Digital Preservation Service Provider Models for Institutional

Repositories: towards distributed services

Steve Hitchcock, Tim Brody, Jessie M.N. Hey and Leslie

Carr

Preserv Project, IAM Group, School

of Electronics and Computer Science,

University of Southampton, SO17 1BJ, UK

Email:

sh94r@ecs.soton.ac.uk

Preserv is a JISC-funded project within the

programme

Supporting Digital Preservation and Asset Management in Institutions.

Find out more about Preserv.

Version history

Published

in D-Lib Magazine, Vol. 13,

No. 5/6, May/June 2007

16 May 2007, final draft,

including late edits for D-Lib

publication

This version

25 January 2007, first draft. It includes edited and updated

material from an earlier paper Preservation

Metadata for Institutional Repositories (February 2006), focussing

on preservation

service models and omitting coverage

of preservation metadata. There is a companion paper on Preservation

Metadata for Institutional Repositories: applying PREMIS.

Abstract

Digital preservation can encompass a range of

activities, from simple replication and storage to more complex

transformation, depending on the source and target content to be

preserved, and the assessed value of the content and level of risk to

the content. Invariably these activities require planning and in most

cases begin with a need to know the technical format of the target

content. In this case the source and target contents are deposited in institutional repositories (IRs). The

Preserv project set out

to investigate the use of The National Archives’ (TNA) PRONOM-DROID

service (PRONOM

is the online registry of technical information; DROID is the

downloadable

file

format identification tool) for file format identification on two pilot

IRs using EPrints software, and instead produced format

profiles (Preserv

profiles) of

over 200 repositories presented via the Registry of Open Access

Repositories

(ROAR). Thus

a primary element of preservation planning has been shown to be

possible based

on a standard Web interface (OAI) and no formal arrangement between

repository

and provider. The implications of this go beyond the numbers towards a

reconceptualisation of preservation service provider models.

Repositories and

providers can

shape preservation services at different cost levels that could range

from comprehensive

‘black-box’ preservation to pick-and-mix lightweight Web-based services

that

build on the common starting point, format identification. The paper

describes the evolution of a series of models that have informed

progress towards this conception of flexible and distributed

preservation services for IRs.

Introduction

How are institutional repositories (IRs) to preserve the digital

content for

which

they accept responsibility? Until now much emphasis has been placed on

the role of repository software. Two of these softwares, notably DSpace

(http://www.dspace.org/)

and Fedora (http://www.fedora.info/), have promoted support for

preservation as a key feature. In

contrast, the first software designed for IRs, EPrints

(http://www.eprints.org/), has offered

less explicit support for preservation. In truth, reliance on

repository software alone will not be sufficient: "it seems obvious

that no existing software application could serve on its own as a

trustworthy preservation system. Preservation is the act of physically

and intellectually protecting and technically stabilizing the

transmission of the content and context of electronic records across

space and time, in order to produce copies of those records that people

can reasonably judge to be authentic. To accomplish this, the

preservation system requires natural and juridical people,

institutions, applications, infrastructure, and procedures." (Wilczek and Glick 2006)

Repository support

teams need to engage in preservation management, planning and policy.

Even then more specialised technical preservation tasks might best be

outsourced. The Preserv project has been investigating with possible

preservation service providers just what services might serve IRs and

how they might be delivered. This paper illustrates the models that

have been developed to inform the investigations, and shows how the

general preservation service provider model has evolved, based on the

project's experiences, away from the idea of a monolithic service

provider towards more discrete, flexible and distributed Web-based

preservation services.

First we need to explain what is meant by the term 'preservation' as it

applies to the digital objects and environments that Preserv is

concerned with.

What is 'preservation'?

Most collectors know that storing physical collectibles in a container

in an attic is likely to provide more assurance of retrieval than

simply throwing items on a coffee table. This is the equivalent of

depositing an electronic paper in an IR rather than simply uploading it

to a

personal server and Web page. The organisation of the IR together

with the commitment of the sponsoring institution will provide

greater assurance than a server with unknown support looking forward.

Attic storage is hardly a complete solution,

however. In the long

term, even physical materials suffer some degradation. The determined

collector could, at a cost, provide further protection against these

risks by acquiring special containers. The

equivalent process of degradation for digital materials is typically

caused by format obsolescence - due to changes in software

applications technology, often regarded as a rapid process in

comparison with degradation of physical materials - and can be

ameliorated by specialised technical processes such as format

migration. In both cases, the extended risks to physical and digital

materials might be most cost-effectively tackled by specialist

preservation services. For

information materials like books and journals, these services have

traditionally been offered by libraries and

archives, and such organisations might be well positioned to serve

digital sources too.

'Preservation' thus covers a wide range of activities, from storage to

transformation, depending on the

nature of the resources and the source, and the range of preservation

services could be equally wide. Since such services are not yet widely

practised or available, a useful starting point is to consider what is

known about the target content in IRs.

Evolution of institutional repositories

It is helpful to consider

what

IRs are, what they do and where the idea comes from because this

relatively recent development has been subject to misunderstanding,

confusion and attempted re-inventions.

