Thursday, March 27. 2008

Peter Suber's Talk at Harvard's Berkman Center: "What Can Universities Do to Promote Open Access?"

Peter Suber gave an excellent talk at Harvard's Berkman Center for Internet and Society entitled: "What Can Universities Do to Promote Open Access?" and the discussion was very interesting too. The video and powerpoints are here.

SUMMARY: Eight supplemental points based on Peter Suber's excellent talk (and the audience discussion) on "What Can Universities Do To Promote Open Access?" at Harvard's Berkman Center for Internet and Society.

(1) Journals vs. books: OA is only about author give-away work. Peer-reviewed journal articles are all, without exception, author give-aways, but most scholarly books are not. OA can only be mandated for give-away work. (Once OA for journal articles prevails, more authors will undoubtedly want the same for their monographs too.)

(2) Versions and Citability: The canonical version of a journal article is the final, peer-reviewed, accepted version (the "postprint"). That is what researchers need, though not necessarily in the form of the publisher's PDF. What is cited is always the published work. Researchers are infinitely better off if those who cannot afford the publisher's official PDF can always access the author's self-archived postprint.

(3) First OA Self-Archiving Mandate: Queensland University of Technology's was the world's first university-wide OA self-archiving mandate, as Peter notes, but the very first OA self-archiving mandate of all was that of the School of Electronics and Computer Science at Southampton University.

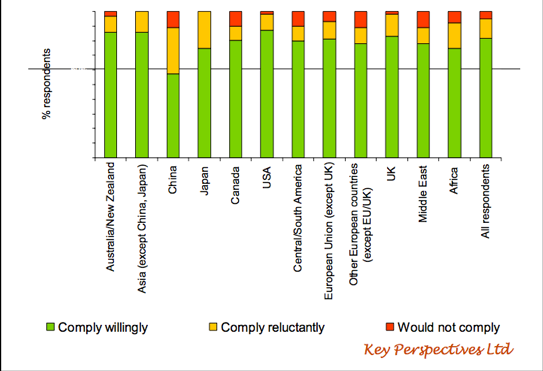

(4) Prior Evidence of Probability of Compliance With OA Self-Archiving Mandates: Swan & Brown's author surveys found that 95% of authors would comply with an OA self-archiving mandate (over 80% willingly) but authors were not asked whether they would comply with a copyright-retention mandate. The same is true of Arthur Sale's data on actual mandate compliance rates.

(5) Deposit Mandates vs. Copyright-Retention Mandates: NIH's is not a copyright-retention mandate. It is a no-opt-out deposit mandate plus a no-opt-out requirement to negotiate with the 38% of journals who don't endorse immediate OA, so as to be able to make the deposit OA within a year. Harvard's is a copyright-retention mandate, with opt-out.

(6) Mandate Implementation Mechanisms: There are no sanctions on deposit mandates, as Peter notes; there are administrative incentives and contingencies: The IR is made the official locus for submitting publications to be assessed for performance review.

(7) Peer Review, Journals and Repositories: Journals provide peer review; IRs provide access to peer-reviewed postprints. The issue of IRs providing peer review is a red herring (raised by others, not Peter).

(8) Journal Weighting in Researcher Performance Evaluation: [added 5 April] The credit and weight accorded for publishing in a given journal in a researcher's performance evaluation should depend only on the journal's track-record for quality, not on its OA policy or status.

I append eight comments stimulated by the talk and accompanying discussion; many are just elaborations on points Peter made:

(1) Journals vs. books: For the OA movement it is ever so important to clearly separate the case of journal articles from the case of books. The reason is simple: OA is and has to be only about author give-away work. Peer-reviewed journal articles are all, without exception, author give-aways, written only for uptake, usage and impact, not for royalty revenues.

Now although this may also be true of some scholarly books, it definitely is not true of all or most of them now. Hence not only can OA not be mandated for non-give-away books, but, at a time when OA itself is still so widely misunderstood, it is important to treat the clearcut, exception-free give-away case of peer-reviewed journal articles first, and separately, rather than to conflate it with the complicated hybrid case where the majority of the content is not author give-away at this time.

Once OA for journal articles prevails, more authors will undoubtedly want the same for their monographs too.

(2) Versions and Citability: The problems raised during the question period concerning the versions and citability problem are mostly a matter of misunderstanding:

First, we are talking about journal articles only.

The canonical version of a journal article is the final, peer-reviewed, accepted draft (the "postprint"). That is what researchers need, not necessarily the publisher's PDF.

What is cited is always the published work (unless one is explicitly and deliberately referring to unrefereed, unpublished prior drafts [preprints] or corrected, revised postpublication updates [which we could call "post-postprints"]). The version and citation issue pertains only to the specific case where one deliberately wishes to cite either an unpublished draft or an unpublished revision.

Otherwise, all citations of the peer-reviewed article itself -- whether based on reading the author's self-archived postprint of it, or the publisher's PDF of it -- are citations to the canonical published work itself (and point to the bibliographic data for the published work).

In other words: there is no special version or citation problem for postprints.

Now, as to the separate scholarly question of whether an author can be trusted if he says that "this draft of my published article is indeed the refereed final draft" -- that is a matter for scholarly practice and integrity. It is not an OA issue. It is not even a technical issue (although there are technical ways of computationally comparing versions to check whether and how a given draft diverges from the published PDF or XML text).

The only relevant point is that the scholarly and scientific research world is infinitely better off if all those scholars and scientists who cannot access the publisher's official PDF of any given article can always access the author's self-archived postprint of it. The possibility that some authors may sometimes be either untruthful or sloppy can be handled on a case by case basis if/when it ever comes up. But that possibility is definitely no reason to call into question the basic principle that what researchers need today is access to the postprint. And that it is in the authors' and their institutions' and their funders' best interests that authors should provide access to their postprints, by self-archiving them in their IRs. Inasmuch as self-archiving the publisher's PDF creates obstacles to self-archiving (because the publisher does not allow it, or because access to it is embargoed), that should definitely not be grounds for delaying the immediate provision of the author's postprint -- or for delaying the adoption of mandates to deposit it.

(3) First OA Self-Archiving Mandate: For the record: Queensland University of Technology's was indeed the world's first university-wide OA self-archiving mandate, as Peter noted, but not the world's first OA self-archiving mandate.

