" and record a point before you give it to him. If S does this, withhold reinforcement and say: "You got no point that time. You get a point only when I tap the table. Be sure you get a point before recording."

4. Procedures: Observe S; determine operant level of chin-tapping before giving instructions.

a. Approximation conditioning of chin-tap (described later).

b. 100 regular reinforcements of chin-tap.

c. Shift to:

[1/2 of the subjects] 30-second fixed interval reinforcement.

[1/2 of the subjects] fixed ratio reinforcement at ratio given by Ss rate per 30 seconds.

[When shifting from regular reinforcement to the schedule, make sure that S doesn't extinguish. If his rate has been high, you'll have to shift him, perhaps, to a 20:1 ratio--with such a change, S will probably extinguish. Prevent this by shifting him first to a 5 : 1 ratio (for 2 minutes), then to 10 : 1 (for 2 minutes), then to 20 : 1. Similarly, put S on 10 second F. I., then a 20-second F. I., and finally on a 30-second one.]

Continue for 500 responses.

d. Extinguish to a criterion of 12 successive 15-second intervals in which S gives not more than 2 responses in all.

5. Subject's "awareness":

[1/4 of S's] Record any volunteered statement made by S.

[1/4 of S's] At the end of the experiment, ask, "What do you think was going on during this experiment? How did it work?"

[1/4 of S's] Add to instructions: "When you think you know why you are getting points, tell me. I won't tell you whether you're right or wrong, but tell me anyway." At about the middle of each procedure, ask, "What do you think we are doing now?"

[1/4 of S's] At the beginning of each procedure, give S full instructions:

a. "You'll get a point every time you tap your chin, like this." (Demonstrate.)

b. "From now on, you'll get a point for every twentieth response," or "... for a response every 30 second." "From now on, you'll get no more points, but the experiment will continue."

6. Records:

a. Note responses reinforced during approximation; record time required, and number of reinforcements given.

b. Record number of responses by 15-second intervals. Accumulate.

c. Draw cumulative response curves.

d. Be sure your records and graphs clearly show all changes in procedure, and the points at which S makes statements about the procedure.

e. Compute mean rates of response for each part of the experiment.

f. Record all spontaneous comments of S that you can; note any and all aggressive behavior in extinction.

General Notes

Duration and situation. As short a time as 15 minutes, but, more typically, a period of 40 to 50 minutes can be allotted to condition an S, to collect data under regular and partial reinforcement schedules, to develop simple discriminations, and to trace through at least the earlier part of the extinction curve. The experiment should not be undertaken unless S has ample time available; otherwise Ss tend to remember pressing engagements elsewhere when placed on a reinforcement schedule. We have not tried, as yet, to press many Ss very much beyond an hour of experimentation.

The experiments can be done almost anywhere, in a laboratory room, in students' living quarters, or in offices. Background distractions, both visual and auditory, should be relatively constant. Spectators, whether they kibitz or not, disturb experimental results.

The E may sit opposite S, so that S can see him (this is necessary with some reinforcing stimuli), or E may sit slightly behind S. S should not be able to see E's record of the data. In any case, E must be able to observe the behavior he is trying to condition.

Subject and experimenter. Any cooperative person can be used as a subject. It does not seem to matter whether S is sophisticated about the facts of conditioning; many Ss successfully conditioned, who gave typical data, had themselves only just served as Es . However, an occasional, slightly sophisticated S may try to figure out how he's "supposed to behave" and try to "give good data." He will then emit responses in such number and variety that it is difficult for E to differentiate out the response in which he is interested.

People who have had some experience with the operant conditioning of rats or pigeons seem to become effective experimenters, learning these techniques faster than others. The E must be skilled in delivering reinforcements at the proper time, and in spotting the responses he wants to condition. With his first and second human S, an E tends to be a little clumsy or slow in reinforcing, and his results are indifferent. About a third of our students are not successful with the first S. Practice is necessary.

Apparatus. The indispensable equipment is that used by E to record: a watch with a sweep second hand, and paper and pencil. Beyond these, the apparatus man can have a field day with lights, bells, screens, recorders, and so on. This is unnecessary.

Instructions

Conditioning may occur when no instructions whatever are given, but it is less predictable. The instructions presented here give consistent success.

Subjects may be told that they are participating in a "game," an "experiment," or in "the validation of a test of intelligence." All will work. Spectacular results may be achieved by describing the situation as "test of intelligence," but this is not true for all Ss.

In general, the simpler the instructions the better. No mention should be made that S is expected to do anything, or to say anything. Experience suggests that if more explicit instruction is given, results are correspondingly poor. Elaborate instructions tangle S up in a lot of verbally initiated behavior that interferes with the conditioning process.

The instructions will be modified, of course, to fit the reinforcement. It seems to be important for S to have before him a record of the points he has earned. (This is not, of course, E's record of the data.) It seems to be better if he scores himself, whether by pressing a key that activates a counter, or by the method described here. Most Ss who do not have such a record either do not condition, or they quit working.

Reinforcing Stimuli

Any event of short duration whose incidence in time is under the control of E may be used as a reinforcing stimulus if S is instructed properly. The most convenient is the tap of a pencil or ruler on a table or chair arm, but E may say "point," "good," and so on. Lights, buzzers, counters, all work. One student found that getting up and walking around the room and then sitting down was a very effective reinforcer for his instructed S. ("Make me walk around the room.")2

The E may assign a "value" to the reinforcing stimulus in the instructions--e.g., for each 10 points S gets a cigarette, a nickel, or whatever. Members of a class may be told that if they earn enough points as Ss, they may omit writing a lab report.

Where no instructions are given, or where the instructions do not provide for an explicit response to a reinforcing stimulus (as in the Greenspoon experiment--i.e., when E wished to use a smile, or an "mmmm," with the intention of showing "learning without awareness") many Ss will not become conditioned.