An IR provides access to the content and materials produced by members

of the institution, typically a university or other educational

establishment. The impetus for IRs was boosted by the Open

Archives

Initiative (OAI) in 1999, not to be confused in preservation terms with

the Open Archival Information System (OAIS 2002, Hirtle 2001). Although

institutionally-based, or more typically departmental, 'archives' were

known before this, especially in areas such as computer science and

economics that were served by NCSTRL and RePEc, respectively, OAI

introduced the Protocol for Metadata Harvesting (OAI-PMH) to provide

common services that could operate over more

general, independent sites (Lynch 2001). Search is the most obvious

example of

such a service. OAI-PMH enables compliant sites to be interoperable, thus making

institutional, rather than only disciplinary, repositories visible and

viable. For

the first time institutions such as universities have the ability to

capture, store and disseminate

copies of the

published work of their own researchers. The significance of this

cannot be underestimated.

OAI was aimed initially at eprint archives (Van de Sompel and Lagoze

2000), and although the protocol was

soon applied to other digital library content, the first

software to

support it was EPrints, developed at Southampton University and on

which we

base our work. EPrints is software for

building IRs

that capture and

provide open access to an

institution's research outputs, which are deposited directly by

authors in principle using the

version they created, a process known as 'self-archiving'.

One of the consequences of this approach is that IRs incur low cost per

item deposited, in turn creating the conditions for open access:

immediate and permanently free access to content. As such,

where digital preservation might generally be

concerned with preserving access, for IRs it is concerned with

preserving open access, which

has cost implications.

EPrints first appeared in 2000, and an OAI-PMH 1.0-compliant version

was

announced on the

same day this breakthrough version of the protocol was unveiled in

January 2001 (Harnad 2001, OAI 2001). This application to IRs was

reinforced with the emergence of DSpace software the following

year, and other IR softwares have followed since.

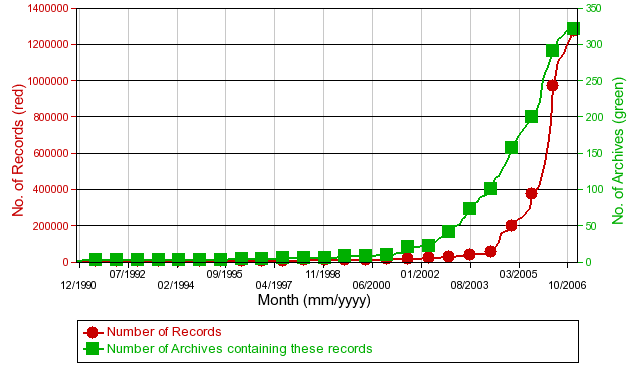

Growth in the number of IRs has accelerated since 2002 and, despite

some lag in time, there has been corresponding growth in the volume of

content in IRs (Figure

1), as revealed by the Registry of Open Access Repositories (ROAR

http://roar.eprints.org/). Among repository directories, "on December

31, 2006, OAIster

(launched in 2002) listed 726 OA,

OAI-compliant repositories worldwide; last year at the same time,

OAIster listed 578, showing a 25% increase in one

year. Last year OAIster listed a total of

6,255,599 records from the repositories it covered, and this year it

listed 9,931,910, a 59% increase." (Suber 2007)

Figure

1. Growth of institutional repositories and contents, generated from

the Registry of Open Access Repositories (ROAR) on 5 January 2007.

Charts all repositories flagged as 'Research Institutional' in the ROAR

database

The fundamental requirements of repositories were characterised by

Heery and Anderson (2005):

- content is deposited in a repository, whether by the content

creator,

owner or third party

- the repository architecture manages content as well as metadata

- the repository offers a minimum set of basic services e.g. put,

get,

search, access control

- the repository must be sustainable and trusted, well-supported

and

well-managed

IRs are additionally characterised by the institution and the type of

content it requires and permits to be deposited and for what purpose,

most commonly research outputs for open access.

This description of what IRs are and what they represent is not to say

that the role and target content of IRs won't evolve

legitimately and in an informed way to serve institutional needs and

research purposes, as suggested by Dempsey (2006).Other types of

content, such as research data sets

(Lyon et al. 2004), theses,

reports and multimedia can be

deposited and managed within EPrints-based IRs, but not all

types of content produced in universities -- teaching and learning

materials, administrative documents, for example -- are best stored in

IRs. Such materials may require more specialised submission and

updating facilities, and may need to restrict access.

Suber (2006)

predicted "a continuing tension between the narrow

conception of institutional repositories (to provide OA for eprints)

and the broad conception of IRs (to provide OA for all kinds of digital

content, from eprints to courseware, conference webcasts, student work,

digitized library collections, administrative records, and so on, with

at least as much attention on preservation as access). But I have to

predict that the broad conception will prevail. Universities that

launch general-purpose archiving software will have active constituents

urging them to take full advantage of it."

Taking the age of most repositories into account, the need for

preservation is

perhaps less critical than for older digital content sources, but other

factors such as growth and diversity point towards a

more urgent need to plan for preservation by the more content-rich

repositories.