The very first OA self-archiving mandate was that of the School of Electronics and Computer Science at Southampton University in 2003: That was also the model for the first formal description of an OA self-archiving mandate in the BOAI Self-Archiving FAQ and the OSI EPrints Handbook.

(4) Prior Evidence of Probability of Compliance With OA Self-Archiving Mandates: It is not correct to say that the Swan & Brown author surveys found that authors would comply, and comply willingly, with any OA mandate at all. Authors were asked specifically about a mandate to deposit, and 95% said they would comply, with 81% complying willingly. They were not asked, however, about how they would feel about a mandate to retain copyright (let alone a mandate with an opt-out). Harvard's is the first copyright-retention mandate, and there is no evidence at all on how many faculty would comply, or comply willingly.

Arthur Sale's data on actual compliance rates likewise apply only to deposit mandates, not to copyright-retention mandates.

(5) Deposit Mandates vs. Copyright-Retention Mandates: NIH's is not a copyright-retention mandate. It is a deposit mandate. It can be fulfilled by simply depositing the postprint of an article that was published in any of the 62% Green journals that have endorsed immediate OA self-archiving, or any of the remaining journals that have endorsed embargoed access within NIH's time limit. That is a deposit mandate -- plus a requirement (with no opt-out option) to negotiate deposit within the embargo period for any remaining articles, published in journals that don't endorse immediate OA self-archiving. (Harvard's in contrast, is, in its present form, purely a copyright-retention mandate, with an opt-out.)

(6) Mandate Implementation Mechanisms: There are no sanctions on deposit mandates, but there are administrative incentives and contingencies, as Peter noted. Basically, if you wish to have your publications considered for institutional performance review, the official mechanism for doing so is to deposit them in your IR. (There is a similar rationale for fulfilling the Harvard copyright-retention mandate (for the non-opt-outs): one way to meet the condition of transmitting the postprint to the Provost is to deposit it directly in Harvard's IR.)

(7) Peer Review, Journals and Repositories: Very minor point: OA is about providing OA to peer-reviewed journal articles. OA journals can provide OA to their articles, or authors can provide OA to their articles (by depositing them in their IR). Singling out the fact that an IR does not provide peer review is a bit of a red herring. It risks encouraging people to speculate about alternatives to journals, instead of just focussing on providing OA to peer-reviewed journal articles. (Peter himself is of course very clear on this.)

(8) Journal Weighting in Researcher Performance Evaluation: In evaluating research performance, there need be no extra credit or weight accorded for publishing in a journal based on its OA policy or status. The weight should depend only, as always, on the journal's track-record for quality. OA can be provided by self-archiving articles published in any journal; there is no need for a researcher to select journals for any other reason than research quality.

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

The American Physical Society Is Not The Culprit: We Are (Part I)

[See also follow-up message: Part II.]

SUMMARY: A journal's copyright transfer agreement is too restrictive only if it tries to disallow author self-archiving of the accepted, refereed final draft (the "postprint"), free for all on the Web, where any user webwide can access, read, download, print-out, store, and data-mine that full-text for any research purpose whatsoever. The American Physical Society (APS) was always the most progressive of the established subscription-based publishers, and the very first to adopt a Green policy on author OA self-archiving. Today, 62% of journals are Green, but only about 15% of articles are being self-archived. Hence the first and foremost priority today is to get all authors self-archiving and all journals Green. Institutional and funder OA self-archiving mandates can and will ensure that both these things come to pass. This is not the time to be pursuing still more rights from Green publishers, particularly the most progressive one of all, APS. It's the time to self-archive and mandate self-archiving. The rest will take care of itself, but not if we keep chasing after what we don't need instead of grasping what is already within our reach.

"Physicists slam publishers over Wikipedia ban"I have some doubts about the accuracy of this New Scientist piece. What exactly is it that the American Physical Society (APS) is being alleged to be refusing to do?

New Scientist 16 March 2008

The APS is the first publisher that endorsed OA self-archiving. It is the greenest of green publishers. APS authors are encouraged to post their unrefereed preprints as well as their refereed postprints, free for all, on the web.

So what exactly is the fuss about?

"Scientists who want to describe their work on Wikipedia should not be forced to give up the kudos of a respected journal.""Describe" their work on Wikipedia? What does that mean? Of course they can describe their work (published or unpublished) on Wikipedia, or anywhere else.

And what has that to do with giving up the kudos of a respected journal?

Does this passage really mean to say "post the author's version to Wikipedia verbatim?" APS does not mind, but Wikipedia minds, because Wikipedia does not allow the posting of copyrighted work to Wikipedia.

Solution: Revise the text, so it's no longer the verbatim original but a new work the author has written, based on his original work. That can be posted to Wikipedia (but may soon be unrecognizably transformed -- for better or worse -- by legions of Wikimeddlers, some informed, some not). It's a good idea to cite the original canonical APS publication, though, just for the record.

Still nothing to do with APS.

"So says a group of physicists who are going head-to-head with a publisher because it will not allow them to post parts of their work to the online encyclopaedia, blogs and other forums."In a (free) online encyclopedia that would provide the author's original final draft, verbatim, and unalterable by users, there would be no problem (if the encyclopedia does not insist on copyright transfer) as long as there is a link to the original publication at the APS site.

Blogs and Forums (again on condition that the text itself cannot be bowdlerized by users, or re-sold) will be treated by APS as just another e-print server.

"The physicists were upset after the American Physical Society withdrew its offer to publish two studies in Physical Review Letters because the authors had asked for a rights agreement compatible with Wikipedia."This is now no longer about the right to post and re-post one's own published APS papers on the Web, it is about satisfying Wikipedia's copyright policy by going against APS's extremely liberal copyright policy. I side with APS. Let Wikipedia bend on this one, and let the text be posted (and then gang-rewritten as everyone sees fit). I see no reason why APS should have to alter its already sufficiently liberal policy to suit Wikipedia.

"The APS asks scientists to transfer their copyright to the society before they can publish in an APS journal. This prevents scientists contributing illustrations or other "derivative works" of their papers to many websites without explicit permission."APS already says authors can post their entire work just about anywhere on the web without explicit permission. And they can rewrite and republish their work too. This fuss is about formality, not substance.

