Psychological Bulletin, 1989, Vol. 106, No. 1, 161-165

Copyright 1989 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 0033-2909/89/$00.75

Significance Tests and Deduction: Reply to Folger (1989)

Siu L. Chow

University of Regina, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada

Abstract Shows that agreeing with Folger's (1989) methodological observations does not mean that it is incorrect to use significance tests. This contention is based on the dynamics of theory corroboration, with reference to which the following distinctions are illustrated, namely, the distinctions between (a) statistical hypothesis testing, theory corroboration, and syllogistic argument, (b) a responsible experimenter and a cynical experimenter, (c) logical validity and methodological correctness, and (d) warranted assertability and truth.

I made a case in favor of using significance tests in theory-corroboration experimentation (Chow, 1988). Folger (1989) argued that it is incorrect to impose binary decisions when judging a theory because an experimental outcome may fail to match the theoretical expectations of an experiment as a result of an unsuccessful experimental manipulation. He further pointed out that "neither a theory's validity nor its invalidity is a matter of deductive certainty" (Folger, 1989, p. 155). An investigator would be led astray if the investigator did not appreciate the complications entailed in using modus tollens when the antecedent of the conditional proposition being used as the major premise was itself a conjunctive proposition.

I first recapitulate why using significance tests is appropriate in theory-corroboration experimentation. The dynamics of theory corroboration are then presented in order to achieve three interrelated objectives. They are (a) to make explicit certain distinctions that explain why Chow's (1988) argument is not incompatible with Folger's observations, (b) to identify the context in which Folger's observations are correct, and (c) to provide the framework for assessing the disagreement between Folger and Chow (1988).

Recapitulation of Chow's (1988) Argument

It is appropriate to use significance tests for the following reason. A syllogistic argument is implicated when an experiment is conducted for the explicit purpose of testing a theory. The syllogism itself consists of a major premise, a minor premise, and a conclusion as follows:

If A.I11, then X under EFG. (1)

D is dissimilar to X. (2a)

or

D is similar to X. (2b)

A.I11 is false. (3a)

or

A.I

11 is probably true. (3b)Propositions 3a and 3b are yoked to Propositions 2a and 2b, respectively, in the sense that Proposition 3a is the conclusion if Proposition 2a is chosen as the minor premise (viz., modus tollens) and that Proposition 3b is the conclusion if Proposition 2b is the minor premise.

As may be seen, the major premise of the argument of Premise 1 is a conditional statement whose antecedent is a conjunction of a set of auxiliary assumptions (viz., A) made by the experimenter and a particular implication of the theory of interest (viz., I). The consequent of Premise 1 is the theoretical expectation (commonly characterized as prediction) that should be true if the theory is true (Chow, 1987a).

The minor premise is supplied by the outcome of an experiment. Such an outcome either matches the theoretical expectation (viz., Premise 2b) or it does not (viz., Premise 2a). An experimenter requires a well-defined, objective decision rule to choose between these two mutually exclusive alternatives on the basis of the experimental outcome. This binary decision is well served by using significance tests. By virtue of modus tollens, the experimenter has to reject the theory if the experimental outcome does not match the theoretical expectation. The theory is deemed tenable if the experimental outcome matches the theoretical expectation.

Some commonly cited advantages of appealing to effect size were not real ones for two main reasons. First, it is still necessary to make a binary decision in choosing the minor premise of the syllogistic argument. The second reason is that a numerically larger effect size does not give more support to a theory than does a smaller effect size because (a) the tenability of a theory vis-à-vis the set of experimental data in question is determined by a syllogistic argument in toto and (b) logical validity is an all-or-none matter.