The most important features of the operation of reinforcement are (a) that the reinforcing stimulus have an abrupt onset, (b) that it be delivered as soon as possible after the response being conditioned has occurred, and (c) that it not be given unless the response has occurred. Delayed reinforcement slows up acquisition; it allows another response to occur before the reinforcement is given, and this response, rather than the chosen one, gets conditioned. The best interval at which to deliver a reinforcing stimulus seems to be the shortest one possible--the E's disjunctive reaction time.

When S has been conditioned and is responding at a high rate, he may show "conditioned recording"--i.e., he will record the "point" before E has given it to him. The E must watch for this.

When S can observe E, it is entirely possible that Ss behavior is being reinforced, not by the chosen reinforcing stimulus, but by others of E's activities, such as intention movements of tapping the table, nods of the head, and recording the response. The effect of such extraneous reinforcers can be easily observed during extinction, when the designated reinforcing stimulus is withdrawn. The precautions to be taken here will depend upon the purpose of the experiment. The E should thus remain as quiet and expressionless as possible.

The Response

The E has great latitude in his choice of behavior to be conditioned. It may be verbal or motor, it may be a response of measurable operant level before reinforcement, it may be a complex and infrequent response that S seldom, if ever, has performed. One qualification is that the response must be one that terminates relatively quickly, so that reinforcement can be given. (One E conditioned an S to bend his head to the left, reinforcing when the head was bent. The S held his head bent for longer and longer times, and so got fewer and fewer reinforcements as the procedure became effective. He became "bored" and stopped working.)

Motor behavior. The E may observe S for a few minutes before proposing to do an experiment on him and choose to condition some motor behavior S occasionally shows, such as turning his head to the right, smiling, or touching his nose with his hand.

The E will then first determine its operant level over a period of time before he starts to reinforce. Here, changes in rate of response as a function of the reinforcement variables demonstrate conditioning. Such behavior is easily conditioned without awareness.

The E may decide in advance on a piece of S's behavior he wishes to condition. In this case, he may choose something like picking up a pencil, straightening his necktie, and so on. If E chooses something as simple as this, he can usually afford to sit and wait for it to occur as an operant. If it does not, he may find it necessary to "shape" the behavior, as will be necessary if he chooses a relatively or highly unlikely piece of behavior, such as turning the pages of a magazine, slapping the ankle, twisting a button, looking at the ceiling, placing the back of the hand on the forehead, writing a particular word, or assuming a complex posture.

Many of the readers will question this use of the word "response." It is being used in accordance with the definition made explicit in Skinner's The Behavior of Organisms:

Any recurrently identifiable part of behavior that yields orderly functional relationships with the manipulation of specified classes of environmental variables is a response.

So far, this concept has proven a useful one: We have not explored the "outer limits" of the concept, with respect either to the topography or to the consequences of the behavior--we have not sampled broadly enough to find parts of behavior tentatively classifiable as responses that didn't yield such functions when we tried to condition them.

The contingencies of reinforcement, established in advance by E, determine the specifying characteristics of a response: He may reinforce only one word, or one trivial movement. In this case, he gets just that word or movement back from S. If E reinforces every spoken sentence containing any word of a specifiable class (e.g., the name of an author) he gets back from S a long discussion of literary figures. Plotted cumulatively, instances of naming of authors and titles in a whole sentence behave as a response class. By restricting reinforcement to naming one author, the discussion is narrowed. This method may serve fruitfully in research on what some call "response-classes" and others call "categories of behavior."

Procedures

Approximation conditioning ("shaping"). When the conditioning procedure begins, some Ss will sit motionless and silent for some minutes after the instructions, but sooner or later they will emit responses that can then be reinforced. Such a period of inactivity, although trying to both S and E, does not seem to disturb the final results.

