Figure 2.1. Citebase search interface showing user-selectable criteria

for ranking results (with results appended for the search terms shown)

Open Citation Project, IAM Group,

Department of Electronics and Computer Science, University of Southampton,

SO17 1BJ, United Kingdom

Contact for correspondence: Steve Hitchcock sh94r@ecs.soton.ac.uk

Version history of this report

For a printable version of this paper, and for a version history and links to earlier and later versions, see this cover page

| "(Citebase) is a potentially critical component of the

scholarly information architecture"

Paul Ginsparg, founder of arXiv "I believe that ResearchIndex and Citebase are outstanding

examples (of compellingly useful tools). These tools still have to be perfected

to a point where their use is essential in any research activity. They

will have to become clearly more pleasant, more informative and more effective

than a visit to the library or the use of one's own knowledge of the literature.

Much, much more! And I, for one, believe that they are coming quite near

to this. But relatively few people realized this until now, even in these

more technology prone fields of study."

|

It has been noted that while Garfield’s basic intentions were "essentially bibliographic", he has conceded that "no one could have anticipated all the uses that have emerged from the development of the SCI" (Guedon 2001). One of these uses is co-citation analysis (Small 1973), which makes possible the identification of emerging trends, or 'research fronts', which today can be visualised using powerful computational techniques (Chen and Carr 1999).

Another use, however, was to divert the SCI into a new business as a career management tool. As a result, Guedon claims that in "introducing elitist components into the scientific quest for excellence, SCI partially subverted the meaning of the science game".

New Web-based citation indexing services, such as ResearchIndex (also known as CiteSeer; Lawrence et al. 1999) and Citebase from the Open Citation (OpCit) Project, are founded on the same basic principles elaborated by Garfield (1994). Unlike Web of Knowledge which indexes core journal titles, these new services index full-text papers that can be accessed freely by users on the Web, and the indexing services are also currently free. While it is possible that open access indexing services founded on open access texts could re-democratise the role of citation indexing, there is no doubt these services will offer qualitatively different services from those provided by ISI: "Newer and richer measures of 'impact' ... will be not only accessible but assessable continuously online by anyone who is interested, any time" (Harnad 2001). According to Lawrence (2001), open access increases impact.

An exemplary case for open access to scholarly communications has been outlined by Suber (2003), who earlier commented that the "greatest benefit" of open access content services that are free to users will be "to provide free online data to increasingly sophisticated software which will help scholars find what is relevant to their research, what is worthy, and what is new" Suber (2002). Citebase is an example of exactly that.

Despite the apparent advantage of open access, critical questions still have to be asked of these new services: are they useful and usable for the purposes of resource discovery and measuring impact? This report seeks to answer these questions based on an evaluation of Citebase, a citation-ranked search service. In the course of the investigation, some pointers to the resolution of these wider issues are also revealed.

Other services developed by the project, such as an application programming interface for reference linking, have been evaluated separately (Bergmark and Lagoze 2001). EPrints.org software for creating open access Web-based archives (Gutteridge 2002), receives feedback from its already extensive list of registered implementers, which informs continuing development of new versions of the software.

By discipline, approximately 200,000 of these papers are classified within arXiv physics archives. Thus, overwhelmingly, the current target user group for Citebase is physicists. The impact being made by the Open Archives Initiative (OAI; Van de Sompel and Lagoze 2002), which offers a technical framework for interoperability between digital archives, should help extend coverage significantly to other disciplines (Young 2002), through the emphasis of OAI on promoting institutional archives (Crow 2002). Hitchcock (2003) has monitored the growth of open access eprint archives, including OAI archives.

It is clear that a strong motivation for authors to deposit papers in institutional archives is the likelihood of subsequent inclusion in powerful resource discovery services which also have the ability to measure impact. For this reason there is a need to target this evaluation at prospective users, not just current users, so that Citebase can be designed for an expanding user base.

Citebase harvests OAI metadata records for papers, additionally extracting the references from each paper. The association between document records and references is the basis for a classical citation database. Citebase is sometimes referred to as “Google for the refereed literature”, because it ranks search results based on references to papers.

Citebase offers both a human user interface (http://citebase.eprints.org/), and an Open Archives (OAI)-based machine interface for further harvesting by other OAI services.

The primary Citebase Web user interface (Figure 2.1) shows how the user can classify the search query terms (typical of an advanced search interface) based on metadata in the harvested record (title, author, publication, date). In separate interfaces, users can search by archive identifier or by citation. What differentiates Citebase is that it also allows users to select the criterion for ranking results by Citebase processed data (citation impact, author impact) or based on terms in the records identified by the search, e.g. date (see drop-down list in Figure 2.1). It is also possible to rank results by the number of 'hits', a measure of the number of downloads and therefore a rough measure of the usage of a paper. This is an experimental feature to analyse both the quantitative and the temporal relationship between hit (i.e. usage) and citation data, as measures as well as predictors of impact. Hits are currently based on limited data from download frequencies at the UK arXiv mirror at Southampton only.

Figure 2.1. Citebase search interface showing user-selectable criteria

for ranking results (with results appended for the search terms shown)

The results shown in Figure 2.1 are ranked by citation impact: Maldacena's paper, the most-cited paper on string theory in arXiv at the time (September 2002), has been cited by 1576 other papers in arXiv. (This is the method and result for Q2.3 in the evaluation exercise described below.)

