Aspects of Cognitive Poetics

This paper purports to be a short introduction to Cognitive

Poetics. After a short introductory section, it will

present some aspects of Cognitive Poetics, focussed

on a few brief case studies. A review of the twentieth-century

critical scene may reveal that there are, on the one

hand, impressionist critics who indulge in the effects

of literary texts, but have difficulties in relating

them to their structures. On the other hand, there

are analytic and structuralist critics who excel in

the description of the structure of literary texts,

but it is not always clear what the human significance

is of these texts, or how their perceived effects can

be accounted for. Cognitive Poetics, as I conceive

of it, offers cognitive theories that systematically

account for the relationship between the structure

of literary texts and their perceived effects. By the

same token, it discriminates which reported effects

may legitimately be related to the structures in question,

and which may not. By appealing to cognitive theories,

the critic ensures that the relating of perceived qualities

to literary structures is not arbitrary.

Thought processes are relatively convergent streams

of information that display specific directions, and

whose elements are well-defined, compact, tightly organised.

Emotional processes are relatively divergent streams

of information consisting of similar components, but

are more diffused in all respects, are less tightly

organised. So, rather than specific directions, they

display general tendencies. Cognitive poetics assumes

that poetic texts don't only have meanings or convey

thoughts, but also display emotional qualities perceived

by the reader. When you say "My sister is sad",

and "The music is sad", you use the word

"sad" in two different senses. In the first

sentence you refer to some mental process of a person.

In the second sentence you do not refer to a mental

process of the sound sequence, nor to a mental process

it arouses in you. One may be perfectly consistent

when saying: "That sad piece of music made me

happy". You refer to a perceptual quality generated

by the interaction of the particular melodic line,

rhythm, hamony and timbre of the music. In other words,

you report that you have detected some structural resemblance

between the sound patterns and emotions. When you say

"This poem is sad", you use the adjective

in the second sense. In this sense "sad"

becomes the aesthetic quality of the music or the poem.

The lines "chilling / And killing my Annabel Lee"

report a sad event, but their perceptual quality is

naive, childish, playful.1

When one considers the perceived qualities of poetry,

one cannot escape facing a rather disconcerting issue.

Words designate "compact" concepts; even

such words as "emotion" or "sadness"

are tags used to identify the mental processes, do

not convey the stream of information and its diffuse

structure. Notwithstanding, some poetry at least is

said to display diffuse emotions, vague moods, or varieties

of mystic experiences. Furthermore, language is a predominantly

sequential activity, of a conspicuously logical character,

typically associated with the left cerebral hemisphere;

whereas diffuse emotional processes are typically associated

with the right cerebral hemisphere (Ornstein, 1975:

67-68). Thus, while we can name emotions, language

does not appear to be well suited to convey their unique

diffuse character. Accordingly, emotional poetry, or

mystic poetry ought to be a contradiction in terms.

We know that this is not the case. But this presentation

of the problem emphasises that we have all too easily

accepted what ought not to be taken for granted. The

major part of this paper will discuss some ways poetry

has found to escape, in the linguistic medium, from

the tyranny of clear-cut conceptual categories. The

case studies to be presented will illustrate how emotional

qualities can be conveyed by poetry; and, as a more

extreme instance, how "altered states of consciousness"

are displayed by strings of words. One of the key-words

in this respect is "precategorial information";

or, perhaps, "verbal imitation of precategorial

information". Two additional key-words will be

"thing-free" and "gestalt-free".

Psychologists distinguish "rapid" and "delayed

categorisation". "Precategorial information"

is more accessible through the latter. It will be pointed

out that the reader's decision style may be decisive

here. Persons who are intolerant of uncertainty or

ambiguity may seek rapid categorisation and miss some

of the most crucial aesthetic qualities in poetry,

including emotional as well as grotesque qualities.

The last section of this paper will be devoted to the

cognitive foundations of poetic rhythm, and its empirical

study.

During the past sixty years or so, the word cognition

has changed its meaning. Originally, it distinguished

the rational from the emotional and impulsive aspect

of mental life. Now it is used to refer to all information-processing

activities of the brain, ranging from the analysis

of immediate stimuli to the organisation of subjective

experience. In contemporary terminology, cognition

includes such processes and phenomena as perception,

memory, attention, problem-solving, language, thinking,

and imagery. In the phrase Cognitive Poetics, the term

is used in the latter sense.

In the following characterisation of "poetics"

Bierwisch has recourse to both poetic structure and

perceived effects mentioned above:

The actual objects of poetics are the particular regularities that occur in literary texts and that determine the specific effects of poetry; in the final analysisthe human ability to produce poetic structures and understand their effectthat is, something which one might call poetic competence (Bierwisch, 1970: 98-99).2

Cognitive Poetics comes in precisely here: it offers

cognitive hypotheses to relate in a systematic way

"the specific effects of poetry" to "the

particular regularities that occur in literary texts".

I shall illustrate this in a moment, with relation

to a Hebrew and an English text. But first let us proceed

by mentioning a few central assumptions of Cognitive

Poetics.

One major assumption of cognitive poetics is that poetry

exploits, for aesthetic purposes, cognitive (including

linguistic) processes that were initially evolved for

non-aesthetic purposes, just as in evolving linguistic

ability, old cognitive and physiological mechanisms

were turned to new ends. Such an assumption is more

parsimonious than postulating independent aesthetic

and/or linguistic mechanisms. The reading of poetry

involves the modification (or, sometimes, the deformation)

of cognitive processes, and their adaptation for purposes

for which they were not originally "devised".

