Niels Lepperhoff (2002)

SAM - Simulation of Computer-mediated Negotiations

Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation

vol. 5, no. 4

To cite articles published in the Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, please reference the above information and include paragraph numbers if necessary

<http://jasss.soc.surrey.ac.uk/5/4/2.html>

Received: 22-Apr-2002 Accepted: 20-Sep-2002 Published: 31-Oct-2002

Abstract

Abstract The SAM Model

The SAM ModelBeta: I prefer ############111#0#0# (4)

Delta: I propose 23

Alpha: I prefer ##1###########11###0 (21)

Gamma: I agree with 21

|

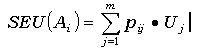

| Equation 1 |

|

| Figure 1. Sketch of the action selection of agent A and perception of agents B and C |

Validation

Validation

Investigation Methods

Investigation Methods

|

| Equation 2 |

To calculate time take T the number of negotiations including repeats (a), the number of cells (b), and the maximum of possible repeats (c) are taken into consideration:

|

| Equation 3 |

|

| Equation 4 |

|

| Equation 5 |

Results

Results

|

| Figure 2. Changes in negotiation quality depending on whether a negotiation has to begin with a proposal. |

|

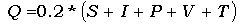

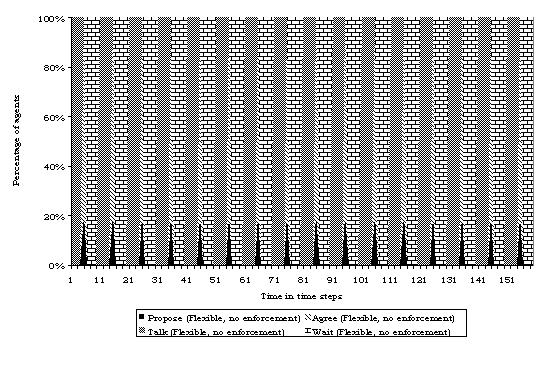

| Figure 3. Agents' activities over time of the "Flexible" group. The first run with a forced start with a proposal is shown. The values indicate which proportion of agents carried out a specific action at a time step. Time steps of counting votes are omitted.[1] |

|

| Figure 4. Agents' activities over time of the "Flexible" group. The first run without a forced start with a proposal is shown. The values indicate which proportion of agents carried out a specific action at a time step. Time steps of counting votes are omitted. |

|

| Figure 5.Change of negotiation quality with different sizes of agents' ideas |

|

| Figure 6. Negotiation quality for four and 16 cells |

|

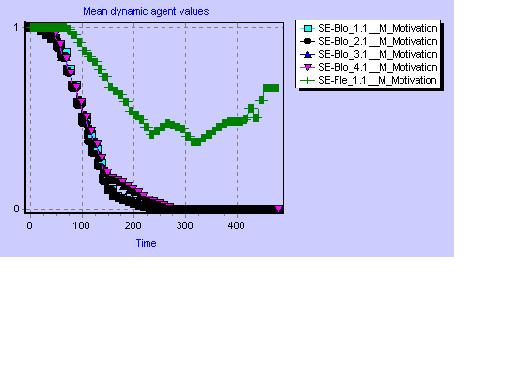

| Figure 7. Change of the mean motivation in the "block" scenario group with 16 cells. The upper curve belongs to "SE-Fle_1.1". |

|

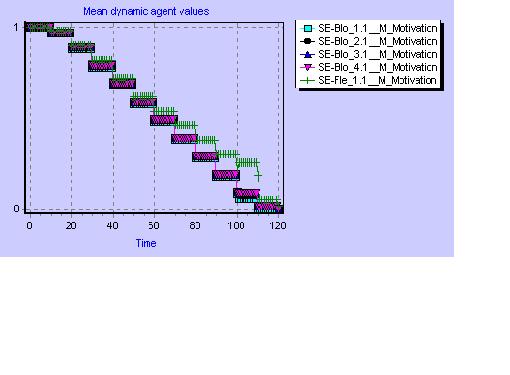

| Figure 8. Change of the mean motivation in the "block" scenario group with four cells. The upper curve belongs to "SE-Fle_1.1". |

|

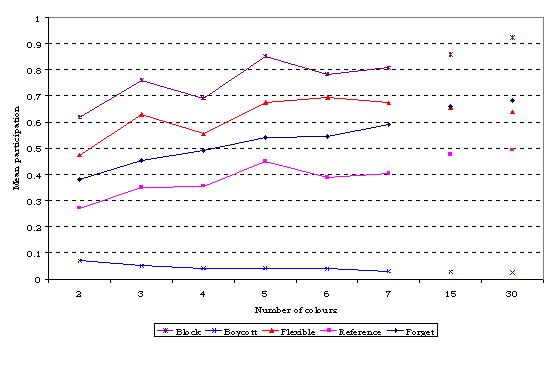

| Figure 9. Negotiation quality for different numbers of colours |

| Number of colours | Block | Boycott | Flexible | Reference | Forget |

| 2 | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| 3 | 0.9375 (-) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (-) | 0.9750 (0.0323) |

