IS THE WORLD IN THE BRAIN, OR THE BRAIN IN

THE WORLD?

Max Velmans, Department of Psychology,

Goldsmiths, University of London, New Cross, London SE14 6NW.

Abstract: Lehar provides useful

insights into spatially extended phenomenology that may have major consequences

for neuroscience. However, Lehar’s

biological naturalism leads to counterintuitive conclusions and he does not

give an accurate account of preceding and competing work. This commentary compares Lehar’s analysis

with that of Velmans, which address similar issues but draws opposite

conclusions. Lehar argues that the phenomenal world is in the brain, and

concludes that the physical skull is beyond the phenomenal world. Velmans

argues that the brain is in the phenomenal world and concludes that the

physical skull is where it seems to be.

Is

the phenomenal world in the brain, or is the brain in the phenomenal world? As William James (1904) noted, the issue is

controversial. To decide, the observer

should

“... begin with a perceptual experience, the

'presentation', so called, of a physical object, his actual field of vision,

the room he sits in, with the book he is reading as its centre, and let him for

the present treat this complex object in the commonsense way as being 'really'

what it seems to be, namely, a collection of physical things cut out from an

environing world of other physical things with which these physical things have

actual or potential relations. Now at

the same time it is just those self-same things which his mind, as we say,

perceives, and the whole philosophy of perception from Democritus's time

downwards has been just one long wrangle over the paradox that what is

evidently one reality should be in two places at once, both in outer space and

in a person's mind. 'Representative' theories of perception[1]

avoid the logical paradox, but on the other hand they violate the reader's

sense of life which knows no intervening mental image but seems to see the room

and the book immediately just as they physically exist”.

James defended the former view, and consequently

developed a form of neutral monism, in which the phenomenal world can be

regarded as being either “mental” or “physical” depending on one’s interest

in it. If one is interested in how the

appearance of the perceived world depends on perceptual processing one can

think of it as mental (as a psychological effect of that processing). If one is

interested in how some aspect of the perceived world relates to other aspects

of that world (e.g. via causal laws) one can think of it as physical. Lehar, by contrast, defends

“biological naturalism” (a form of “physicalism”)—the view that the experienced

world is literally in the brain.

The difference is fundamental. But whatever view one takes about where to locate the perceived world, one fact is clear: the 3D world we see around our bodies that we normally think of as the “physical world” is part of conscious experience not apart from it. This perceived world is related to the unperceived world described by physics (in terms of quantum mechanics, relativity theory, etc.) but it is not identical to it. This is potentially paradigm shifting, for the reason that it redraws the boundaries of consciousness to include the perceived physical world, with consequences for our understanding of mind/body relationships, subjectivity versus objectivity, science, epistemology, and much else (see extensive discussions in Velmans, 1990, 1991a,b, 1993, 1996a, 2000a, 2001, 2002a,b). As Lehar notes in his target article, this conceptual shift also has consequences for neurophysiology. An accurate phenomenology of consciousness is a prerequisite for an adequate understanding of the neural processes that support that phenomenology. In this, Lehar’s gestalt bubble model provides an interesting, original and potentially useful step forward.

Given the fundamental nature of the issues, and the positive contributions of his paper, it is a pity that Lehar’s review of preceding and competing positions is often inaccurate and unnecessarily dismissive. For example, I barely recognised my own work on these problems from his summary. Lehar writes,

“Max Velmans (1990) revived an ancient notion of perception as something projecting out of the head into the world, as proposed by Empedocles and promoted by Malebranche. But Velmans refined this ancient notion with the critical realist proviso that nothing physical actually gets projected from the head; the only thing that is projected is conscious experience, a subjective quality that is undetectable externally by scientific means. But again, as with critical realism, the problem with this notion is that the sense-data that are experienced to exist do not exist in any true physical sense, and therefore the projected entity in Velman's theory is a spiritual entity to be believed in (for those who are so inclined) rather than anything knowable by, or demonstrable to, science. Velmans drew the analogy of a videotape recording that carries the information of a dynamic pictorial scene, expressed in a highly compressed and nonspatial representation, as patterns of magnetic fields on the tape.” Lehar then goes on to criticize this analogy, pointing out, for example, that “There is no resemblance or isomorphism between the magnetic tape and the images that it encodes, except for its information content.”