"The authors of the rescinded papers and 38 other physicists are calling for the APS to change its policy. 'It is unreasonable and completely at odds with the practice in the field. Scientists want as broad an audience for their papers as possible,' says Bill Unruh at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, who has been lobbying separately against strict copyright rules."What possible online audience is broader than the entire Web, which is what you get when you make your article OA?

If we're going to lobby against strict copyright rules, let's pick any of the Gray, or even the Pale-Green publishers in Romeo. But lets leave the Green ones like APS alone until all publishers are at least as green as they are.

And if you are going to lobby against copyright rules, make sure it is about a matter of substance and not just form.

"'To tell us what we can do with our paper is completely at odds with practice in the field' Gene Sprouse, editor-in-chief of the APS journals, says the society plans to review its copyright policy at a meeting in May. 'A group of excellent scientists has asked us to consider revising our copyright, and we take them seriously,' he says."I am certain that the APS will accommodate all requests that are to the benefit of science, as they always have. I'm not always sure those who are lobbying for copyright reform really know what they want (or need) either. I trust them more if they say that they have made all their papers OA by self-archiving them. If they have not, yet they are still fussing, then they might be thinking of Disney re-mixes rather than science.

"Some publishers, such as the UK's Royal Society, have already adopted copyright policies that allow online reproduction."The APS has long had a far more liberal OA policy than the Royal Society, a reluctant late-comer to OA.

There is something being misreported or misunderstood here.

A journal's copyright transfer agreement is only too restrictive if it tries to disallow author self-archiving of the accepted, refereed final draft (the "postprint"), free for all on the Web, where any user webwide can access, read, download, print-out, store, and data-mine the full-text for any research purpose whatsoever. That is what is called "Open Access."

Journals that have a policy that formally endorses immediate and permanent author self-archiving of the postprint are called "Green" journals. There is a directory of the policies of the 10,000 principal journals regarding OA self-archiving: 62% of them are Green; 28% are "Pale-Green" (endorsing the self-archiving of pre-refereeing preprints, but not refereed postprints) and 9% are Gray (disallowing the self-archiving of either preprints or postprints).

The American Physical Society (APS) is fully Green; it is the first Green publisher and helped set the example for the rest of the Green publishers.

If anything needs changing today it's the policy of the 9% of journals that are Gray and the 28% that are Pale-Green, not the 62% that are Green.

Once all publishers are Green, and all authors are making their papers OA by self-archiving them, copyright agreements will come into phase with the new OA reality, and everything that comes with that territory. For that to happen, authors doing -- and publishers endorsing -- OA self-archiving is all that is necessary. There is no need to over-reach and insist on reforming copyright agreements.

NB: Whenever and wherever an author does succeed in retaining copyright, or a publisher does agree to just requesting a non-exclusive license rather than a total copyright transfer, that is always very welcome and valuable. But it is not necessary at this time, and over-reaching for it merely makes the task of securing the real necessity -- which is a Green self-archiving policy -- all the more difficult.

In particular, pillorying the APS, which was the earliest and most progressive of Green publishers, is not only unjust, but weakens the case against Gray publishers, who will triumphantly point out that they are justified in not going Green, because the demands of authors are excessive, unnecessary, and unreasonable, as they are not even satisfied with Green OA (and most don't even bother to self-archive)!

The problem for the worldwide research community is not the minority (about 15%, mostly concentrated in computer science and physics) who are already spontaneously making their articles OA by self-archiving them, but the vast majority (85%, across all disciplines, including even some areas of physics) who are not.

Moreover, there is something special about the longstanding practice in some parts of physics of posting and sharing unrefereed preprints: That practice is definitely not for all fields. Hence the universally generalizable component of the physicists' practice is the OA self-archiving of the refereed postprint. Posting one's unrefereed preprints will always be a contingent matter, depending on subject matter and author temperament. (Personally, I'm all for it for my own papers!)

There has been a big technical change since the first days of Arxiv. The online archives or repositories have been made interoperable by the OAI metadata harvesting protocol. Hence it is no longer necessary or even desirable to try to create an Arxiv-like central archive for each field, subfield, and interfield: Each researcher has an institution. Free software creates an OAI-compliant Institutional Repository (IR) where the authors in all fields at that institution can deposit all their papers. The OAI-compliant IRs are all interoperable (including Arxiv), and can then be searched and accessed through harvesters such as OAIster, Citebase, Citeseer or Google Scholar.

Institutional IRs also have the advantage that institutions (like Harvard) can mandate self-archiving for all their disciplines, thereby raising the 15% spontaneous (postprint) self-archiving rate to 100%. Research funders (like NIH) can reinforce institutional OA self-archiving mandates too.

The objective fact today is that all physicists, self-archiving or not, are still submitting their papers for refereeing and publication in peer-reviewed journals. Nothing whatsoever has changed in that regard. The only objective difference is that today (1) 15% of all authors self archive their postprints, and among some physics communities, (2) most are also self-archiving their preprints.

The OA movement is dedicated to generalizing the former practice (1) (self-archiving peer-reviewed postprints, so they can be accessed and used by all potential users, not just those whose institutions happen to be able to afford to subscribe to the journal in which they were published) to 100% of researchers, across all disciplines, worldwide.

Radical publishing reform -- like radical copyright reform -- are another matter, and may or may not eventually follow after we first have 100% OA. But for now, it is a matter of speculation, whereas postprint self-archiving is a reachable matter of urgency.

The physicists, from the very outset, had the good sense not to give it a second thought whether they were self-archiving with or without their journal's blessing. They just went ahead and did it!

But most researchers in other fields did not; and still don't, even today, when 62% of journals have given it their official blessing.

That's why self-archiving mandates are needed. (Author surveys have shown that over 90% of authors, in all fields, would comply, over 80% of them willingly -- but without a mandate they are simply too busy to bother -- just as in the case of the "publish or perish" mandate: if their promotion committees didn't require and reward publishing, many wouldn't bother to do that either!)

What is needed now is not to make a campaign of trying to force APS to change its copyright policy. What is needed now is to generalize APS's Green OA self-archiving policy to all publishers.

And to generalize the existing 39 university and funder Green OA (postprint) self-archiving mandates to all universities and funders.

