Representing Technicians’ Work

Representing Technicians’ Work

I visited the Craft and Graft exhibition at the Crick Institute before it closure in early February 2020. To me, it read as part celebration, part careers pitch: it promoted the work that technicians do as vital and skilled, amidst a high-throughput, “Big Science” landscape. Yet I was particularly interested in its framing of (animal) technicians’ work as “craft”, with its implications of embodied, careful, and hands-on work. Below, I share some thoughts on how technicians’ work is represented in the exhibition, and reflect on what is foregrounded - and what is not - when representing animal care as a form of craft.

Craft & Graft celebrated the work of the varied technicians who work at the Institute. It was organised into five zones - about cell services, engineering, the fly facility, glass washing, and microscopy - comprising installations and some interactive opportunities. The exhibition provided a look at the work of the technicians “who perform incredible feats every day [in order to] make science happen”, demonstrating their essential role in making the Crick function even if “behind the scenes”. An edited excerpt of my notes illustrates how the scene was set for visitors entering the exhibition:

The first installation we come to is a video, entitled The Supply Chain. Scientists, we are told, are "not alone". Technicians are the ones who care for the material. Aesthetically, it foregrounds long panning shots of materials; no words, just sounds - techy, but also organic, such as boiling liquids. Diverse people move lots of glass around, wash things by hand, write down things, replenish them. Sometimes we are placed in the point of view of the technician: disembodied hands doing work (…). The scale is evident in the amount of equipment we see, and in the many gels being prepped at once with a robot. There is a sense of being part of a bigger whole as no person is ever seen doing something from beginning to end. The latter part of the video focuses on the progression of a precious vial of living cells that arrives to be studied. Firstly, they go into quarantine since, as the captions tell us, "all need to be given a clean bill of health" so they are checked for infection and that they are what was expected. Once in, technicians can "feed them, keep them warm and give them room to grow". "Now, thanks to input from teams of technicians, the scientist can start work". This is just one tiny fragment of science (…) all impossible without teams of technicians (…) and others "really make the Crick tick."

To me, this video showcased scientific work embedded on its underpinning socio-material infrastructure. It conveyed the institution as a seamless structure, emphasising flows of materials and people, and giving the sense of a collective approach to scientific work. At this scale (on big science projects in the biological sciences, see Vermeulen [2010]), no one works alone; the distribution of duties and expertise are the norm.

Within that world, technician’s labour appears to me as maintenance work: ensuring the continued supply and integrity of the whole. And maintenance work, although essential, is also easy to overlook – as Susan Leigh Star (1999) tells us, infrastructures require maintenance, but can often be hidden, except at moments of breakdown.

The type of maintenance work evident in these representations go beyond ensuring that supplies (eg glassware) are available, and show how technicians contribute to the quality control of the science taking place at the Crick by ensuring the continued survival of cell cultures and assuring the safety of inbound ‘raw materials’ for research. They are responsible for the assurance and care for all the things – from animals to cells, equipment to data - that make researchers’ work possible. Hence, in this landscape, technicians are a fundamental part of the “supply chain” that produces scientific knowledge.

Moving into the exhibition, technicians’ work (in their different iterations) was further illustrated as a highly professional, specialised job – and often requiring embodied, skilled practice. The work of Fly Facility staff is a good illustration here: another video, Many Hands, illustrated the precision, speed and skill required to insert DNA into fruit flies -

Staff in fly facility have "thousands of insect families in their care". The lab has several people at microscopes, who are completely surrounded by flasks with tags of different colours, topped with cotton wool. We are shown disembodied hands preparing fly embryos by creating an ordered row of white things, like grains of rice, using a small paintbrush. The narrator tells us that it needs to be done quickly, before embryos are one hour old, and that "it takes great skills to develop the fast pace, decisive movements, and steady hand required to do this”, but an "experienced technician" can do dozens in a sitting.