The combination of data from an OAI record for a selected paper with the references from and citations to that paper is also the basis of the Citebase record for the paper. A record can be opened from a results list by clicking on the title of the paper or on 'Abstract' (see Figure 2.1). The record will contain bibliographic metadata and an abstract for the paper, from the OAI record. This is supplemented with four characteristic services from Citebase:

Another option presented to users from a results list is to open a PDF version of the paper (see Figure 2.1). This option is also available from the record page for the paper. This version of the paper is enhanced with linked references to other papers identified to be within arXiv, and is produced by OpCit. Since the project began, arXiv has been producing reference linked versions of papers. Although the methods used for linking are similar, they are not identical and OpCit versions may differ from versions of the paper available from arXiv. An important finding of the evaluation is whether reference linking of full-text papers should be continued outside arXiv. An earlier, smaller-scale evaluation, based on a previous OpCit interface (Hitchcock et al. 2000), found that arXiv papers are the most appropriate place for reference links because users overwhelmingly use arXiv for accessing full texts of papers, and references contained within papers are used to discover new works.

The evaluation was performed over four months from June 2002, when the first observational tests took place, to the end of October 2002 when a closure notice was placed on the forms and the submit buttons were disabled.

The evaluation was managed by the OpCit project team in the IAM Group at Southampton University, the same team that reported on the evaluation of the forerunner eLib-funded Open Journal Project (Hitchcock et al. 1998). The arXiv Cornell partners in the project assisted with design and dissemination.

Observed tests of local users were followed by scheduled announcements to selected discussion lists for JISC and NSF DLI developers, OAI developers, open access advocates and international librarian groups. Finally, following consultation with our project partners at arXiv Cornell, arXiv users were directed to the evaluation by means of links placed in abstract pages for all but the latest papers deposited in arXiv.

After removing blanks, duplicates and test submissions, a total of 195 valid submissions of Form 1 were received. Of these users, 133 also completed Form 2, which was linked from the submit button of Form 1.

As already indicated, Citebase is aimed at a much wider user group, both now and in the future, and the evaluation had to be extended to a representative section of those users. Open invitation is one way of achieving this. There are drawbacks to inviting evaluation based on a Web-only questionnaire, most obviously the lack of direct contact with users, and the consequent loss of motivation and information. Balancing this should be simplicity, easy accessibility and continuous availability. Web surveys have widened use and reduced the costs of survey techniques, but introduce new complexities (Gunn 2002). Efforts were made to ensure the forms were usable, based on the observed tests, and that Citebase offered a reliable service during the period of the evaluation. Availability of forms and service were monitored and maintained during the period of evaluation.

A perennial problem with forms-based evaluation, whether users are remote or not, is that badly designed forms can become the object of the evaluation. In tests of this type, where most users are experiencing a service for the first time, observation suggests that users may have understood the service more intuitively had they just looked at it as a search service rather than being introduced to it via step-by-step questions. Citebase was promoted only minimally prior to the investigation. This raises the question of whether the service to be evaluated, Citebase, should have been promoted more extensively. This would have increased familiarity, but it was felt this would make it more difficult to attract users to the evaluation unless those users were being brought to Citebase via the evaluation.

In contrast to Web forms, usage logs are an impeccable record of what people actually do, although there are problems of interpretation, and there are no standards for the assessment of Web logs.

The response to the evaluation from arXiv physicists, the primary target user group, was a little below expectations, although replies from other users were higher than expected. An earlier survey of users of eprint archives received nearly 400 replies from arXiv users (Hunt 2001). It is likely the lower number of respondents to the evaluation was due to the method of linking from arXiv to the evaluation. For the earlier survey, arXiv linked directly from a notice on its home page to the Web form. In this case abstract pages for papers in arXiv linked to the corresponding Citebase records. To get users to the evaluation form required that a linked notice be inserted temporarily in the Citebase records (Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1 Adding a temporary notice to Citebase records to attract

arXiv users to participate in this survey

As a means of bringing arXiv users to Citebase on an ongoing basis, this is an ideal, task-coupled arrangement. From the perspective of the evaluation, however, users were expected to follow two links to reach the evaluation, and were thus required to take two steps away from their original task. Since there was no direct link to the evaluation from the arXiv home page, and therefore no prior advocacy for, or expectation of, Citebase or the evaluation, perhaps it should not be surprising that the response did not match the earlier survey.

Usage of Citebase would have been affected for the same reason; also by a prominent notice:

Citebase (trial service, includes impact analysis)

placed alongside the new links to Citebase in arXiv (Figure 1 in Hitchcock et al. 2002).

Since the evaluation the Citebase developer (Tim Brody) has worked with our arXiv partners to refine Citebase. The trial notices have been removed and in February 2003 Citebase became a full featured service of arXiv.

One area of concern for Citebase were the descriptions, support and help pages, a vital part of any new and complex service. There was some reorganisation of this material, and new pages were added. This is an ongoing process and will continue to be informed by users.

Terminology was another aspect raised leading up to the evaluation. Terms used in the evaluation form such as "most cited" can be interpreted as the largest number of citations for an author or the largest average number of citations per paper for the same author. On the form this was revised (Q2.1). More generally, efforts were made to make terminology in Citebase comparable with ISI.

If bibliographic tools have been subverted, whether by design or not, to serve as career management tools, there is no hiding from the fact that new, experimental services will produce contentious results. This was a particularly acute concern during the preparation of Citebase for testing. A warning notice was added prominently to the main search page:

| Citebase is currently only an experimental demonstration. Users are cautioned not to use it for academic evaluation yet. Citation coverage and analysis is incomplete and hit coverage and analysis is both incomplete and noisy. |

Citebase was incomplete during the evaluation because new arXiv papers and their references were not harvested once the evaluation began in June. It was decided the data should be static during the evaluation, to ensure all users were evaluating the same object (some minor changes were made during the evaluation period, and these are highlighted in section 4.1). In arXiv, papers with numbers before 0206001 (June) had a link to Citebase, but not those deposited after.

Also, not all references could be extracted from all papers, which clearly would affect the results of citation impact. Techniques and software for automated reference extraction have been discussed by Bergmark (2000). Since the evaluation closed Citebase data have been brought up-to-date, and the reference parsing algorithm has been refined to improve extraction rates. An open source version of this software is available as ParaTools (http://paracite.eprints.org/developers/downloads.html).

