The post Round Shields and Martial Practices of the Viking Age appeared first on Shipwrecks and Submerged Worlds.

]]>The post Round Shields and Martial Practices of the Viking Age appeared first on Shipwrecks and Submerged Worlds.

]]>The post New Member of Combat Archaeology: Claes B. Pettersson appeared first on Shipwrecks and Submerged Worlds.

]]>His bio can be found below and in the members section. Combat Archaeology has been in frequent contact with Claes and has had the pleasure of engaging in many informative discussions with him. Claes has recently written a small article on the Getaryggen 1567 battlefield project for Combat Archaeology which is currently in its final editorial stages – keep an eye open for this on our website!

Claes B. Pettersson

Claes B. Pettersson is an archaeologist, specialized in the Early Modern Period. He holds a BA in Historic Archaeology from the University of Lund, Sweden. Since 2004, he has been based at the Jönköping County Museum in Southern Sweden. His recent research has dealt with the conditions that made the rapid development of the Swedish state and its rise as a military power possible in the early 17th century. Excavations led by Claes includes both the Royal Manufactures (guns and cloth) and the castle, Jönköpings slott, in this once strategically important fortified town. Another project of his is the Getaryggen 1567 battlefield and the Danish campaign led by Daniel Rantzau. Here, excavations and extensive surveys have focused on Scandinavian warfare in the transition between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, its methods and consequences. Claes has published a wide range of articles based on his research and frequently participates in conferences and scientific networks focused on different aspects of conflict archaeology.

To learn more about Combat Archaeology Click Here.

The post New Member of Combat Archaeology: Claes B. Pettersson appeared first on Shipwrecks and Submerged Worlds.

]]>The post New Member of Combat Archaeology: Claes B. Pettersson appeared first on Shipwrecks and Submerged Worlds.

]]>His bio can be found below and in the members section. Combat Archaeology has been in frequent contact with Claes and has had the pleasure of engaging in many informative discussions with him. Claes has recently written a small article on the Getaryggen 1567 battlefield project for Combat Archaeology which is currently in its final editorial stages – keep an eye open for this on our website!

Claes B. Pettersson

Claes B. Pettersson is an archaeologist, specialized in the Early Modern Period. He holds a BA in Historic Archaeology from the University of Lund, Sweden. Since 2004, he has been based at the Jönköping County Museum in Southern Sweden. His recent research has dealt with the conditions that made the rapid development of the Swedish state and its rise as a military power possible in the early 17th century. Excavations led by Claes includes both the Royal Manufactures (guns and cloth) and the castle, Jönköpings slott, in this once strategically important fortified town. Another project of his is the Getaryggen 1567 battlefield and the Danish campaign led by Daniel Rantzau. Here, excavations and extensive surveys have focused on Scandinavian warfare in the transition between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, its methods and consequences. Claes has published a wide range of articles based on his research and frequently participates in conferences and scientific networks focused on different aspects of conflict archaeology.

To learn more about Combat Archaeology Click Here.

The post New Member of Combat Archaeology: Claes B. Pettersson appeared first on Shipwrecks and Submerged Worlds.

]]>The post New Member of Combat Archaeology: Claes B. Pettersson appeared first on Shipwrecks and Submerged Worlds.

]]>His bio can be found below and in the members section. Combat Archaeology has been in frequent contact with Claes and has had the pleasure of engaging in many informative discussions with him. Claes has recently written a small article on the Getaryggen 1567 battlefield project for Combat Archaeology which is currently in its final editorial stages – keep an eye open for this on our website!

Claes B. Pettersson

Claes B. Pettersson is an archaeologist, specialized in the Early Modern Period. He holds a BA in Historic Archaeology from the University of Lund, Sweden. Since 2004, he has been based at the Jönköping County Museum in Southern Sweden. His recent research has dealt with the conditions that made the rapid development of the Swedish state and its rise as a military power possible in the early 17th century. Excavations led by Claes includes both the Royal Manufactures (guns and cloth) and the castle, Jönköpings slott, in this once strategically important fortified town. Another project of his is the Getaryggen 1567 battlefield and the Danish campaign led by Daniel Rantzau. Here, excavations and extensive surveys have focused on Scandinavian warfare in the transition between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, its methods and consequences. Claes has published a wide range of articles based on his research and frequently participates in conferences and scientific networks focused on different aspects of conflict archaeology.

To learn more about Combat Archaeology Click Here.

The post New Member of Combat Archaeology: Claes B. Pettersson appeared first on Shipwrecks and Submerged Worlds.

]]>The post The Emergence of Naval Warfare: The Development of Boarding and Characteristics of Naval Battles appeared first on Shipwrecks and Submerged Worlds.

]]>Through ambushes and main force assaults, mankind has persisted in their violent conceits throughout history. Violent escapades rooted in rivalry and hatred have certainly added their share to the “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune.” For many, the taking up of arms entailed not only opposing a sea of troubles but also coming face to face with the sea itself. Naval warfare is both a fascinating and instructive genre; however, as part of an era when it is preferable to emphasize similarities of people rather than their differences, there is also certain unattractiveness of studying such violence today. But, as has become clear, such studies have much more to teach us than just that people can be violent to one another (Carman 2013: 177). Maritime archaeology, a discipline which preoccupies itself with investigations into humanity’s interaction with waterways, recognizes the significance of naval warfare studies, perhaps as an inherent consequence of the bellicose origins of much of the archaeological material. Although the discipline entails a lot more than sunken warships and cannons, it is certainly evident that much of the research has centered on subjects related to naval warfare. Far from being a narrow field, the research is fueled by a wide range of topics which have been made possible to investigate by the material left behind by the long history of humans causing havoc and mayhem on the seas. With the myriad of topics available within this genre and the fact that warfare has formed such a great part of our knowledge of the past – and, for some, been part of the present – it is not surprising that we have been left with the rather axiomatic notion that warfare has always been waged, both on land and at sea. However, is it possible to pinpoint any more precisely when humans began to bring large-scale combat out to sea? And what was the nature of the methods by which these early seaborne conflicts were carried out?

The Advent of Naval Warfare

The advent of naval warfare is challenging to pinpoint precisely in time and space. Given the ubiquitousness of warfare in both past and present, it is plausible to assume that the world’s oceans have been witness to large-scale violent encounters at least since the employment of watercraft sufficiently stable for hosting hand-to-hand combat scenarios or for the launching of missile attacks. Several finds from Egypt suggest that early naval warfare could have been conducted as early as the Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age. The oldest depiction of a boat that is more advanced in design than a canoe is a pictograph on a granite pebble found in the Khartoum Mesolithic layer (Usai & Salvatori 2007). The pictograph, however, is rather ambigious and does not allow for an interpretation of the stability of the watercraft in question. Being the only one of its kind, it is also quite the exception. The earliest convincing evidence of the emergence of more stable watercraft appear in the form of depictions on Amratian ceramics from c.3500 BC (McGrail 2001:17; fig. 1). Another important find is the ivory knife-handle from Gebel-el-Arak, dated to c. 3200 BC, on which two types of vessels are depicted in association with battle scenes (McGrail 2001:19; fig 2). However, due to iconographic ambiguity, the precise roles of the depicted vessels remain unclear. In consideration of the tendency for large-scale violence to intensify with increased political complexity and the dating of the aforementioned finds, it is interesting to note in this place – although not wholly surprising – that the development of more stable watercraft coincides with the emergence of nation states.

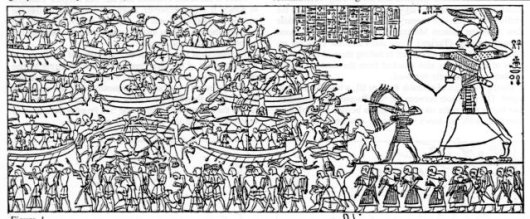

Notwithstanding these vindications, the first direct evidence of naval warfare comes in the form of documentary evidence from the Late Bronze Age. Contained in one of the few surviving documents which detail the reign of the last Hittite king, Suppiluliumas II, is a mentioning of a Hittite naval victory in 1210 BC (Gurney 1952: 31). The account simply states that the Hittites were victorious on the sea against an enemy based in Alasiya (modern day Cyprus), offering no further details about the exact identity of the enemy nor how victory was achieved. Despite these shortcomings, the document is commonly accepted as evidence of the first recorded naval battle in history. More information, however, is available about the second naval battle in recorded history, namely the Battle of the Delta which was fought between the Egyptians and the Sea Peoples in c. 1175 BC. Details from this battle are recorded on the reliefs of pharaoh Ramesses III’s mortuary temple at Medinet Habu in Luxor, Egypt. The reliefs contain, among other things, detailed battle scene depictions with boarding in which both shipborne archery and hand-to-hand combat forces are fully engaged in intense melee action. The apparent application of grappling hooks and ramming tactics in this battle reflect an advanced and well-established naval institution. Specialized naval technologies and tactics, then, seem to have been in use at least as early as the Late Bronze Age.