| 4 | 1 (-) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 0.9375 (-) | 1 (0) |

| 5 | 0.8750 (0) | 1 (0) | 0.9875 (0.0264) | 0.9375 (-) | 0.9938 (0.0198) |

| 6 | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 0.9688 (0.0329) | 1 (0) | 0.9938 (0.0198) |

| 7 | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 0.9875 (0.0395) | 1 (0) | 0.9938 (0.0198) |

| 15 | 0.9063 (0.0442) | 1 (0) | 0.9812 (0.0422) | 0.9375 (-) | 1 (0) |

| 30 | 0.8750 (0.0625) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (-) | 0.9750 (0.0323) |

|

| Figure 10. Mean participation with different numbers of colours |

|

| Figure 11. Change of negotiation quality with different sizes of tolerance interval |

|

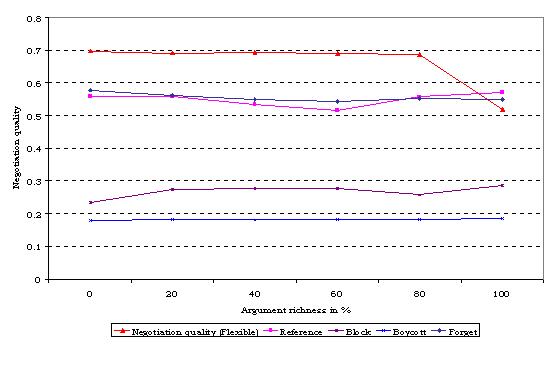

| Figure 12. Change of the negotiation quality for different values of the parameter "argument richness". |

| Argument richness | Negotiation quality | Standard deviation | Runs (N) |

| 0 | 0.5581 | 0.0042 | 2 |

| 20 | 0.5710 | 0.0062 | 3 |

| 40 | 0.5646 | 0.0213 | 4 |

| 60 | 0.5480 | 0.0196 | 3 |

| 80 | 0.5568 | 0.0003 | 2 |

| 100 | 0.5935 | 0.0087 | 3 |

|

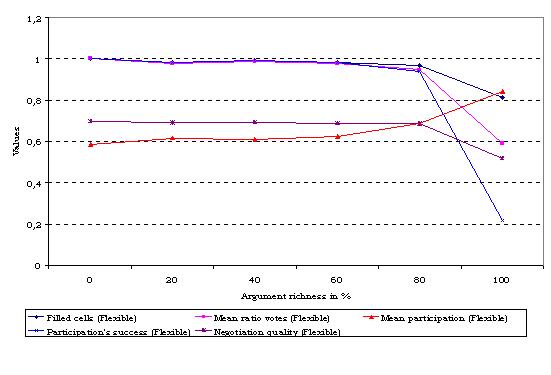

| Figure 13. In-depth analyse of scenario group "flexible". |

|

| Figure 14. Change of negotiation quality in all five scenario groups with different argument richness and a negotiation duration of four time steps. |

|

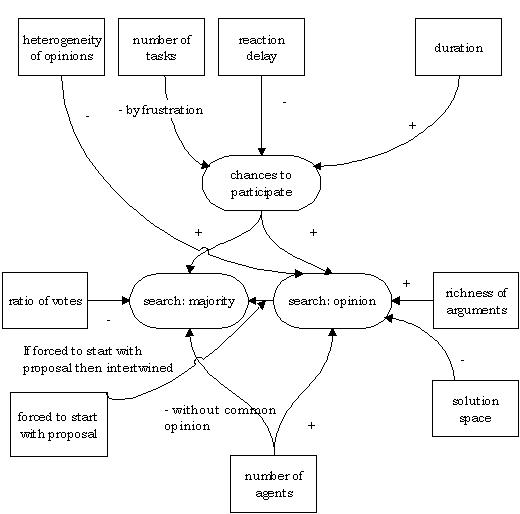

| Figure 15. How parameters influence the search for a common opinion and the search for a majority. "+" indicates supporting and "-" weakening relations. |