Warnings were also strengthened, after much discussion, around the 'hits' data graphs displayed in Citebase records (Figure 4.1). Reservations about this feature were expressed by arXiv Cornell colleagues, for the following reasons:

Figure 4.1. Citation/Hit History graph in a Citebase record, with

prominent Caution! notice

| Citebase changes/updates | Possible effect on evaluation (Form 1) |

|---|---|

| On Citebase search results page (Figure 2.1), add explicit 'Abstract/PDF' links to records (some users did not realise that clicking a title brings you to the abstract) | Q2.3 |

| New layout for internal links within Citebase record pages | Q2.4 |

| 'Linked PDF' label on Citebase record pages replaced by green 'PDF' graphic | Q2.6a (full-text download) |

| Hits/citations graphs now on a different scale, hits warning added | Q2.4-, Q3.1 |

Similarly, since Citebase will extend coverage to new OAI archives, it is helpful to know the level of awareness of OAI among evaluators (Q1.4) , and whether they use other OAI services (Q1.5).

As with all other sections on the evaluation forms, this section ends by inviting open comments from evaluators, which can be used to comment on any aspect of the evaluation up to this point.

At this point users were prompted to open a new Web browser window to view the main Citebase search interface. It was suggested this link could have been placed earlier and more prominently, but this was resisted as it would have distracted from the first section.

Questions 2.1-2.3 involved performing the same task and simply selecting a different ranking criterion from the drop-down list in the search interface (Figure 2.1). Selectable ranking criteria is not a feature offered by popular Web search engines, even in advanced search pages, which the main Citebase search page otherwise resembles. The user's response to the first question is therefore important in determining the method to be used, and Q2.1 might be expected to score lowest, with familiarity increasing for Q2.2 and Q2.3. Where Q2.1 proved initially tricky, observed tests revealed that users would return to Q2.1 and correct their answer. We have no way of knowing to what extent this happened in unobserved submissions, but allowance should be made for this when interpreting the results.

The next critical point occurs in Q2.4, when users are effectively asked for the first time to look below the search input form to the results listing for the most-cited paper on string theory in arXiv (Q2.3). To find the most highly cited paper that cites this paper, notwithstanding the apparent tautology of the question, users must recognise they have to open the Citebase record for the most-cited paper by clicking on its title or on the Abstract link. Within this record the user then has to identify the section 'Top 5 Articles Citing this Article'. To find the paper most often co-cited with the current paper (Q2.5) the user has to scroll down the page, or use the link, to find the section 'Top 5 Articles Co-cited with this Article'.

Now it gets slightly harder. The evaluator is asked to download a copy of the full-text of the current paper (Q2.6a). What the task seeks to determine is the user's preference for selecting either the arXiv version of the paper or the OpCit linked PDF version. Both are available from the Citebase record. A typical linked PDF was illustrated by Hitchcock et al. (2000). Originally the Citebase record offered a 'linked PDF', but during the evaluation the developer changed this to a PDF graphic (Table 4.1). The significance of omitting 'linked' is that this was the feature differentiating the OpCit version. Given that it is known physicists tend to download papers in Postscript format rather than PDF (http://opcit.eprints.org/ijh198/3.html), it is likely that a simple PDF link would have little to recommend it against the link to the arXiv version.

As a check on which version users had downloaded, they were asked to find a reference (Q2.6b) contained within the full text (and which at the time of the evaluation was not available in the Citebase record, although it appeared in the record subsequently). To complete the task users had to give the title of the referenced paper, but this is not as simple as it might be because the style of physics papers is not to give titles of papers in references. To find the title, the user would need to access a record of the referenced paper. Had they downloaded the linked version or not? If so, the answer was one click away. If not, the task was more complicated. As final confirmation of which version users had chosen, and how they had responded subsequently, users were asked if they had resorted to search to find the title of the referenced paper. In fact, a search using Citebase or arXiv would not have yielded the title easily.

In this practical exercise users were asked to demonstrate completion of each task by identifying an item of information from the resulting page, variously the author, title or URL of a paper. Responses to these questions were automatically classified as true, false or no response. Users could cut-and-paste this information, but to ensure false responses were not triggered by mis-keying or entering an incomplete answer, a fuzzy text matching procedure was used in the forms processor.

Although this is an indirect measure of task completion, the results of this exercise can be read as an objective measure showing whether Citebase is a usable service. As an extra aid to judge the efficiency with which the tasks are performed, users were asked to time this section. One idea was to build a Javascript clock into the form, but this would have required additional user inputs and added to the complexity of the form.

Questions 3.1 and 3.2 enquire about Citebase as it is now and as it might be, respectively. It is reasonable to limit choices in the idealised scenario (Q3.2) so that users have to prioritise desired features. Users are likely to be more critical of the actual service, so it seems safe to allow a more open choice of preferred features.

Citebase has to be shaped to offer users a service they cannot get elsewhere, or a better service. Q3.3 seeks to assess the competition. This part of the evaluation is concluded by asking the user for a view on Citebase, not in isolation, but in comparison with familiar bibliographic services.

There is a second part to the evaluation, which is displayed to users automatically on submission of Form 1. It became apparent from observed tests that users do not always wait for a response to the submission and may miss Form 2, so a clear warning was added above the submission button on Form 1.

On submission the results were stored in a MySQL database and passed to an Excel spreadsheet for analysis.

Form 1 prompted users to respond to specific questions and features, and gives an impression of their reaction to the evaluated service, but does not really explore their personal feelings about it. A recommended way of tackling this is an approach based on the well-known Software Usability Measurement Inventory (SUMI) form of questionnaire for measuring software quality from the end user's point of view. Form 2 is a short implementation of this approach which seeks to discover:

Four response options, ranging from very positive to very negative, are offered for each of four statements in each section. These responses are scored 2 to -2. A neutral response is not offered, but no response scores zero. A statement that users typically puzzle over is 'If the system stopped working it was not easy to restart it', before choosing not to respond if the system did not fail at any stage. Users often query this, but an evaluation, especially where users are remote from testers, has to anticipate all possible outcomes rather than make assumptions about reliability.