Boarding

Much of naval warfare in the past has revolved around boarding and measures to counter such actions and technology, i.e. anti-boarding. Within a combative context, boarding entails a forceful, non-consented entry aboard a ship. Fighting can occur in the process of entering the ship of the opposing force or aboard it. A successful boarding necessitates proper maneuvering towards the ship to be boarded, something which can be particularly difficult in harsh weather conditions. Another prequisite is that the ship of the opposing force is suppressed or that the crew is unaware of the entry. The ship must also be sufficiently stable for the boarding force to leap or climb onto the deck and, if necessary, sufficiently spacious to host a fight. For cultures in possession of such technology, but lacking or improficient in effective shipboard ordnance use, boarding was the primary method by which to conclude a battle at sea. However, boarding actions could also have been undertaken when it was desirable to seize a vessel without destroying it or when the objective was the removal of cargo or persons aboard the other vessel. The ship is a prize in itself but it can also carry valuable people or material, such as food, treasure, weaponry or information that may aid naval intelligence. Thus, while boarding lost some of its importance to navies after the advent of successful heavy ordnance fire, it remained an attractive enterprise, especially to pirates and privateers as well as to forces whose preferred method of attack was conducted under stealthy conditions.

Boarding was the primary means by which to achieve victory on the seas before the late 16th century by which time ordnance fire had been so effectively put to use by means of shipboard gun ports and gun carriages as well as broadside tactics that it had rendered boarding a secondary tactic. As such, naval hand-to-hand combat presents itself as an important aspect in investigations into warfare at sea.

Fig. 3: Relief from Medinet Habu, depicting the Battle of the Delta (adopted from Erman & Ranke 1923: 648; Cornelius 1987).

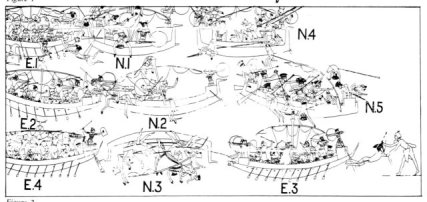

Fig. 4: Stages in the Battle of the Delta, as identified on the relief from Medinet Habu. E.1 and N.1 depict Egyptians throwing grappling hooks into sails and boarding the vessels of the Sea Peoples (adopted from Nelson 1943: 40-55, fig. 4; Cornelius 1987).

Space does not permit a full review of boarding in naval warfare here but the following should suffice as a general overview of its history and the main developments therein until the age of heavy ordnance fire. The details given here illustrate the veritable importance of hand-to-hand combat in naval warfare since the inception of sea battles and well into the Elizabethan period.

It is likely that the first naval battle in recorded history, the aforementioned battle of 1210 BC, was fought by means of boarding (Grant 2008). This can be inferred from its mere mentioning in the Hittite document, indicating that it was of sufficient scale to be considered noteworthy, and from the general tendency for any serious naval encounter at sea to be decisively concluded by means of hand-to-hand combat, at least before the development of heavy ordnance fire. However, as mentioned, the details of the Hittite victory in this battle are extremely brief and, admittedly, insufficient for such an argument to be made (Bryce 2007: 7; Gurney 1952: 31-32). Thus, although the battle of 1210 BC effectively marks the known beginning of naval warfare, boarding tactics can technically be said (at least with defensible reasons) to have been first employed in the second naval battle in recorded history, the Battle of the Delta in c. 1175 BC.

Fig. 5: The Athlit ram, found in 1980 off the coast of Israel near Atlit, is an example of an ancient ram used in battles such as that of Battle of Salamis. Carbon 14 dating of timber remnants date it to between 530 BC and 270 BC (Zemer 2015).

Although the general concept of boarding appears to have remained the same throughout the age of the galley, boarding tactics underwent several notable developments in the major periods of the classical and medieval world. While incendiary devices were occasionally used, the Greek and Persian tactics emphasized both boarding and ramming, and constructed ram-equipped warships which were successfully employed in the context of both smaller skirmishes and large-scale battles, e.g. in the Battle of Salamis (480 BC) (fig. 5). Later, the early Roman development of the corvus (a boarding ramp) proved to be advantageous in sea battles – such as in the Battle of Mylae (260 BC) – which allowed the renowned Roman land army to effectively engage in more or less regular terrestrial battle at sea. This, along with the harpax or harpago (a catapult-shot grapnel) brought focus back to boarding and away from ramming tactics (Dickie et al 2009: 55 ff.).

Fig. 6: Viking longships lashed together in anticipation of a naval battle as, for instance, was done in Battle of Nesjar (1016 AD) (adopted from Hjardar & Vike 2013: 86).

Fig. 7: Detail from the Madrid Skylitzes codex from the 12th century (Bibliteca Nacional de Madrid, Vitr. 26-2, Bild-Nr. 77, f 34 v. b.), showing Greek fire in use against the fleet of the rebel Thomas the Slav (adopted from Pászthory 1986: 31).

The desire of transforming a naval battle into one with properties more reminiscent of terrestrial battles appears to have been prevalent also in the medieval period. When fighting at sea, the Vikings occasionally lashed their ships together in order to provide a more stable platform for fighting and boarding (fig. 6; Hjardar & Vike 2013: 83-87). At this time, Greek fire, a new incendiary weapon, was also employed in naval warfare by Byzantium against the Arabs, and, according to Oddr Snorrason, even against the Vikings (fig. 7; Oddr Snorrason 2005: ch.5). The invention of this technology led to the production of a new warship, the siphonophore, making Byzantium less dependent on boarding than other contemporary powers, though it was still a common procedure (Dickie et al 2009: 56-60).

Fig. 8: Detail of Battle of Sluys from Jean Froissart’s Chronicles from the 14th century, contained in Bibliotheque Nationale MS Fr. 2643.

Another major development in warfare at sea was the emergence of ship types with high freeboards and elevated platforms from which archers could fire projectiles and repel attacks. On these ships, both fore and aft castles could be added for defense, making boarding an exceedingly difficult and dangerous undertaking. An early use of such a type in naval warfare was the cog. Though mentioned in literary works as early as the 9th century AD, the archaeological and historical evidence suggests that the cog was not fully integrated into naval warfare in the form of the floating fortress that gained a near hegemony over the northern seas until the 13th or 14th century (Hattendorff & Unger 2003: 41-43). The Norwegian Speculum Regale, written between AD 1240 and 1263, indicates an early Scandinavian use of martial cogs that had not only castles in the bow and stern but also crow nests in the mast top (ibid: 45). In England, the cog accounted for about 57% of the 1300 ships attested for military service during the years AD 1337-1360 (ibid: 43), proving itself as an effective engine of war in several major naval battles, including the Battle of Sluys in AD 1340 (fig. 8; Dickie et al. 2009: 64-70). Other successful developments within naval warfare- such as the carrack – were later built with the same considerations in mind. The carrack, of which Mary Rose (AD 1545) is an example, developed in the 15th century and was considerably more stable and spacious than the cog. The Battle of Lepanto (AD 1571) may be considered the climax of the chapter on naval warfare which emphasized boarding tactics. The galleys in this battle carried up to 400 men. The 400 galleys fighting at Lepanto may therefore have carried in total some 160, 000 men, making it the largest battle fought in 16th century Europe (Parker 1988: 89).

While naval technologies, tactics and strategies have been in perpetually development from the inception of naval warfare, there can be no doubt that the increased employment of naval artillery in the 15th and 16th centuries had an unrivalled impact on the nature of naval warfare, demanding considerable and constant adjustments to the new challenges faced by the evermore effective ordnance fire. These truly revolutionary steps greatly influenced the methods by which naval warfare was conducted, particularly with regards to the boarding traditions of the preceding ages.