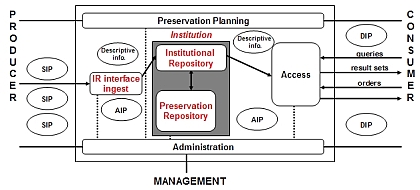

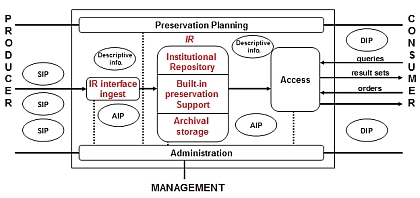

Three OAIS preservation models for IRs

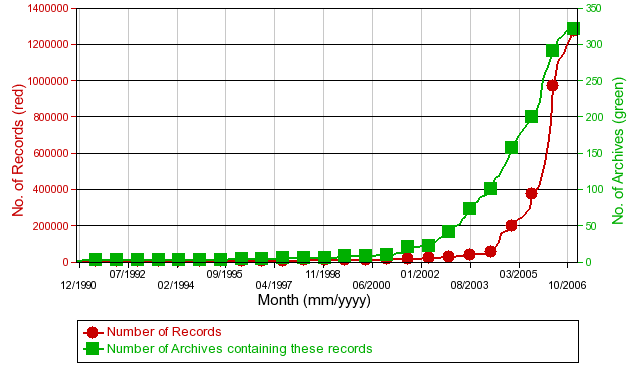

Having defined the target content for preservation services in terms of

IRs, we

can

consider the types of services that can be offered. The OAIS reference

model

(Figure 2a) provides a framework in which we can construct these

services (OAIS

2002).

At a very general level it can be seen that IRs provide a similar range

of functionality as found in OAIS -- input and output, data management

and storage. OAIS imposes more formality and discipline on these

processes for the purpose of long-term preservation. Thus deposit

becomes ingest, and we are

concerned with archival storage,

all enveloped by preservation planning, administrative and management

roles. To understand these distinctions and these support processes,

see the excellent Cornell tutorial (2003).

Information in this system is managed in packages: submission

information packages (SIPs) at point of ingest, archival information

packages (AIPs) in the preservation store, and dissemination

information packages (DIPs) for access by users or other services.

Within the types of

services we could construct we wish to support a range of business

models to allow IRs some flexibility in managing the preservation risk

in terms of their real resources, leading to the following proposed

models:

- service

provider model (service provider is OAIS, Figure 2b) the original and

core Preserv project model (Hitchcock et

al.

2005)

- institutional

model (institution is OAIS, Figure 2c), an institution may have

more than one repository, e.g. EPrints-Fedora

- software

model (repository is OAIS, Figure 2d), preservation features built

into IR software

Figure

2. Three preservation models based on OAIS: a, Base OAIS functional

model; b, Service provider model; c, Institutional model; d. IR model

The basis of the three service models in the formal OAIS model are

apparent in Figure 2. Representations of the OAIS reference model are

ubiquitous in

the digital preservation literature and may differ in presentation if

rarely in detail; for reference, this version (Figure 1a) was taken

from a

presentation by Day (2003). The changes in the service models are

shown

in red and are all focussed on the ingest-data management-archival

storage roles and the relations between these as shown by the

connecting arrows. Since access is a primary feature of IRs it has been

assumed that support services would not need to replicate this

function. In the service provider model a case could be made

to re-introduce the arrow connecting the service provider and the

access point (e.g. EVIE 2006), depending on the agreement between the

IR and

service provider partners.

The three models illustrated have no specific costs attached, but

represent a hierarchy in terms of level of cost (from Figure 2b highest

down to 2d) that might be incurred

to support preservation, based on Chapman's (2003) observation: "though

quantity, quality and size of the digital materials ingested

has

an impact on scale, the cost of long term digital sustainability

correlates more to the range of digital services offered." The range of

services offered by the service provider (Figure 2b) is clearly

potentially greater and

more flexible than the latter two, with the software model providing a

baseline requirement.

Other models might include federated and network models. These models

are beyond the immediate scope of

this paper, but it is worth highlighting some examples. A

prominent federated example is LOCKSS (Rosenthal et al. 2005), which focusses on

journal

applications rather than more heterogeneous collections such as in IRs,

and is predicated on the idea that the risk of data loss can be reduced

simply by copying and transfer of content between trusted partners.

The MetaArchive project (http://www.metaarchive.org/) has

extended the LOCKSS approach to at-risk digital content from various

digital repositories focussing on the the culture and history of the

American South.

Integration of Storage Resource Broker (SRB) with DSpace (Declerck and

Frymann 2004) illustrates a network preservation approach. "SRB is

a very robust, sophisticated storage manager that offers

essentially unlimited storage and straightforward means to replicate

(in simple terms, backup) the content on other local or remote storage

resources." (http://www.dspace.org/technology/system-docs/storage.html)

Similarly the Shared

Infrastructure

Preservation Models project investigated how

dissemination of repository content can be 'piggybacked' on top of

existing network services such as email and Usenet traffic: "Long-term

persistence of the replicated repository may be achieved thanks to

current policies and procedures which ensure that email messages and

news posts are retrievable for evidentiary and other legal purposes for

many years after the creation date. While the preservation issues of

migration and emulation are not addressed with this approach, it does

provide a simple method of refreshing content with various partners for

smaller digital repositories that do not have the administrative

resources for more sophisticated solutions." (Smith et al. 2006)

Preservation service provider model

The preservation service provider model was broadly outlined in terms

of shared, or third-party, preservation services by Beagrie (2002),

while RLG-OCLC (2002) reported the need for third-party

preservation services to fulfill the need for trusted digital

repositories. This model was proposed

for IRs by James et al.

(2003). Referring to this as a disaggregated

OAIS-compliant model,

Knight (2005) extended the idea to a model-based, rather than

evidence- or experience-based, analysis. Knight presented a detailed

breakdown of the model and workflow from the service provider's

perspective. In this case the service provider is represented by the

Sherpa-DP project. Experience is likely to

bring both more complexity and more clarity.