In certain extreme but central cases, this modification

may become "organised violence against cognitive

processes", to paraphrase the famous slogan of

Russian Formalism. Quite a few (but by no means all)

central poetic effects are the result of some drastic

interference with, or at least delay of, the regular

course of cognitive processes, and the exploitation

of its effects for aesthetic purposes. In this respect,

one should point out that emotions are efficient orientation

devices; and that much manneristic poetry is, precisely,

poetry of disorientation. The cognitive correlates

of poetic processes must be described, then, in three

respects: the normal cognitive processes; some kind

of modification or disturbance of these processes;

and their reorganisation according to different principles.

Poetry and Emotional Qualities

In the first section of this paper I claimed that language

is a highly differentiated logical tool by its very

nature, and that it requires special manipulations

to convey or evoke with its help lowly-differentiated,

diffuse emotional qualities. Cognitive Poetics investigates

a variety of ways in which poets overcome this problem.

One efficient means for this investigation is to apply

to poetry knowledge gained by psychologists concerning

the nature of emotions (cf. Tsur, 1978). When one attributes

some emotional quality to a text, he reports that he

has detected some significant structural resemblance

between the text and emotions. Thus, a brief discussion

of the structure of emotions in the present context

is inevitable. Psychologists have discerned the following

elements in emotions:

1. Cognitive situation appraisal ("cognitive",

in the first sense);

2. Deviation from normal energy level: increase (gladness,

anger), or decrease of energy (sadness, depression,

calm);

3. Diffuse information in a highly activated state that

is less differentiated than conceptual information;

4. Such information is active in "the back of one's

mind", without pre-empting everything else. To

play chess, for instance, you must know the possible

moves and strategies of the game; but you must also

want to win. This wish to win must be active in the

back of your mind, but may not usurp the place of your

thoughts on the moves and strategies.

Let us consider the first stanza of a short lyric poem by the great Hebrew poet Hayim Lensky (who wrote Hebrew poetry in Soviet Russia, and found his death in Stalin's concentration camps):

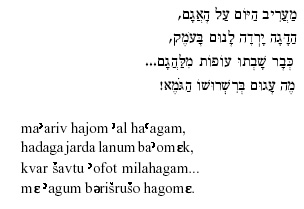

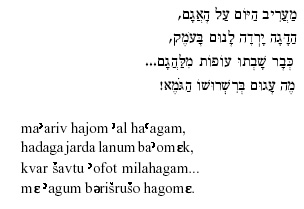

(1) The day is setting over the lake,We may make two preliminary observations about this stanza. First, it is only in the fourth line that it names an emotion ("sad"); in the first three lines it describes facts of the landscape that have no explicit emotional contents. In other words, the emotion appears to be there only by way of "telling", not "showing". Intuitively, however, this is not true, and we should attempt to account for this intuition in a systematic way. Second, the four descriptive sentences in the four lines relate to one another in two different ways: in one way, they refer to parts of the situation, complete one another to constitute the description of a whole landscape; in another way, they parallel one another in an important sense. The latter relationship is reinforced by the rhyme pattern.

The fish have gone down to sleep in the depth,

Birds have ceased from their chatter...

How sad is the rustling of the reeds!

The right side of the cortex processes its input more as a "patterned whole", that is, in a more simultaneous manner than does the left. This simultaneous processing is advantageous for the integration of diffuse inputs, such as for orienting oneself in space, when motor, kinesthetic and visual input must be quickly integrated. This mode of information-processing, too, would seem to underlie an "intuitive" rather than "intellectual" integration of complex entities (Ornstein, 1975: 95).In what I shall call below "delayed categorisation", the phrase "integration of diffuse inputs" undergoes a slight shift of emphasis, from "integration of diffuse inputs" to "integration of diffuse inputs". In the reading of landscape descriptions by way of "delayed categorisation", the more diffuse inputs too are perceived.

(2) A widow bird sate mourning for her loveWhat one notices in this short lyric is its exquisite musicality, and its intense emotional quality, its intense atmosphere. Yet, except for the first line, all the poem gives us merely a catalogue of physical facts, of what there is, or is not in the concrete reality presented. There are three barely noticeable, interrelated metaphors in the first line, if we assume that only human beings may have loves and become widows when they die, and mourn for them. However, the attribution of these notions to a bird is not very bold. The only other formal metaphor in the poem is crept on, in the sense of "moved on slowly"; this is not a very bold metaphor either. The rest of the poem contains plain, non-metaphorical language. By what means does, then, the poem generate the intense emotional atmosphere? Hardly by these metaphors alone.

Upon a wintry bough;

The frozen wind crept on above,

The freezing stream below.There was no leaf upon the forest bare,

No flower upon the ground,

And little motion in the air

Except the mill-wheel's sound.

Rapid and Delayed Categorisation

The shortest way to illustrate rapid and delayed categorisation

would be through what Hartvig Dahl called the "natural

experiment" of Helen Keller, who was deaf and

blind. She began to acquire the basic skills of communication

as late as at the age of six plus. Before that age,

she tells us in a less known book of hers, The World

I Live In (p. 117), she had no word for, e.g., ice

cream.

When I wanted anything I liked,ice cream, for instance, of which I was very fondI had a delicious taste on my tongue (which, by the way, I never have now), and in my hand I felt the turning of the freezer. I made the sign, and my mother knew I wanted ice cream. I "thought" and desired in my fingers (Dahl 1965: 537).