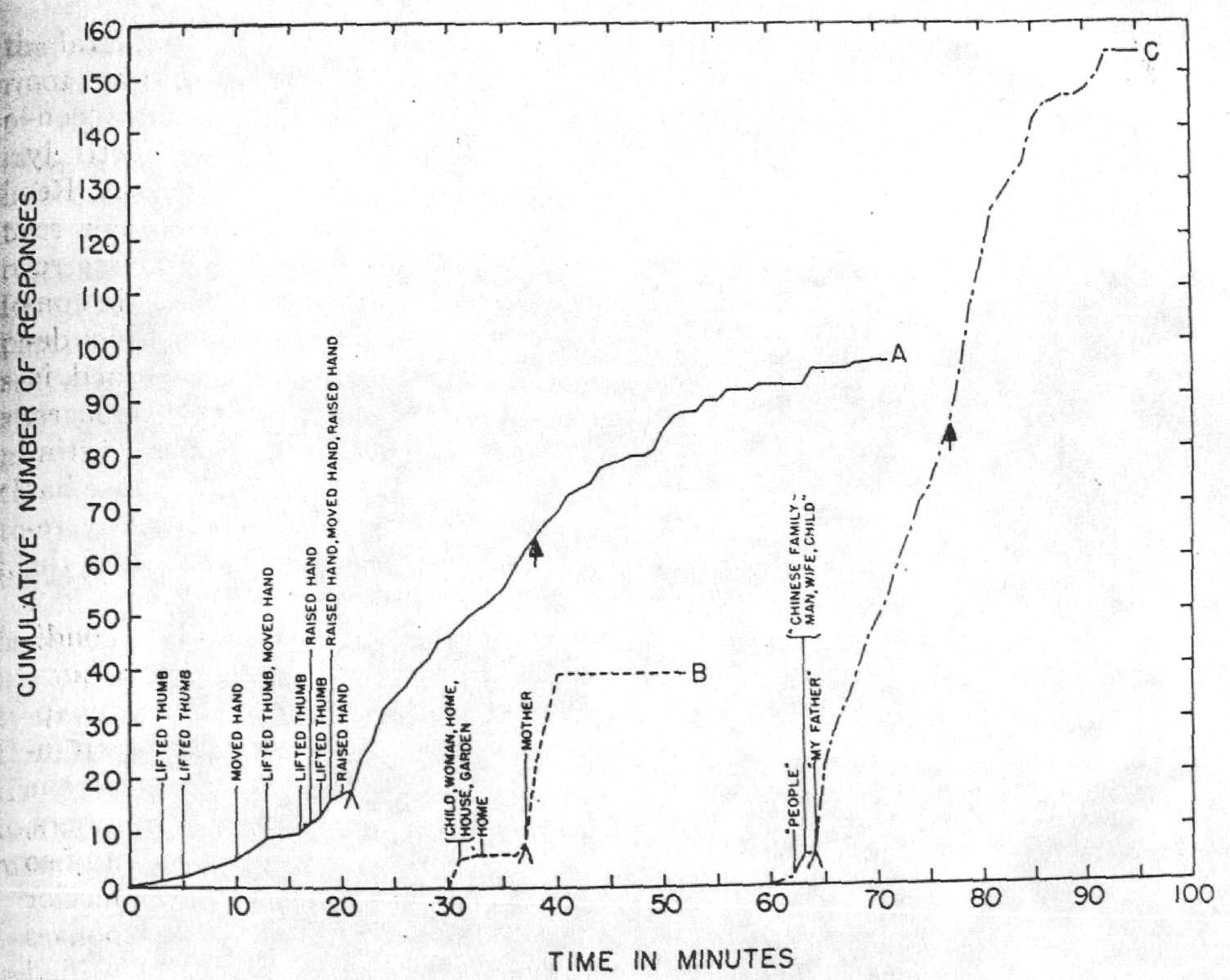

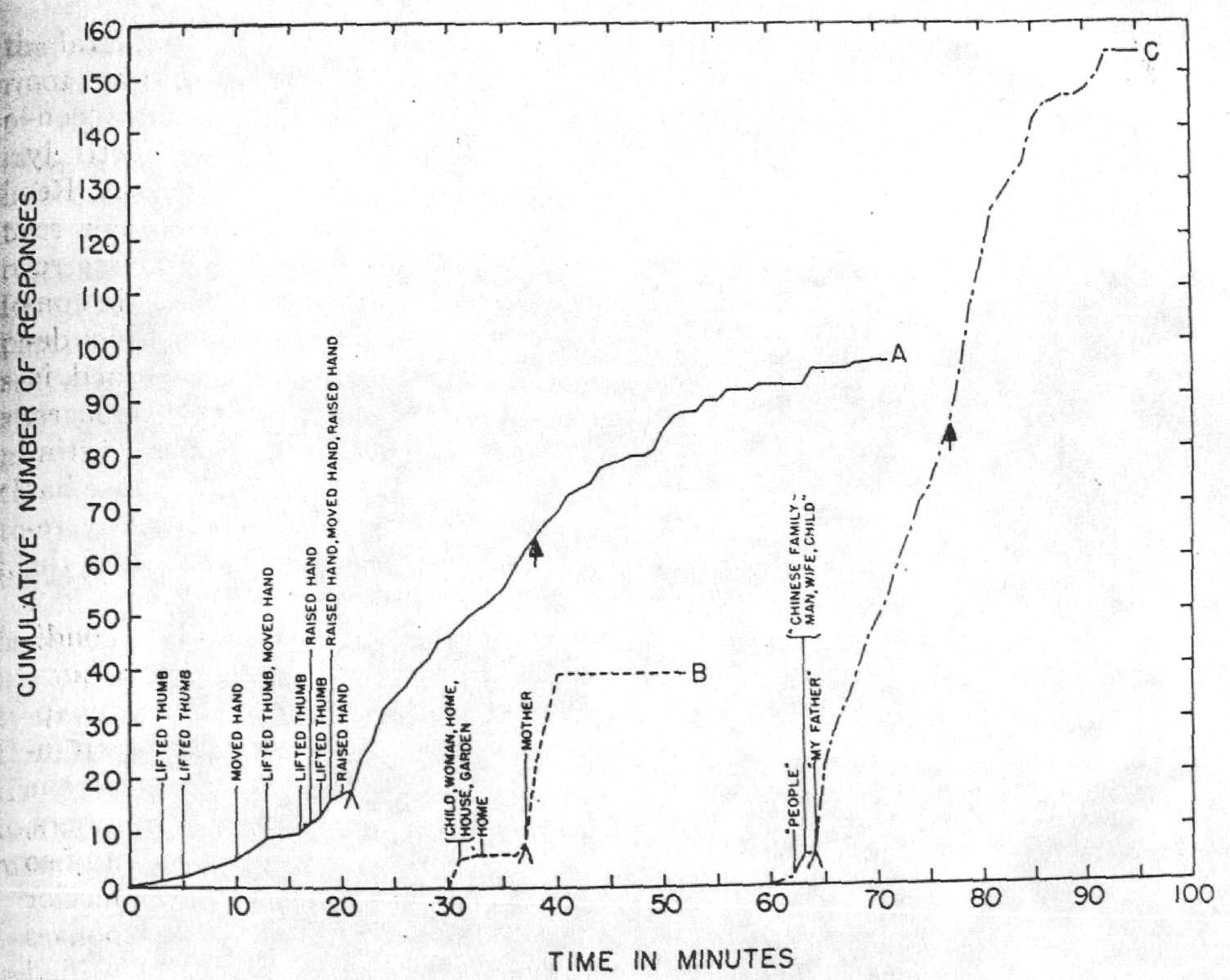

Fig. 1. Approximation Conditioning, Followed by Regular Reinforcement

Curves B and C shifted 30 and 60 minutes along X-axis respectively. During the approximation phase, the responses reinforced are named. Following the carat, only the specified R is reinforced.