Dynamics of Theory Corroboration

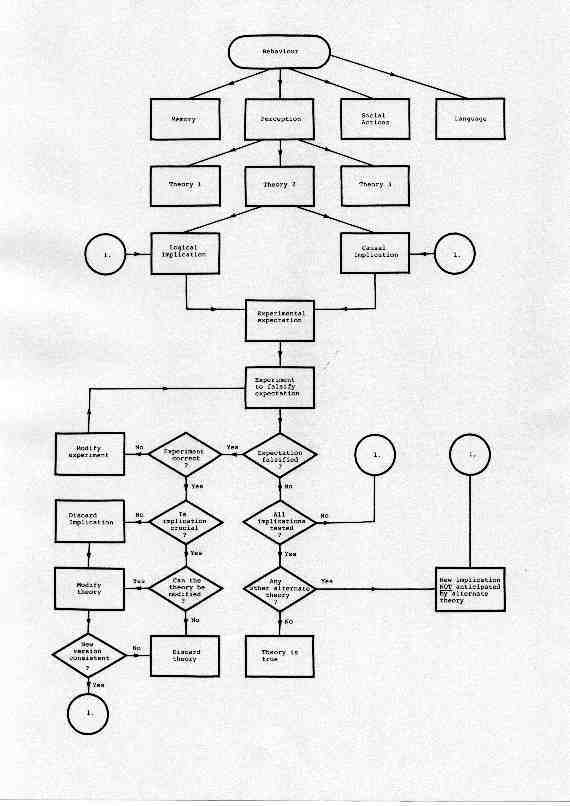

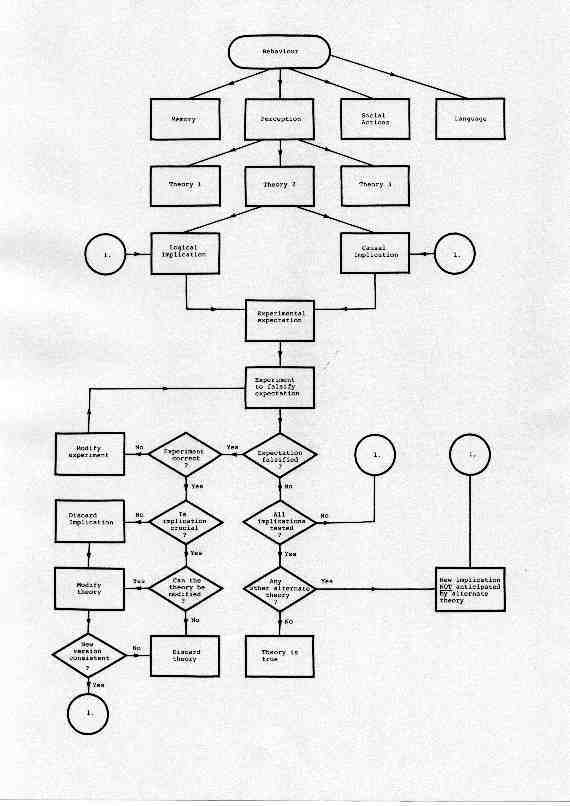

The dynamics of the theory-corroboration procedure depicted in Figure 1 (Chow, 1987b, p. 74, Figure 3-3) may be used to highlight some distinctions underlying the disagreement between Folger and Chow (1988). It depicts the logical steps implicated in establishing the truth of a theory (viz., Theory 2). The antecedent of Premise1 is determined collectively by the boxes labeled Theory 2, Logical Implication, and Causal Implication. The Experimental expectation box represents the consequent of Premise 1. The choice of Premise 2a or 2b as the minor premise is represented by the Expectation falsified? diamond.

The No route originating from the diamond is followed if the experimental outcome matches the theoretical expectation (i.e., Premise 2b is chosen as the minor premise). At the formal level, affirming the consequent of a conditional proposition does not lead to any definite conclusion about the antecedent of the conditional proposition. This is mimicked at the empirical level by the fact that the tenability of a theory cannot be established unambiguously because (a) the experimental outcome matches only one of its many implications (viz., the No arrow originating from the All implications tested? diamond) and (b) it is not possible to exhaust all contending theoretical alternatives with a single experiment (viz., the Yes arrow originating from the Any other alternate theory? diamond). The No arrow originating from the Any other alternate theory? diamond is only a logical possibility. It is appropriate to identify it here despite the fact that no one may ever be able to follow that arrow at the empirical level. The Yes route originating from the Expectation falsified? diamond is followed if the experimental outcome does not match the theoretical expectation (i.e., Premise 2a is chosen as the minor premise). To conclude that the theory is false (i.e., the Discard theory box) means that (a) the experiment has been properly conducted, (b) the theoretical implication represented by the experimental hypothesis is crucial to the theory, and (c) the theory cannot be modified. An experimenter who is serious about the theory being tested is obliged to make these assumptions.

Statistical Hypothesis Testing, Theory Corroboration, and Syllogism

A distinction has to be made between statistical hypothesis testing and theory corroboration. That the former is one among many other steps in the latter procedure may be readily seen from Figure 1. One complete loop of the sequence of steps originating from the Theory 2 box to any one of the nodes represented by a circle constitutes the theory-corroboration procedure. The issue of significance test or effect size is located at the Expectation falsified? diamond. Moreover, the Expectation falsified? diamond is involved every time the theory-corroboration procedure is carried out. Consequently, what can be said about one is not necessarily applicable to the other, even though both procedures are often characterized as hypothesis testing. For this reason, the fact that a binary decision is made at the level of the Expectation falsified? diamond (i.e., using significance tests) does not mean that the theory-corroboration procedure itself is binary in nature. By the same token, the fact that an experiment may fail for a multitude of reasons does not render the use of significance tests incorrect.