I do not revive Empedocles in Velmans (1990) and, as Lehar notes, I do not claim perception to be something physical projecting out of the head into the world. I argue that although information about the world is encoded inside the brain, the world appears to be outside the brain—a subjective effect that I call “perceptual projection.” Lehar agrees that this is how the world appears (I return to this below). While I accept that conscious experience is undetectable externally by scientific means (the “problem of other minds”), I also accept that it can be and is studied in science in many other ways that combine first- and third-person evidence (cf Velmans, 1996b, 2000b). I do not adopt sense-data theory, or treat conscious experience as a “spiritual entity to be believed in rather than anything knowable by science”. And in Velmans (1990) I make no mention of a videotape-TV screen analogy to illustrate “perceptual projection.” I use this analogy, elsewhere, e.g. in Velmans (1991a,b, 2000a, 2002a,b) to illustrate how identical information can be encoded in different formats, in support of a dual-aspect theory of information that Lehar also adopts. Lehar and I also agree that the phenomenal world must not be confused with the world-itself, e.g. as described by physics (indirect realism), that neural representations must be functionally sufficient to support the 3D phenomenal world, that the information encoded within its phenomenology must also be encoded in the brain, and that the differences between how the phenomenal world and the brain appear can be understood, at least in part, in terms of the same information being accessed or viewed from complementary first- and third-person perspectives (a dual-aspect theory of information). In short, one would not guess from his cursory summary, that apart from a few crucial differences, Lehar’s understanding of the consciousness/brain relationship in visual perception is virtually identical to my own.

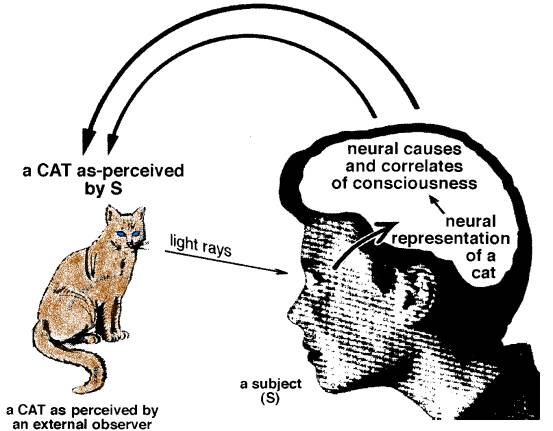

Figure 1. A reflexive model of visual perception

What are the crucial differences? Consider the simple model of visual perception shown in Figure 1. Viewed from the perspective of an external observer E, light rays reflected from an entity in the world (that E perceives to be a cat) innervate S’s eye and visual system. Neural representations of the entity, including the neural correlates of consciousness, are produced in S’s brain. In terms of what E can observe that is the end of the story. However, once the conditions for consciousness form in S’s brain, she also experiences a cat out in the world—so a full story of what is going on has to combine what E observes with what S experiences (see discussion of mixed-perspective explanations in Velmans 1996, 2000). If we combine E’s observations with those of S, an entity in the world (the initiating stimulus) once processed, is consciously experienced to be an entity in the world (a cat), making the entire process “reflexive.”

But here’s the puzzle: the neural

representations of the cat (observed by E) are undoubtedly in S’s brain

so how can S experience the cat to be outside her brain? The effect

is natural and ubiquitous, so there must be a natural explanation. Lehar’s

Gestalt bubble model gives some indications of what is achieved, but

doesn’t suggest how it is done—and at present, we just don’t know. However, both virtual reality and holography

might provide useful clues (Velmans 1993, 2000, Pribram, 1971, Revonsuo,

1995). Suppose, for example, that the information encoded in S’s brain is

formed into a kind of neural “projection hologram.” A projection hologram has the interesting property that the

three-dimensional image it encodes is perceived to be out in space, in front of its two-dimensional surface,

provided that it is viewed from an appropriate (frontal) perspective and it is

illuminated by an appropriate (frontal) source of light. Viewed from any other

perspective (from the side or from behind) the only information one can detect

about the image is in the complex interference patterns encoded on the

holographic plate. In analogous

fashion, the information in the neural “projection hologram” is displayed as a visual, three-dimensional object

out in space only when it is viewed from the appropriate, first-person

perspective of the perceiving subject.