(A) R: raising hand. SR: pencil tap, recorded by S. Following arrow, no response is reinforced.

(B) R: saying word referring to member of S's immediate family. SR: pencil tap, recorded by S. At sharp break, S says, "You've got me talking about my family, and it's none of your business," sits silent, and then changes subject and talks about other matters. In later inquiries, it developed that S had been worried about an alcoholic brother.

(C) R and SR same as Curve B, another S. Following arrow, no response is reinforced.

If the response chosen has a high operant level and occurs soon, E will proceed to regular reinforcement. Otherwise, he will find it necessary to "shape" the behavior, a process that is usually complete in 10, but may take as many as 25 minutes. In this procedure, E reinforces responses that are successively more and more like the response selected for conditioning3 (Fig. 1. A). This procedure requires skill and often bears a close (and not accidental) resemblance to the child's game of "Hot or Cold," and to the adult's "Twenty Questions, " as well as to the procedure used in conditioning rats and pigeons. It is perhaps best explained by example:

Let us suppose that E has decided to condition a response such as taking the top off his fountain pen and putting it back on again. The E first reinforces the first movement he sees S make. This usually starts S moving about. Then he will reinforce successively movement of the right hand, movement toward the fountain pen, then touching the pen, lifting it, taking the top off, and finally taking the top off and putting it back on. The effect of a single reinforcement in shifting, in narrowing down the range of a subject's activity, can be interesting to observe. It tempts E to depart from the procedure originally planned and to spend this time successively differentiating out more and more unlikely pieces of behavior.