Scenario: Users worked with machines in their own environment. Users were assured it was not they who were being tested; the system was being tested. Once they were in front of a machine with a working Web browser and connection, they were handed a printed copy of the evaluation forms as an aid and for notes, not instead of the online version. They were then given the URL to access evaluation Form 1, with no other instruction. Once started, observers were to avoid communication with users. Users were debriefed after completing the tasks.

Main findings (actions):

Following actions taken to improve the experience for users, the evaluation was announced to selected open discussion lists in a phased programme during July 2002. Announcements were targetted at:

Figure 7.1. Chart of daily responses to evaluation Form 1(July-November

2002)

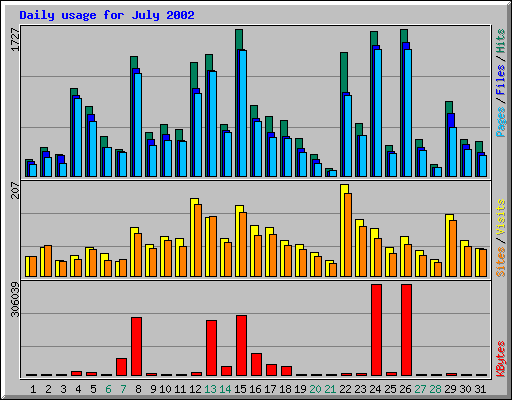

Figure 7.2. Citebase usage: summary statistics for July 2002 showing

number of distinct visits (yellow chart) to citebase.eprints.org (excludes

all hits from soton.ac.uk and from cs.odu.edu (DP9), but includes search

engines (effect visible in red chart))

It can be seen that the highest response to the evaluation during the

period of open announcements occurred between 12-14 July following announcements

to open access advocates (Figure 7.1), but Citebase usage in July was highest

on the 22nd (Figure 7.2) after announcements to library lists.

| Date (July) | No. of visits | Suspected source of users |

|---|---|---|

| 22nd | 207 | Delayed reaction to library mails over a weekend |

| 12th | 175 | OAI, Sept-Forum, FOS-Forum |

| 15th | 159 | D-Lib Magazine |

| 29th | 138 | PhysNet? |

| 8th | 109 | Possibly delayed reaction to JISC, DLI mails over a weekend |

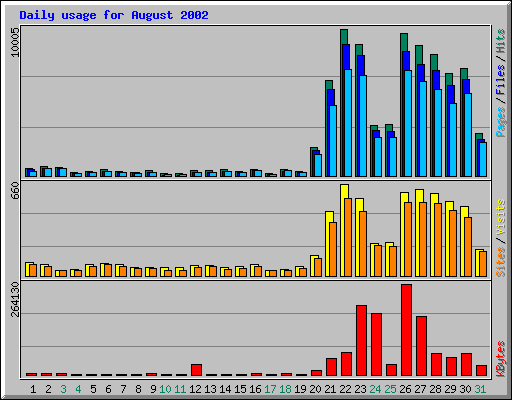

Figure 7.3. Citebase usage: summary statistics for August 2002 showing

number of distinct visits (yellow chart) to citebase.eprints.org (excludes

all hits from soton.ac.uk and from cs.odu.edu (DP9), but includes search

engines)

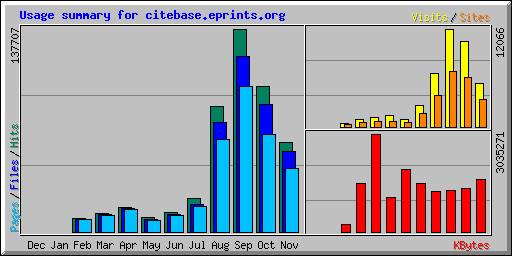

The impact of arXiv links on usage of Citebase was relatively much larger than that due to list announcements, as can be seen in Figure 7.4 in the column heights for July (list announcements) against August, September and October (arXiv links) (ignoring the red chart which emphasises the effect of Web crawlers rather than users).

Figure 7.4. Usage statistics for citebase.eprints.org from Dec 2001

to November 2002 (excludes all hits from soton.ac.uk and from cs.odu.edu

(DP9), but includes search engines)

*image saved on 15 November 2002

Table 7.2 puts the growth of Citebase usage (by visits) in perspective

over this period: prior to the evaluation (February-June), due to list

announcements (July), due to new arXiv links (August), and during the first

full month of arXiv links (September).

| February-June | July | August | September | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average daily visits | 25-45 | 85 | 211 | 402 |

| Highest daily visits | 95 (8th May) | 207 (22nd) | 660 (22nd) | 567 (4th) |

The effect of the arXiv links on the evaluation were materially different

from the mailed links, however, because the links were to Citebase, and

only indirectly from there to the evaluation (see section 3.4). Table 7.3

shows how efficiently Citebase users were turned into evaluators on the

best days for submission of evaluation Form 1. It shows how list announcements

taking users directly to the evaluation returned the highest percentage

of daily submissions from all Citebase users. Although overall usage of

Citebase generated by arXiv links was much larger than for list announcements,

this was not effectively translated into more submissions of the evaluation.

| Date | No. of evaluation forms returned (Figure 7.1) | Percentage of Citebase visitors that day |

|---|---|---|

| July 12th | 16 | 9.1 |

| July 13th | 8 | 6.1 |

| July 15th | 7 | 4.4 |

| July 22nd | 7 | 3.4 |

| July 8th | 6 | 3.4 |

| August 21st | 6 | 1.3 |

| August 23rd | 6 | 1.1 |

| August 27th | 6 | 1.0 |

| August 22nd | 6 | 0.9 |

ArXiv.org HTTP server daily usage (http://arxiv.org/show_daily_graph) shows c.15,000 hosts connecting each day, i.e. approximately 3.3% of arXiv visitors become Citebase users. The challenge for Citebase, highlighted by these figures, is to attract a higher proportion of arXiv users. Since September usage of Citebase has increased by 250%. What is not yet known is what proportion of arXiv usage is mechanical downloads, just keeping up with the literature, to be read later offline. Citebase will make little difference to this type of activity, but instead will help more active users, and here its proportionate share of users may already be much higher.

| Mathematicians | 13 | Computer scientists | 15 | Information scientists | 33 | Physicists | 69 | Other | 60 | Blank | 5 | Total | 195 |

The backgrounds of evaluators are broadly based, mostly in the sciences, but about 10% of users were non-scientists. This would appear to suggest greater expectation of OAI-based open access archives and services in the sciences, if this reflects a broad cross-section of the lists mailed (see section 7.1).