Later, after having acquired the word ice cream, the

peculiar sensation on her tongue and finger tips disappeared:

"the blind impetus, which had before driven me

hither and thither at the dictates of my sensations,

vanished forever" (Dahl 1965: 542).3

Most normal adults delay categorisation for fractions

of seconds, so as to gather information required for

making adequate judgments about reality. This is a

requirement for satisfactory adaptation. In Helen Keller's

case, categorisation was delayed for over six years;

and the story can demonstrate the advantages and disadvantages

of rapid and delayed categorisation. A category with

a verbal label constitutes a relatively small load

on one's cognitive system, and is easily manipulable;

on the other hand, it entails the loss of important

sensory information, that might be crucial for the

process of accurate adaptation (that is what I have

called above "compact concept"). Delayed

categorisation, by contrast, may load too much sensory

load on the human memory system; this overload may

be available for adaptive purposes and afford great

flexibility, but may be time-and-energy consuming,

and occupy too much mental processing space. Furthermore,

delayed categorisation may involve a period of uncertainty

that may be quite unpleasant, or even intolerable for

some individuals. Rapid categorisation, by contrast,

may involve the loss of vital information, and lead

to maladaptive strategies in life. In Helen Keller's

case, we see an opposition between a precategoric sensation

on her tongue, and a word. The former constitutes delayed,

the latter rapid categorisation. The diffuse sensations

are recoded into a compact, focussed concept, and labelled

with a verbal label.

Different categorisation strategies may generate different

poetic qualities. Different poetic texts may require

different categorisation strategies. In the instances

considered shortly, the particular poetic characteristics

of poetic passages is missed, if treated by way of

rapid categorisation; we have found, by contrast, that

the poetic potential of Omar Khayyam's Rubáiyáths

may not be fully realised by readers who are too tolerant

of delayed categorisation (cf. Tsur et al., 1990; 1991).

In what follows, I shall dwell on rapid and delayed

categorisation with reference to a variety of issues

related to poetry: understanding poetic metaphors,

the implied critic's decision style, and poetry and

altered states of consciousness.

Let us consider, first, an exquisite literary example.

In an undergraduate seminar on Alterman's poetry, I

isolated the following line from its context, and asked

the students to make any comments that seemed relevant

to them, without asking them any specific questions.

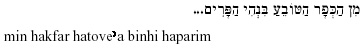

(3) From the village drowning in the moan of the oxenThe first responses received from the students represented the view that one may not refer to an isolated line, without relating it to its context. This is an academically approved, well-proven strategy of avoiding the need to experience elusive, "perceptual", poetic qualities, that cannot be subsumed under some clearly-defined, conceptual category. When I promised them that after discussing the peculiar qualities of the isolated verse line we shall examine it in its wider context, students began making such remarks as that the words drowning and moan have sinister connotations. This too is a well-proven strategy, with full academic backing, to avoid the direct experiencing of unevaluated and unclassified stimuli. So I asked the students "Does the image really evoke unpleasant, or sinister feelings?" The students were surprised to discover that the image was experienced as quite pleasant. The students had trouble in answering my question, how can we explain that a verse line in which two of the key terms have sinister connotations arouses pleasurable feelings. So I began a second round of disconcerting questions: "What do we feel when taking a warm bath?" Here it is more difficult to find academic legitimisation for avoiding immediate sensations. The first answer I received was "purification". This is an excellent example of shifting the focus of discussion from immediate, unevaluatedpossibly namelesssensations to some stable concept with a venerable spiritual history. The next answer was "wetness", which is tautological, and quite uninformative. Both answers are perfectly true, but involve a kind of "breaking the rules", reserved for cases in which it is difficult to find some respectable academic justification for evading the need to face elusive, nameless sensory experiences. Eventually, the following account began to emerge: There is an undifferentiated, diffuse sensation all over the outer surface of the skin, with an heightened feeling of unity of the various parts of the body, and a kind of harmony between the body and its immediate environment, even an abolition of the separateness of the body from its environment. This account was found acceptable by most seminar members.

Sensuous Metaphors and the Grotesque

Romantic poetry is a poetry of integration and orientation

that makes ample use of rich pre-categorial, or lowly-categorised

information. In the instances discussed in the preceding

section, an interference with the operation of the

orientation-mechanism was exploited for poetic effects.

This, however, is not necessarily the case in all poetry.

To show what I mean, let me begin with an extensive

discussion of two lines by the Hebrew poet Abraham

Shlonsky:

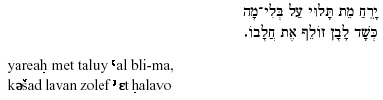

(4) A dead moon is hanging on nothingnessLet me begin, again, by reporting intuitions that some of my students had about these lines. In a seminar group, some of the students tended to interpret the "breast shedding its milk" as the embodiment of the principle of giving, of the life principle, having a contradictory relationship to the moon as "hung" and "dead" in the preceding line. The moon is associated here, paradoxically, with the principles of both life and death, with the principles both of passivity and of "giving". Running into difficulties, one of the students changed his interpretation and said that "shedding its milk" implies waste rather than feeding. All these interpretations, however, were incompatible with the intuitions of other participants in the seminar, including myself. Before going into a possible other interpretation, it should be noted that the above kind of interpretation is far from illegitimate. It relies on one of the most important principles of literary competence, formulated thus: "The primary convention is what might be called the rule of significance: read the poem as expressing a significant attitude to some problem concerning man and/or his relation to the universe" (Culler, 1975: 115). The interpretation is further corroborated by one of the fundamental aesthetic principles, viz., that good poetry is paradoxical, that is, it consists in the fusion of incompatible or discordant qualities. The "rule of significance", peculiar as it may seem from a literary point of view, is an operating instruction realising, in the literary domain, a principle that has much wider cultural applications. This principle is formulated by D'Andrade (1980) as follows: "In fusing fact and evaluational reactions, cultural schemata come to have a powerful directive impact as implicit values".