From Battles to Sea Battles: the Phenomena and their Characteristics

Being a cultural choice, there is nothing that compels us to wage warfare in a specific way. There are many forms of institutionalized combat and violent means of achieving political goals. All forms of warfare, although often purely pragmatic in appearance, are inextricably bound up with cultural discourse and thus also a wide array of ideological assumptions and social considerations that guide warfare. However, while cultural discourse influence the conduct of warfare, it is also evident that certain external circumstances – such as the environment and availability of resources – has the potential to either encourage or facilitate certain actions and to restrict, or otherwise discourage, others.

To reach a more developed understanding of the phenomenon of naval warfare and the conditions by which sea battles operate, it is first necessary to place it within the wider context of warfare and battles in general. Naval warfare is not a unanimous phenomenon and expresses itself in variegated ways, each of which is characterized by a set of distinctive properties. In fact, warfare in general can take many different appearances, such as sieges, guerilla warfare, terrorism, battles etc. At their base, however, all forms of warfare, whether manifested in terrestrial, maritime or aerial form, are what can be termed “instrumental violence”, standing in contrast to “impulsive violence.” (James 2013:203). While impulsive violence is chiefly guided by emotions – such as rage, where a rational course of action is impossible – instrumental violence is more dependent upon the cognitive processes of the agent and has much less to do with emotional aggression (Panksepp & Biven 2012: 161). Instrumental violence entails highly calculative courses of action which are undertaken for the purpose of some gain. The rational and critical resources have been deployed in order to calculate the net benefit and weigh it against the risks involved in such undertakings, not least the consequences of passive action. It is, as Clausewitz eloquently described the nature of war, “Politics by other means” (Clausewitz 1832: book one, chapter 1, section 24). The demands of warfare, moreover, incline the belligerents to manipulate and control physical elements contained within the combative scenario for the purpose of gaining some advantage. Such undertakings likewise reflect, in varying degrees, a high cognitive ability in as far as this not only entails knowledge of each of the tactical elements but also of the underlying principles that govern the proceedings and various stages of warfare. The successful application of knowledge in a hectic milieu – such as that produced by combat and warfare – is challenging, to say the least. Rather paradoxically, then, the propagation of the ultimate chaos of human affairs, warfare, expresses itself in history conjointly with an attempt of introducing order into chaos.

The distinctive properties of battles, being an extreme case of instrumental violence, are especially interesting in relation to naval warfare. Battles are said to be “one of the most organized, premeditated, regimented and patterned forms of human behavior” (Staniforth et al 2014: 79, author’s emphasis). However, what distinguishes battles from virtually all other forms of warfare is the desire or willingness to meet on a battlefield for a single, massive clash between armed men for the purpose of mass killing, perhaps, but not necessarily, with some other ultimate end in mind. What is wanted is the completion of a mission goal through a coordinated main force assault which is to be undertaken by a large number of cooperative individuals.

In view of the characteristics of battles outlined above, it is not surprising that a great deal of naval warfare in the past – at least before age of heavy ordnance fire – has taken the form of sea battles. There are several consequences of employing fighting platforms at the sea. Most importantly, the appertaining environmental conditions of naval warfare are particularly influential in relation to the way warfare is conducted at sea. It is well-known that seafaring is in itself a hazardous undertaking. The belligerents are already in danger before the commencement of any battle; thus, the warship, although a powerful technology, can also be understood as a rather fragile sanctuary. These floating and mobile battlefields, essentially consisting of structured assemblages of floating wood, separate the crew from imminent danger but are vulnerable to external conditions, wherefore the significance of gales, waves and fire are also amplified in the case of naval warfare. In view of this, although a ship may be assisted or accompanied by other ships, it can generally be considered an isolated unit which is severely lacking in friendly entry and exit routes. This has often been carefully exploited by the enemy, not least by friendly forces, as illustrated by Alonso de Contreras’ (1582-1641) vivid account from the early 17th century:

“Our Captain then applied a refined stratagem: he allowed only a few people on deck, and had all the hatches carefully fastened down, so that people either had to fight or jump into the sea. It was a bloody confrontation.”

(Kirsch 1990: 67, quoting de Contreras 1961: 84-86).

As a result, naval warfare is rather reminiscent of island warfare, characterized by a limited amount of resources and a spatially confined combative arena. These circumstances, moreover, incline hand-to-hand combat aboard ships to be extremely intense since it is difficult to disengage from the fight and little chance of escape. The fighting forces are, quite literally, in the same boat. Hand-to-hand combat naval battles – as opposed to skirmishes, firefights and other smaller engagements –can thus be conceived as a form of fighting that is an inherent consequence of the aforementioned maritime conditions. Battles have long been considered to be an inherited legacy from the ancient Greek hoplites (Hanson 2009) or as a practice that begins with the Battle of Megiddo (1469 BC) (Carman 2009: 40). But, given the above, it may be necessary to look for the origins of battles on different grounds, perchance on no grounds at all but on the seas. At the very least, it would be neglectful not to acknowledge the significance of naval warfare in the context of the emergence of battles and its role in the development of warfare in general.

Conclusion

As witnessed, this enquiry into the emergence of naval warfare is composed of several different facets, each of which have varying connections with the subject and which have the potential to address the issue from several historical-archaeological and anthropological viewpoints. Despite the multifarious methods by which to approach the subject, the emergence of naval warfare remains a challenging topic to investigate, preeminently as a result of the lack of written sources and ambiguous lines of evidence. A certain level of unclarity surrounds even some of the most fundamental questions concerning the early beginnings of naval warfare. The earliest convincing evidence of naval battles, as a distinct method of waging war, comes from the Late Bronze Age. It is worth noting, however, that the early construction of stable watercraft coupled with the tendency of bellicose use of technology suggests an earlier date for naval warfare phenomena. These early seaborne conflicts, moreover, appear to have been conducted by way of boarding and anti-boarding tactics, this being the primary way of waging naval warfare until the 16th century. Admittedly, the tactical and technological developments treated in the course of these pages do not offer a full picture of the subject; they do, nonetheless, illustrate how many of these were specifically directed towards achieving victory on the seas in the form of battles. In examining the characteristics of battles and the inherent properties of naval warfare, it is apparent that many early seaborne conflicts have been fought out in the form of battles as a consequence of the maritime conditions. Far from being a definite work on the emergence of naval warfare and boarding, the pages presented here offer a general overview and introduction to the subject, and have served to bring out a number of new aspects and topics for archaeological and anthropological investigations. Naval warfare studies cover a broad range of interesting topics and it is easy to permit some of the most fundamental questions and issues sink into oblivion or complacency. Lest we forget, warfare has not always been waged on the seas nor is it a merely pragmatic phenomena arising from a social vacuum. Naval battles, although often purely functional in appearance, are inextricably bound up with cultural discourse and a wide range of ideological assumptions and social considerations that guide the ways of warfare.

References:

Bryce, T. 2007. Hittite Warrior. Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd.

Carman, J. 2009. Ancient Warfare. History Press Limited.

Carman, J. 2013. Past War and European Identity: Making Conflict Archaeology Useful. Ch. 9 in S. Ralph ((ed.), The Archaeology of Violence: Interdisciplinary Approaches: pp. 169-179. Albany: State University of New York Press.

von Clausewitz, C. 1976 [1832]. On War. Trans. and ed. by Michael Howard and Peter Paret. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

de Contreras, A. 1961. Trans, by Steiger Arnold. Das Leben des Capitán Alonso de Contreras von ihm Selbst erzählt. Zürich: Manesse Bibliothek der Weltliteratur.

Cornelius, I. 1987. The Battle of the Nile – Circa 1190 B.C. Military History Journal, 7(4). Available at: http://samilitaryhistory.org/vol074ic.html [Accessed: 13 Jan 2014].

Erman, A. & Ranke, H. 1923. Aegypten und aegyptisches Leben im Altertum. Mohr.

Dickie, I., Amber Books, Phyllis Jestice, Christer Jörgensen, Rob S. Rice, Martin J. Dougherty. 2009. Fighting Techniques of Naval Warfare: Strategy, Weapons, Commanders, and Ships: 1190 BC-Present, vol. 6. New York: Thomas Dunne Books.

Grant, R.G. 2008. Battle at Sea: 3,000 Years of Naval Warfare. DK Publishing.

Gurney, O.R. 1952. The Hittites. London: Penguin Books.

Hanson, V.D. 2009. The Western Way of War: Infantry Battle in Classical Greece. University of California Press.

Hattendorff, J. & Unger, R. (eds.). 2003. War at Sea in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Woodbridge and Rochester: Boydell Press.