About a third of evaluators were physicists, although the number of physicists as a proportion of all users might have been expected to be higher given the concentration of Citebase on physics. (Physicists can be notoriously unfond of surveys, as the ArXiv administrators warned us in advance!)

Among non-scientists, as the highlighted comment below indicates, there may be a sense of exclusion. This is a misunderstanding of the nature of open access archives and services. No disciplines are excluded, but services such as Citebase can only act on major archives, which currently are mostly in the sciences. The primary exception is economics, which has distributed archives indexed by RePEc (http://repec.org/).

| User comment

"As usual, I find myself an "outsider" in discussions of things that will be important to me very soon. I find there is no category for me to go into. You guys need to look beyond geekdom to think about ordinary social scientists, librarians, educationists." |

It is true, if this is what is meant by the "outsider" above, that Q1.1 in this evaluation anticipated that evaluators would mostly be scientists of certain types, as shown in Figure 8.1. It must also be added that the Citebase services of impact-based scientometric analysis, measurement and navigation are intended in the first instance for research-users, rather than lay-users, because the primary audience for the peer-reviewed research literature is the research community itself.

Q1.2 Have you used the arXiv eprint archive before?

| Daily | Regularly | Occasionally (less than monthly) | No |

| 56 (50) | 26 (11) | 28 (3) | 79 (5) |

Physicists in this sample tend to be daily users of arXiv. Non-physicists, noting that arXiv has smaller sections on mathematics and computer science, tend to be regular or occasional users of arXiv (Figure 8.1). Beyond these disciplines most are non-users of arXiv, and thus would be unlikely to use Citebase given its present coverage.

Q1.3 If you have used arXiv, which way do you access arXiv papers? (you may select one or more)

Most arXiv users in this study access new material by browsing, rather than by alerts from arXiv. The relatively low ranking of the latter was unexpected. There is some encouragement for services such as Citebase (note, at this stage of the evaluation users have not yet been introduced to Citebase) in the willingness to use Web search and reference links to access arXiv papers (second and third most popular categories of access). It is possible, as mentioned above, that the Citebase evaluators were a biased sample of arXiv daily users who do not download mechanically.

Figure 8.2. Accessing arXiv papers

Q1.4 Had you heard of the Open Archives Initiative?

| Yes | No |

| 99 (11) | 86 (55) |

OAI is familiar to over half the evaluators, but not to many physicists

(Figure 8.3a). The latter is not surprising. OAI was originally motivated

by the desire to encourage researchers in other disciplines to build open

access archives such as those already available to physicists through arXiv,

although the structure of Open Archives, unlike arXiv, is de-centralised

(Lynch 2001).

a |

b |

Q1.5 Have you used any other OAI services? (you may select one or more)

| arc | 8 | myOAI | 10 | kepler | 6 | Other | 2 | No response | 178 |

Although OAI has made an impact among most non-physicist evaluators - again probably preordained through list selection - there is clearly a problem attracting these users to OAI services. Either current OAI services are not being promoted effectively, or they are not providing services users want -- or this may be merely a reflection of the much lower availability of non-physics OAI content to date! As an OAI service, this result shows the importance for Citebase of learning the needs of its users from this evaluation, and of continuing to monitor the views of users. More generally, this result suggests there are stark issues for OAI and its service providers to tackle. To be fair, the services highlighted on the questionnaire are mainly research projects. It is time for OAI services to address users.

| Q2.1 Who is the most-cited (on average) author on string theory

in arXiv?

Correct 141 (45) Incorrect 20 (8) No answer 34 (15) Q2.2 Which paper on string theory is currently being browsed most often in arXiv? Correct 133 (41) Incorrect 16 (8) No answer 46 (19) Q2.3 Which is the most-cited paper on string theory in arXiv? Correct 145 (48) Incorrect 9 (2) No answer 41 (18) Q2.4 Which is the most highly cited paper that cites the most-cited paper above? (critical point) Correct 122 (44) Incorrect 26 (5) No answer 47 (19) Q2.5 Which paper is most often co-cited with the most-cited paper above? Correct 133 (46) Incorrect 12 (3) No answer 50 (19) Q2.6a Download the full-text of the most-cited paper on string theory. What is the URL? Correct 124 (42) Incorrect 13 (3) No answer 58 (23) (Correct=Opcit linked copy 71 (15) +arXiv copy 53 (27)) Q2.6b In the downloaded paper, what is the title of the referenced paper co-authored with Strominger and Witten (ref [57])? Correct 105 (35) Incorrect 27 (9) No answer 63 (24) Q2.6c Did you use search to find the answer to 2.6b? No 118 (40); Yes 18 (3) |

Results from this exercise show that most users were able to build a short bibliography successfully using Citebase (Figure 8.4). The exercise introduced users to most of the principal features of Citebase, so there is a good chance that users would be able to use Citebase for other investigations, especially those related to physics. The yellow line in Figure 8.4a, indicating correct answers to the questions posed, shows a downward trend through the exercise, which is most marked for Q2.6 involving downloading of PDF full texts. Figure 8.4b, which includes results for physicists only, shows an almost identical trend, indicating there is not a greater propensity among physicists to be able to use the system compared with other users..