The rest (copyright reform and publishing reform) will then take care of itself.

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Friday, March 21. 2008

One Small Step for NIH, One Giant Leap for Mankind

Peter Suber wrote in Open Access News:

Peter Suber wrote in Open Access News: PS: "It's one thing to argue that the NIH policy should mandate deposit in the author's institutional repository (when they have one)..."

Most universities have an Institutional Repository (IR).

Most universities have an Institutional Repository (IR).Even more would, if NIH mandated IR deposit as the preferred default option.

And those universities who don't yet have an IR are only a piece of free software and a few days' sysad start-up time from having one -- and not just for their NIH output, but for all their research output, funded and unfunded, in all disciplines.

The goal of the OA movement is to make all research output OA. But it is not just the OA content itself that needs to be "interoperable": OA mandates from funders need to be interoperable with OA mandates from institutions.

Institutions are -- without exception -- the source, the providers, of all research output, worldwide.

Hence funder OA mandates should not be competing with institutional OA mandates, needlessly and counterproductively, but adapting to, facilitating and reinforcing them.

It is not at all too late to correct this small -- but crucial and easily-fixed -- bug in the recent, welcome, timely flowering of funder OA mandates, to create a synergy with the potentially far bigger blooming of institutional OA mandates that is also on the horizon (as heralded by Harvard's recent OA mandate).

NIH need merely specify that the preferred means of fulfilling the NIH OA mandate is for NIH fundees to deposit their articles in their own institution's IR, and just send NIH each deposit's URL, so that PubMed Central can harvest it therefrom.

One small step for NIH, one giant leap for mankind.

PS: "But as long as the NIH is mandating deposit in PMC, and as long as a journal meets the NIH's criteria for depositing articles on behalf of authors, then I don't see any reason why authors shouldn't take advantage of the option."The reason is simple:

The NIH mandate, as it stands, does not scale up to providing a systematic means of covering all of institutional research output, NIH and non-NIH, funded and unfunded, across all disciplines worldwide.

NIH research output is just a small -- but extremely important -- subset of US and worldwide research output:

NIH, the world's biggest (nonmilitary) research funder, is providing a model for research funder mandates worldwide, a model that will be influential, closely watched, and widely emulated.

It is all the more critical, therefore, that the NIH mandate should be systematically scalable -- that it should interoperate coherently (rather than compete or conflict) with OA mandates from the research providers themselves -- the universities and research institutions worldwide -- as well as with other funder mandates, in other fields and other countries worldwide.

If, instead, authors and their institutions were now to begin ceding responsibility for compliance with the NIH OA mandate to their publishers as their proxies, relying on them to deposit their work in PubMed Central in their place, this would deprive the NIH mandate of any possibility of growing to cover all of research output, in all fields, worldwide. (It would also add to the compliance-monitoring and fulfillment problem that the Wellcome Trust, which has a similar funder mandate, is just now discovering -- and NIH will soon discover it too.)

Publisher proxy deposit would at the same time tighten the control of publishers over a process that should be entirely in the hands of authors themselves: the provision of supplementary free access to their give-away work for those who cannot afford paid access to the publisher's proprietary version. (Proxy deposit would also encourage publishers to charge for compliance with the NIH mandate.)

Publisher proxy deposit would also lose the three special, scalable strengths of the NIH mandate, which are (1) that the NIH mandate applies specifically to the researcher's peer-reviewed final draft (the postprint, on which restrictions are the fewest), not necessarily to the publisher's proprietary PDF; (2) that the NIH mandate is a researcher self-archiving mandate, binding on researchers (not their publishers), and based on each researcher's right (and responsibility) to maximize access to his own give-away findings; and (3) that the NIH mandate is a coherent component of a universal mandate to provide OA to all research output, not just to NIH-funded research output, in PubMed Central.

It is crucially important to remind ourselves very explicitly that what we are talking about here is just keystrokes -- i.e., about who should do the few keystrokes that make a piece of peer-reviewed research OA. We are talking, very specifically, about a few minutes' worth of keystrokes per paper (over and above the many keystrokes that already went into writing it in the first place). The natural ones to do those keystrokes are the authors themselves (or their assistants, students or assigns); and the natural place for them to do it is in their own IRs. It makes as little sense to consider offloading the task of performing those few keystrokes onto publishers (or even onto institutional librarians) as it would be to offload onto any other party the task of keying in the paper itself, in these days of personal word-processing.

So although most authors today are still not doing those few extra keystrokes of their own accord (and that is precisely the problem that the OA mandates are meant to remedy) it would be exceedingly short-sighted to propose that the remedy is to invite authors' publishers to do those keystrokes for them (possibly even at additional cost). That dysfunctional remedy is remarkably reminiscent of the grotesque degree of control over the dissemination of our own giveaway research findings we have unwittingly been ceding to our publishers throughout the paper era (the "Faustian Bargain"): the very disease that OA is meant to cure, in the online era, at long last.

And needlessly insisting on direct deposit in PubMed Central is the very heart of the problem. Yet the cure is ever so simple: NIH need merely stipulate that the preferred means of fulfilling the NIH OA mandate is for each researcher to deposit the postprint in his own university's IR and send NIH the URL.

PS: "I did object to journal deposit under the older, voluntary policy, because it gave publishers the decision on the length of the embargo. Under the new policy, however, the length of the embargo is already set by the time the author signs the copyright transfer agreement. Hence, journal deposit cannot change the terms of the deal."That leaves only the six other serious reasons militating against publisher deposit: (1) Publisher proxy deposit in an external repository needlessly competes with institutional IR self-archiving mandates instead of facilitating them; (2) it defeats the benefits of an immediate-deposit mandate, where the IR's "email eprint request" button could have tided over worldwide research usage needs during any publisher embargo by providing almost-immediate, almost-OA; (3) it loses the benefits of having specified that the OA deposit target is the author's postprint, not necessarily the publisher's PDF; (4) it leaves publishers in control of providing OA (and even facilitates their charging for it); (5) it leaves IRs empty, and non-NIH content non-OA; (6) it leaves researchers' fingers paralyzed.