Hjardar, Kim, and Vegard Vike. 2011. Vikinger i krig. Oslo: Spartacus.

James, S. 2013. Facing the Sword: Confronting the Realities of Martial Violence and Other Mayhem, Past and Present. Ch.5 in S. Ralph (ed.), The Archaeology of Violence: Interdisciplinary Approaches: pp. 98-115. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Kirsch, P. 1990. The Galleon: The Great Ships of the Armada Era. London: Conway Maritime Press Ltd.

McGrail, S. 2001. Boats of the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Panksepp, J. & Biven, L. 2012. The Archaeology of Mind: Neuroevolutionary Origins of Human

Emotions. New York & London: W.W. Norton & Company.

Parker, G. 1988. The Military Revolution: Military innovation and the rise of the West, 1500-1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pászthory, E. 1986. Über das ‘Griechische Feuer. Die Analyse eines spätantiken Waffensystems, Antike Welt 17 (2): 27–38.

Snorrason, O. 2005 [c.1190 ]. Translated by Peter Tunstall. The Saga of Olaf Tryggvason. Available at: http://www.oe.eclipse.co.uk/nom/Yngvar.html [Accessed: 23.08.2014].

Staniforth, M., Kimura, J. & Sasaki, R. 2014. Naval Battlefield Archaeology of the Lost Kublai Khan Fleets. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 43 (1): 76-86.

Usai, D. & Salvatori, S. 2007. The Oldest Representation of a Nile Boat. Antiquity, 81(314).

Zemer, A. 2015. The Athlit Ram. Haifa Museums. Available at: www.nmm.org.il/eng/Exhibitions/468/The_Athlit_Ram [Accessed: 02 Nov 2015].

To learn more about Combat Archaeology Click Here.

The post The Emergence of Naval Warfare: The Development of Boarding and Characteristics of Naval Battles appeared first on Shipwrecks and Submerged Worlds.

]]>The post The Emergence of Naval Warfare: The Development of Boarding and Characteristics of Naval Battles appeared first on Shipwrecks and Submerged Worlds.

]]>Through ambushes and main force assaults, mankind has persisted in their violent conceits throughout history. Violent escapades rooted in rivalry and hatred have certainly added their share to the “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune.” For many, the taking up of arms entailed not only opposing a sea of troubles but also coming face to face with the sea itself. Naval warfare is both a fascinating and instructive genre; however, as part of an era when it is preferable to emphasize similarities of people rather than their differences, there is also certain unattractiveness of studying such violence today. But, as has become clear, such studies have much more to teach us than just that people can be violent to one another (Carman 2013: 177). Maritime archaeology, a discipline which preoccupies itself with investigations into humanity’s interaction with waterways, recognizes the significance of naval warfare studies, perhaps as an inherent consequence of the bellicose origins of much of the archaeological material. Although the discipline entails a lot more than sunken warships and cannons, it is certainly evident that much of the research has centered on subjects related to naval warfare. Far from being a narrow field, the research is fueled by a wide range of topics which have been made possible to investigate by the material left behind by the long history of humans causing havoc and mayhem on the seas. With the myriad of topics available within this genre and the fact that warfare has formed such a great part of our knowledge of the past – and, for some, been part of the present – it is not surprising that we have been left with the rather axiomatic notion that warfare has always been waged, both on land and at sea. However, is it possible to pinpoint any more precisely when humans began to bring large-scale combat out to sea? And what was the nature of the methods by which these early seaborne conflicts were carried out?

The Advent of Naval Warfare

The advent of naval warfare is challenging to pinpoint precisely in time and space. Given the ubiquitousness of warfare in both past and present, it is plausible to assume that the world’s oceans have been witness to large-scale violent encounters at least since the employment of watercraft sufficiently stable for hosting hand-to-hand combat scenarios or for the launching of missile attacks. Several finds from Egypt suggest that early naval warfare could have been conducted as early as the Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age. The oldest depiction of a boat that is more advanced in design than a canoe is a pictograph on a granite pebble found in the Khartoum Mesolithic layer (Usai & Salvatori 2007). The pictograph, however, is rather ambigious and does not allow for an interpretation of the stability of the watercraft in question. Being the only one of its kind, it is also quite the exception. The earliest convincing evidence of the emergence of more stable watercraft appear in the form of depictions on Amratian ceramics from c.3500 BC (McGrail 2001:17; fig. 1). Another important find is the ivory knife-handle from Gebel-el-Arak, dated to c. 3200 BC, on which two types of vessels are depicted in association with battle scenes (McGrail 2001:19; fig 2). However, due to iconographic ambiguity, the precise roles of the depicted vessels remain unclear. In consideration of the tendency for large-scale violence to intensify with increased political complexity and the dating of the aforementioned finds, it is interesting to note in this place – although not wholly surprising – that the development of more stable watercraft coincides with the emergence of nation states.

Notwithstanding these vindications, the first direct evidence of naval warfare comes in the form of documentary evidence from the Late Bronze Age. Contained in one of the few surviving documents which detail the reign of the last Hittite king, Suppiluliumas II, is a mentioning of a Hittite naval victory in 1210 BC (Gurney 1952: 31). The account simply states that the Hittites were victorious on the sea against an enemy based in Alasiya (modern day Cyprus), offering no further details about the exact identity of the enemy nor how victory was achieved. Despite these shortcomings, the document is commonly accepted as evidence of the first recorded naval battle in history. More information, however, is available about the second naval battle in recorded history, namely the Battle of the Delta which was fought between the Egyptians and the Sea Peoples in c. 1175 BC. Details from this battle are recorded on the reliefs of pharaoh Ramesses III’s mortuary temple at Medinet Habu in Luxor, Egypt. The reliefs contain, among other things, detailed battle scene depictions with boarding in which both shipborne archery and hand-to-hand combat forces are fully engaged in intense melee action. The apparent application of grappling hooks and ramming tactics in this battle reflect an advanced and well-established naval institution. Specialized naval technologies and tactics, then, seem to have been in use at least as early as the Late Bronze Age.

Boarding

Much of naval warfare in the past has revolved around boarding and measures to counter such actions and technology, i.e. anti-boarding. Within a combative context, boarding entails a forceful, non-consented entry aboard a ship. Fighting can occur in the process of entering the ship of the opposing force or aboard it. A successful boarding necessitates proper maneuvering towards the ship to be boarded, something which can be particularly difficult in harsh weather conditions. Another prequisite is that the ship of the opposing force is suppressed or that the crew is unaware of the entry. The ship must also be sufficiently stable for the boarding force to leap or climb onto the deck and, if necessary, sufficiently spacious to host a fight. For cultures in possession of such technology, but lacking or improficient in effective shipboard ordnance use, boarding was the primary method by which to conclude a battle at sea. However, boarding actions could also have been undertaken when it was desirable to seize a vessel without destroying it or when the objective was the removal of cargo or persons aboard the other vessel. The ship is a prize in itself but it can also carry valuable people or material, such as food, treasure, weaponry or information that may aid naval intelligence. Thus, while boarding lost some of its importance to navies after the advent of successful heavy ordnance fire, it remained an attractive enterprise, especially to pirates and privateers as well as to forces whose preferred method of attack was conducted under stealthy conditions.

Boarding was the primary means by which to achieve victory on the seas before the late 16th century by which time ordnance fire had been so effectively put to use by means of shipboard gun ports and gun carriages as well as broadside tactics that it had rendered boarding a secondary tactic. As such, naval hand-to-hand combat presents itself as an important aspect in investigations into warfare at sea.

Fig. 3: Relief from Medinet Habu, depicting the Battle of the Delta (adopted from Erman & Ranke 1923: 648; Cornelius 1987).

Fig. 4: Stages in the Battle of the Delta, as identified on the relief from Medinet Habu. E.1 and N.1 depict Egyptians throwing grappling hooks into sails and boarding the vessels of the Sea Peoples (adopted from Nelson 1943: 40-55, fig. 4; Cornelius 1987).

Space does not permit a full review of boarding in naval warfare here but the following should suffice as a general overview of its history and the main developments therein until the age of heavy ordnance fire. The details given here illustrate the veritable importance of hand-to-hand combat in naval warfare since the inception of sea battles and well into the Elizabethan period.