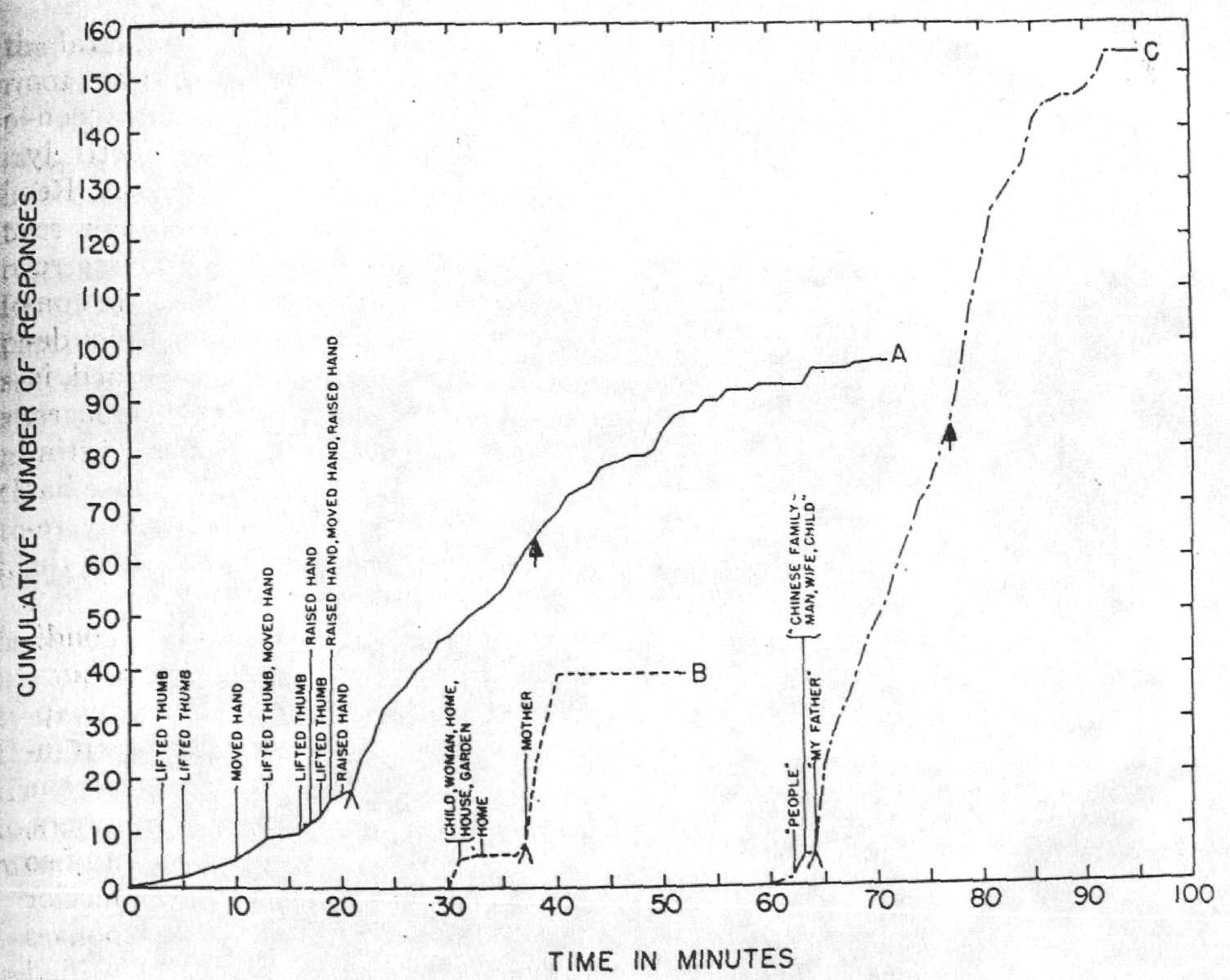

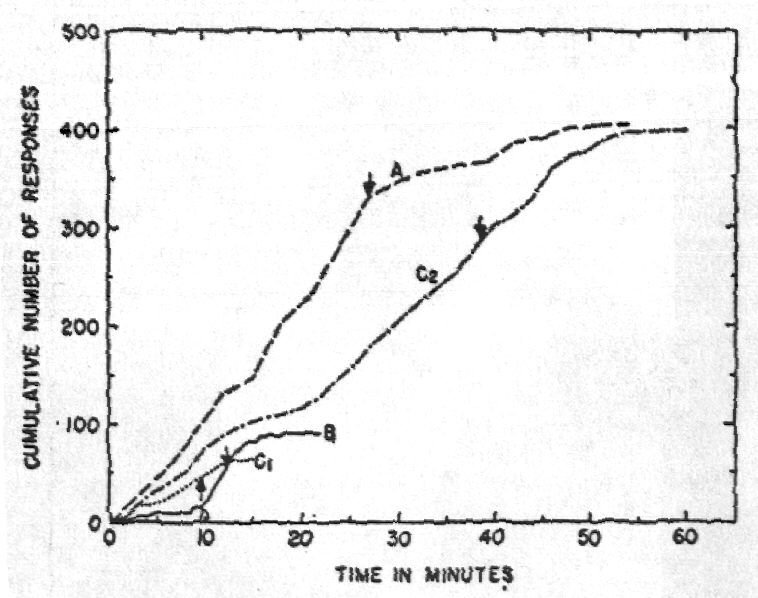

Fig. 2. Regular Reinforcement and Subsequent Extinction

For curves A1, C2, and C2 at t=0, reinforced response given for the first time (approximation phase omitted). From t=0 to arrow, regular reinforcement. Following arrow, no reinforcement.

Fig. 2. Regular Reinforcement and Subsequent Extinction

For curves A1, C2, and C2 at t=0, reinforced response given for the first time (approximation phase omitted). From t=0 to arrow, regular reinforcement. Following arrow, no reinforcement.

(A) R: touching left hand to right ankle.

(B) R: naming book title or author. SR: pencil tap, recorded by S. Approximation conditioning to carat; then regular reinforcement of R only.

(C1) R: folding hands. SR: pencil tap, recorded by S. Verbalization occurs after maximum rate is achieved.

(C2) same curve as C1, with scales of both abscissa and ordinate multiplyed by constants to yield a curve comparable to Curve A.

It requires skill to shape behavior rapidly, whether one deals with rats, pigeons, or men. If E demands too much of S--that is, if he withholds reinforcement too long, S's responses may extinguish. If E is too liberal--if he reinforces responses that are too similar to one another--he may condition these responses so effectively that further progress is slow. Responses that are conditioned as a result of E's lack of skill in spacing reinforcements, like those that are conditioned when E is sluggish in delivering reinforcement, are termed, in lab slang, "superstitious" responses. Even after they have been extinguished and the correct response has been conditioned, they typically reappear during later extinction of the conditioned operant.

Verbal behavior is readily conditioned, and by the same techniques. Almost invariably, in this case, shaping is necessary unless S has been instructed to "say words," or unless the verbal response is saying numbers, such as "two," "twenty-five," and so on. When E shapes verbal behavior he should preselect verbal responses that can be unequivocally identified in a stream of language, as for example, saying "aunt," "uncle," or the name of any member of a family, or saying names of books and authors (even in a particular field, as E chooses). By reinforcing sentences containing these words, E achieves control of a topic of conversation (Fig. 1. B and C). The E may also bring S to say, and to say repeatedly, particular quasi-nonsense sentences, such as: "I said that he said that you said that I said so." The Ss may be conditioned to count, to count by threes, or backwards by sevens, and so on, when shaping is used.

Regular reinforcement (Fig. 2). Once the response occurs, E will first reinforce it regularly. One hundred regular reinforcements have proven ample to build up a resistance to extinction sufficiently great to permit E to shift S to most schedules without risk of extinction. (As Fig. 2 shows, the number of R's in extinction is roughly proportional to the number of regular reinforcements in this range of values.) This number of reinforcements is also entirely adequate to yield a high and stable rate of response. "One-trial" conditioning, found in the rat and pigeon with comparable procedures, often shows itself: The rate of response assumes its stable value after a single reinforcement of the chosen response. When this occurs, S is not necessarily able to state what he is doing that yields him points.

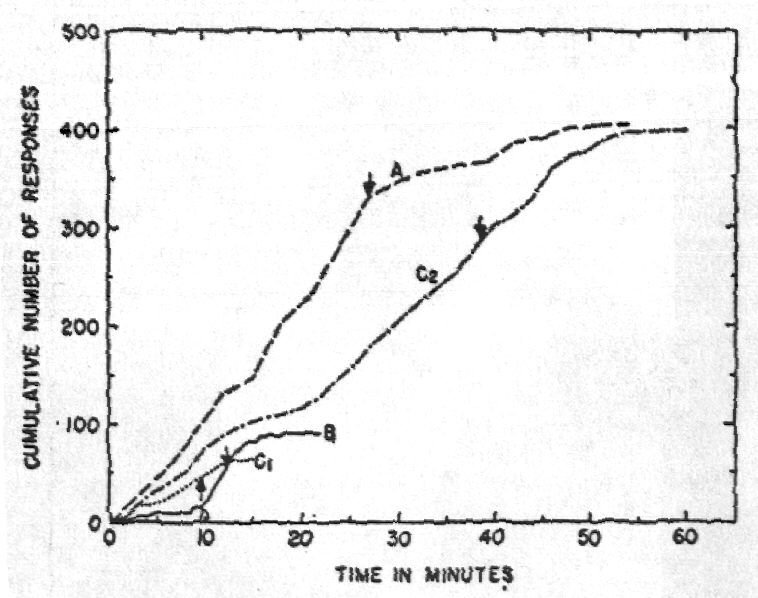

Fig. 3. Fixed Ratio Reinforcement

(A) R: slapping left knee SR: pencil tap, recoded by S. Two reinforcements worth 1 cent to S. At t =0, S is shifted from regular reinforcement to 15:1 rate of reinforcement. Extinction begins at arrow. Note bursts of high rates during extinction, followed by periods of complete inactivity.