PS: [update] "My response above was limited to publishers who do not charge fees, and I share Stevan's objections to those who would charge fees."My objections are not just limited to publishers who charge fees: They concern any publisher proxy deposit, and indeed any funder mandate that does not stipulate that the author's own institutional IR is the preferred default locus for deposit wherever possible.

PS: "Or if there's some subtle way in which it can, then I'll join Stevan's call on authors to make the deposits themselves. I already agree with him that, if the policy were to mandate deposit in the author's IR, then author deposits would make much more sense than journal deposits."Peter, the ways in which both publisher proxy deposit and direct institution-external deposit are counterproductive for the growth of OA and OA mandates are far from subtle. I fervently hope that you will support my call on authors (or their collaborators) to make the deposits themselves, preferably in their own IRs, providing NIH with the URL. And of course also the call on NIH to allow -- indeed welcome -- IR deposit and PubMed Central harvesting rather than just direct PubMed Central deposit. (And, while we're at it, the call on universities, like Harvard, to mandate deposit, without opt-out, rather than just mandating copyright-retention, with opt-out!)

This slight change in the implementational details of the NIH policy would be a small step for NIH, but a huge step for the growth of OA worldwide.

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Publisher Proxy Deposit Is A Potential Trojan Horse: III

Paul Gherman: "At Vanderbilt, our Medical Library has been doing significant work contacting publishers to find out what their policy and procedures are. One discovery is that some of them intend to charge authors between $900 and $3,000 to submit articles to NIH. Some will allow for early posting, if the fee is paid."Such are the wages of whim.

But they are easily fixed, free of charge:

(1) NIH specifies the researcher's own Institutional Repository (IR) as the locus for the mandated direct deposit. (PubMed Central can then harvest the metadata or full-text.)The (outrageous) notion of being charged $900 - $3000 per paper for complying with the NIH Green OA self-archiving mandate is something the NIH has invited upon itself by not thinking through the details of the mandate sufficiently, and mandating direct 3rd-party repository deposit instead of integrating the NIH mandate with Harvard-style university mandates, requiring immediate deposit in the university employee's own IR, without exceptions or opt-outs, and with embargoed OA access-setting the only (temporary) compromise.

(2) Universities mandate deposit in their IRs immediately upon acceptance for publication (for all their research output, not just NIH).

(3) The deposit must be immediate; the access too should be set as OA immediately, but it may optionally be set as Closed Access during a limited embargo period (during which all research user needs can be fulfilled with the help of the IR's semi-automatic "email eprint request" button).

(4) Along with encouraging (but not mandating) setting access to the (mandated) immediate deposit as Open Access rather than Closed Access wherever possible, universities can also encourage (but not mandate -- because a mandate with an opt-out option is not a mandate anyway) Harvard-style copyright retention wherever possible.

I am confident that this will be the ultimate outcome in any case. The only question is: How long will it take all the wise and well-intentioned parties involved to take a deep breath, think it through, and do it, instead of hurtling ahead with alternatives they have already committed themselves to, without thinking them through sufficiently rigorously...?

See: "How To Integrate University and Funder Open Access Mandates"Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Publisher Proxy Deposit Is A Potential Trojan Horse: II

AO: "Right now we have a kind of mess that needs time to sort out: trying to achieve compliance for literally thousands of authors and articles in a couple of months (since the mandate was announced in January) is a herculean task, when the institutional underpinnings (the list of these is substantial) are mostly not yet present. We have a situation in which articles can be submitted by (1) authors, many of whom would rather just have someone else do it, like the publishers -- btw, the NIH instructions for authors are not as helpful as they could be; (2) the research institutions, i.e., the ones that already have everything in place to do so; or (3) the publishers. The potential for redundancy is huge and it is wasteful. The publishers, most of whom are willing to help if given half a chance, are the ones with the redacted articles... seem like the most logical funnel to the NIH, if this can be worked out.The institutions who "already have everything in place to do so" can sort this out in one simple, sensible swoop:

"Wouldn't it be good if the NIH, the publishers, and the research institutions would get into a room together and thrash this all out in an sensible way?"

Institutions mandate deposit in their own Institutional Repositories and invite NIH to harvest from there (or hack up an export of NIH content to PubMed Central).

The institutions whose "institutional underpinnings [they are not substantial] are... not yet present" are only a piece of free software plus a few days of sysad time away from having the requisite institutional underpinnings present.

A hasty stopgap strategy of relying on proxy deposit by publishers would be the very worst possible solution. It not only doesn't scale, but it positively obstructs the goal of systematically making all institutional research output OA (playing into the hands of those like-minded publishers who have that very goal).

We must think beyond just the NIH OA mandate to mandating OA for all all university research output, funded and unfunded, in all disciplines.

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Wednesday, March 19. 2008

Open Access Now: On the Virtues of Not Over-Reaching, Needlessly

"If peer-reviewed papers are allowed to be posted on IRs and personal web sites, how is this not open access? My understanding is that this is what Stevan Harnad calls Green OA."Yes indeed, peer-reviewed papers, being deposited and made freely accessible in an IR, is indeed Open Access (OA) -- 100% full-blooded OA (and there's only one OA: Green OA self-archiving and Gold OA publishing are just two different ways to provide OA).

I think I can sort out the confusion (and disagreement):

The original BOAI definition went a little overboard in "defining" OA.

(I am co-culpable, since I was one of the co-drafters and co-signers, but I confess I was inattentive to these details at the time. If I had been thinking more carefully, I could have anticipated the consequences and dissented from the definition before it was co-signed. As it happened, I dissented later.)

The original definition of OA did not just require that the full-text be accessible free for all on the web; it also required author-licensed user re-use and re-publication rights (presumably both online and on-paper).

If I had not been too addle-brained to realize it at the time, it would have been obvious that this could not possibly be the definition of OA, if we were not going to price ourselves right off the market: We had (rightly) claimed that what had made OA possible was the new medium (the Net and the Web), which had for the first time made it possible for the authors of peer-reviewed journal articles (all of them, always, author give-aways, written only for usage and impact, not access-toll income) to give away their give-away work big-time, at last, as they had always wanted to do (and had already been doing for decades, in a much more limited way, in mailing reprints to requesters).

That fundamental new fact would have been turned into just an empty epiphenomenal totem if our punch-line had been that on-paper [i.e., print] re-publication rights are part of OA! For one could just as well have claimed that in the paper era (and no one would have listened, rightly).