Like a white breast shedding its milk.

Most emotions involve an intuitive appraisal of a stimulus as good (beneficial) or bad (harmful). [...] It is very unlikely that organisms can unequivocally evaluate all stimuli with which they make contact. Some period, extended or brief, is necessary before tissue damage occurs, or internal injury develops, or pleasurable sensations occur. During this critical period of direct contact with an unevaluated object, a pattern of behavior apparently develops which, at the human level, is usually called surprise (Plutchik, 1968: 72).Sensuous metaphor may, then, be regarded as another literary device to delay the smooth cognitive process consisting in the contact with some unevaluated image; the device's function is thus to prolong a state of disorientation and so generate an aesthetic quality of surprise, startling, perplexity, astounding, or the like. 5 Thus, Shlonsky's simile generates, under the pretence of precise description, a perceived effect of startling, or even emotional disorientation. But the two lines contain additional devices of emotional disorientation, which will be discussed in the following.6

Decision Style

Our discussion of "Rapid and Delayed Categorisation",

and of "Sensuous Metaphors and the Grotesque"

may have suggested that readers may differ from one

another in their tolerance of delayed categorisation,

or of sensuous metaphors, or of the Grotesque. Such

differences in tolerance may affect their critical

decisions too. When confronted with a critical decision,

some readers or critics may prefer those options which

require less tolerance of delayed categorisation, or

of sensuous metaphors, or of the Grotesque; in short,

less tolerance of uncertainty or of emotional disorientation.

When in a piece of criticism, or in the output of a

critic, certain cognitive devices are consistently

deployed in a way that is characteristic of a certain

cognitive style, I call this "the implied critic's

decision style". Paraphrasing Booth (1961: 71-76)

on "the implied author", the implied critic

can be defined as the person whose decisions are reflected

in a given piece of criticism. "We infer him as

an ideal, literary, created version of the real man;

he is the sum of his choices" (74-75). Such differences

in decision style sometimes result in legitimate variant

readings; in some other instances, however, some readers

may display a tendency to avoid readings that exert

too much uncertainty or emotional ambivalence, and

prefer readings that appear less legitimate than the

avoided ones.

Poetry and Altered States of Consciousness

One of man's greatest achievements is personal consciousness.7

At a very early age he learns to construct

stable categories that make a stable world from streams

of sensory information that flood his senses. We have

already encountered the relative advantages and disadvantages

of rapid and delayed categorisation. Stable, well-organised

categories constitute a relatively easily manipulable

small load of information on one's cognitive system;

on the other hand, they entail the loss of important

sensory information that might be crucial for the process

of accurate adaptation. Exposure to fluid precategorial

information, by contrast, may load too much sensory

load on the human memory system; this overload may

be available for adaptive purposes and afford great

flexibility, but may be time-and-energy consuming,

and occupy too much mental processing space. Delayed

categorisation may involve a period of uncertainty

that may be quite unpleasant, or even intolerable for

some individuals. The solution to this catch appears

to be what Ehrenzweig (1970: 135) describes as "a

creative ego rhythm that swings between focussed Gestalt

and an oceanic undifferentiation".

The London psychoanalysts D.W. Winnicott and Marion Milner, have stressed the importance for a creative ego to be able to suspend the boundaries between self and not-self in order to become more at home in the world of reality where the objects and self are clearly held apart (ibid).Seen in this way, the oceanic experience of fusion, of a "return to the womb", represents the minimum content of all art; Freud saw in it only the basic religious experience. But it seems now that it belongs to all creativity (ibid).

In some people's responses to Alterman's metaphor in

quote 3 one may detect precisely such an element of

the suspension of boundaries between self and not-self,

of immersion in a thing-free and gestalt-free quality.

Altered states of consciousness are states in which

one is exposed for extended periods of time to precategorial,

or lowly-categorised information of varying sorts.

These would include a wide range of states in which

the actively organising mind is not in full control,

ranging from hypnagogic or hypnopompic states (the

semiconsiousness preceding sleep or waking respectively),

through hypnotic state, to varieties of religious experience,

most notably mystic and ecstatic experiences. In the

creative process, moments of "inspiration"

or of "insight" too may involve such altered

state of consciousness, though less readily recognised

as such.

Since much Romantic and Symbolist poetry on the one

hand and religious poetry of most styles on the other

seek to be exposed to rich precategorial information,

we might expect to find in these styles and genres

poems that seek to achieve, or to display some altered

state of consciousness as a regional quality.

"On Seeing the Elgin Marbles"

In what follows, I am going to discuss at some length

Keats;'s sonnet "On Seeing the Elgin Marbles".

(5) My spirit is too weekmortalityThis sonnet is quite remarkable in the poetry of altered states of consciousness. This is one of the exquisite instances in which Keats achieves one of his "many havens of intensity". This suggests a kind of "peak experience", similar to ecstasy; and it is, definitely, a prominent kind of "altered state of consciousness". In what follows I shall try to trace, briefly, the cumulative impact of elements that contribute to it. A unique feature of this poem is that it begins with a direct reference to a rather common kind of altered state of consciousness, "unwilling sleep", whether unwilling to come or to go.

Weighs heavily on me like unwilling sleep,

And each imagined pinnacle and steep

Of godlike hardship, tell me I must die

Like a sick Eagle looking at the sky.

Yet 'tis a gentle luxury to weep

That I have not the cloudy winds to keep

Fresh for the opening of the morning's eye.