Discussion

Discussion

|

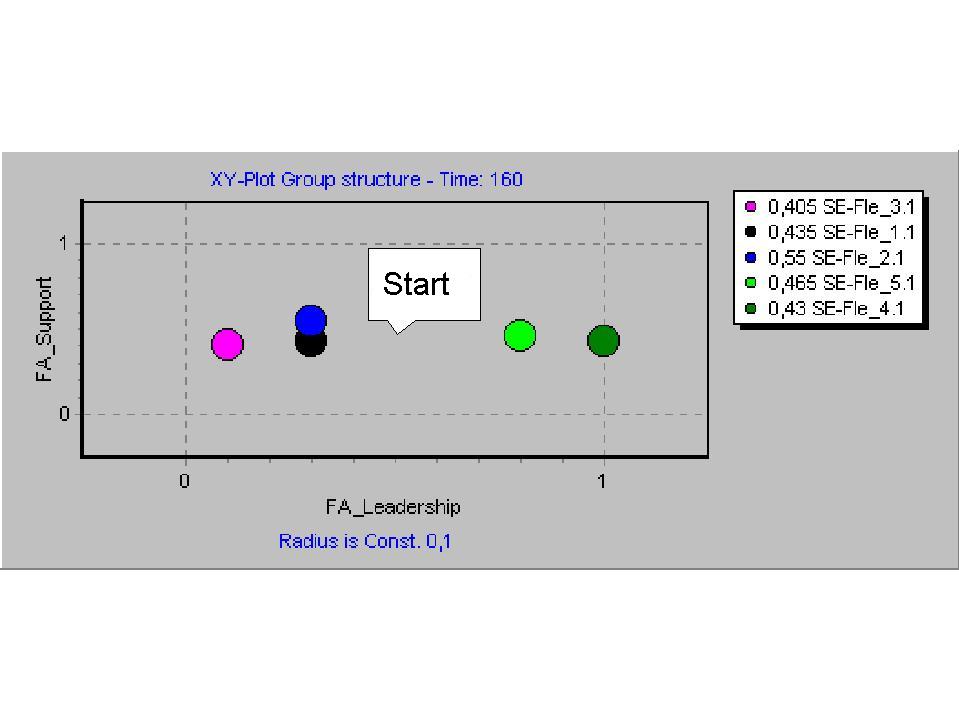

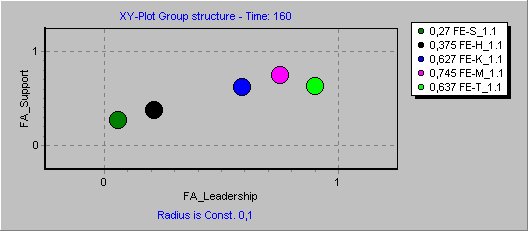

| Figure 16. Representation of the group structure in the dimensions of leadership and support at the end of the first run of the reference scenario for the "Flexible" group. Agents start at the point (0.5, 0.5). The points shown are means of agents' leadership and support values towards the named agent. |

|

| Figure 17. Representation of the group structure in the dimensions of leadership and support at the end of the first run of the reference scenario for the "Reference" group. The upper diagram shows the group structure at the beginning and the lower diagram at the end of the negotiation. |

Conclusion

Conclusion

2 To understand the following line of argument it is important to remember that the correspondence between the parameter values and the common interpretation of "richness" is counterintuitive!

3 The term "actor" refers to the sociological model of a human. In contrast the term "agent" means a computerized model of an actor.

4 This finding sounds trivial. In laboratory and field experiments persons' opinions are hard to measure, which is why the participants' opinions play only a minor role in the scientific discussion.

5 The SAM model focuses on task-oriented behaviour thus emotional leaders - or other kinds of leader - are not represented.

BECKER-BECK U (1997), Soziale Interaktion in Gruppen. Struktur- und Prozeßanalyse. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.

BOOS M (1996), Entscheidungsfindung in Gruppen. Eine Prozeßanalyse. Bern: Verlag Hans Huber.

BRUNNER E J, TSCHACHER W (1991), Distanzregulierung und Gruppenstruktur beim Prozeß der Gruppenentwicklung. I.: Theoretische Grundlagen und methodische überlegungen. Zeitschrift für Sozialpsychologie, Vol. 22, No. 2. pp. 87-101.

DEFFUANT G, NEAU D, AMBLARD F, WEISBUCH G (2000), Mixing beliefs among interacting agents. in: Ballot G, Weisbuch G, (eds.), Applications of Simulation to Social Sciences. Oxford: Hermes.

DÖRING N (1999), Sozialpsychologie des Internets. Die Bedeutung des Internets für Kommunikationsprozesse, Identitäten, soziale Beziehungen und Gruppen. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

FREY S, BENTE G, FRENZ H-G (1995), Analyse von Interaktionen. In Schuler H (Eds.), Organisationspsychologie, 2nd edition. Bern et al.: Verlag Hans Huber.

GILBERT N, TROITZSCH K G (1999), Simulation for the Social Scientist. Buckingham et al.: Open University Press.

GIRGENSOHN-MARCHAND B (1994), Ergebnisse der empirischen Kleingruppenforschung. In Schäfers B (Eds.), Einführung in die Gruppensoziologie. Heidelberg: Quelle & Meyer.