Third-party paper re-publication rights have absolutely nothing to do with OA -- directly. OA is an online matter.

Of course, once Green OA prevails, and all peer-reviewed papers are accessible for free, worldwide, 24/7, online, then on-paper re-publication rights will simply become moot, because there will be no use for them!

And that's why I was so obtuse about the original BOAI definition of OA: Because although it was premature to talk about paper re-publication rights, those would obviously come with the OA territory, eventually; so (I must have mused, foolishly) we might as well make them part of our definition of OA from the outset.

Well, no, that was a mistake, and is now one of the (many) reasons the onset of the "outset" is taking so long to set in! Because here we are, over-reaching, needlessly, for rights we don't need (and that will in any case eventually come with the OA territory of their own accord) at the cost of continuing to delay OA by demanding more than we need.

The same is true about the other aspects of this unnecessary and counterproductive over-reaching: Just about all of what some of us are insisting on demanding formally and legalistically already comes with the free online (i.e., OA) territory (and immediately, today, not later, as re-publishing rights will, after OA prevails):

We don't need to license the right to download, store, print-off and (locally) data-mine OA content. That's already part of what it means for a text to be freely accessible online.

Nor do we need to insist on the right to re-publish the text in course-packs for teaching purposes: Distributing just the URL has exactly the same effect!

Re-publishing by a third party (neither the publisher, nor the author, nor the author's employer) is another matter, however, whether online or on paper.

Simple online re-publishing is vacuous, because, again, harvesting the URLs and linking to the OA version in the IR is virtually the same thing (and will hence dissolve this barrier completely soon enough, with no need of advance formalities or legalities).

Third-party re-publishing on-paper (print) will have to wait its turn; it is definitely not part of OA itself -- but, as noted, to the extent that there is any use left for it at all, it will eventually follow too, once all peer-reviewed research is OA, for purely functional reasons.

Finally, Google can and will immediately machine-harvest and data-mine OA content, just as it harvests all other freely accessible online content. It will also reverse-index it and "re-publish" it in bits, online. Other data-mined database providers may not get away with that initially -- but again, once we reach 100% OA this barrier too will dissolve soon thereafter, for purely functional reasons. It is not, however, part of OA itself; and insisting on it now, pre-emptively (and unnecessarily) will simply delay OA, by demanding more than we need -- because more is always harder to get than less.

And (to finish this rant) this is why I have urgently urged a small but critical change in the Harvard-style copyright-retention mandates (which, because they ask for more than necessary, need to add an opt-out clause, which means they end up getting less than necessary): We don't need to mandate copyright retention at this time. It's wonderful and highly desirable to have it if/when you can have it, but it is not necessary for OA. And OA itself will soon bring on all the rest.

All that's necessary for OA is free online access. Indeed -- and I'm afraid I risk getting Sandy's hackles up with this one again, so I will avoid using the controversial phrase "Fair Use" -- mandating immediate full-text deposit, without opt-out, with the option of making access to the full text OA wherever already endorsed by the journal (62%) and "almost OA" (i.e., Closed Access plus the semi-automatic "email eprint request") for the rest will be sufficient to get us to 100% OA not too long thereafter.

Holding out instead for copyright-retention, with an author opt-out option, in order to try to ensure getting 100% OA from the outset, is simply a way to ensure getting nowhere near 100% OA-plus-almost-OA from the outset, because of author opt-outs.

Summary: OA is free online access, and the necessary and sufficient condition for reliably reaching 100% OA soon after the mandate is implemented is to mandate immediate deposit with no opt-out. There is no need for licensed re-use and re-publication rights; copyright retention should just be described as a highly recommended option (which is what a "mandate with an opt-out" amounts to anyway). All the rest will happen of its own accord after 100% immediate-deposit is achieved. (The only obstacle to 100% OA all along has been keystrokes, nothing but keystrokes, for which all that is needed is a keystroke mandate.)

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Tuesday, March 18. 2008

Publisher Proxy Deposit Is A Potential Trojan Horse: I

I suggest not colluding with publishers offering to "Let us do the [mandated] deposit for you".Ann Okerson: "If your publishing organization is providing for your authors the service of deposit of their articles according to various mandates, particularly NIH (beginning on 4/7) could you kindly describe the nature or extent of these services"Paul Gherman: "At Vanderbilt, our Medical Library has been doing significant work contacting publishers to find out what their policy and procedures are. One discovery is that some of them intend to charge authors between $900 and $3,000 to submit articles to NIH. Some will allow for early posting, if the fee is paid."

The reason is simple, if we take the moment to think it through:

(1) The OA movement's goal is to provide Open Access (OA) to 100% of the world's peer-reviewed research article output.[Similar considerations, but on a much lesser scale, militate against the strategy of universities out-sourcing the creation and management of their IRs and self-archiving policies to external contractors: accounting, archiving, record-keeping and asset management should surely be kept under direct local control by universities. There's nothing so complicated or daunting about self-archiving and IRs as to require resorting to an external service. (More tentatively, I am also sceptical that library proxy self-archiving rather than direct author self-archiving is a wise choice in the long run -- though it is definitely a useful option as a start-up supplement, if coupled with a mandate, and has been successfully implemented in several cases, including QUT and CERN.)]

(2) The goal of [some] publishers is to preserve the status quo -- or the closest approximation to it -- for as long as possible, at all costs.

(3) The providers of both the research and the peer review, in all disciplines, are the employees of the universities (and research institutions) worldwide (and the fundees of the funded research).

(4) The only way to cover all of OA's target space is for all research output, from all universities worldwide, funded and unfunded, across all disciplines, to be made OA.

(5) OA self-archiving mandates from universities and funders (39 so far, worldwide) can ensure that all research is made OA.

(6) Some funders (e.g. NIH) -- but no universities (e.g. Harvard) -- have mandated direct university-external self-archiving (in PubMed Central) instead of direct university-internal self-archiving (and subsequent central harvesting). This was an unnecessary strategic mistake.

(7) University-external, subject-based self-archiving does not scale up to cover all of OA output space: it is divergent, divisive, arbitrary, incoherent and unnecessary.