And this happens only when the necessary and sufficient conditions for

consciousness are satisfied (when there is ‘illumination by an appropriate

source of light’). Viewed from any

other, external perspective the information in S’s ‘hologram’ appears to be

nothing more than neural representations in the brain (interference patterns on

the plate).

The “projection hologram” is, of course, only an analogy, but it is useful in

that it shares some of the apparently puzzling features of conscious

experiences. The information displayed in the three-dimensional holographic image is

encoded in two-dimensional patterns on a plate, but there is no sense in which the three-dimensional

image is itself “in the plate”. Likewise (contra Lehar), I suggest

that there is no sense in which the phenomenal cat observed by S is “in her

head or brain.” In fact, the 3D holographic image does not even exist (as an image) without an appropriately placed

observer and an appropriate source of light. Likewise, the existence of the

phenomenal cat requires the participation of S, the experiencing agent, and all

the conditions required for conscious experience (in her mind/brain) have to be

satisfied. Finally, a given holographic

image only exists for a given

observer, and can only be said to be located and extended where that observer perceives it to be[2]!

S’s phenomenal cat is similarly private and subjective. If she perceives it to be out in phenomenal

space beyond the body surface, then, from her perspective, it is out in phenomenal space beyond the

body surface.

But this doesn’t settle the matter. To decide whether the phenomenal cat is really outside S’s head we have to understand the relation of phenomenal space to physical space. Physical space is conceived of in various ways depending on the phenomena under consideration (for example as 4D space-time in relativity theory, or as 11 dimensional space in string theory). However, the physical space under consideration here, and in Lehar’s analysis, is simply measured space. Lehar agrees, for example, that at near distances phenomenal space models measured space quite well, while at far distances this correspondence breaks down (the universe is not really a dome around the earth). How do we judge how well phenomenal space corresponds to measured space? We measure the actual distance of an object within phenomenal space, using a standardised measuring instrument—at its simplest, a ruler, and count how often it has to be placed end to end to get to the object. Although rulers look shorter as their distance recedes, we know that their length does not significantly alter, and we conclude therefore that distant objects are really further than they seem.

Lehar and I agree (with Kant) that whether we are “subjects” or “external observers” we do not perceive things as they are in themselves—only phenomena that represent things themselves, and, together, such phenomena comprise our personal phenomenal worlds. In Figure 1, for example, the cat, the subject’s head, and the neural representations in S’s brain (as they appear to E) are as much part of E’s phenomenal world as the perceived cat is part of S’s phenomenal world. This applies equally to rulers or other instruments that E might use to measure distance. In sum, to carry out his science, E does not have an observer-free view of what is going on anymore than S does. E and S simply view what is going on from different third- and first-person perspectives. This has extensive consequences (worked out in Velmans, 2000a), but I only have space to comment on one of these here. According to Lehar, the 3D phenomenal world in my own analysis is “undetectable externally by scientific means”, does not “exist in any true physical sense” and is therefore “a spiritual entity to be believed in (for those who are so inclined) rather than anything knowable by, or demonstrable to, science.” Nothing could be further from the truth. Data in science consist entirely of observed phenomena that occur in a spatially extended phenomenal world, and the measurements that we make within that phenomenal world are the only ones we have on which to ground our science!