It is likely that the first naval battle in recorded history, the aforementioned battle of 1210 BC, was fought by means of boarding (Grant 2008). This can be inferred from its mere mentioning in the Hittite document, indicating that it was of sufficient scale to be considered noteworthy, and from the general tendency for any serious naval encounter at sea to be decisively concluded by means of hand-to-hand combat, at least before the development of heavy ordnance fire. However, as mentioned, the details of the Hittite victory in this battle are extremely brief and, admittedly, insufficient for such an argument to be made (Bryce 2007: 7; Gurney 1952: 31-32). Thus, although the battle of 1210 BC effectively marks the known beginning of naval warfare, boarding tactics can technically be said (at least with defensible reasons) to have been first employed in the second naval battle in recorded history, the Battle of the Delta in c. 1175 BC.

Fig. 5: The Athlit ram, found in 1980 off the coast of Israel near Atlit, is an example of an ancient ram used in battles such as that of Battle of Salamis. Carbon 14 dating of timber remnants date it to between 530 BC and 270 BC (Zemer 2015).

Although the general concept of boarding appears to have remained the same throughout the age of the galley, boarding tactics underwent several notable developments in the major periods of the classical and medieval world. While incendiary devices were occasionally used, the Greek and Persian tactics emphasized both boarding and ramming, and constructed ram-equipped warships which were successfully employed in the context of both smaller skirmishes and large-scale battles, e.g. in the Battle of Salamis (480 BC) (fig. 5). Later, the early Roman development of the corvus (a boarding ramp) proved to be advantageous in sea battles – such as in the Battle of Mylae (260 BC) – which allowed the renowned Roman land army to effectively engage in more or less regular terrestrial battle at sea. This, along with the harpax or harpago (a catapult-shot grapnel) brought focus back to boarding and away from ramming tactics (Dickie et al 2009: 55 ff.).

Fig. 6: Viking longships lashed together in anticipation of a naval battle as, for instance, was done in Battle of Nesjar (1016 AD) (adopted from Hjardar & Vike 2013: 86).

Fig. 7: Detail from the Madrid Skylitzes codex from the 12th century (Bibliteca Nacional de Madrid, Vitr. 26-2, Bild-Nr. 77, f 34 v. b.), showing Greek fire in use against the fleet of the rebel Thomas the Slav (adopted from Pászthory 1986: 31).

The desire of transforming a naval battle into one with properties more reminiscent of terrestrial battles appears to have been prevalent also in the medieval period. When fighting at sea, the Vikings occasionally lashed their ships together in order to provide a more stable platform for fighting and boarding (fig. 6; Hjardar & Vike 2013: 83-87). At this time, Greek fire, a new incendiary weapon, was also employed in naval warfare by Byzantium against the Arabs, and, according to Oddr Snorrason, even against the Vikings (fig. 7; Oddr Snorrason 2005: ch.5). The invention of this technology led to the production of a new warship, the siphonophore, making Byzantium less dependent on boarding than other contemporary powers, though it was still a common procedure (Dickie et al 2009: 56-60).

Fig. 8: Detail of Battle of Sluys from Jean Froissart’s Chronicles from the 14th century, contained in Bibliotheque Nationale MS Fr. 2643.

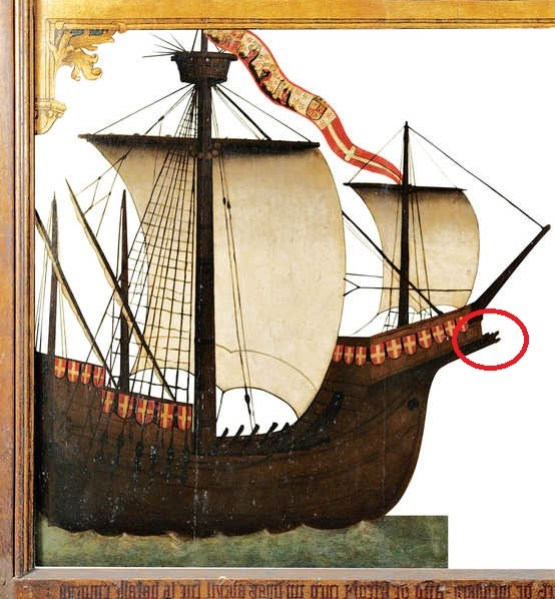

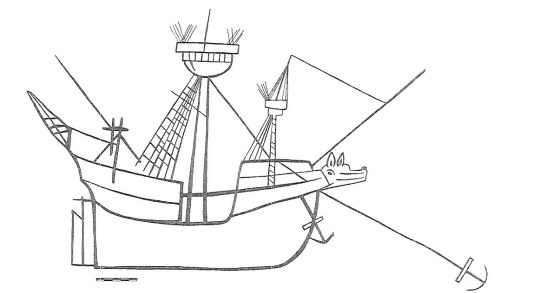

Another major development in warfare at sea was the emergence of ship types with high freeboards and elevated platforms from which archers could fire projectiles and repel attacks. On these ships, both fore and aft castles could be added for defense, making boarding an exceedingly difficult and dangerous undertaking. An early use of such a type in naval warfare was the cog. Though mentioned in literary works as early as the 9th century AD, the archaeological and historical evidence suggests that the cog was not fully integrated into naval warfare in the form of the floating fortress that gained a near hegemony over the northern seas until the 13th or 14th century (Hattendorff & Unger 2003: 41-43). The Norwegian Speculum Regale, written between AD 1240 and 1263, indicates an early Scandinavian use of martial cogs that had not only castles in the bow and stern but also crow nests in the mast top (ibid: 45). In England, the cog accounted for about 57% of the 1300 ships attested for military service during the years AD 1337-1360 (ibid: 43), proving itself as an effective engine of war in several major naval battles, including the Battle of Sluys in AD 1340 (fig. 8; Dickie et al. 2009: 64-70). Other successful developments within naval warfare- such as the carrack – were later built with the same considerations in mind. The carrack, of which Mary Rose (AD 1545) is an example, developed in the 15th century and was considerably more stable and spacious than the cog. The Battle of Lepanto (AD 1571) may be considered the climax of the chapter on naval warfare which emphasized boarding tactics. The galleys in this battle carried up to 400 men. The 400 galleys fighting at Lepanto may therefore have carried in total some 160, 000 men, making it the largest battle fought in 16th century Europe (Parker 1988: 89).

While naval technologies, tactics and strategies have been in perpetually development from the inception of naval warfare, there can be no doubt that the increased employment of naval artillery in the 15th and 16th centuries had an unrivalled impact on the nature of naval warfare, demanding considerable and constant adjustments to the new challenges faced by the evermore effective ordnance fire. These truly revolutionary steps greatly influenced the methods by which naval warfare was conducted, particularly with regards to the boarding traditions of the preceding ages.

From Battles to Sea Battles: the Phenomena and their Characteristics

Being a cultural choice, there is nothing that compels us to wage warfare in a specific way. There are many forms of institutionalized combat and violent means of achieving political goals. All forms of warfare, although often purely pragmatic in appearance, are inextricably bound up with cultural discourse and thus also a wide array of ideological assumptions and social considerations that guide warfare. However, while cultural discourse influence the conduct of warfare, it is also evident that certain external circumstances – such as the environment and availability of resources – has the potential to either encourage or facilitate certain actions and to restrict, or otherwise discourage, others.

To reach a more developed understanding of the phenomenon of naval warfare and the conditions by which sea battles operate, it is first necessary to place it within the wider context of warfare and battles in general. Naval warfare is not a unanimous phenomenon and expresses itself in variegated ways, each of which is characterized by a set of distinctive properties. In fact, warfare in general can take many different appearances, such as sieges, guerilla warfare, terrorism, battles etc. At their base, however, all forms of warfare, whether manifested in terrestrial, maritime or aerial form, are what can be termed “instrumental violence”, standing in contrast to “impulsive violence.” (James 2013:203). While impulsive violence is chiefly guided by emotions – such as rage, where a rational course of action is impossible – instrumental violence is more dependent upon the cognitive processes of the agent and has much less to do with emotional aggression (Panksepp & Biven 2012: 161). Instrumental violence entails highly calculative courses of action which are undertaken for the purpose of some gain. The rational and critical resources have been deployed in order to calculate the net benefit and weigh it against the risks involved in such undertakings, not least the consequences of passive action. It is, as Clausewitz eloquently described the nature of war, “Politics by other means” (Clausewitz 1832: book one, chapter 1, section 24). The demands of warfare, moreover, incline the belligerents to manipulate and control physical elements contained within the combative scenario for the purpose of gaining some advantage. Such undertakings likewise reflect, in varying degrees, a high cognitive ability in as far as this not only entails knowledge of each of the tactical elements but also of the underlying principles that govern the proceedings and various stages of warfare. The successful application of knowledge in a hectic milieu – such as that produced by combat and warfare – is challenging, to say the least. Rather paradoxically, then, the propagation of the ultimate chaos of human affairs, warfare, expresses itself in history conjointly with an attempt of introducing order into chaos.