Such dim-conceivèd glories of the brain

Bring round the heart an indescribable feud;

So do these wonders a most dizzy pain,

That mingles Grecian grandeur with the rude

Wasting of old Time with a billowy main

A sun a shadow of a magnitude.

Alternative Mental Performances

The perceived effect of a poem depends both on its structure

and the reader's mental performance of it. Alternative

performances of the same poem may yield different perceived

effects. In the following, I shall propose two alternative

mental performances of the poem's ensuing landscape

description. According to our foregoing assumption

concerning the relationship between landscape descriptions

and emotional qualities in poetry, one might expect

that the "pinnacles and steeps" amplify the

emotional quality of mortality, by increasing its diffuseness.

This, however, is not necessarily the case. Alternative

mental performances may be involved, and the reader

may switch back and forth between them. Horizontally,

"Each imagined pinnacle and steep" may be

conceived of as of part of an actual, continuous landscape;

vertically, as of strikingly representative examples

of "godlike hardship", that is, of a circumstance

in which excessive and painful effort of some kind

is required. Qua exemplary, the landscape tends to

bring the conceptual nature of hardship into sharp

focus. Now, the more emphasis

is placed on the actual (rather than the exemplary)

nature of the landscape, the softer (the more diffuse)

becomes the soft focus of perception of the abstraction

hardship. Alternatively, the more our awareness is

focused on the shapes of the "pinnacles and steeps",

the sharper the definition gets of the conceptual quality;

and, conversely, the more one's awareness is focussed

on locating oneself in space and time with reference

to the pinnacles and steeps, the more diffuse (the

more 'perceptual') the concept becomes. All this is

implied by our foregoing discussion of orientation.

The line "Like a sick eagle looking at the sky"

has a multiple relationship to the preceding utterance.

First, the eagle reinforces connotations of loftiness

in "pinnacles and steeps". Second, the eagle

enacts the sense of desperate helplessness; it combines

in one visual image impending death with what the eagle

might be in the sky, and thus reinforces a tragic feeling.

Third, the mere appearance of the eagle enhances the

suggestion that the "pinnacles and steeps"

may constitute an actual landscape. Fourth, the eagle

"looking at the sky" represents a consciousness

in the very act of locating itself with reference to

space, that is, it emphasizes the aspect of spatial

orientation, rather than the exemplary aspect in "each

pinnacle and steep", and thus increases the diffuse,

rather than the compact perception of mortality and,

also, of hardship.

Symbol and Allegory

Our discussion of the two aspects of "each imagined

pinnacle and steep" upon which awareness may be

focused, raises an additional issue of the utmost importance.

The theoretical equipment introduced here can help

to discern some crucial respects in which allegory

is distinguished from symbol. Traditionally, both suggest

a kind of 'double-talk': talking of some concrete entities

and implying some abstract ones. But whereas in allegory

the concrete or material forms are considered as the

"mere" guise of some well-defined abstract

or spiritual meaning, the symbol is conceived to have

an existence independent from the abstractions, and

to suggest, "somehow", the ineffable,

some reality, or quality, or feeling, that cannot be

expressed in ordinary, conceptual language. The

landscape in Keats's sonnet can be perceived as an

allegorical landscape, strikingly representative of

"godlike hardship", or as a symbolic landscape,

suggesting certain feelings that tend to elude words.

Now, ineffable experiences are ineffable precisely

because they are related to right-hemisphere brain

activities, in which information is diffuse, undifferentiated,

global, whereas the language which seeks to express

those experiences is a typical left-hemisphere brain-activity,

in which information is compact, well-differentiated,

and linear. Traditional allegory bestows well-differentiated

physical shapes and human actions upon clear-cut ideas,

which can be represented in clear, conceptual language

as well; by contrast, the symbol manipulates information

in such a way that some (or most) of it is perceived

as diffuse, undifferentiated, global. The symbol does

this by associating information with the cognitive

mechanism of spatial orientation, or by treating it

in terms of the least differentiated senses, or by

presenting its elements in multiple relationships

(cf. Tsur, 1987a: 1-4); all these techniques can be

reinforced by what I have called "divergent structures".

Keats and Marlowe

One might further highlight the peculiar semantic nature

of the present sonnet by comparing its lines 9-10 to

three lines from Marlowe;'s tragedy "Tamburlaine".

(6) Such dim-conceivèd glories of the brainIn spite of Tamburlaine's and Faustus' notorious craving for infinite things in Marlowe's tragedies, we may expect, from a common, sweeping generalization, Keats's poetry to be of a more romantic, more affective mood than Marlowe's poetry. It would be interesting to see whether and how the two passages bear out such pieces of "common knowledge".

Bring round the heart an indescribable feud ...(7) Nature that framed us of four elements,

Warring within our breasts for regiment,

Doth teach us all to have aspiring minds.

Ambiguity and Soft Focus

Presenting semantic elements in multiple relationships

is the favorite object of New Criticism's ambiguity-hunting.

Consider, for instance, "Such dim-conceivèd

glories of the brain". "Glory" is a

fairly clear-cut notion, denoting, for our purpose,

'exalted or adoring praise', or 'an object of pride',

or 'splendour, brilliance, halo'. "Glories of

the brain" may mean, accordingly, either 'adoring

glories given to the object of Greek Art' (the glories

of the onlooker's brain); or '"The Elgin Marbles"

are objects of pride, the glories of the creator's

brain'. "Dim" as a muting adjective brings

out the brilliance aspect of "glory". Thus,

again we have a sensuous presentation of the irrational

response: sight is the most differentiated of the senses,

hence serving conventionally as metaphor for rational

faculties. Though "dim" turns "glories",

implicitly, into light, it is "dim" that

makes the light less distinct, less differentiable.