Where is this phenomenal world? Viewed from E’s perspective, it is outside his head, and the distance of the phenomenal objects within it can be measured, using standardised instruments that operate on phenomenal space (the distance of this phenomenal page from your eye for example can be measured with a ruler). Viewed from E’s perspective, the phenomenal world also appears to be represented (in a neural form) in S’s brain. Viewed from S’s perspective, things look the same: the phenomenal world appears to be outside her head, and, if she looks, a neural representation of that world appears to be encoded in E’s brain. Given that the evidence remains the same, irrespective of the perspective from which it is viewed, one can safely conclude (with James) that while a neural encoding of the world is within the brain, the phenomenal world is outside the brain. As this is how the natural world is formed, there must be a natural explanation (see above). In Velmans (2000a) I have shown how this analysis can be developed into a broad “reflexive monism” that is consistent with science and with common sense.

Now consider Lehar’s alternative: It is widely accepted that experiences cannot be seen in brains viewed from the outside, but Lehar insists that they can. Indeed, he insists that E knows more about S’s experience than S does and S knows more about E’s experience than E does, as the phenomenal world that S experiences outside her brain, is nothing more than the neural representation E can see inside her brain and vice-versa. This has the consequence that the real physical skull (as opposed to the phenomenal skull) exists beyond the phenomenal world. As Lehar notes, the former and the latter are logically equivalent.

Think about it! Stick your hands on your head. Is that the real physical skull that you feel or is that just a phenomenal skull inside your brain? If the phenomenal world “reflexively” models the physical world quite well at short distances (as I suggest), it is the real skull and its physical location and extension are more or less where they seem to be. If we live in an inside-out world as Lehar suggests, the skull that we feel outside our brain is actually inside our brain, and the real skull is outside the farthest reaches of the phenomenal world, beyond the dome of the sky. If so, we suffer from a mass delusion. Our real skulls are bigger than the experienced universe. Lehar admits that this possibility is “incredible.” I think it is absurd.

11. References

James, W (1904) Does 'consciousness' exist? Reprinted in: G. N. A. Vesey (ed) Body and mind: readings in philosophy. London: George Allen & Unwin,

1970, pp 202-208.

Pribram, K.H. (1971) Languages of the brain: experimental paradoxes and principles in

neuropsychology. New York: Brandon House.

Revonsuo, A. (1995) Consciousness, dreams, and

virtual realities. Philosophical Psychology, 8(1): 35-58.

Velmans, M (2003) Is the world in the brain, or the brain in the world? (Unabridged version of BBS commentary). URL to be supplied.

Velmans, M. (2002a) How could conscious

experiences affect brains? (Target Article for Special Issue) Journal of Consciousness Studies, 9 (11): 3-29.

URL to be supplied.

Velmans, M (2002b) Making sense of the causal

interactions between consciousness and brain (a reply to commentaries) Journal of Consciousness Studies, 9 (11): 69-95. URL to be supplied.

Velmans, M. (2001) A natural account of

phenomenal consciousness. Communication and Cognition,

34(1&2): 39-59.

http://cogprints.ecs.soton.ac.uk/archive/00001813/

Velmans, M. (2000a) Understanding Consciousness, London: Routledge/Psychology Press.

Velmans, M. (ed.) (2000b) Investigating Phenomenal Consciousness: New Methodologies and Maps,

Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Velmans, M. (1996a) Consciousness and the “causal

paradox.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences,

19(3): 537-542.

http://cogprints.ecs.soton.ac.uk/archive/00000596/

Velmans, M (ed) (1996b) The Science of Consciousness: Psychological, Neuropsychological and

Clinical Reviews. London: Routledge.

Velmans, M.(1993) A Reflexive Science of

consciousness. In Experimental and Theoretical Studies of Consciousness. CIBA Foundation

Symposium 174. Wiley, Chichester, pp 81-99.

http://cogprints.ecs.soton.ac.uk/archive/00000243/

Velmans, M. (1991a) Is human information

processing conscious? (Target Article) Behavioral

and Brain Sciences 14(4): 651-669.

http://cogprints.ecs.soton.ac.uk/archive/00000593/

Velmans, M. (1991b) Consciousness from a

first-person perspective. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 14(4):

702-726.

http://cogprints.ecs.soton.ac.uk/archive/00000594/

Velmans, M. (1990) Consciousness, brain, and the

physical world. Philosophical Psychology:

3, 77-99.

http://cogprints.ecs.soton.ac.uk/archive/00000238/