One particular type of content already subject to emerging preservation

services are electronic theses and dissertations (ETDs). While theses

have long been collected by national libraries, work at the

German National Library is advancing towards providing a preservation

framework for ETDs

(Wollschlaeger 2006). The Repository Bridge project demonstrated how

ETDs could be harvested using OAI and METS from Welsh IRs to a

Fedora-based repository at the National Library of Wales (Lewis and

Bell 2006), while Santhanagopalan et

al. (2006) harvested OAI content to a LOCKSS network involving

six Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (NDLTD)

repositories.

Extending this approach to all contents in IRs, so far the only planned

example of IR curation on a national scale Steenbakkers 2004) .

In the first instance these initiatives, as with the federated and

network examples, principally tested mechanisms

to transfer content between originating repositories and preservation

services or preservation networks. Moving the focus away from ETDs as

the source content, the Archive Ingest and Handling Test (AIHT)

similarly investigated the effects of content transfer.

The

AIHT practical preservation strategy will require "mechanisms for

continuous transfer of content from the wider world into the hands of

preserving institutions. The AIHT is designed to test the feasibility

of transferring digital archives in toto from one institution to

another" (Shirky 2005). This approach involving more than one agency in

content

management parallels our service provider model outlined below. AIHT

reveals important practical experience, although there are

some differences with anticipated preservation

service models for IRs. For example, in AIHT:

- There is no scope for interaction between creator and archive

- There is no moderated ongoing transfer process or protocol, just

a single disc of compressed data containing all files

- There is no business model (i.e. who is doing what for whom, and

why)

- The scope of the test archive may or may not reflect a typical

profile of an IR

Of the AIHT exemplars. that described by DiLauro et al. (2005) is

instructive for IR applications, being concerned with ingest into,

and transfer between, Fedora and DSpace-based archival stores.

While replication and storage can provide some support for

preservation, it is not a complete solution in the longer term because

of the effects of format obsolescence requiring more expert support.

Given the low age of most IRs this has not yet become a major issue,

and there are few examples currently of preservation services that go

beyond simple storage. Cornell's File Format and Media Migration

Pilot Service is an interesting exception, since it attempted to

retrieve older legacy materials, and was concerned not just with format

obsolescence but also media obsolescence, for example, the problem of

old disc and tape technologies (Entlich and Buckley 2006).

Perhaps

the most revealing point is left to the penultimate paragraph, however:

"We

believe a superior alternative is to establish institutional

repositories in which faculty are encouraged to deposit their work."

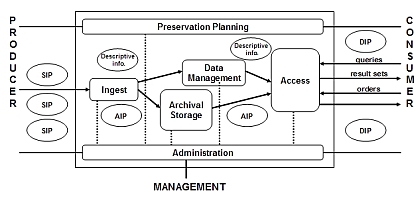

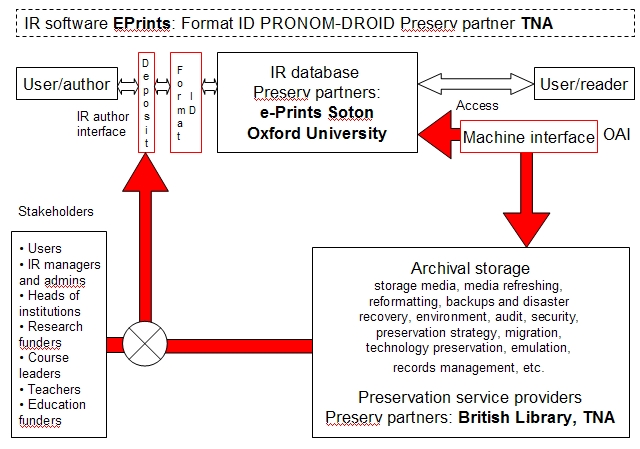

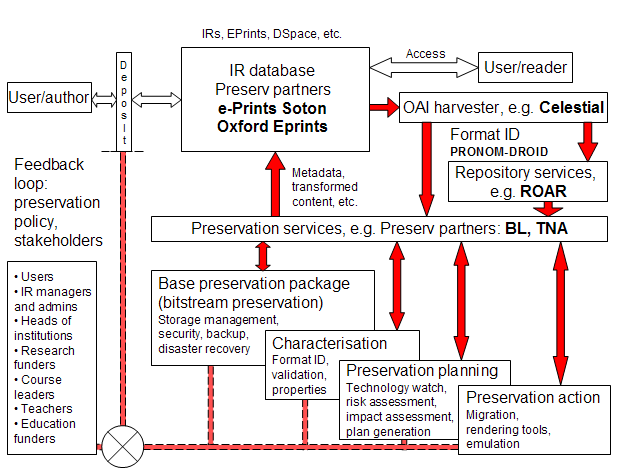

The service provider model to be adopted

in the Preserv project was developed in stages in Hitchcock

(2005). This model is formalised in Figure 3. A notable feature of the

illustrated model is the integration

of an automated file format identification tool, PRONOM-DROID,

developed by The National Archives (Brown 2005). The service provider

model again fits well with an OAI

application, which as we have seen is core to IR software, as OAI is

predicated on the data provider-service provider relationship (Lynch

2001). The archival storage, or service provider, element in principle

covers the full range of preservation services, from bit-level storage

to migration and emulation. At this stage this can be viewed as a

'black box' approach from the IR perspective because the preservation

activities are assumed to be performed entirely by the service provider

based on an agreed plan. We will soon begin to see this aspect of the

model change, however, towards a more interactive relationship between

preservation service and IR.