Similarly, the "dim-conceivèd glories"

of the creator's brain stem from the dark layers of

the unconscious mind. Now consider "dim-conceivèd".

Which one of its possible meanings would be relevant

to the poem? "To conceive of" means 'To comprehend

through the intellect something not perceived through

the senses'. "To conceive" means 'to relate

ideas or feelings to one another in a pattern'; or,

in a different sense, 'to become pregnant' yielding

a fairly physical metaphor for irrational bringing

forth. At any rate, "dim" and "glories"

foreshadow, as it were, the more objectively presented

"sun" and "shadow" in the last

line. Thus, paraphrasing Arthur Mizener (1964: 142)

who, in turn, echoes Bergson on "metaphysical

intuition", no single meaning of these words will

these lines work out completely, nor will the language

allow any one of the several emergent figures to usurp

our attention. Thus, the blurred meanings contribute

to the diffuse perception of the sonnet. In cognitive

terms we might speak of overloading the cognitive system

with these rival meanings. In terms of figure-ground

relationship we might say that we handle the potentially

well-defined meanings by "dumping" them in

an undifferentiated "ground". The process

is very similar to that in the visual mode, where well-defined

shapes, when overlapping or endlessly repeated, are

perceived as undifferentiated ground.8

The adjective in "Of godlike hardship" means

'like, or befitting a god'; and it may suggest either

'hardship that only a god can endure', or 'hardship

that only a god can inflict'. In this way, the word

godlike fuses two plains of reality: that of the experiencing

subject, and of the external object. There is a similar

ambiguity in wonders in line 11, meaning either 'something

that causes astonishment, admiration, astonishment

or awe', or 'the emotion excited by what is strange,

admirable or surprising'. In such ambiguities (of which

there are quite a few in this sonnet) the various meanings

tend to blur each other, preventing each other from

usurping the entire available mental space. In my discussion

of "each imagined pinnacle and steep" I suggested

two alternative mental performances, a vertical and

a horizontal one: the former suggesting strikingly

representative examples of "godlike hardship",

the latter suggesting an actual, continuous landscape;

in the present context one might suggest a third kind

of mental performance, in which the various meanings

are simultaneously active, blurring each other and

preventing each other from usurping the whole available

mental space. That is how a soft, integrated focus

of meanings is achieved in this poem, underlying its

intense emotional quality.

I have described the synchronic effect of images hovering

between a subjective and an objective existence. They

have, however, a diachronic aspect too. The octet is

dominated by first person singular pronouns; they disappear

in the sestet all in all. Most conspicuous are the

impersonal constructs "glories of the brain"

and "round the heart", in stead of "glories

of my brain", and "round my heart".

Pain (in line 11) too is a psychological abstraction

which, again, seems to be unrelated to any individual

conciousness. The above ambiguous phrases serve as

transition from the "I", the enduring, conscious

element that knows experience to a less conscious state;

that is, they serve as transition from a state of

individual consciousness to an altered state of consciousness.9

In this state there is an awareness of

a stream of images, but no awareness of the self as

thinking, feeling, and willing, and distinguishing

itself from selves of others and from objects of its

thought. It concerns an "ability to make up one's

mind about nothingto let the mind be a thoroughfare

for all thoughts" (Keats, 1956: 26). This stream

of images, dissociated from the self as thinking, feeling,

and willing, and distinguishing itself from other selves

and from objects of its thought, leads to a state of

consciousness designated as "a most dizzy pain".

"Pain" merely names an acute but undifferentiated

feeling. While not diminishing the intensity of pain,

"dizzy" blurs its contours. "Dizzy"

refers to a whirling state of uneasy feeling, sometimes

extremely intense, blurring one's perception of the

external world. The very presence of "dizzy"

contributes to the structural resemblance of Keats's

poem to an altered state of consciousness. As Michael

A. Persinger says in his study of the neuropsychological

bases of God beliefs, "Few people appear to acknowledge

the role of vestibular sensations in the God Experience.

However, in light of the temporal lobe's role in the

sensation of balance and movement, these experiences

are expected. [...] Literature concerned with the God

Experiences are full of metaphors describing essential

vestibular inputs. Sensations of 'being lifted', 'feeling

light', or even 'spinning, like being intoxicated',

are common" (Persinger, 1987: 26).

The last tercet gives us the "chemical makeup"

of this "dizzy pain": it "mingles Grecian

grandeur with the rude wasting of old Time with a

billowy main a sun a shadow of a magnitude".

In this list the syntactic structure dissolves, reinforcing

a significant semantic aspect. In an attempt to understand

the poetic significance of this structure, let us quote

Bergson; on " metaphysical intuition;",

as quoted by Ehrenzweig who regards it as a gestalt-free

vision:

"When I direct my attention inward to contemplate my own self [...] I perceive at first, as a crust solidified at the surface, all the perceptions which come to it from the material world. These perceptions are clear, distinct, juxtaposed or juxtaposable one with another; they tend to group themselves into objects. [...] But if I draw myself in from the periphery towards the centre [...] I find an altogether different thing. There is beneath these sharply cut crystals and this frozen surface a continuous flux which is not comparable to any flux I have ever seen. There is a succession of states each of which announces that which follows and contains that which precedes it. In reality no one begins or ends, but all extend into each other" (Ehrenzweig, l965: 34-35).