The distinctive properties of battles, being an extreme case of instrumental violence, are especially interesting in relation to naval warfare. Battles are said to be “one of the most organized, premeditated, regimented and patterned forms of human behavior” (Staniforth et al 2014: 79, author’s emphasis). However, what distinguishes battles from virtually all other forms of warfare is the desire or willingness to meet on a battlefield for a single, massive clash between armed men for the purpose of mass killing, perhaps, but not necessarily, with some other ultimate end in mind. What is wanted is the completion of a mission goal through a coordinated main force assault which is to be undertaken by a large number of cooperative individuals.

In view of the characteristics of battles outlined above, it is not surprising that a great deal of naval warfare in the past – at least before age of heavy ordnance fire – has taken the form of sea battles. There are several consequences of employing fighting platforms at the sea. Most importantly, the appertaining environmental conditions of naval warfare are particularly influential in relation to the way warfare is conducted at sea. It is well-known that seafaring is in itself a hazardous undertaking. The belligerents are already in danger before the commencement of any battle; thus, the warship, although a powerful technology, can also be understood as a rather fragile sanctuary. These floating and mobile battlefields, essentially consisting of structured assemblages of floating wood, separate the crew from imminent danger but are vulnerable to external conditions, wherefore the significance of gales, waves and fire are also amplified in the case of naval warfare. In view of this, although a ship may be assisted or accompanied by other ships, it can generally be considered an isolated unit which is severely lacking in friendly entry and exit routes. This has often been carefully exploited by the enemy, not least by friendly forces, as illustrated by Alonso de Contreras’ (1582-1641) vivid account from the early 17th century:

“Our Captain then applied a refined stratagem: he allowed only a few people on deck, and had all the hatches carefully fastened down, so that people either had to fight or jump into the sea. It was a bloody confrontation.”

(Kirsch 1990: 67, quoting de Contreras 1961: 84-86).

As a result, naval warfare is rather reminiscent of island warfare, characterized by a limited amount of resources and a spatially confined combative arena. These circumstances, moreover, incline hand-to-hand combat aboard ships to be extremely intense since it is difficult to disengage from the fight and little chance of escape. The fighting forces are, quite literally, in the same boat. Hand-to-hand combat naval battles – as opposed to skirmishes, firefights and other smaller engagements –can thus be conceived as a form of fighting that is an inherent consequence of the aforementioned maritime conditions. Battles have long been considered to be an inherited legacy from the ancient Greek hoplites (Hanson 2009) or as a practice that begins with the Battle of Megiddo (1469 BC) (Carman 2009: 40). But, given the above, it may be necessary to look for the origins of battles on different grounds, perchance on no grounds at all but on the seas. At the very least, it would be neglectful not to acknowledge the significance of naval warfare in the context of the emergence of battles and its role in the development of warfare in general.

Conclusion

As witnessed, this enquiry into the emergence of naval warfare is composed of several different facets, each of which have varying connections with the subject and which have the potential to address the issue from several historical-archaeological and anthropological viewpoints. Despite the multifarious methods by which to approach the subject, the emergence of naval warfare remains a challenging topic to investigate, preeminently as a result of the lack of written sources and ambiguous lines of evidence. A certain level of unclarity surrounds even some of the most fundamental questions concerning the early beginnings of naval warfare. The earliest convincing evidence of naval battles, as a distinct method of waging war, comes from the Late Bronze Age. It is worth noting, however, that the early construction of stable watercraft coupled with the tendency of bellicose use of technology suggests an earlier date for naval warfare phenomena. These early seaborne conflicts, moreover, appear to have been conducted by way of boarding and anti-boarding tactics, this being the primary way of waging naval warfare until the 16th century. Admittedly, the tactical and technological developments treated in the course of these pages do not offer a full picture of the subject; they do, nonetheless, illustrate how many of these were specifically directed towards achieving victory on the seas in the form of battles. In examining the characteristics of battles and the inherent properties of naval warfare, it is apparent that many early seaborne conflicts have been fought out in the form of battles as a consequence of the maritime conditions. Far from being a definite work on the emergence of naval warfare and boarding, the pages presented here offer a general overview and introduction to the subject, and have served to bring out a number of new aspects and topics for archaeological and anthropological investigations. Naval warfare studies cover a broad range of interesting topics and it is easy to permit some of the most fundamental questions and issues sink into oblivion or complacency. Lest we forget, warfare has not always been waged on the seas nor is it a merely pragmatic phenomena arising from a social vacuum. Naval battles, although often purely functional in appearance, are inextricably bound up with cultural discourse and a wide range of ideological assumptions and social considerations that guide the ways of warfare.

References:

Bryce, T. 2007. Hittite Warrior. Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd.

Carman, J. 2009. Ancient Warfare. History Press Limited.

Carman, J. 2013. Past War and European Identity: Making Conflict Archaeology Useful. Ch. 9 in S. Ralph ((ed.), The Archaeology of Violence: Interdisciplinary Approaches: pp. 169-179. Albany: State University of New York Press.

von Clausewitz, C. 1976 [1832]. On War. Trans. and ed. by Michael Howard and Peter Paret. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

de Contreras, A. 1961. Trans, by Steiger Arnold. Das Leben des Capitán Alonso de Contreras von ihm Selbst erzählt. Zürich: Manesse Bibliothek der Weltliteratur.

Cornelius, I. 1987. The Battle of the Nile – Circa 1190 B.C. Military History Journal, 7(4). Available at: http://samilitaryhistory.org/vol074ic.html [Accessed: 13 Jan 2014].

Erman, A. & Ranke, H. 1923. Aegypten und aegyptisches Leben im Altertum. Mohr.

Dickie, I., Amber Books, Phyllis Jestice, Christer Jörgensen, Rob S. Rice, Martin J. Dougherty. 2009. Fighting Techniques of Naval Warfare: Strategy, Weapons, Commanders, and Ships: 1190 BC-Present, vol. 6. New York: Thomas Dunne Books.

Grant, R.G. 2008. Battle at Sea: 3,000 Years of Naval Warfare. DK Publishing.

Gurney, O.R. 1952. The Hittites. London: Penguin Books.

Hanson, V.D. 2009. The Western Way of War: Infantry Battle in Classical Greece. University of California Press.

Hattendorff, J. & Unger, R. (eds.). 2003. War at Sea in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Woodbridge and Rochester: Boydell Press.

Hjardar, Kim, and Vegard Vike. 2011. Vikinger i krig. Oslo: Spartacus.

James, S. 2013. Facing the Sword: Confronting the Realities of Martial Violence and Other Mayhem, Past and Present. Ch.5 in S. Ralph (ed.), The Archaeology of Violence: Interdisciplinary Approaches: pp. 98-115. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Kirsch, P. 1990. The Galleon: The Great Ships of the Armada Era. London: Conway Maritime Press Ltd.

McGrail, S. 2001. Boats of the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Panksepp, J. & Biven, L. 2012. The Archaeology of Mind: Neuroevolutionary Origins of Human

Emotions. New York & London: W.W. Norton & Company.

Parker, G. 1988. The Military Revolution: Military innovation and the rise of the West, 1500-1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pászthory, E. 1986. Über das ‘Griechische Feuer. Die Analyse eines spätantiken Waffensystems, Antike Welt 17 (2): 27–38.

Snorrason, O. 2005 [c.1190 ]. Translated by Peter Tunstall. The Saga of Olaf Tryggvason. Available at: http://www.oe.eclipse.co.uk/nom/Yngvar.html [Accessed: 23.08.2014].

Staniforth, M., Kimura, J. & Sasaki, R. 2014. Naval Battlefield Archaeology of the Lost Kublai Khan Fleets. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 43 (1): 76-86.

Usai, D. & Salvatori, S. 2007. The Oldest Representation of a Nile Boat. Antiquity, 81(314).

Zemer, A. 2015. The Athlit Ram. Haifa Museums. Available at: www.nmm.org.il/eng/Exhibitions/468/The_Athlit_Ram [Accessed: 02 Nov 2015].