(8) The way to scale up systematically to capture all of OA output is for both funders and universities to mandate that all research output, in all disciplines, from all universities worldwide, funded and unfunded, should be self-archived in each university's own Institutional Repository (IR). (The deposits, or their metadata, can then be externally harvested into whatever subject-based, disciplinary, or multidisciplinary central collections we may desire.)

(9) The universities are the research providers; the universities are the co-beneficiaries of showcasing, archiving, auditing, assessing and maximizing the visibility, usage and impact of (all) their own research output, funded and unfunded, across all disciplines.

(10) The universities are also in the natural and optimal position to monitor and reward their own employees' compliance with both university and funder self-archiving mandates.

(11) It would hence systematically undermine the scaling and convergence of OA self-archiving mandates onto university IRs to transfer responsibility for compliance to an external party -- the publisher as their employees' proxy self-archiver -- depositing in arbitrary and divergent external repositories.

(12) Universities and funders should universally mandate self-archiving directly in each author's own university's IR; they should say "no, thank you" to offers of proxy self-archiving on behalf of their employees from publishers. External collections can then be harvested, as desired, from the IRs that will then cover 100% of OA output.

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Wednesday, March 12. 2008

The Special Case of Law Reviews

Law Library Director and Assistant Professor of Law at the University of New Mexico School of Law, Carol Parker, has published an article in the New Mexico Law Review, Vol. 37, No. 2, Summer 2007 (just blogged by Peter Suber in Open Access News), entitled "Institutional Repositories and the Principle of Open Access: Changing the Way We Think About Legal Scholarship."

Law Library Director and Assistant Professor of Law at the University of New Mexico School of Law, Carol Parker, has published an article in the New Mexico Law Review, Vol. 37, No. 2, Summer 2007 (just blogged by Peter Suber in Open Access News), entitled "Institutional Repositories and the Principle of Open Access: Changing the Way We Think About Legal Scholarship."Though a bit out of date now in some of its statistics, because things are moving so fast, this article gives a very good overview of OA and concludes that, no, Law Reviews are not a special case: Those articles, too, and their authors and institutions, would benefit from being self-archived in each author's Institutional Repository to make them OA.

Professor Parker conjectures that most potential users worldwide already have affordable subscription access to all the law journal articles they need via Westlaw and Lexis, so the advantage of OA in Law might be just one of speed and convenience, not a remedy for access-denial.

(This might be the case, but I wonder if anyone actually has quantitative evidence, canvassing users across institutions worldwide for research accessibility, and comparing Law with other disciplines?)

In any case, if you haven't already seen it, Professor Parker's article is highly recommended and in light of the recent NIH, ERC, and Harvard self-archiving mandates and ongoing deliberations about further mandates worldwide, the article is especially timely.

Prior Topic Thread on American Scientist Open Access Forum:Stevan Harnad

"The Special Case of Law Reviews" (thread began 2003)

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Sunday, March 9. 2008

Open Access Koans, Mantras and Mandates

On Sun, 9 Mar 2008, Andy Powell [AP] wrote in JISC-REPOSITORIES:

On Sun, 9 Mar 2008, Andy Powell [AP] wrote in JISC-REPOSITORIES: AP: You can repeat the IR mantra as many times as you like... it doesn't make it true.Plenty of figures have been posted on how much money institutions have wasted on their (empty) IRs in the eight years since IRs began. People needlessly waste a lot of money on lots of needless things. The amount wasted is of no intrinsic interest in and of itself.

Despite who-knows-how-much-funding being pumped into IRs globally (can anyone begin to put a figure on this, even in the UK?)...

The relevant figure is this:

For the answer, you do not have to go far: Just ask the dozen universities that have so far done both: The very first IR-plus-mandate was a departmental one (at Southampton ECS); but the most relevant figures will come from university-wide mandated IRs, and for those figures you should ask Tom Cochrane at QUT and Eloy Rodrigues at Minho (distinguishing the one-time start-up cost from the annual maintenance cost).How much does it actually cost just to set up an OA IR and to implement a self-archiving mandate to fill it?

And then compare the cost of that (relative to each university's annual research output) with what it would have cost (someone: whom?) to set up subject-based CRs (which? where? how many?) for all of that same university annual research output, in every subject, willy-nilly worldwide, and to ensure (how?) that it was all deposited in its respective CR.

(Please do not reply with social-theoretic mantras but with precisely what data you propose to base your comparative estimate upon!)

AP: most [IRs] remain largely unfilled and our only response is to say that funding bodies and institutions need to force researchers to deposit when they clearly don't want to of their own free will. We haven't (yet) succeeded in building services that researchers find compelling to use.We haven't (yet) succeeded in persuading researchers to publish of their own free will: So instead of waiting for researchers to wait to find compelling reasons to publish of their own free will, we audit and reward their research performance according to whether and what they publish ("publish or perish").

We also haven't (yet) succeeded in persuading researchers to publish research that is important and useful to research progress: So instead of waiting for researchers to wait to find compelling reasons to maximise their research impact, we review and reward research performance on the basis not just of how much research they publish, but also its research impact metrics.

Mandating that researchers maximise the potential usage and impact of their research by self-archiving it in their own IR, and auditing and rewarding that they do so, seems a quite natural (though long overdue) extension of what universities are all doing already.

AP: If we want to build compelling scholarly social networks (which is essentially what any 'repository' system should be) then we might be better to start by thinking in terms of the social networks that currently exist in the research community - social networks that are largely independent of the institution.Some of us have been thinking about building on these "social networks" since the early 1990's and we have noted that -- apart from the very few communities where these self-archiver networks formed spontaneously early on -- most disciplines have not followed the examples of those few communities in the ensuing decade and a half, even after repeatedly hearing the mantra (Mantra 1) urging them to do so, along with the growing empirical evidence of self-archiving's beneficial effects on research usage and impact (Mantra 2).

Then the evidence from the homologous precedent and example of (a) the institutional incentive system underlying publish-or-perish as well as (b) research metric assessment was reinforced by Alma Swan's JISC surveys: These found that (c) the vast majority of researchers report that they would not self-archive spontaneously of their own accord if their institutions and/or funders did not require it (mainly because they were busy with their institutions' and funders' other priorities), but 95% of them would self-archive their research if their institutions and/or funders were to require it -- and over 80% of them would do so willingly (Mantra 3).