In Keats's sonnet, the constitutents of the "dizzy

pain" are expressed by syntactically juxtaposed

phrases. You cannot escape juxtaposition in language;

but the dissolution of syntax relaxes its logical organisation.

Furthermore, the referents of those phrases are said

to be "mingled". In addition, with the exception

of "A sun", they don't "group themselves

into objects", into "sharply cut crystals

and [...] frozen surface"; all the rest are thing-free

and gestalt-free entities, which have no clear-cut

solid boundaries, so that they don't resist entering

the "succession of states" in which "no

one begins or ends, but all extend into each other".

The notorious 18th-century diction embodied in "billowy

main" has in this context a special effect. This

kind of diction makes use, as Wimsatt (1954) pointed

out, of a general term as "main" (in the

sense of 'broad expanse') with an epithet denoting

one of its concrete attributes, "billowy",

skipping the straightforward term on the "substantive

level", "ocean" or "high sea",

generating tension between the more than usually abstract

and the more than usually concrete. Both terms of the

phrase designate gestalt-free entities, and in the

present context suggest enormous energy.

Grandeur and magnitude are etymologically synonymous.

Nonetheless, they have acquired different senses: the

former applies to the impressive, the latter to the

measurable qualities of things (in this sense, too,

the sonnet moves from the subjective towards the more

objective). Their sublime effect is cumulative. The

sun and the shadow are clear opposites fit for a forceful

ending of a sonnet dominated by indistinctthough sublimepassions.

Nonetheless, "a shadow of a magnitude" intimates

some essence beyond the perceptible realm. Both shadow

and magnitude are attributes of physical objects. The

shadow is but a reflection of an object; magnitude

is an abstraction from an object; the "object"

itself, which remains unnamed, has been skippedgenerating

high metaphoric tension between both sides of the omitted

"substantive level". The magnitude is here

a thing-free abstractioncasting a visible shadow; and

here we have the sun that gives the lightto make the

shadow-casting more real. Does this not suggest, even

make us visualise, so to speak, a most intense, supersensuous

reality beyond the "cave" we are bound to

live in?

Thus, Keats's sonnet begins with a rather trivial kind

of altered state of consciousness, suggested by the

low-differentiated predicate "weighs" applied

to the abstract subject "mortality" on the

one hand, and the hypnagogic state "unwilling

sleep" on the other hand. It moves through successions

of sublime entities beginning with a concrete landscape

and culminating in a most intense low-differentiated,

diffuse "peak experience" affording an insight

into an imperceptible world "beyond". The

peculiar rhyme-structure of the sestet in this sonnet

makes a unique contribution to this diffuse "open"

ending. The so-called Italian Sonnet may have a variety

of rhyme-patterns in its sestet; in this sonnet the

rhyme pattern is: ababab. Suppose the poem ended with

an abab quatrain, say

(8) Such dim-conceivèd glories of the brainIrrespective of the illogical linking of the last line to the preceding ones, such a structure generates a symmetrical, stable ending. The fourth line of the unit constitutes a highly required closure. Now when you have not four but six lines, in an ababab pattern, in stead of a stable closure, you obtain a fluid pattern. The fluidity of this pattern is further heightened by the tense enjambment "with the rude / Wasting of old Time". If the closed ending of excerpt (8) has a highly-differentiated symmetrical shape, inducing a rational perceptual quality, the open ending of excerpt (5) has a fluid, lowly-differentiated, diffuse quality, reinforcing the lowly-differentiated, diffuse state of consciousness indicated at the semantic and thematic level of the sonnet.

Bring round the heart an indescribable feud;

So do these wonders a most dizzy pain,

A sun a shadow of a magnitude.

(9) ...then on the shore

Of the wide world I stand alone and think

Till Love and Fame to nothingness do sink.

(Keats, "When I have fears")

(10) Still, still to hear her tender-taken breath,According to Barbara Herrnstein-Smith (1968: 172-182), the mention of death or nothingness at the end of such a poem constitutes a "closural allusion", arousing a vague feeling that there is nothing after this. The couplet following the quatrains reinforces this feeling of closure. Thus, in these sonnets, the mention of death (coupled with intense passion) generates a feeling of ecstasy, or "peak experience"; this feeling of "peak" is reinforced by the structural closure of the couplet, generating a conclusive tone. In Keats's Elgin-Marbles sonnet, by contrast, there is no such mention of death, or structural closure. On the contrary rather, the ababab rhyme-pattern commits a "sabotage" against the symmetrical abab grouping. The ab unit has different perceptual functions in the two structures. In the abab grouping, the redoubling of this unit generates a symmetrical closed shape, in which the fourth line is highly required, achieving a strong closure. In the ababab rhyme-pattern the ab pair of lines is perceived as an endlessly repeatable unit, generating an open, fluid ending. At the same time, the run-on line toward the end commits another "sabotage", against the two-line groupings of ab. Furthermore, while the juxtaposed phrases divide the last but one line into two symmetrical halves, 5 + 5, the last line is divided into two assymmetrical parts, 2 + 8yet another "sabotage" against closure. In this way, in spite of the rigorous rhyme pattern, there is here a feeling of dissolving shapes reinforcing any impression of dissolving consciousness suggested by the contents and the semantic structure. The possible Platonic allusion in "a shadow of a magnitude" suggests the possibility of having caught some vague knowledge of some world inaccessible to the senses.

And so live everor else swoon to death.

(Keats, "Bright Star")(11) Love, Fame and Beauty are intense indeed,

But death intenser; Death is Life's high meed.

(Keats, "Why did I laugh?")