Figure

3. Schematic of Preserv service provider model, showing IR functions,

format ID tool and OAI interface to preservation service provider

As in Knight (2005), the Preserv model as presented easily lends itself

to

analogy

with the ubiquitous OAIS representation. In terms of the main OAIS

functionality -- ingest, data management, storage,

dissemination, etc. -- these models highlight how responsibilities

might be shared between partners. For example, in the service provider

model the IR could be OAIS-compliant, but it need not

necessarily be if

the service provider delivers that compliance. At the other extreme, in

the software model

where there is no other partner, the IR clearly has to be OAIS-aware to

provide a minimal level of compliance.There are

essentially three variations:

- the whole illustrated model forms an OAIS unit (as in Figure 2b)

- both partners -- IR and service provider -- are OAIS-compliant

- the service provider is OAIS-compliant

In IR terms the the formalisation of the deposit interface to

embrace

the requirements of OAIS ingest has particular significance: "until it

becomes common practice to integrate

digital stewardship and preservation concerns into the entire digital

content lifecycle -- especially front-end content creation --

most digital preservation workflows intended to be inclusive will be

reactive instead of prescriptive." (Anderson et al. 2005). IRs are some way from

being able to impose on authors content creation rules to support

preservation.

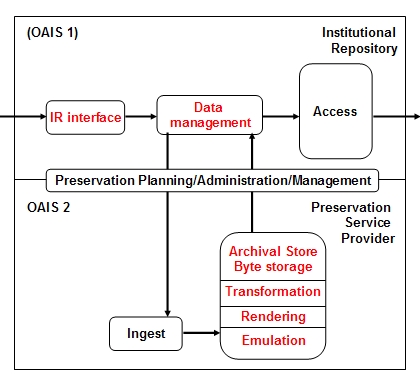

In Preserv one service

provider partner is the British Library (BL), which of course will

offer an

OAIS service. Thus the second of the three variations is most likely to

be the case. Figure 4 shows two simplified, co-joined OAIS models

representing the IR and the service provider. The OAIS administrative

functions are shown shared between the two partners pending further

investigation into this model to determine practical allocations.

Figure

4. Two OAIS repositories in Preserv preservation service provider

scenario

Figure 4 also explodes the service provider into a range of optional

services, which were informed by the BL. While the first two - byte

storage and transformation - focus on data ingest, the

latter two services - rendering and emulation - are concerned with

dissemination and presentation.

These services further differentiate the cost options. What is striking

is that each of these services is different to the extent it changes

the relationship between the service provider and the repository.

Preservation

need no longer be a monolithic service in this model. By choosing

services based on a

developed institutional profile this potentially changes the relation

from a simple 'you give us the data and we store it' to a more tailored

and interactive partnership. In the next section we see how this more

flexible model can be developed further.

Distributed preservation services: The impact of PRONOM-ROAR

There are sometimes moments in a project's development when

hypothetical models are overturned by practical experience. The trick

is to spot this tipping point and to adapt the model against the

prevailing wisdom of the project. Preserv encountered such a moment,

and was transformed.

We had begun to implement the model of Figure 3, starting with the use

of PRONOM-DROID to profile the formats contained in two partner

repositories at Oxford and Southampton universities. This proceeded

pretty much to

plan. Although not all formats were successfully recognised initially,

we were able to work locally with the repository managers, and feedback

to TNA led to refinements to PRONOM-DROID format database and ID tool.

The problem was largely resolved. The issue we now faced was where to

place format ID in the schematic: within the author deposit interface

to the IR, a notoriously sensitive area for IRs, or as a service to the

repository manager.

A secondary issue was scalability to many more repositories. As we have

seen, ROAR provides important quantitative data on the growth of

repositories. Data to ROAR is provided by an OAI harvesting service

called Celestial. Both are developed at Southampton University

independently of Preserv by Tim Brody, a member of the project team.

Brody moved the format ID process from the repository to the OAI

service provider, running DROID against the content harvested by

Celestial, and presenting a rudimentary interface to the results, shown

as links to Preserv profiles, through ROAR. By combining PRONOM-DROID

and ROAR through Web services, the number of repositories with format

profiles leapt from two to over 200. The features of PRONOM-ROAR are

explained in an illustrated guide

(http://trac.eprints.org/projects/iar/wiki/Profile).

Now the thinking about preservation services changes. First the

relation is no longer between PRONOM and a repository, but with an

intermediate service. Second, accurate format ID may be a prerequisite

for preservation planning, but alone it is not a solution, so the

question is what to do with this information; how to layer on

additional, value-added preservation services. If format ID can be

provided as a discrete service, presumably it is possible to provide

other services as discrete components via Web services, perhaps from

multiple service providers.

We already have some clues as to the type of discrete preservation

services that might be provided (Figure 4). In addition a structure

that might lend itself to preservation Web services was emerging from

TNA's Seamless Flow programme (http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/electronicrecords/seamless_flow/default.htm).

TNA initiated this programme in an effort to reengineer workflow in the

creation, management and preservation of electronic records – demanded

by the

impact of increasing volume and the need to widen access (in this case

not in

response to open access but to meet freedom-of-information

requirements). One application of this approach was illustrated by

Brown (2005).