HEIL A H (1997), Inhouse-Kommunikation über Electronic-Mail in einem Führungskräfteteam - Eine qualitative und quantitative Untersuchung. PhD thesis, University of Dortmund.

HERRMANN Th (1995), Workflow Management Systems: Ensuring Organizational Flexibility by Possibilities of Adaptation and Negotiation. In ACM Conference on Organizational Computing Systems (COOCS) '95. Proceedings. New York: ACM Press.

HERRMANN Th, STAHL G (1998), Verschränkung der Perspektiven durch Aushandlung. In Sommer M, Remmele W, Klöckner K: Interaktion im Web, innovative Kommunikationsformen. Stuttgart: Teubner.

HERRMANN Th, STAHL G (1999), Intertwining Perspectives and Negotation. In Proceedings of the International ACM SIGGROUP Conference on Supporting Group Work. New York: ACM Press.

JANIS I L, MANN L (1977), Decision Making. A Psychological Analysis of Conflict, Choice, and Committment. New York: The Free Press.

KERRES M, ROSEMANN B (1992), Partizipationspotential und partizipatives Handeln bei Einführung neuer Technologien. Zeitschrift für Personalforschung, Vol. 6, No. 1. pp. 5-17.

KIRK J, COLEMAN J (1967), Formalisierung und Simulation von Interaktionen in einer Drei-Personen-Gruppe. In Mayntz R (Eds.), Formalisierte Modelle in der Soziologie. Neuwied et al.: Luchterhand.

LATANÉ B (1996), Dynamic Social Impact. In: Hegselmann R; Mueller U; Troitzsch KG (Eds.), Modelling and Simulation in the Social Sciences from the Philosophy of Science Point of View. Berlin: Springer, pp. 285-308.

LEPPERHOFF N (2001), Multi-agent systems and their reverse function: a first approach. In Urban Ch (Eds.), 2nd Workshop on Agent-Based Simulation. Ghent: SCS-Europe BVBA.

LEPPERHOFF N (2002), SAM - Untersuchung von Aushandlungen in Gruppen mittels Agentensimulation. Jülich: Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH.

LESSEL E (1985), Soziale Interdependenz. Computergestützte Theorieentwicklung für experimentelle Entscheidungssituationen. Frankfurt / Main: Peter Lang.

LINDSTÄEDT H (1998), Qualität von Gruppenentscheidungen. OR Spektrum, No. 20. pp. 165-177.

MANZ Th (1990), Akteurspezifische Voraussetzung in Betrieblichen Innovationsprozessen. In Kißler L (Eds.), Partizipation und Kompetenz. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.

MCGRATH J E (1984), Groups: Interaction and performance. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

MCGRATH J E (1993), Time, Interaction, and Performance (TIP) - A Theory of Groups. In Baecker R M (Eds.), Readings in Groupware and Computer-Supported Cooperative Work Assisting Human-Human Collaboration. San Francisco: Morgan Kauffmann.

NOWAK A; LEWENSTEIN M (1996), Modelling social change with cellular automata. In: Hegselmann R; Mueller U; Troitzsch KG (Eds.), Modelling and Simulation in the Social Sciences from the Philosophy of Science Point of View. Berlin: Springer, pp. 249-285.

ORTMANN R G (1995), Mikropolitische Prozesse in der Büroorganisation. In Eichener V, Mai M, Klein B (Eds.), Leitbilder der Büro- und Verwaltungsorganisation. Wiesbaden: Deutscher Universitätsverlag.

OSTMANN A (1992), On the relationship between formal conflict structure and the social field. Small Group Research, Vol. 23, No. 1. pp. 26-48.

PELZ J (1995), Gruppenarbeit via Computer: Sozialspychologische Aspekte eines Vergleichs zwischen direkter Kommunikation und Computerconferenz. Frankfurt /M. et al.: Peter Lang GmbH.

SADER M (1996), Psychologie der Gruppe. Weinheim: Juventa.

SCHNEIDER H-D (1985), Kleingruppenforschung. Stuttgart: Teubner.

SEBENIUS J K (1992), Negotiation Analysis: A Characterization and Review. Management Science, Vol. 38, No. 1, pp 18-38.

SIMMEL G (1958, first 1908), Soziologie: Untersuchungen über die Formen der Vergesellschaftung, 4th Edition. Berlin.

TROITZSCH K G (1996), Individuelle Einstellung und kollektives Verhalten. In Küppers G (Eds.), Chaos und Ordnung. Formen der Selbstorganisation in Natur und Gesellschaft. Stuttgart: Reclam.

TROITZSCH K G (1997), Social Sciences Simulation - Origins, Prospects, Purposes. In Conte R, Hegselmann R, Terna P (Eds.), Simulating Social Phenomena. Berlin et al.: Springer.

ZANDER A (1979), The Psychology of Group Process. Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 30. pp. 417-451.

Return to Contents of this issue

© Copyright Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, [2002]