As anticipated, Q2.4 proved to be a critical point, showing a drop in correct answers from Q2.3. The upturn for Q2.5 suggests that user confidence returns quickly when familiarity is established for a particular type of task. Similarly, the highest number of correct answers for Q2 .3 shows that usability improves quickly with familiarity of the features of a particular page. At no point in Figure 8.4 is there evidence of a collapse of confidence or of unwillingness among users to complete the exercise.

The incidental issue of which PDF version users prefer to download, OpCit or arXiv version (Q2.6a), was not conclusively answered, and could not be due to the change in format on the Citebase records for papers (Table 4.1). It can be noted that among all users, physicists displayed a greater preference to download the arXiv version.

a |

b |

Physicists generally completed the exercise faster than other users (Figure 8.5a). Almost 90% of users (100% of physicists) completed the exercise within 20 mins, with approximately 50% (55% physicists) finishing within 10 mins. There appears to be some correlation between subject disciplines and level of arXiv usage with the time taken to complete the exercise (Figure 8.5), although neither correlation is statistically significant. Taken together these results show that tasks can be accomplished efficiently with Citebase regardless of the background of the user.

Time taken to complete section 2, ( ) physicists only

| 1-5 minutes | 5-10 | 10-15 | 15-20 | 20-25 | 25-30 | 30+ | ? | Total |

| 13 (6) | 60 (21) | 36 (14) | 17 (5) | 9 (0) | 6 (0) | 2 (0) | 5 (2) | 147 |

a |

b |

On the basis of these results there can be confidence in the usability of most of the features of Citebase, but the user comments in this section draw attention to some serious usability issues - help and support documentation, terminology - that must not be overshadowed by the results.

Links to citing and co-citing papers are features of Citebase that are valued by users (Figure 8.6), even though these features are not unique to Citebase. The decision to rank papers according to criteria such as these, and to make these ranking criteria selectable from the main Citebase search interface, is another feature that has had a positive impact with users. Citations/hit graphs appear to have been a less successful feature. There is little information in the data or comments to indicate why this might be, but it could be due to the shortcomings discussed in section 4 and it may be a feature worth persevering with until more complete data can be tested.

Figure 8.6. Most useful features of Citebase

Q3.2 What would most improve Citebase?

Users found it harder to say what would improve Citebase, judging from the number of 'no responses' (Figure 8.7). Wider coverage, especially in terms of more papers, is desired by all users, including physicists.

Figure 8.7. Improving Citebase

The majority of the comments are criticisms of coverage. Signs of the need for better support documentation reemerge in this section. Among features not offered on the questionnaire but suggested by users, the need for greater search precision stands out (Table 8.1).

|

|

Q3.3 What services would you use to compile a bibliography in your own work and field? (you may select one or more)

There is a roughly equal likelihood that users who participated in this survey will use Web-based services (e.g. Web search), online library services and personal bibliography software to create bibliographies (Figure 8.8). This presents opportunities for Citebase to become established as a Web-based service that could be integrated with other services. The lack of a dominant bibliography service, including services from ISI, among this group of users emphasises the opportunity (Table 8.2).

Figure 8.8. Creating personal bibliographies

|

|

Q3.4 How does Citebase compare with these bibliography services (assuming that Citebase covered other subjects to the degree it now covers physics)?

Citebase is beginning to exploit that opportunity presented by the lack of a dominant bibliography service (Figure 8.9), but needs to do more to convince users, even physicists, that it can become their primary bibliographic service.

Figure 8.9. Comparing Citebase with other bibliography services

Attempts to correlate how Citebase compares with other bibliographic services with other factors considered throughout the evaluation - with subject discipline, with level of arXiv usage, and time taken to complete section 2 - showed no correlations in any case (Figures 8.10-8.12). This means that reactions to Citebase are not polarised towards any particular user group or as a result of the immediate experience of using Citebase for the pre-set exercise, and suggests that the principle of citation searching of open access archives has been demonstrated and need not be restricted to current users.

Figure 8.10. Correlation between subject disciplines and views on

how Citebase compares with other bibliography services (x axis:

physics=4, maths=3, computer=2, infoScience=1, other=0; y axis:

citebase compares "very favourably"=2, "favourably"=1, no response=0, "unfavourably"=-1),

correlation=

-0.00603, N=190, p<0.924. There is no meaningful correlation

Figure 8.11. Correlation between level of arXiv usage and views

on how Citebase compares with other bibliography services (x

axis: daily usage=4, regular usage=3, occasional usage=2, no usage=1; y

axis: citebase compares "very favourably"=2, "favourably"=1, no response=0,

"unfavourably"=-1), correlation= 0.014765, N=190, p<0.840. There

is no meaningful correlation

Figure 8.12. Correlation between views on how Citebase compares

with other bibliography services and time taken to complete section 2 (xaxis:

citebase compares "very favourably"=2, "favourably"=1, no response=0, "unfavourably"=-1),

correlation=

0.029372, N=144, p<0.727. There is no meaningful correlation

There is little opportunity in this section for users for users to compare, contrast and discuss features of Citebase that differentiate it from other services. In particular, Citebase offers access to full texts in open access eprint archives. It is an aspect that needs to be emphasised as coverage and usage widen. Comments reveal that some users appreciate this, although calls for Citebase to expand coverage in areas not well covered now suggest this is not always understood. It is not possible for Citebase to simply expand coverage unless there is recognition and prior action by researchers, as authors, of the need to contribute to open access archives. One interpretation is that users in such areas do not see the distinction between open access archives and services and paid-for journals and services, because they do not directly pay for those services themselves - these services appear to be free.