The syllogistic argument form mentioned earlier plays an important role in my argument. It is used to relate some components of the theory-corroboration procedure in a form that permits a decision on whether an experimental conclusion (the Discard theory or Theory is true box) is warranted by (a) what has been said about the theory (viz., the Logical Implication, Causal Implication, and Experimental expectation boxes) and (b) the outcome of an experiment (i.e., the Expectation falsified? box). That is, the syllogism itself is not the theory-corroboration procedure. Consequently, to say that logical validity is an all-or-none affair is not to say that the truth of a theory is, or can be, established by a binary decision. The all-or-none nature of the logical validity means that the outcome of an experiment either supports or does not support a theory (i.e., Manicas & Secord's, 1983, "warranted assertability").

Being Responsible Versus Being Cynical

Folger correctly pointed out that drawing Premise 3a as the conclusion on the basis of choosing Premise 2a as the minor premise (by modus tollens) means that the conjunction A.I11 is false. Because the truth-value of a conjunction depends on the truth-value of both of its two conjunct propositions, modus tollens does not guarantee that I11 is false. The set of auxiliary assumptions (i.e., A) may be false, not the implication of the theory of interest. Folger suggested that the rest of my argument is questionable because I did not appreciate this complication. There is, however, another way of looking at this issue.

Modus tollens does not prescribe that one has to be ignorant of, or indifferent to, the truth of both components of the conjunctive proposition when Premise 1 is the major premise. Folger seemed to have in mind someone who is ignorant of the subject matter of the experiment. At the same time, there is no excuse for an experimenter to plead ignorance regarding the truth of the set of auxiliary assumptions in the face of unexpected data. After all, the experimental expectation is partly based on the set of auxiliary assumptions. An experimenter is too cynical if his or her experimental expectation is based on something that he or she does not believe in. Alternatively, an experimenter is irresponsible if ignorance is used as an excuse for not rejecting the theory in the face of inconsistent data (see Meehl, 1978).

Cynicism and irresponsibility are minimized in practice by the fact that the choice of auxiliary assumptions is by no means arbitrary. The auxiliary assumptions come mainly from three sources, namely, (a) well-established theoretical ideas and empirical findings in the same or cognate areas, (b) methodological assumptions commonly held by other workers in the same area of study, and (c) the specificity of the theory from which the theoretical implication is derived. One of the criteria of a good theory is that it makes it difficult for an experimenter to use post hoc assumptions surreptitiously to explain away data that do not match the experimental expectation (Meehl, 1978; Turner, 1967).

In short, my treatment of modus tollens should not be misleading to a well-informed and responsible experimenter testing a good theory. This is the case because, under normal circumstances, a responsible experimenter must assume that the set of auxiliary assumptions made before the experiment is true. Consequently, the conjunction in the antecedent of Premise 1 should be treated as a categorical proposition by the experimenter. The fact that modus tollens may be misused does not detract from the logical validity of its all-or-none nature.

Logical Validity and Methodological Correctness

Another point that Folger made is that the outcome of an experiment may fail to support a tenable theory because the experimental manipulation itself is unsatisfactory. Hence, no definite conclusion about the theory can be drawn. This is true but not because modus tollens does not lead to a definite rejection of the antecedent of the conditional proposition that is its major premise. Rather, it is because neither Premise 2a nor Premise 2b can be accepted as a minor premise. There is no syllogism to speak of under such circumstances.

In the event that the experimenter has good reasons to question the auxiliary assumptions (not cynicism), he or she should admit that the experiment is incorrectly done. Moreover, the original experimental expectation has to be replaced in light of the new auxiliary assumptions. The only recourse is to discard the data collected and to conduct a proper experiment to test the new experimental expectation before anything can be said about the tenability of the theory. As may now be seen, this is no longer an issue of what modus tollens cannot do. It has become a question about the methodological correctness of the experiment.

Questions of this kind are more commonly known as questions about internal and external validity (Cook & Campbell, 1979). It is important to realize that validity in this context refers to correctness at the methodological level. It does not refer to a formal property. On the other hand, validity refers to correctness at the formal level when it is said that logical validity is all or none. In other words, it is possible to say that one cannot draw any experimental conclusion because of methodological incorrectness and that logical validity is all or none.

Warranted Assertability Versus Truth

It is important to emphasize that Figure 1 is a schematic representation of the theory-corroboration process. It is an overview of what is logically required in establishing the truth of a theory. It represents more than a single experiment. Furthermore, it is not restricted to the activities of a single investigator in chronological order. Many investigators may simultaneously investigate the same theory from different angles and with different intentions. More likely than not, two investigators may give opposite answers to some of the questions (e.g., the Experiment correct? box). Hence it is necessary to distinguish between whether a theory is tenable vis-à-vis a particular experiment and whether a theory is true. Going through the theory-corroboration loop once tells something about the former, and a syllogistic argument is used for that purpose. Establishing the truth of a theory involves continually reiterating the sequence of events depicted in Figure 1. Both deductive and inductive logic are used in every such reiteration (Chow, 1987b).