Metre and Rhythm

The Empirical Dilemma

In the foregoing discussion we have observed how cognitive

processes shape and constrain poetic form, the reader's

response, and the critic's decisions. In this last

section of my paper I will explore, very briefly, how

cognitive processes shape and constrain poetic rhythm,

and the rhythmical performance of poetry. In what follows,

I will present, in a nutshell, a cognitive conception

of poetic rhythm, as well as some of the major problems

related to its empirical study (elsewhere presented

at great length, e.g., Tsur 1977; 1998).

An iambic pentameter line is supposed to consist of

regularly alternating unstressed and stressed syllables.

In the first one hundred sixty five lines of Paradise

Lost there are only two such lines (Tsur, 1998: 24).

How do experienced readers of poetry recognize vastly

different irregular stress patterns as iambic pentameter?

Since the early nineteen-twenties there has been instrumental

research of poetry, in an attempt to discover some

regularity. The greatest achievement of these researchers

was that they refuted an obstinately persistent myth

that there are equal or proportional time intervals

between stressed syllables or regions of stress. But

they had a naive conception of poetic rhythm: they

thought they were measuring relationships that constitue

the rhythm of a poem, whereas they were measuring some

accidental performance of it.10

To avoid this problem, Wellek and Warren (1956, Chapter

13) proposed a model, according to which poetic rhythm

has three "dimensions": an abstract versification

pattern that consists of verse lines and regularly

alternating weak and strong positions; a linguistic

pattern that consists of syntactic units and irregularly

alternating stressed and unstressed syllables; and

a pattern of performance. Based on this model, I developed

a perception-oriented theory of metre, including a

theory of rhythmical performance, based on speech research,

the limited-channel-capacity hypothesis, and gestalt

theory. The rhythmical performance of poetry (just

as the understanding of a metaphor) is a problem-solving

activity: when the linguistic and versification patterns

conflict, they are accommodated in a pattern of performance,

such that both are perceptible simultaneously. The

versification pattern exists only in the cognitive

system as a "metrical set": as an expectation,

or a memory trace in short-term memory. Since according

to George Miller (1970) channel-capacity is rigidly

limited at the "magical number seven plus or minus

two", the vocal material must be manipulated such

as to save mental processing space for the simultaneous

perception of the conflicting patterns. When I wanted

to test this theory empirically, all the great gurus

of instrumental phonetics told me hat this was impossible,

because the major part of poetic rhythm takes place

in the mind, and only a small part of it is detectable

in the vocal output. I decided to sidestep this problem

by making certain predictions based on my theory as

to the vocal manipulations required, and see whether

performance instances judged rhythmical conform with

these predictions. I made predictions in terms of relative

stress, clear-cut articulation, gestalt grouping, and

certain (musical) pitch-intervals. However, again,

I was told by all the great gurus that none of these

variables can be read off from the machine's output.

It took me over twenty five years to find a way to

reformulate my research questions in terms that the

machine could understand. These terms included continuity

and discontinuity. My 1977 hypothesis was that conflicting

patterns could be indicated by conflicting vocal cues

(Tsur, 1977: 97, 103, 134). The break-through occurred

when I found a way to treat a wide range of conflicting

phenomena in terms of simultaneous continuity and discontinuity.11

These

conflicting phenomena included run-on sentences, strings

of consecutive stressed syllables, and even stress

maximum in a weak position. Here I will be concerned

only with the first of these phenomena.

Conflicting Prosodic Patterns: An Empirical Research

Poetic Rhythm consists, then, of three concurrent patterns:

versification pattern, linguistic pattern and performance.

Where the first two conflict, performance must offer

an "elegant solution" to the problem. In

a rhythmical performance, the conflicting linguistic

and versification patterns are simultaneously perceptible.

Enjambment consists in such a conflict: the line ending

demands discontinuation in the flow of speech, the

sentence running on from one line to the other requires

continuation. The received view (formulated by Chatman)

denies the possibility of a solution to such a problem:

in performance, all ambiguities have to be resolved before or during delivery. Since the nature of performance is linear and temporal, sentences can only be read aloud once and must be given a specific intonational pattern. Hence in performance, the performer is forced to choose between alternative intonational patterns and their associated meanings (the "Performance" entry of The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics, 1993: 893; cf. Chatman, 1965; 1966).

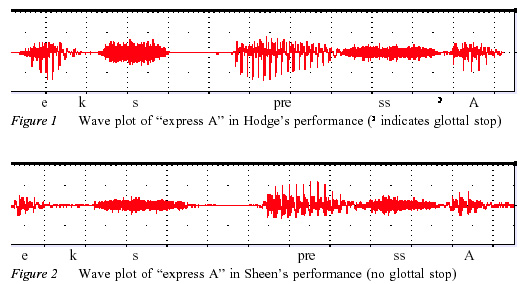

I beg to differ on this matter. In my 1977 book I speculated that conflicting patterns can be indicated by conflicting vocal cues. In my 1998 book I demonstrated this in an instrumental research. Consider the following verse instance from Keats's "Ode on a Grecian Urn" in which the versification unit (the verse line) conflicts with the syntactic unit (the clause), that is, when the phrase or clause runs on from one line to the next one. Let us compare two recordings by two leading British actors, Douglas Hodge and Michael Sheen.

12. Sylvan historian, who canst thus express

A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme...

Listen to two actors' readings of quote 12 (Douglas Hodge and Michael Sheen).

| Hodge | Sheen |

| published version | manipulated version |

.13

| published version | first alternative version | second alternative version |

References

This page was created using TextToHTML. TextToHTML is a free software for Macintosh and is (c) 1995,1996 by Kris Coppieters