Applying this to Preserv led to the following structured process for

active

preservation aimed at repository content that enables the contributing

service

components to be identified:

- Characterisation: identification (as in PRONOM-ROAR), validation,

and property extraction

- Preservation planning: e.g. risk assessment (of generic risks

associated with particular formats/representation networks), technology

watch (monitoring technology change impacting on risk assessment),

impact assessment (impact of risks on specific IR content),

Preservation plan generation (to mitigate identified impacts, e.g.

migration pathways)

- Preservation action: e.g. migration (including validation of the

results) will provide ongoing preservation intervention to ensure

continued access or provide on demand preservation action, performing

migrations or supplying appropriate rendering tools at the point of

user access.

If we have repositories, growing content, services to access that

content and prospective preservation service providers, the one missing

component is a preservation services testbed, a scalable, realistic and

effective environment to test the tools and services. This might be

provided by the PLANETS

project (http://www.planets-project.eu/), an EU-wide project in which

both TNA and BL are partners.

Others

have described service-oriented

preservation architectures. PANIC

(Preservation webservices Architecture for Newmedia and Interactive

Collections) proposed a way of describing and discovering preservation

Web services using the Semantic Web (Hunter and Choudhury 2005). This

anticipates multiple services from multiple providers without

specifying what or who, and doesn't take account of possible market

mechanisms, which may become a key factor if services are to be

sustainable. Ferreira et al.

(2006) describe a preservation service

architecture that could in principle use a combination of service

providers and Web service agents, although providing little in the way

of evaluation to show

how effective this approach might be.

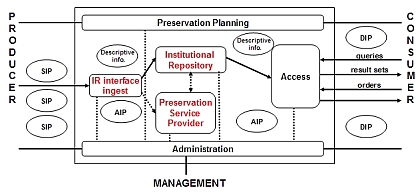

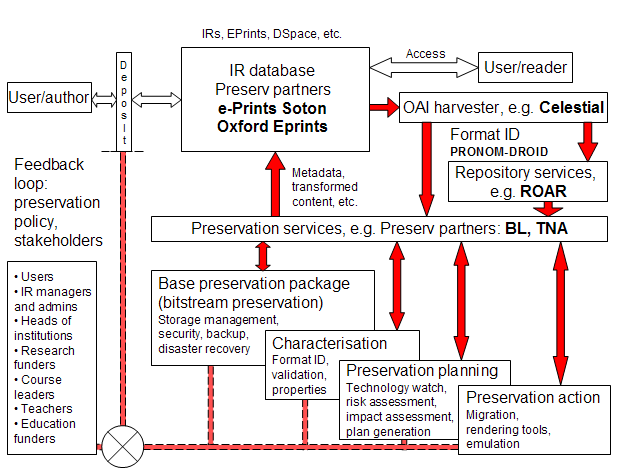

Based on experience with PRONOM-ROAR, and adopting ideas leading

towards distributed Web preservation services from Seamless Flow and

other projects, we have updated the service provider schematic from

Figure 3 to show repository services and selectable preservation

services (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Updated schematic of

Preserv service provider model showing distributed preservation services

Compared with Figure 3, the updated version displays the classified

preservation services identified above, with an additional bitstream,

or storage-based, preservation package. For simplicity these services

are shown with two-way interaction with, in principle, any number of

preservation service providers. The generic machine interface to the IR

is

replaced with an OAI harvester linked to a service with a

human-readable interface. This necessitates that the bi-directional

connecting arrow between the service provider and repository via the

machine interface reverts to an arrow in a single direction from

repository to

harvester. Completion of the feedback loop for the return of metadata

and transformed content to the repository from the services is

represented by a direct connecting arrow between the two. Critically,

PRONOM-DROID has moved from the repository user/author interface to

somewhere between harvester and interface repository services, as in

the case of PRONOM-ROAR.

The question is how will this schematic stand up to practical

examination? There is at least one example of one service in action, if

still experimental. Curtis (2006) describes the Automated Obsolescence

Notification System (AONS), a system to

analyse digital repositories and

determine whether any digital objects contained within them may be in

danger of becoming obsolescent. This is another application that uses

preservation information about

file formats taken from PRONOM. The approach is designed to work

primarily with DSpace repositories, although in general terms the work

is examining the interface between repository software and registries

such as PRONOM. In terms of the services outlined in Figure 5 this

comes closest to technology watch, part of preservation planning.

Conclusion

Distributed preservation

services require further investigation and raise further

questions about the interaction of services providers and client

repositories:

- What coordination is required between services?

- Which are the client-facing services and providers?

- What services can the market sustain?

While there may be some emerging consensus on the range of services

that

may be needed, the primary requirement is for market testing

conditions. The

market for repository

services is not well formed or structured. The number of repositories

is

growing internationally but these are at different stages of

development in

terms of content, institutional backing and funding and, therefore, in

policy. The market for preservation

services among IRs will be determined by repository

policy. A survey of repositories with a Preserv profile discovered

that none had a formal preservation policy (Hitchcock et al. 2007).

Preservation

policy should emerge naturally from general institutional and

repository

policy. OpenDOAR discovered that only one-third of repositories

have any kind of policy. This suggests that repositories may be waiting

for

clear guidance on preservation from trusted service providers, and this

allows

scope for the services proposed in this paper. It should not

be

assumed, however, that service providers have an entirely blank canvas

to work

with. The Preserv survey also revealed that, even without a policy,

repositories are making decisions with preservation consequences, for

example,

restrictions on file formats that could be deposited. Service providers

will

need to be aware of the practicalities facing repositories, including

prior

decisions, in scoping services.