Fig. 3. Fixed Ratio Reinforcement

(A) R: slapping left knee SR: pencil tap, recoded by S. Two reinforcements worth 1 cent to S. At t =0, S is shifted from regular reinforcement to 15:1 rate of reinforcement. Extinction begins at arrow. Note bursts of high rates during extinction, followed by periods of complete inactivity.

(B) and (C) (2 subjects). R: raising left forearm. SR: pencil tap, recorded by S. From t=0) to t = 9, regular reinforcement (approximation phase omitted). At arrow, shift to 3:1 ratio of reinforcement, yielding increase in rate. Approximation phase data: for subject B, 9 reinforcements over 2 minutes; for subject C, 17 reinforcements over 5 minutes.

Sometimes, an S, after giving a large number of responses under regular reinforcemnet, will show the symptoms of "satiation" (habituation?); that is, he will give negatively accelerated curves, declining to a rate of zero. Although reinforcements continue to be given, they become progressively less effective. If S "satiates," E should simply say, "Keep earning points." This almost always restores the rate to its value before decline.

Fig. 4. Interval Schedules

Fig. 4. Interval Schedules

(A) Variable interval (15 second average). R: Rub nose with right hand, SR: "good," recorded by S. Five "goods" worth 1 cent to S. At t = 0, interval schedule begins after 75 sec. of regular reinforcement. At arrow, extinction begins.

(B) Fixed interval (15 second). R: raise right forearm. SR: pencil tap, recorded by S. At t = 0, interval reinforcement begins. At arrow, extinction begins. Note that extinction is like that usually obtained following fixed ratio reinforcement.

(C) Variable interval (15 seconds). R: raise right forearem. SR: pencil tap, recorded by S. At t = 0, variable interval schedule begins. At arrow, extinction begins.

Schedules of reinforcement. The E is now free to follow any one of a number of schedules of reinforcement (3, 4), the simplest of which are fixed ratio (where every nth instance of a response is reinforced--Fig. 3) and fixed interval (where the first response occurring in each successive n-second interval following a reinforced response is reinforced--Fig 4). The behavior observed under these schedules corresponds closely with that observed in lower animals. As with lower animals, E will find it impossible to shift directly to a high ratio of reinforcement, or to a long fixed interval, without evidence of extinction. Fixed intervals of 15 seconds and fixed ratios up to 6:1 may be established immediately without danger of extinction. When S is shifted, he will at first show great increase in the number of kinds of behaviors he exhibits, even though the conditioned R continues to occur at the expected rate. Verbal behavior increases greatly, too. If S has been working at a steady rate under regular reinforcement (for simple behavior, usually 15 to 25 responses per minute) when shifted to a short fixed interval schedule, he may exhibit counting behavior and state that he is earning a point every, say, fifth response. If variable-interval or variable-ratio schedules are followed it is necessary for E to have prepared in advance a program, guiding him in determining which one of a series of responses he should reinforce (for variable ratio), or after how many seconds he should reinforce a response (for variable interval).

The results obtained are typical: High rates of response occur under ratio schedules, and so does rapid extinction when reinforcement is withdrawn. Low, but stable, rates follow the interval schedules, with large, smooth extinction curves. Temporal discrimination, verbalized or not, may occur on fixed interval schedules. An exception is found in those cases where S behaves, on fixed interval, as if he had been on a fixed ratio--he may give an extinction curve appropriate in form to fixed ratio reinforcement. The schedule has not "taken over."

Discrimination. After following a schedule of reinforcement for a time, E may proceed to set up a discrimination, extinguishing the response in the presence of one set of stimuli and continuing to reinforce it on schedule in the presence of another (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Discrimination Training

Fig. 5. Discrimination Training

(A) (B) R: Rub nose with right forefinger. SR: pencil tap, recorded by S. At t = 0, discrimination training begins, with SD and SD alternated through successive 30-second intervals and regular reinforcement in presence of SD. No reinforcement with SD. SD: E's cigarette rests in ash tray. SD: E's cigarette in his mouth. Curve A: responses under SD; Curve B: responses under SD.

(C) (D) R: turning single page of magazine. SR: pencil tap, recorded by S. At t = 0, regular reinforcement begins after approximation conditioning. At arrow, discrimination training begins, with SD and SD alternated through successive 60-second intervals, with regular reinforcement under SD, no reinforcement in presence of SD: desk lamp on; SD: desk lamp off. Curve C: responses under SD, Curve D: response under SD.

Here, it is advisable to have had S on a variable ratio or variable interval schedule, so that S's discrimination is not based solely on the omission of reinforcement. Discrimination in humans, as in rats, develops faster on ratio schedules.

For the rapid development of discriminations, it is desirable to choose as SD (negative discriminative stimulus) a fairly conspicuous event, such as E putting (and keeping) a cigarette in his mouth, or putting his recording pencil down, or placing a book on the table and leaving it there, or crossing his legs. The use of less conspicuous SD leads to the slow formation of the discrimination. Again, the data obtained are not readily distinguishable from the data obtained on rats (5), except that the time scale is shorter; that is, the process is more rapid.

"Learning set" data may be obtained in an hour or so by repeatedly reversing a discrimination: The discrimination process occurs more and more rapidly with successive reversals.

Chaining. After having had S on a schedule of reinforcement, E may decide to chain two responses. He does this by conditioning the first (A) and then extinguishing it, simultaneously conditioning the second (B). When the second is conditioned, he will then proceed to withhold reinforcement until the first recurs. He may now make reinforcement contingent on the occurrence of the sequence A-B, and so on. The Es have succeeded in chaining together several responses by this procedure. Learning sets for chaining also occur in human beings; during the extinction of a simple operant, an S who had been conditioned to chain a series of responses and had then been extinguished regressed to these old responses and gave them in new sequences with each other, and with the response undergoing extinction.