To learn more about Combat Archaeology Click Here.

The post The Emergence of Naval Warfare: The Development of Boarding and Characteristics of Naval Battles appeared first on Shipwrecks and Submerged Worlds.

]]>The post The Emergence of Naval Warfare: The Development of Boarding and Characteristics of Naval Battles appeared first on Shipwrecks and Submerged Worlds.

]]>Through ambushes and main force assaults, mankind has persisted in their violent conceits throughout history. Violent escapades rooted in rivalry and hatred have certainly added their share to the “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune.” For many, the taking up of arms entailed not only opposing a sea of troubles but also coming face to face with the sea itself. Naval warfare is both a fascinating and instructive genre; however, as part of an era when it is preferable to emphasize similarities of people rather than their differences, there is also certain unattractiveness of studying such violence today. But, as has become clear, such studies have much more to teach us than just that people can be violent to one another (Carman 2013: 177). Maritime archaeology, a discipline which preoccupies itself with investigations into humanity’s interaction with waterways, recognizes the significance of naval warfare studies, perhaps as an inherent consequence of the bellicose origins of much of the archaeological material. Although the discipline entails a lot more than sunken warships and cannons, it is certainly evident that much of the research has centered on subjects related to naval warfare. Far from being a narrow field, the research is fueled by a wide range of topics which have been made possible to investigate by the material left behind by the long history of humans causing havoc and mayhem on the seas. With the myriad of topics available within this genre and the fact that warfare has formed such a great part of our knowledge of the past – and, for some, been part of the present – it is not surprising that we have been left with the rather axiomatic notion that warfare has always been waged, both on land and at sea. However, is it possible to pinpoint any more precisely when humans began to bring large-scale combat out to sea? And what was the nature of the methods by which these early seaborne conflicts were carried out?

The Advent of Naval Warfare

The advent of naval warfare is challenging to pinpoint precisely in time and space. Given the ubiquitousness of warfare in both past and present, it is plausible to assume that the world’s oceans have been witness to large-scale violent encounters at least since the employment of watercraft sufficiently stable for hosting hand-to-hand combat scenarios or for the launching of missile attacks. Several finds from Egypt suggest that early naval warfare could have been conducted as early as the Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age. The oldest depiction of a boat that is more advanced in design than a canoe is a pictograph on a granite pebble found in the Khartoum Mesolithic layer (Usai & Salvatori 2007). The pictograph, however, is rather ambigious and does not allow for an interpretation of the stability of the watercraft in question. Being the only one of its kind, it is also quite the exception. The earliest convincing evidence of the emergence of more stable watercraft appear in the form of depictions on Amratian ceramics from c.3500 BC (McGrail 2001:17; fig. 1). Another important find is the ivory knife-handle from Gebel-el-Arak, dated to c. 3200 BC, on which two types of vessels are depicted in association with battle scenes (McGrail 2001:19; fig 2). However, due to iconographic ambiguity, the precise roles of the depicted vessels remain unclear. In consideration of the tendency for large-scale violence to intensify with increased political complexity and the dating of the aforementioned finds, it is interesting to note in this place – although not wholly surprising – that the development of more stable watercraft coincides with the emergence of nation states.

Notwithstanding these vindications, the first direct evidence of naval warfare comes in the form of documentary evidence from the Late Bronze Age. Contained in one of the few surviving documents which detail the reign of the last Hittite king, Suppiluliumas II, is a mentioning of a Hittite naval victory in 1210 BC (Gurney 1952: 31). The account simply states that the Hittites were victorious on the sea against an enemy based in Alasiya (modern day Cyprus), offering no further details about the exact identity of the enemy nor how victory was achieved. Despite these shortcomings, the document is commonly accepted as evidence of the first recorded naval battle in history. More information, however, is available about the second naval battle in recorded history, namely the Battle of the Delta which was fought between the Egyptians and the Sea Peoples in c. 1175 BC. Details from this battle are recorded on the reliefs of pharaoh Ramesses III’s mortuary temple at Medinet Habu in Luxor, Egypt. The reliefs contain, among other things, detailed battle scene depictions with boarding in which both shipborne archery and hand-to-hand combat forces are fully engaged in intense melee action. The apparent application of grappling hooks and ramming tactics in this battle reflect an advanced and well-established naval institution. Specialized naval technologies and tactics, then, seem to have been in use at least as early as the Late Bronze Age.

Boarding

Much of naval warfare in the past has revolved around boarding and measures to counter such actions and technology, i.e. anti-boarding. Within a combative context, boarding entails a forceful, non-consented entry aboard a ship. Fighting can occur in the process of entering the ship of the opposing force or aboard it. A successful boarding necessitates proper maneuvering towards the ship to be boarded, something which can be particularly difficult in harsh weather conditions. Another prequisite is that the ship of the opposing force is suppressed or that the crew is unaware of the entry. The ship must also be sufficiently stable for the boarding force to leap or climb onto the deck and, if necessary, sufficiently spacious to host a fight. For cultures in possession of such technology, but lacking or improficient in effective shipboard ordnance use, boarding was the primary method by which to conclude a battle at sea. However, boarding actions could also have been undertaken when it was desirable to seize a vessel without destroying it or when the objective was the removal of cargo or persons aboard the other vessel. The ship is a prize in itself but it can also carry valuable people or material, such as food, treasure, weaponry or information that may aid naval intelligence. Thus, while boarding lost some of its importance to navies after the advent of successful heavy ordnance fire, it remained an attractive enterprise, especially to pirates and privateers as well as to forces whose preferred method of attack was conducted under stealthy conditions.

Boarding was the primary means by which to achieve victory on the seas before the late 16th century by which time ordnance fire had been so effectively put to use by means of shipboard gun ports and gun carriages as well as broadside tactics that it had rendered boarding a secondary tactic. As such, naval hand-to-hand combat presents itself as an important aspect in investigations into warfare at sea.

Fig. 3: Relief from Medinet Habu, depicting the Battle of the Delta (adopted from Erman & Ranke 1923: 648; Cornelius 1987).

Fig. 4: Stages in the Battle of the Delta, as identified on the relief from Medinet Habu. E.1 and N.1 depict Egyptians throwing grappling hooks into sails and boarding the vessels of the Sea Peoples (adopted from Nelson 1943: 40-55, fig. 4; Cornelius 1987).

Space does not permit a full review of boarding in naval warfare here but the following should suffice as a general overview of its history and the main developments therein until the age of heavy ordnance fire. The details given here illustrate the veritable importance of hand-to-hand combat in naval warfare since the inception of sea battles and well into the Elizabethan period.

It is likely that the first naval battle in recorded history, the aforementioned battle of 1210 BC, was fought by means of boarding (Grant 2008). This can be inferred from its mere mentioning in the Hittite document, indicating that it was of sufficient scale to be considered noteworthy, and from the general tendency for any serious naval encounter at sea to be decisively concluded by means of hand-to-hand combat, at least before the development of heavy ordnance fire. However, as mentioned, the details of the Hittite victory in this battle are extremely brief and, admittedly, insufficient for such an argument to be made (Bryce 2007: 7; Gurney 1952: 31-32). Thus, although the battle of 1210 BC effectively marks the known beginning of naval warfare, boarding tactics can technically be said (at least with defensible reasons) to have been first employed in the second naval battle in recorded history, the Battle of the Delta in c. 1175 BC.

Fig. 5: The Athlit ram, found in 1980 off the coast of Israel near Atlit, is an example of an ancient ram used in battles such as that of Battle of Salamis. Carbon 14 dating of timber remnants date it to between 530 BC and 270 BC (Zemer 2015).

Although the general concept of boarding appears to have remained the same throughout the age of the galley, boarding tactics underwent several notable developments in the major periods of the classical and medieval world. While incendiary devices were occasionally used, the Greek and Persian tactics emphasized both boarding and ramming, and constructed ram-equipped warships which were successfully employed in the context of both smaller skirmishes and large-scale battles, e.g. in the Battle of Salamis (480 BC) (fig. 5). Later, the early Roman development of the corvus (a boarding ramp) proved to be advantageous in sea battles – such as in the Battle of Mylae (260 BC) – which allowed the renowned Roman land army to effectively engage in more or less regular terrestrial battle at sea. This, along with the harpax or harpago (a catapult-shot grapnel) brought focus back to boarding and away from ramming tactics (Dickie et al 2009: 55 ff.).