In other words, whether the answer to the Expectation falsified? diamond in Figure 1 is no or yes, the theory in question may be further challenged or corroborated. More specifically, along the No route originating from the Expectation falsified? diamond (i.e., the experimental outcome is consistent with the experimental expectation) are further implications and numerous other alternative explanations. It is for these reasons that converging operations are required (Garner, Hake, & Eriksen, 1956).

Although it is prudent for an experimenter to reject a theory if the answer to Expectation falsified? is yes, it does not mean that other experimenters would necessarily accept the experimenter's methodology or assumptions. His or her colleagues may have good reasons to test the theory with further experimentation because they entertain a different set of assumptions. For example, at about the time some investigators were documentating the sensory nature of iconic memory (e.g., Clark, 1969; Eriksen & Collins, 1967; Haber & Standing, 1969; Turvey & Kravetz, 1970; von Wright, 1968), other investigators were questioning the tenability of iconic memory by suggesting that Sperling's (1960) data may be explained in terms of some procedural artifacts (Dick, 1969; Holding, 1970, 1971, 1972; but see Coltheart, 1975, 1980).

In other words, I agree with Folger that whether a theory is true cannot be determined by deductive logic. My argument is that a properly constituted syllogism is required to determine whether a theory is justified vis-à-vis the outcome of a particular experiment. Given the distinction between warranted assertability and truth, it does not follow that I hold the "mistaken belief that modus tollens logic can provide deductive certainty about the validity of a theory" (Folger, 1989, p. 156). This misunderstanding may be avoided if a distinction is made between (a) the support a theory received from a particular experiment (viz., a complete loop from the Theory 2 box to any one of the circular nodes in Figure 1) and (b) its overall theoretical status (which is determined by how often it has withstood attempts to falsify it, how well it fares when compared to contending theories, how extensive the converging operations in its support are; i.e., the dynamics depicted in Figure 1 in toto).

Conclusion

In summary, I agree with many of Folger's statements. At the same time, the case in favor of using significance tests can still be made. Folger's reservations about my argument may be met when several distinctions are made, particularly with reference to the dynamics of theory corroboration.

References

Chow, S. L. (1987a). Science, ecological validity, and experimentation. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 17, 181-194.

Chow, S. L. (1987b). Experimental psychology: Rationale, procedures and issues. Calgary, Alberta, Canada: Detselig Enterprises.

Chow, S. L. (1988). Significance test or effect size? Psychological Bulletin, 103,105-110.

Clark, S. (1969). Retrieval of colour information from preperceptual memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 82, 263-266.

Coltheart, M. (1975). Iconic memory: A reply to Professor Holding. Memory & Cognition, 3, 42-48.

Coltheart, M. (1980). Iconic memory and visible persistence. Perception & Psychophysics, 27, 183-228.

Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (1979). Quasi-experimentation: Design and analysis issues for field studies. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Dick, A. 0. (1969). Relations between the sensory register and short-term storage in tachistoscopic recognition. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 82,279-284.

Eriksen, C. W., & Collins, J. F. (1967). Some temporal characteristics of visual pattern perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 74, 476-484.

Folger, R. (1989). Significance tests and the duplicity of binary decisions. Psychological Bulletin, 106, 155-160.

Garner, W. R., Hake, H. W., & Eriksen, C. W. (1956). Operationism and the concept of perception. Psychological Review, 63, 149-159.

Haber, R. N., & Standing, L. G. (1969). Direct measures of short-term visual storage. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 21, 43-54.

Holding, D. H. (1970). Guessing behaviour and the Sperling store. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 22, 248-256.

Holding, D. H. (I 97 1). The amount seen in brief exposures. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 23, 72-8 1.

Holding, D. H. (1972). Brief visual memory for English and Arabic letters. Psychonomic Science, 28, 241-242.

Manicas, P. T., & Secord, P. F. (1983). Implications for psychology of the new philosophy of science. American Psychologist, 38, 399-413.

Meehl, P. E. (1978). Theoretical risks and tabular asterisks: Sir Karl, Sir Ronald, and the slow progress of soft psychology. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 46, 806-834.

Sperling, G. (1960). The information available in brief visual presentations. Psychological Monographs, 74(11, Whole No. 498).

Turner, M. B. (1967). Psychology and the philosophy of science. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Turvey, M. T., & Kravetz, S. (1970). Retrieval from iconic memory with shape as the selection criterion. Perception & Psychophysics, 8, 171-172.

von Wright, J. M. (I 968). Selection in visual immediate memory. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 20, 62-68.

Received October 18, 1988

Accepted October 19, 1988

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Siu L. Chow, Department of Psychology, University of Regina, Regina, Saskatchewan S4S 0A2, CANADA.