Extinction. During extinction, E should be careful to show minimal changes in manner and behavior other than those necessitated by the failure to reinforce. By thoughtlessly putting down his recording pencil, E may obtain a very small extinction curve. Extinction curves obtained do not differ in any remarkable way from comparable data obtained on the lower animals.

The human shows many interesting incidental pieces of behavior during extinction, whether or not he is aware--i.e., has verbalized--that no more reinforcements are forthcoming. He will make statements to the effect that he is losing interest, that he is bored, that he has a pressing engagement; he may "get mad," or make mildly insulting remarks, or he may suddenly decide that "this is a stupid game," or a "silly experiment." He may indulge in conversation full of remarks deprecating institutions (e.g., the college) or himself. One S said, "I'm going to give you one more minute to give me a point, and if you don't I'm going to go do math." (He left, in fact, after three minutes, when he had almost met the criterion of no responses in three minutes.) Many Ss volunteer the information that they "feel frustrated" when they can't get any more points.

The Ss also show behavior that some have called "regression," that is, they give ("fall back on") responses that were reinforced during approximation conditioning. Regression is most easily demonstrated if E first conditions one response and then extinguishes it while conditioning another. In this case, during the extinction of the second response conditioned, S will usually shift back and forth between the two.

Recording

The essential records are the number of responses that occur in unit time, and the specification of the responses that were reinforced. If E makes a check on a piece of lined paper whenever the conditioned response occurs, moves down one line at the end of successive 15-second recording intervals and puts a bar across the check whenever a reinforcing stimulus is delivered, he will have a record from which the familiar graph of cumulative number of responses as a function of time can be constructed.

Recording should be done behind a screen such as that provided by a clip-board or book held vertically. This recording procedure, together with the fact that E is busy watching S closely, has the merit that it is difficult for E to draw over-hasty conclusions about the "goodness" of the data that are being collected, so that badly intentioned student Es cannot manufacture "good" results. After learning to record with one hand, and to deliver reinforcements with the other, E will have no difficulty recording until S achieves very high rates of response, in which case, E may not be able to record or even count fast enough, and some responses will be missed. For experimental purposes, then, it is sometimes wise to choose a response for conditioning that requires not less than a second to complete.

The E may keep additional records such as, for example, a description of the responses reinforced during shaping, and of other behaviors that appear in extinction.

Awareness.4 Let us define "awareness" as the disposition of S to verbalize one or more of the rules followed by E. The S may be partially or completely "aware"; that is, he may be able to state one or more of these rules. He may be aware that a point is a reinforcing stimulus (as described in a textbook with which he is familiar); that E is trying to make him do something; that he is now doing something more often than he was before; that a certain response is being reinforced and is "right"; that he will get no points while E is smoking; that a point comes after every tenth response; that points average one per minute; that his response is being extinguished, and so on. He may be aware or unaware of any or of all of these.

Enough observations on such awareness have been made, both through the subject's emitted verbal behavior during the experiment, and by asking Ss about the experiment after its conclusion to permit some general statements:

1. In motor operant conditioning about half the subjects do not become aware of what response is conditioned, that is, of what they are doing that earns them points, until many reinforcements have been delivered and long after the stable rate of response has been achieved. These then remain for some time blissfully ignorant of what they are doing. Conditioning and extinction may take place without S ever "figuring it out."

2. Very few subjects become aware of the particular schedule they are being reinforced on for many minutes. On fixed interval schedules some Ss show the beginning of a temporal discrimination long before verbalizing it, and others may verbalize the interval and only later show a corresponding gradual change in behavior.

3. Many subjects, particularly those whose motor behavior is being reinforced, keep up a running verbal commentary on the procedure and exhibit very elaborate "reasoning" behavior. Their behavior is not different from that of silent Ss, or of Ss who show a less "rational" approach to the situation.

4. Subjects will occasionally show insight or "aha!" behavior; i.e., suddenly state that now they know what gives them points. Others become aware gradually: "I think it has something to do with my chin." Some are never quite sure: "Look, what was right?"

5. Most important, with some exceptions that will be described, awareness seldom seems to alter the behavior. Sudden "insights," when they occur, are not necessarily associated with abrupt changes in rate; abrupt changes in rate, e.g., "one-trial conditioning," may occur without such awareness. Statements such as, "Oh, now you're extinguishing me," made by highly sophisticated Ss are not correlated with abrupt and permanent declines of rate to zero--S ("on the chance that I'm wrong, or that you'll change the procedure") proceeds to generate the remainder of a typical extinction curve.

6. In experiments where S is, by instruction, fully aware of the experimental contingencies (but where he does not know the kind of results he is "supposed" to give ) he will behave immediately, on each instruction, as other Ss do only after long periods of reinforcement. He will immediately give, for example, a high rate of response when he is placed on fixed ratio; he will give only one or two responses under SD, or in extinction, and so on. He has "learning sets," or, to put it another way, the instructions behave like well-established discriminative stimuli. He starts with the behavior that is asymptotic for uninstructed Ss.

In any event, the associated verbal behavior, whether or not it in any way "directs" motor behavior, is highly sensitive to the experimental variables. During approximation conditioning and extinction, it is apt to occur at a relatively high rate, and to be aggressive in content: "The procedure is silly," E is "wasting my time," and so on. Under regular reinforcement, and on schedules, after stable performance is achieved, S has rather different sorts of things to say. The S's verbal "approach" to the situation is invariably interesting, as are the discrepancies between his statements about his performance and the performance itself. Since our procedures typically terminate with extinction, most Ss finally term the experiment "silly," "childish," and "stupid," despite the fact that they have "voluntarily" been working very hard indeed to earn points.