The Preserv project has reached the end of its

period of funding, and may be able to continue with this work if the

project is extended. Even if not, the signs are that preservation

service

providers will emerge to take advantage of Web infrastructure to

deliver tailored and cost-effective services driven by increasing

awareness and need for preservation support by IRs.

References

Anderson, Richard, Hannah Frost, Nancy Hoebelheinrich, and Keith

Johnson (2005) The AIHT at Stanford University:

Automated Preservation Assessment of Heterogeneous Digital Collections, D-Lib Magazine,

Vol. 11, No.

12, December

http://www.dlib.org/dlib/december05/johnson/12johnson.html

Beagrie, Neil (2002) A Continuing Access and

Digital Preservation Strategy for the Joint Information Systems

Committee

(JISC) 2002-2005, JISC, 01 November

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/index.cfm?name=pres_continuing

Brown, A. (2005) Automating Preservation: New

Developments in the PRONOM Service, RLG

DigiNews, Vol. 9, No. 2, April 15, 2005 http://www.rlg.org/en/page.php?Page_ID=20571#article1

Chapman, S. (2003) Counting the Costs of Digital Preservation:

Is Repository

Storage

Affordable?

Journal of Digital Information,

Vol. 4 No. 2, May

http://jodi.ecs.soton.ac.uk/Articles/v04/i02/Chapman/

Cornell Tutorial (2003) The OAIS Reference Model,

section 4B in Digital

Preservation Management: Implementing Short-Term Strategies

for Long-Term Problems, Cornell University, September

http://www.library.cornell.edu/iris/tutorial/dpm/

Curtis, Joseph, AONS System Documentation, Australian

Partnership for Sustainable Repositories, The

Australian National University, Revision 169 2006-09-29, September 2006

http://www.apsr.edu.au/publications/aons_report.pdf

Day,

Michael (2003) Integrating metadata schema registries with digital

preservation systems to support interoperability.

2003 Dublin Core Conference,

Seattle, Washington, USA, 28 September - 2

October

http://www.ukoln.ac.uk/metadata/presentations/dc-2003/day/slides-draft.ppt

Declerck,

Luc and Chris Frymann (2004) DSpace / SRB Integration, CNI Fall Task

Force

Meeting, Portland, Oregon, December 6-7, 2004

http://libnet.ucsd.edu/nara/2004.12.07_CNI_NARA.ppt

Dempsey, Lorcan (2006) Networkflows, Lorcan

Dempsey's weblog, January 28

http://orweblog.oclc.org/archives/000933.html

DiLauro, Tim, Mark Patton, David Reynolds, and

G. Sayeed Choudhury (2005) The Archive Ingest

and

Handling Test: The Johns Hopkins University Report, D-Lib Magazine,

Vol. 11, No.

12, December

2005

http://www.dlib.org/dlib/december05/choudhury/12choudhury.html

Entlich, Richard

and Ellie Buckley (2006) Digging

Up

Bits of the Past: Hands-on With Obsolescence, RLG DigiNews, Volume 10, Number 5,

15 October 2006

http://www.rlg.org/en/page.php?Page_ID=20987#article1

EVIE (2006) Embedding a VRE in an

Institutional Environment (EVIE), Workpackage

4: VRE Preservation Requirements Analysis, to appear

http://www.leeds.ac.uk/evie/workpackages/wp4/EWD-24-WP4-PR01_v4.pdf

Ferreira, Miguel, Ana Alice

Baptista and José Carlos

Ramalho (2006) A Foundation for Automatic Digital Preservation, Ariadne, Issue 48, 30-July-2006

http://www.ariadne.ac.uk/issue48/ferreira-et-al/

Harnad, Stevan (2001) Re: Eprints Open Archive Software, posting

to American-Scientist-Open-Access-Forum, January 23

http://www.ecs.soton.ac.uk/~harnad/Hypermail/Amsci/1079.html

Heery, Rachel, and Sheila Anderson (2005) Digital Repositories Review,

UKOLN-AHDS, 19 February

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/uploaded_documents/digital-repositories-review-2005.pdf

Hitchcock, Steve, Tim

Brody, Jessie M.N. Hey and Leslie Carr (2007) Survey

of repository preservation policy and activity. Preserv project,

January 2007

http://preserv.eprints.org/papers/survey/survey-results.html

Hitchcock, Steve, Tim

Brody, Jessie M.N. Hey and Leslie Carr (2005) Preservation for

Institutional Repositories: practical and invisible. Ensuring Long-term

Preservation and Adding Value to Scientific and Technical data (PV

2005), Edinburgh, November 21-23

http://www.ukoln.ac.uk/events/pv-2005/pv-2005-final-papers/033.pdf

Hitchcock, Steve (2005) Capturing preservation metadata from

institutional repositories. DCC

Workshop on the Long-term

Curation within Digital Repositories, Cambridge, July 6

http://preserv.eprints.org/talks/hitchcock-dcccambridge060705.ppt

Hirtle, Peter (2001) OAI and OAIS: What's in a Name? D-Lib Magazine,

Vol. 7 No. 4, April

http://www.dlib.org/dlib/april01/04editorial.html

Hunter,

Jane, and Sharmin Choudhury (2005) Semi-Automated Preservation and

Archival of Scientific Data using Semantic Grid Services, Semantic Infrastructure for Grid Computing