Form 2 could have been longer and explored other areas, but this may have inhibited the number of responses. As Form 2 was separate from Form 1 it was not expected that all users would progress this far. Of 195 users who submitted the first form, 133 completed Form 2 (http://www.ecs.soton.ac.uk/~aw01r/citebase/evalForm2.htm).

The summary results by question and section are shown in Table 9.1 and

Figure 9.1.

| Question | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| Average score by Q. | 0.92 | 0.79 | 1.39 | 1.05 | 0.41 | 1.17 | 0.83 | 1.02 | 0.65 | 1.07 | 1.42 | 0.99 | 0.92 | 0.27 | 0.57 | 0.26 |

| Section | Impression | Command | Effectiveness | Navigability | ||||||||||||

| Average by section | 1.04 | 0.86 | 1.03 | 0.51 | ||||||||||||

a b

b

Figure 9.1. Average user satisfaction scores: a, by question, b,

by section

The highest score was recorded for Q11, indicating that on average users were able to find the information required most of the time. Scoring almost as high, Q3 shows users found the system frustrating to use only some of the time.

The questions ranked lowest by score, Q14 and Q16, suggest that users agree weakly with the proposition that there were plenty of ways to find the information needed, and disagreed weakly with the proposition that it is easy to become disoriented when using the system.

Scores by section indicate that, overall, users formed a good impression of Citebase. They found it mostly to be effective for task completion (confirming the finding of Form 1, section 2), and they were able to control the system most of the time. The lower score for navigability suggests this is an area that requires further consideration.

It should be recalled that responses were scored between 2 and -2, depending on the strength of the user's reaction. In this context it can be seen that on average no questions or sections scored negatively; six questions scored in the top quartile, and two sections just crept into the top quartile.

Among users, scores were more diverse, with the total user score varying from 31 (maximum score possible is 32) to -25. Other high scores included 29, 28 and 27 (by five users). Only eight users scored Citebase negatively.

Submission of Form 2 completed the evaluation for the user.

The exercise to evaluate Citebase had a clear scope and objectives. Within the scope of its primary components, the search interface and services available from a Citebase record, it was found Citebase can be used simply and reliably for resource discovery. It was shown tasks can be accomplished efficiently with Citebase regardless of the background of the user.

The principle of citation searching of open access archives has been demonstrated and need not be restricted to current users.

More data need to be collected and the process refined before it is as reliable for measuring impact.As part of this process users should be encouraged to use Citebase to compare the evaluative rankings it yields with other forms of ranking.

Citebase is a useful service that compares favourably with other bibliographic services, although it needs to do more to integrate with some of these services if it is to become the primary choice for users.

The linked PDFs are unlikely to be as useful to users as the main features of Citebase. Among physicists, linked PDFs will be little used, but the approach might find wider use in other disciplines where PDF is used more commonly.

Although the majority of users were able to complete a task involving all the major features of Citebase, user satisfaction appeared to be markedly lower when users were invited to assess navigability than for other features of Citebase.

Perhaps one of the most important findings of the evaluation is that Citebase needs to be strengthened in terms of the help and support documentation it offers to users.

Coverage is seen as a limiting factor. Although Citebase indexes over 200,000 papers from arXiv, non-physicists were frustrated at the lack of papers from other sciences. This is a misunderstanding of the nature of open access services, which depend on prior self-archiving by authors. In other words, rather than Citebase it is users, many of whom will also be authors, who have it within their power to increase the scope of Citebase by making their papers available freely from OAI-compliant open access archives. Citebase will index more papers and more subjects as more archives are launched.

The wider objectives and aspirations for developing Citebase are to help increase the open-access literature. Where there are gaps in the literature - and there are very large gaps in the open-access literature currently - Citebase will motivate authors to accelerate the rate at which these gaps are filled. Research funders can provide stronger motivation for authors to self-archive by mandating that assessable work is to be openly accessible online (Harnad et al. 2003).

We are grateful to Paul Ginsparg, Simeon Warner and Paul Houle at arXiv Cornell for their comments and feedback on the design of the evaluation and their cooperation in helping to direct arXiv users to Citebase during the evaluation. Eberhard Hilf and Thomas Severiens at PhysNet and Jens Vigen at CERN were also a great help in alerting users to the evaluation.

Our local evaluators at Southampton University gave us confidence the evaluation was ready to be tackled externally. We want to thank Iain Peddie, Shams Bin Tariq, David Crooks, Jonathan Parry (Physics Dept.) and Muan H. Ng, Chris Bailey, Jing Zhou, Norliza Mohamad Zaini, Hock K.V. Tan and Simon Kampa.(IAM Dept.).

Finally, we thank all our Web evaluators, who must remain anonymous, but this in no way diminishes their vital contribution.

Bergmark, D. and Lagoze, C. (2001) "An Architecture for Automatic Reference

Linking". Cornell University Technical Report, TR2001-1842, presented at

the 5th European Conference on Research and Advanced Technology for

Digital Libraries (ECDL), Darmstadt, September

http://www.cs.cornell.edu/cdlrg/Reference%20Linking/tr1842.ps

Bollen, Johan and Rick Luce (2002) "Evaluation of Digital Library Impact

and User Communities by Analysis of Usage Patterns". D-Lib Magazine,

Vol. 8, No. 6, June

http://www.dlib.org/dlib/june02/bollen/06bollen.html

Chen, C. and Carr, L. (1999) "Trailblazing the literature of hypertext:

An author co-citation analysis (1989-1998)". Proceedings of the 10th

ACM Conference on Hypertext (Hypertext '99), Darmstadt, February

http://www.ecs.soton.ac.uk/~lac/ht99.pdf

Crow, R. (2002) "The Case for Institutional Repositories: A SPARC Position

Paper". Scholarly Publishing & Academic Resources Coalition, Washington,

D.C., July

http://www.arl.org/sparc/IR/ir.html

Darmoni, Stefan J., et al. (2002) Reading factor: a new bibliometric

criterion for managing digital libraries. Journal of the Medical Library

Association, Vol. 90, No. 3, July

http://www.pubmedcentral.gov/picrender.fcgi?action=stream&blobtype=pdf&artid=116406

Garfield, Eugene (1994) "The Concept of Citation Indexing: A Unique

and Innovative Tool for Navigating the Research Literature". Current

Contents, January 3rd

http://www.isinet.com/isi/hot/essays/citationindexing/1.html

Guédon, Jean-Claude (2001) "In Oldenburg's Long Shadow: Librarians,

Research Scientists, Publishers, and the Control of Scientific Publishing".