Possible research uses of the method. This kind of experiment, in which verbal behavior can be treated as either a dependent or independent variable, will perhaps find its greatest usefulness in the experimental analysis of so-called "cognitive processes"--that is, of S's awareness of what he is doing, and of the rather different dependencies of verbal and of other behaviors on a common set of experimental variables.

A second investigative area that this procedure makes amenable to experimental investigation is that of the classes of events that reinforce human behavior. What is a "point?" Why do "points" reinforce? How can their "value," i.e., their effectiveness in controlling behavior, be manipulated by instructions? Is a "point" from Experimenter A "worth as much" as one from Experimenter B? How will the addition of monetary reward vary the tendency of S to show satiation for "points"? What will showing S "group norms" for points collected do to his performance? It offers the possibility of measuring rapport.

A third area is one on which some preliminary investigations have been done: the gross changes in behavior that occur in extinction and in shifting from one reinforcement schedule to one giving fewer reinforcements. Many subjects become, under these conditions, "disturbed," "upset," "emotional," "aggressive" and "frustrated." Observations of changes in the rate of speaking, of moving about in a chair, and of such idiosyncratic operants as scratching the head, tapping the forehead, and so on, suggest that these rates are a function of the ratio of reinforced to unreinforced responses (6).

Discussion

Operant conditioning as it was described in The Behavior of Organisms is concerned with the behavior that the layman calls "voluntary." This characterization is still valid--the behavior during conditioning is not "forced," as one might characterize the conditioned knee-jerk, or necessarily "unconscious," as might be applied to the conditioned GSR. Ss work because they "want to." S's behavior is nonetheless lawful and orderly as a function of the manipulations of E, and his behavior is predictable by extrapolation from that of lower animals.

These assertions, like the procedure itself, involve no theoretical assumptions, presuppositions, or conclusions about "what is going on inside S's head." It does not assert that all learning occurs according to this set of laws, or that this process of conditioning is typical of all human learning. It does not assert that S is no better (or worse) than a rat, or that his behavior is unintelligent, or that since, say Ss get "information" from a reinforcing stimulus, so too do rats. The behavior is highly similar in the two cases--we leave it to others to make assertions to the effect that rats think like men, or that men think like rats.

The procedures can be characterized as bearing close relationship to a number of parlor games. Indeed, such conditioning might be considered by some as nothing more than a parlor game. This would not be the first time, however, that examples of rather basic psychological laws turned up in this context. Parlor games, like other recreational activities, are, to be sure, determined culturally, but it is doubtful that a parlor game could be found whose rules were in conflict with the general laws of behavior.

That the procedure is more than a parlor game is demonstrated by the fact that it provides a situation in which a number of the variables controlling voluntary behavior can be experimentally isolated and manipulated; that stable measures of a wide variety of behavior are yielded and, finally, that the procedure yields orderly data that may be treated in any one of a variety of theoretical systems.

Theoretical Discussion

The data lend themselves very well indeed to theoretical discussion in terms of "perceptual reorganization," "habit strength," "expectancy," or "knowledge of results," as well as to simple empirical description in the vocabulary of conditioning. Chàcun a son goût.

Summary

A series of procedures are presented that enable an experimenter to reproduce, using the motor (and verbal) behavior of human subjects, functions that have been previously described in the behavior of rats and pigeons. Some remarks on "awareness" in the situation are made.

Footnotes

1 The substance of this paper was presented to the Psychological Society, University College, University of London, in May, 1953. The writer wishes to express his thanks to the many students whose data were made available to him.

2 Compare with the Columbia Jester's rat, who remarks to a colleague at the bar of a Skinner Box, "Boy, have I got this guy conditioned: every time I press the bar, he gives me a pellet.

3 The graphs presented were selected to give typical, rather than "pretty" results. They were chosen from among more than 60 such records. The problem of selection was that of deciding which to omit, rather than which to include.

4 Since these experiments are most interesting when S is not aware of what behavior is being reinforced, we have followed the procedure of dividing laboratory sections into 2 group members of the other, and vice versa. One group is instructed to work on verbal behavior, and to bring it under discriminative control, and the other to work on motor behavior, and study extinction as a function of one or another schedule of reinforcement. The effect of the sets established is sufficient for many Ss, despite their otherwise full information on human conditioning, to remain unaware of what E is reinforcing, and what procedures he is following.

Incidentally, it is futile to tell an S who has been conditioned, or who is familiar with conditioning, that you want to "demonstrate conditioning," using him. Most Ss become very self-conscious under these circumstances and will not work. It is not at all difficult to demonstrate the procedure to a group that sits quietly and watches, but in this case it is necessary to use a naive S.

References

1. Greenspoon, J. The effect of verbal and non-verbal stimuli on the frequency of members of two verbal response classes. Unpublished doctor's dissertation, University of Indiana, 1950.

2. Sheffield, F. D., Roby, T. D., & Campbell, B. A. Drive reduction versus consummatory behavior as determinants of reinforcement. Journal of Comparative Physiological Psychology, 47, pp. 349-354, 1954.

3. Skinner, B. F. The Behavior of Organisms: An Experimental Analysis. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1938.

4. Skinner, B. F. Some contributions of an experimental analysis of behavior to psychology as a whole. American Psychologist, 8, pp. 69-78, 1953.

5. Smith, M. H., Jr., & Hoy, W. J. Rate of response during operant discrimination. Journal of experimental Psychology, 48, pp. 259-264, 1954.

6. Tugendhat, B. Changes in the overt behavior of human subjects in frustrating situations. Unpublished honors thesis, Radcliffe College, 1954.

Please address reprint requests, or any questions/comments, to: wverplan@utkux.utcc.utk.edu