Applications Workshop at the International

Symposium on Cluster Computing and the Grid, CCGrid 2005,

Cardiff, UK, May 2005

http://metadata.net/panic/Papers/SIGAW2005_paper.pdf

James, Hamish; Ruusalepp, Raivo; Anderson, Sheila; and Pinfield,

Stephen (2003) Feasibility and Requirements Study on Preservation of

E-Prints, JISC, October 29

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/uploaded_documents/e-prints_report_final.pdf

Knight, Gareth (2005) An OAIS compliant model for Disaggregated

services,

SHERPA-DP Report, version 1.1, 5/09/2005

http://ahds.ac.uk/about/projects/sherpa-dp/sherpa-dp-oais-report.pdf

Lewis, Stuart David, and Jon Bell (2006) Using OAI-PMH and METS for

exporting metadata and digital objects between repositories, CADAIR,

University of Wales Aberystwyth Institutional Repository, 2006

(announced 1 August 2006)

http://cadair.aber.ac.uk/dspace/handle/2160/203

also in Program: Electronic Library

and Information Systems, Vol. 40, No. 3, 2006, 268-276

Lynch, Clifford (2001)

Metadata Harvesting and the Open Archives Initiative. ARL Bimonthly

Report, No. 217, August http://www.arl.org/newsltr/217/mhp.html

Lyon, Liz, Heery,

Rachel, Duke, Monica, Coles, Simon J., Frey, Jeremy G., Hursthouse,

Michael B., Carr, Leslie A. and Gutteridge, Christopher J.

(2004)

eBank UK: linking research data, scholarly

communication and learning.

In All Hands Meeting 2004,

Nottingham, 31 Aug - 03 Sep 2004

http://eprints.soton.ac.uk/8183/

OAI (2001) Open Meeting, Washington DC, January 23

http://www.openarchives.org/meetings/DC2001/OpenMeeting.html

OAIS (2002) Reference

Model for an Open Archival Information System (OAIS),

Consultative Committee for Space Data Systems, CCSDS 650.0-B-1, Blue

Book, Issue 1, January, adopted as ISO 14721:2003

http://ssdoo.gsfc.nasa.gov/nost/wwwclassic/documents/pdf/CCSDS-650.0-B-1.pdf

RLG-OCLC (2002)

Trusted Digital Repositories:

Attributes and Responsibilities, An

RLG-OCLC Report, May

http://www.rlg.org/longterm/repositories.pdf

Rosenthal, David S. H., Thomas Lipkis, Thomas S. Robertson, and

Seth

Morabito (2005) Transparent Format Migration of Preserved Web Content, D-Lib Magazine, Vol. 11 No.

1, January

http://www.dlib.org/dlib/january05/rosenthal/01rosenthal.html

Santhanagopalan,

Kamini, Edward A. Fox and Gail McMillan (2006) A

Prototype for Preservation and Harvesting of International ETDs using

LOCKSS and OAI-PMH (pdf 36pp), 9th

International Symposium on Electronic Theses and Dissertations,

Quebec City, June 7 - 10, 2006

http://www6.bibl.ulaval.ca:8080/etd2006/pages/papers/SP10_%20Kamini_Santhanagopalan.pdf

Shirky, Clay (2005) AIHT: Conceptual Issues from Practical Tests, D-Lib Magazine,

Vol. 11, No.

12, December

http://www.dlib.org/dlib/december05/shirky/12shirky.html

Smith, Joan A., Martin Klein and Michael L. Nelson (2006)

Repository

Replication Using NNTP and SMTP, ArXiv, Computer Science,

cs.DL/0606008, v2, 2 Nov 2006

http://arxiv.org/abs/cs.DL/0606008

Steenbakkers, Johan F. (2004) Treasuring the Digital Records of

Science:

Archiving E-Journals at the Koninklijke Bibliotheek, RLG DigiNews,

Vol. 8, No. 2, April 15, 2004

http://www.rlg.org/en/page.php?Page_ID=17068&Printable=1&Article_ID=990

Suber, Peter (2007) Open access in 2006, SPARC Open Access Newsletter,

issue #105, January 2, 2007 http://www.earlham.edu/~peters/fos/newsletter/01-02-07.htm#2006

Suber, Peter (2006) Predictions for 2007, SPARC Open Access Newsletter,

issue #104, December 2, 2006 http://www.earlham.edu/~peters/fos/newsletter/12-02-06.htm#predictions

Van de Sompel, Herbert, and Carl Lagoze (2000) The Santa Fe

Convention of the Open Archives Initiative. D-Lib Magazine, Vol. 6 No.

2, February

http://www.dlib.org/dlib/february00/vandesompel-oai/02vandesompel-oai.html

Wilczek, Eliot and Kevin Glick (2006) Fedora

and the Preservation of University Records Project: Reports and

Findings, Tufts University and Yale University, Final Narrative Report

to National Historical Publications and Records Commission, September

27, 2006

http://dca.tufts.edu/features/nhprc/reports/index.html

Wollschlaeger,

Thomas (2006) ETD's

as pilot materials for long-term preservation efforts in kopal (pdf

8pp), 9th International Symposium on

Electronic Theses and Dissertations,

Quebec City, June 7 - 10, 2006

http://www6.bibl.ulaval.ca:8080/etd2006/pages/papers/SP10_Thomas_Wollschlaeger.pdf