ARL

Proceedings, 138th Membership Meeting, Creating the Digital Future,

Toronto, May

http://www.arl.org/arl/proceedings/138/guedon.html

Gunn, Holly (2002) "Web-based Surveys: Changing the Survey Process".

First

Monday, Vol. 7, No. 12, December

http://firstmonday.org/issues/issue7_12/gunn/index.html

Gutteridge, Christopher (2002) "GNU EPrints 2 Overview". Author eprint,

Dept. of Electronics and Computer Science, Southampton University, October,

and in Proceedings 11th Panhellenic Academic Libraries Conference,

Larissa, Greece, November

http://eprints.ecs.soton.ac.uk/archive/00006840/

Harnad, S. (2001) "Why I think research access, impact and assessment

are linked". Times Higher Education Supplement, Vol. 1487, 18 May,

p. 16

http://www.cogsci.soton.ac.uk/~harnad/Tp/thes1.html

(extended version)

Harnad, S. (2002) "UK Research Assessment Exercise (RAE) review". American

Scientist September98-Forum, 28th October

http://www.ecs.soton.ac.uk/~harnad/Hypermail/Amsci/2325.html

Harnad, Stevan, Les Carr, Tim Brody and Charles Oppenheim (2003) "Mandated

online RAE CVs Linked to University Eprint Archives". Ariadne, issue

35, April

http://www.ariadne.ac.uk

/issue35/harnad/intro.htm

Hitchcock, Steve (2003) "Metalist of open access eprint archives: the genesis of institutional archives and independent services". Submitted to ARL Bimonthly Report

Hitchcock, Steve, Donna Bergmark, Tim Brody, Christopher Gutteridge,

Les Carr, Wendy Hall, Carl Lagoze, Stevan Harnad (2002) "Open Citation

Linking: The Way Forward". D-Lib Magazine, Vol. 8, No. 10, October

http://www.dlib.org/dlib/october02/hitchcock/10hitchcock.html

Hitchcock, S. et al. (2000) "Developing Services for Open Eprint

Archives: Globalisation, Integration and the Impact of Links". Proceedings

of the Fifth ACM Conference on Digital Libraries, June (ACM: New York),

pp. 143-151

http://opcit.eprints.org/dl00/dl00.html

Hitchcock, S. et al. (1998) "Linking Electronic Journals: Lessons

from the Open Journal Project". D-Lib Magazine, December

http://www.dlib.org/dlib/december98/12hitchcock.html

Hunt, C. (2001) "Archive User Survey". Final year project, ECS Dept,

University of Southampton, May

http://www.eprints.org/results/

Kurtz, M. J., G. Eichorn, A. Accomazzi, C. Grant, M. Demleitner, S.

S. Murray, N. Martimbeau, and B. Elwell (2003) "The NASA astrophysics data

system: Sociology, bibliometrics, and impact". Author eprint, submitted

to Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology

http://cfa-www.harvard.edu/~kurtz/jasist-submitted.ps

Lawrence, Steve (2001) "Free Online Availability Substantially Increases

a Paper's Impact". Nature Web Debate on e-access, May

http://www.nature.com/nature/debates/e-access/Articles/lawrence.html

Lawrence, S., Giles, C. L. and Bollacker, K. (1999) "Digital Libraries

and Autonomous Citation Indexing". IEEE Computer, Vol. 32, No. 6,

67-71

http://www.neci.nj.nec.com/~lawrence/papers/aci-computer98/

Lynch, Clifford A. (2001) "Metadata Harvesting and the Open Archives

Initiative". ARL Bimonthly Report, No. 217, August

http://www.arl.org/newsltr/217/mhp.html

Merton, Robert (1979) "Foreward". In Garfield, Eugene Citation Indexing: Its Theory and Application in Science, Technology, and Humanities (New York: Wiley), pp. v-ix http://www.garfield.library.upenn.edu/cifwd.html

Nielsen, Jakob (2000) "Why You Only Need to Test With 5 Users". Alertbox,

March 19th

http://www.useit.com/alertbox/20000319.html

Small (1973) "Co-citation in the Scientific literature: A New Measure

of the Relationship Between Two Documents". Journal of the American

Society for Information Science, Vol. 24, No. 4, July-August;

reprinted in Current Contents, No. 7, February 13th, 1974,

http://www.garfield.library.upenn.edu/essays/v2p028y1974-76.pdf

Suber, Peter (2003) "Removing the Barriers to Research: An Introduction

to Open Access for Librarians". College & Research Libraries News,

64, February, 92-94, 113

http://www.earlham.edu/~peters/writing/acrl.htm

Suber, Peter (2002) "Larger FOS ramifications". FOS-Forum list server,

2nd July

http://www.topica.com/lists/fos-forum/read/message.html?mid=904724922&sort=d&start=240

Van de Sompel, H. and Lagoze, C. (2002) "Notes from the Interoperability

Front: A Progress Report from the Open Archives Initiative". 6th European

Conference on Research and Advanced Technology for Digital Libraries (ECDL),

Rome, September

http://lib-www.lanl.gov/%7Eherbertv/papers/ecdl-submitted-draft.pdf

Young, Jeffrey R. (2002) "Superarchives' Could Hold All Scholarly Output".

Chronicle

of Higher Education, July 5th

http://chronicle.com/free/v48/i43/43a02901.htm