Then the evidence from the homologous precedent and example of (a) the institutional incentive system underlying publish-or-perish as well as (b) research metric assessment was reinforced by Alma Swan's JISC surveys: These found that (c) the vast majority of researchers report that they would not self-archive spontaneously of their own accord if their institutions and/or funders did not require it (mainly because they were busy with their institutions' and funders' other priorities), but 95% of them would self-archive their research if their institutions and/or funders were to require it -- and over 80% of them would do so willingly (Mantra 3).

And then Arthur Sale's empirical comparisons of what researchers actually do when such requirements are and are not implemented fully confirmed what the surveys said that the researchers (across all disciplines and "social networks" worldwide) had said they would and would not do, and under what conditions (Mantra 4).

So I'd say we should not waste another decade and a half waiting for those fabled "social networks" to form spontaneously so the research community can at last have the OA that has not only already been demonstrated to be feasible and beneficial to them, but that they themselves have signed countless petitions to demand.

Indeed it is more a koan than a mantra that the only thing the researchers are not doing for the OA they overwhelmingly purport to desire is the few keystrokes per paper that it would it take to do a deposit rather than just sign a petition! (And it is in order to generate those keystrokes that the mandates are needed.)

AP: Oddly, to do that we might do well to change our thinking about how best to surface scholarly content on the Web to be both 1) user-centric (acknowledging that individual researchers want to take responsibility for how they surface their content, as happens, say, in the blogsphere) and 2) globally-centric (acknowledging that the infrastructure is now available that allows us to realise the efficiency savings and social network effects of large-scale globally concentrated services, as happens in, say, Slideshare, Flickr and so on).It is odd indeed that all these wonders of technology, so readily taken up spontaneously when people are playing computer games or blabbing in the blogosphere have not yet been systematically applied to their ergonomic practices, but the fact is that (aside from a few longstanding social networks) they have not been, and we have waited more than long enough. That systematic application is precisely what the now-growing wave of OA self-archiving mandates by funders (such as RCUK and NIH) and universities (such as Southampton ECS and Harvard) is meant to accelerate and ensure.

AP: Such a change in thinking does not rule the institution out of the picture, since the institution remains a significant stakeholder with significant interests... but it certainly does change the emphasis and direction and it hopefully stops us putting institutional needs higher up the agenda than the needs of the individual researcher.Individual researchers do not work in a vacuum. That is why we have institutions and funders. Those "research networks" already exist. As much as we may all admire the spontaneous, anonymous way in which (for example) Wikipedia is growing, we also have to note the repeatedly voiced laments of those academics who devote large portions of their time to such web-based activities without being rewarded for it by their institutions and funders (Mantra 5).

OA self-archiving mandates are precisely the bridge between (i) the existing canonical "social networks" and reward systems of the scholarly and scientific community -- their universities and research funders -- and (ii) the new world that is open before them.

OA self-archiving mandates are precisely the bridge between (i) the existing canonical "social networks" and reward systems of the scholarly and scientific community -- their universities and research funders -- and (ii) the new world that is open before them.It is time we crossed that bridge, at long last (Mantra 6).

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Tuesday, March 4. 2008

Surf Foundation Publisher Policy Survey

The Surf Foundation has released a survey on "Acceptance of the JISC/SURF Licence to Publish & accompanying Principles by traditional publishers of journals."

The Surf Foundation has released a survey on "Acceptance of the JISC/SURF Licence to Publish & accompanying Principles by traditional publishers of journals."The gist of the survey result is that more and more publishers are moving toward explicitly endorsing author open-access self-archiving, and that the majority already endorse it.

This is good to know, but it was already evident from the EPrint Romeo statistics (derived by clarifying the SHERPA-Romeo data, and presenting it at the individual journal level). These statistics have been available and regularly updated for several years now.

Two comments:

(1) The Surf Foundation survey obscures the results somewhat, because it uses the needlessly profligate, irrelevant and confusing colour codes of SHERPA-Romeo ("green", "blue", "yellow", "white") when all we need to know is:Stevan HarnadGREEN (62%) (journals that endorse immediate open-access self-archiving of the peer-reviewed postprint)(2) There is some confusion about what is meant by "open access" in the Surf report (whether (i) Gold Open Access journal publishing, (ii) Green Open Access author self-archiving, or (iii) the adoption of the JISC/SURF licensing recommendations).

PALE-GREEN (29%) (journals that endorse only unrefereed preprint self-archiving)

OTHER (9%) (journals that do not endorse self-archiving of either preprint or postprint, that embargo self-archiving, or that charge authors money to self-archive)

For articles in the GREEN journals (62%) that endorse immediate author self-archiving of the postprint there is no need for the JISC/SURF license. It is always welcome, but not necessary in order to provide Open Access. (And even for articles the 38% non-GREEN journals, repositories can implement the "email eprint request" button to facilitate users requesting and authors providing almost-immediate, almost-OA while trying to renegotiate copyright, waiting for the embargo to elapse, or waiting for the journal to go GREEN.)

American Scientist Open Access Forum

(Page 1 of 2, totaling 12 entries)

» next page

EnablingOpenScholarship (EOS)

Quicksearch

Syndicate This Blog

Materials You Are Invited To Use To Promote OA Self-Archiving:

Videos:

audio WOS

Wizards of OA -

audio U Indiana

Scientometrics -

The American Scientist Open Access Forum has been chronicling and often directing the course of progress in providing Open Access to Universities' Peer-Reviewed Research Articles since its inception in the US in 1998 by the American Scientist, published by the Sigma Xi Society.

The American Scientist Open Access Forum has been chronicling and often directing the course of progress in providing Open Access to Universities' Peer-Reviewed Research Articles since its inception in the US in 1998 by the American Scientist, published by the Sigma Xi Society.

The Forum is largely for policy-makers at universities, research institutions and research funding agencies worldwide who are interested in institutional Open Acess Provision policy. (It is not a general discussion group for serials, pricing or publishing issues: it is specifically focussed on institutional Open Acess policy.)

You can sign on to the Forum here.

Archives

Calendar

Categories

Blog Administration

Statistics

Last entry: 2018-09-14 13:27

1129 entries written

238 comments have been made