Fig. 6: Viking longships lashed together in anticipation of a naval battle as, for instance, was done in Battle of Nesjar (1016 AD) (adopted from Hjardar & Vike 2013: 86).

Fig. 7: Detail from the Madrid Skylitzes codex from the 12th century (Bibliteca Nacional de Madrid, Vitr. 26-2, Bild-Nr. 77, f 34 v. b.), showing Greek fire in use against the fleet of the rebel Thomas the Slav (adopted from Pászthory 1986: 31).

The desire of transforming a naval battle into one with properties more reminiscent of terrestrial battles appears to have been prevalent also in the medieval period. When fighting at sea, the Vikings occasionally lashed their ships together in order to provide a more stable platform for fighting and boarding (fig. 6; Hjardar & Vike 2013: 83-87). At this time, Greek fire, a new incendiary weapon, was also employed in naval warfare by Byzantium against the Arabs, and, according to Oddr Snorrason, even against the Vikings (fig. 7; Oddr Snorrason 2005: ch.5). The invention of this technology led to the production of a new warship, the siphonophore, making Byzantium less dependent on boarding than other contemporary powers, though it was still a common procedure (Dickie et al 2009: 56-60).

Fig. 8: Detail of Battle of Sluys from Jean Froissart’s Chronicles from the 14th century, contained in Bibliotheque Nationale MS Fr. 2643.

Another major development in warfare at sea was the emergence of ship types with high freeboards and elevated platforms from which archers could fire projectiles and repel attacks. On these ships, both fore and aft castles could be added for defense, making boarding an exceedingly difficult and dangerous undertaking. An early use of such a type in naval warfare was the cog. Though mentioned in literary works as early as the 9th century AD, the archaeological and historical evidence suggests that the cog was not fully integrated into naval warfare in the form of the floating fortress that gained a near hegemony over the northern seas until the 13th or 14th century (Hattendorff & Unger 2003: 41-43). The Norwegian Speculum Regale, written between AD 1240 and 1263, indicates an early Scandinavian use of martial cogs that had not only castles in the bow and stern but also crow nests in the mast top (ibid: 45). In England, the cog accounted for about 57% of the 1300 ships attested for military service during the years AD 1337-1360 (ibid: 43), proving itself as an effective engine of war in several major naval battles, including the Battle of Sluys in AD 1340 (fig. 8; Dickie et al. 2009: 64-70). Other successful developments within naval warfare- such as the carrack – were later built with the same considerations in mind. The carrack, of which Mary Rose (AD 1545) is an example, developed in the 15th century and was considerably more stable and spacious than the cog. The Battle of Lepanto (AD 1571) may be considered the climax of the chapter on naval warfare which emphasized boarding tactics. The galleys in this battle carried up to 400 men. The 400 galleys fighting at Lepanto may therefore have carried in total some 160, 000 men, making it the largest battle fought in 16th century Europe (Parker 1988: 89).

While naval technologies, tactics and strategies have been in perpetually development from the inception of naval warfare, there can be no doubt that the increased employment of naval artillery in the 15th and 16th centuries had an unrivalled impact on the nature of naval warfare, demanding considerable and constant adjustments to the new challenges faced by the evermore effective ordnance fire. These truly revolutionary steps greatly influenced the methods by which naval warfare was conducted, particularly with regards to the boarding traditions of the preceding ages.

From Battles to Sea Battles: the Phenomena and their Characteristics

Being a cultural choice, there is nothing that compels us to wage warfare in a specific way. There are many forms of institutionalized combat and violent means of achieving political goals. All forms of warfare, although often purely pragmatic in appearance, are inextricably bound up with cultural discourse and thus also a wide array of ideological assumptions and social considerations that guide warfare. However, while cultural discourse influence the conduct of warfare, it is also evident that certain external circumstances – such as the environment and availability of resources – has the potential to either encourage or facilitate certain actions and to restrict, or otherwise discourage, others.

To reach a more developed understanding of the phenomenon of naval warfare and the conditions by which sea battles operate, it is first necessary to place it within the wider context of warfare and battles in general. Naval warfare is not a unanimous phenomenon and expresses itself in variegated ways, each of which is characterized by a set of distinctive properties. In fact, warfare in general can take many different appearances, such as sieges, guerilla warfare, terrorism, battles etc. At their base, however, all forms of warfare, whether manifested in terrestrial, maritime or aerial form, are what can be termed “instrumental violence”, standing in contrast to “impulsive violence.” (James 2013:203). While impulsive violence is chiefly guided by emotions – such as rage, where a rational course of action is impossible – instrumental violence is more dependent upon the cognitive processes of the agent and has much less to do with emotional aggression (Panksepp & Biven 2012: 161). Instrumental violence entails highly calculative courses of action which are undertaken for the purpose of some gain. The rational and critical resources have been deployed in order to calculate the net benefit and weigh it against the risks involved in such undertakings, not least the consequences of passive action. It is, as Clausewitz eloquently described the nature of war, “Politics by other means” (Clausewitz 1832: book one, chapter 1, section 24). The demands of warfare, moreover, incline the belligerents to manipulate and control physical elements contained within the combative scenario for the purpose of gaining some advantage. Such undertakings likewise reflect, in varying degrees, a high cognitive ability in as far as this not only entails knowledge of each of the tactical elements but also of the underlying principles that govern the proceedings and various stages of warfare. The successful application of knowledge in a hectic milieu – such as that produced by combat and warfare – is challenging, to say the least. Rather paradoxically, then, the propagation of the ultimate chaos of human affairs, warfare, expresses itself in history conjointly with an attempt of introducing order into chaos.

The distinctive properties of battles, being an extreme case of instrumental violence, are especially interesting in relation to naval warfare. Battles are said to be “one of the most organized, premeditated, regimented and patterned forms of human behavior” (Staniforth et al 2014: 79, author’s emphasis). However, what distinguishes battles from virtually all other forms of warfare is the desire or willingness to meet on a battlefield for a single, massive clash between armed men for the purpose of mass killing, perhaps, but not necessarily, with some other ultimate end in mind. What is wanted is the completion of a mission goal through a coordinated main force assault which is to be undertaken by a large number of cooperative individuals.

In view of the characteristics of battles outlined above, it is not surprising that a great deal of naval warfare in the past – at least before age of heavy ordnance fire – has taken the form of sea battles. There are several consequences of employing fighting platforms at the sea. Most importantly, the appertaining environmental conditions of naval warfare are particularly influential in relation to the way warfare is conducted at sea. It is well-known that seafaring is in itself a hazardous undertaking. The belligerents are already in danger before the commencement of any battle; thus, the warship, although a powerful technology, can also be understood as a rather fragile sanctuary. These floating and mobile battlefields, essentially consisting of structured assemblages of floating wood, separate the crew from imminent danger but are vulnerable to external conditions, wherefore the significance of gales, waves and fire are also amplified in the case of naval warfare. In view of this, although a ship may be assisted or accompanied by other ships, it can generally be considered an isolated unit which is severely lacking in friendly entry and exit routes. This has often been carefully exploited by the enemy, not least by friendly forces, as illustrated by Alonso de Contreras’ (1582-1641) vivid account from the early 17th century:

“Our Captain then applied a refined stratagem: he allowed only a few people on deck, and had all the hatches carefully fastened down, so that people either had to fight or jump into the sea. It was a bloody confrontation.”

(Kirsch 1990: 67, quoting de Contreras 1961: 84-86).

As a result, naval warfare is rather reminiscent of island warfare, characterized by a limited amount of resources and a spatially confined combative arena. These circumstances, moreover, incline hand-to-hand combat aboard ships to be extremely intense since it is difficult to disengage from the fight and little chance of escape. The fighting forces are, quite literally, in the same boat. Hand-to-hand combat naval battles – as opposed to skirmishes, firefights and other smaller engagements –can thus be conceived as a form of fighting that is an inherent consequence of the aforementioned maritime conditions. Battles have long been considered to be an inherited legacy from the ancient Greek hoplites (Hanson 2009) or as a practice that begins with the Battle of Megiddo (1469 BC) (Carman 2009: 40). But, given the above, it may be necessary to look for the origins of battles on different grounds, perchance on no grounds at all but on the seas. At the very least, it would be neglectful not to acknowledge the significance of naval warfare in the context of the emergence of battles and its role in the development of warfare in general.

Conclusion