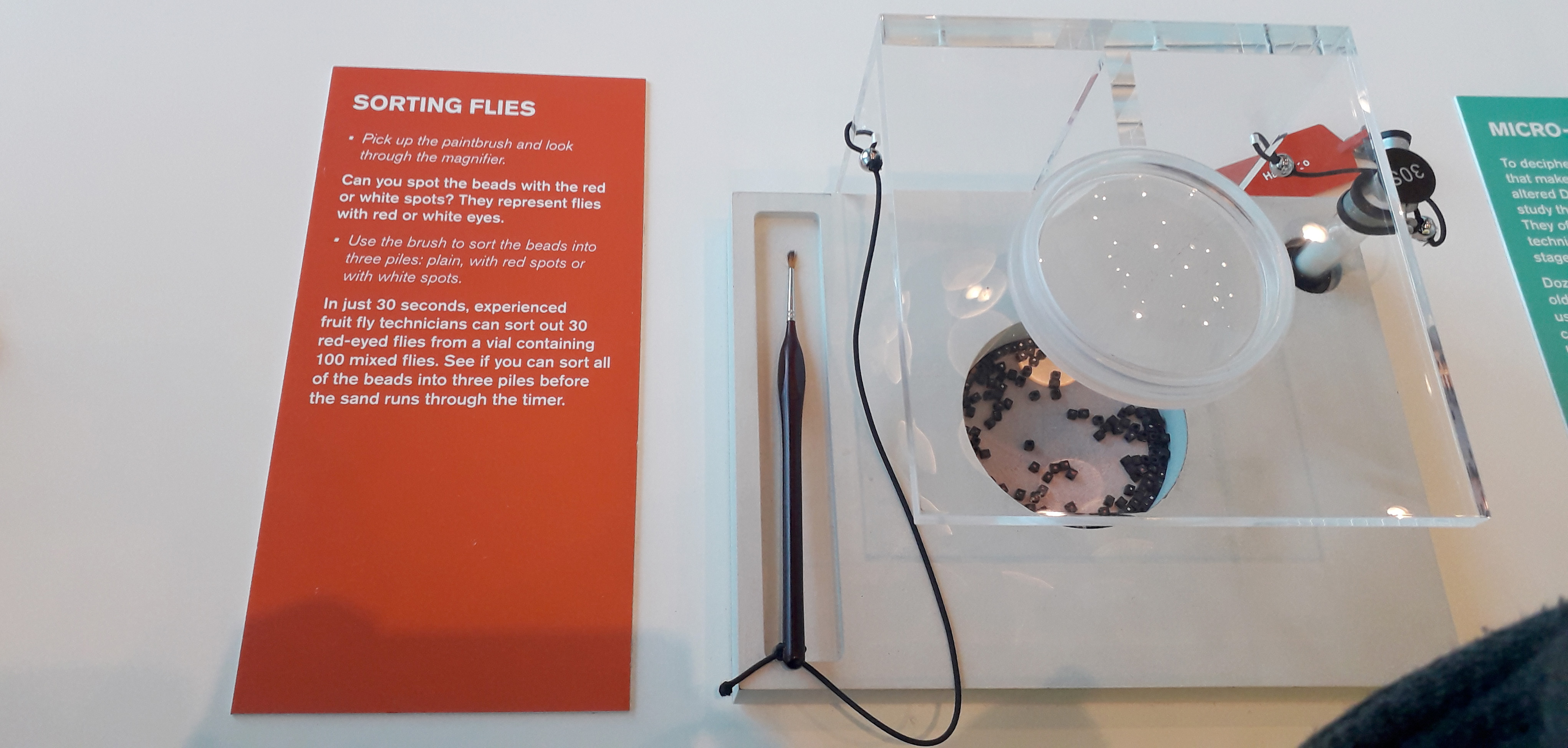

Indeed, experience is central to the definition of craft. In a dictionary, that term is described as “skill and experience, especially in relation to making objects; a job or activity that needs skill and experience, or something produced using skill and experience” . Doubtlessly, that connection between experience and developing craft is foregrounded in the exhibition. For instance, we are invited to try out the embodied skill of the fly facility staff by stepping up to a hands-on activity station. There, we can look at flies under the microscope, use a brush to move little cubes around a petri dish, and separate them according to their characteristics (in this case, a white or a red dot).In so doing we can engage in the same physical-material register, to feel something of the experience of being a technician.

Yet, if experience means practice, it has another sense as well: that of work which is experiential, that is, “[learned] from doing, seeing, or feeling things”. This is particularly apt in the case of animal technicians. As Beth and Emma have demonstrated in past work, to become an animal technician means developing the ability to read and interpret animals’ states of being by being attuned to, and knowledgeable of, animals’ movements and communications. It is “[t]his embodied expertise in somatic sensibilities (…) that enables a ‘good’ animal caretaker to know when something is wrong with an animal in their care” (Greenhough and Roe, 2011, p. 55) The shared experience of having a body is the precursor, on which technicians craft a very particular kind of expertise: that of knowing how to perceive with their own senses, and how to interpret what they see in order to make sense of the animal’s experience. Yet, this aspect was less visible in the representations of their work in the installation.

Images of animal care were not, on the whole, particularly prevalent in this installation. In addition to the fly facility work, images of zebrafish tanks and technicians appeared briefly in a video; but mice were noticeable for their absence, although they do have a virtual presence on the Crick’s website. With this relative absence come fewer opportunities to showcase the affective nature of the work done by technicians as they become experts in the care of laboratory animals.

Is this surprising? Perhaps not. How one might represent that encounter and that craft, in all its complexity, in the context of an exhibition is a considerable undertaking. Yet I wonder what it would look like if there was more space in this image for living, breathing animals and a recognition of the other kind of response-able work that animal technicians do every day. It might add another layer to these representations. On the one hand, it makes more explicit the lively relationships between humans and non-humans that happen within the landscape of the large research institution (and which, in turn, make science happen). On another, it could acknowledge the affective nature of the work done by technicians, recognizing also the emotional burden that accompanies the labour of care (Birke, Aluke and Michael, 2007; Davies, 2014). Doing so would be a way to celebrate the expertise and contribution of animal technicians as a unique form of craft.

Although now closed, it is still possible to see materials related to the exhibition online.

References

Birke, L., Arluke, A., & Michael, M. (2007). The sacrifice: How scientific experiments transform animals and people. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press.

Davies, K. (2014). Emotional Dissonance Among UK Animal Technologists: Evidence, Impact and Management Implications. PhD thesis, University of Plymouth.

Greenhough, B., & Roe, E. (2011). Ethics, space, and somatic sensibilities: Comparing relationships between scientific researchers and their human and animal experimental subjects. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 29, 47–66.

Star, S. L. (1999). The ethnography of infrastructure. American behavioral scientist, 43(3), 377-391.

Vermeulen, N. (2010). Supersizing science: On building large-scale research projects in biology. Universal-Publishers.