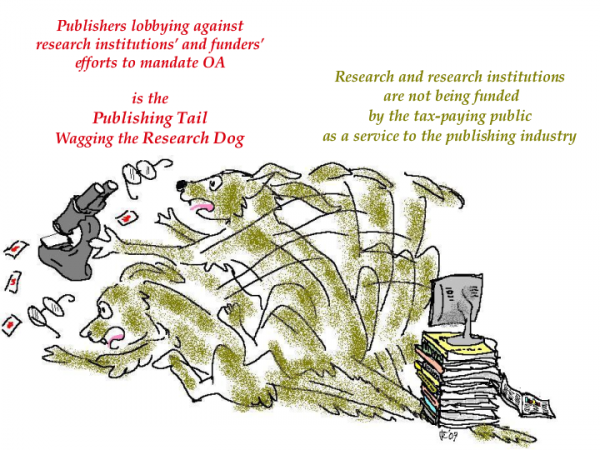

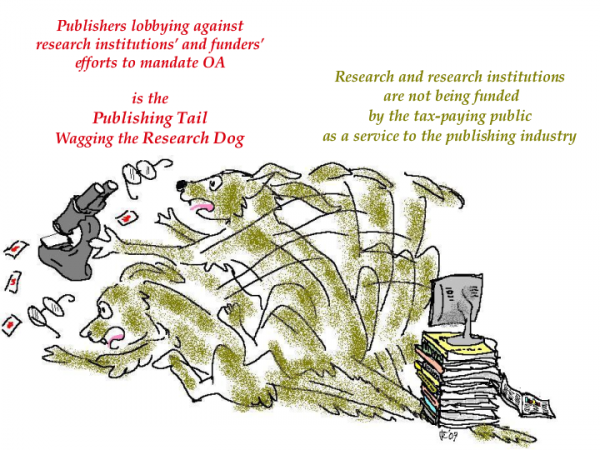

(Actually, publishing is not even the tail of research but the flea on the tail...)

(Actually, publishing is not even the tail of research but the flea on the tail...)

The US Research Works Act (H.R.3699)

The US Research Works Act (H.R.3699):

"No Federal agency may adopt, implement, maintain, continue, or otherwise engage in any policy, program, or other activity that -- (1) causes, permits, or authorizes network dissemination of any private-sector research work without the prior consent of the publisher of such work; or (2) requires that any actual or prospective author, or the employer of such an actual or prospective author, assent to network dissemination of a private-sector research work."Translation and Comments:

"If public tax money is used to fund research, that research becomes "private research" once a publisher "adds value" to it by managing the peer review." [Comment: Researchers do the peer review for the publisher for free, just as researchers give their papers to the publisher for free, together with the exclusive right to sell subscriptions to it, on-paper and online, seeking and receiving no fee or royalty in return].

"Since that public research has thereby been transformed into "private research," and the publisher's property, the government that funded it with public tax money should not be allowed to require the funded author to make it accessible for free online for those users who cannot afford subscription access."

[Comment: The author's sole purpose in doing and publishing the research, without seeking any fee or royalties, is so that all potential users can access, use and build upon it, in further research and applications, to the benefit of the public that funded it; this is also the sole purpose for which public tax money is used to fund research.]"

H.R. 3699 misunderstands the secondary, service role that peer-reviewed research journal publishing plays in US research and development and its (public) funding.

It is a huge miscalculation to weigh the potential gains or losses from providing or not providing open access to publicly funded research in terms of gains or losses to the

publishing industry: Lost or delayed research progress mean losses to the growth and productivity of both

basic research and the vast

R&D industry in all fields, and hence losses to the

US economy as a whole.

What needs to be done about

public access to peer-reviewed scholarly publications resulting from federally funded research?

The minimum policy is for all US federal funders to mandate (require), as a condition for receiving public funding for research, that: (i) the fundee’s revised, accepted refereed final draft of (ii) all refereed journal articles resulting from the funded research must be (iii) deposited immediately upon acceptance for publication (iv) in the fundee'’s institutional repository, with (v) access to the deposit made free for all (OA) immediately (no OA embargo) wherever possible (over 60% of journals already endorse immediate gratis OA self-archiving), and at the latest after a 6-month embargo on OA.

It is the above policy that H.R.3699 is attempting to make illegal.

The purpose of mandating open access to federally funded research findings is to ensure that the findings are accessible to all their potential users, not just (as in the print era) to those whose institutions can afford subscription access to the journal in which they happened to be published.

Unlike trade magazine and newspaper articles, whose authors write them for fees or royalties, research journal articles are author give-aways, written solely for research uptake and impact. Hence unlike trade publishing, peer-reviewed research journal publishing is a

service industry. It exists in the service of research, researchers and research progress. These are vastly larger and more crucial economically than research journal publishing itself, as a business. Hence it is the research publishing industry that must adapt to the powerful new potential that the online era has opened up for research, researchers, research institutions, research funders, the vast R&D industry, teachers, students, and the tax-paying public that funds the research. Not vice versa.

A vast new potential for research has been opened up by the Web. It would be a great mistake, economically speaking, if research, researchers, the R&D industry and the US tax-paying public all had to renounce this newfound potential so as to protect and preserve the current revenue streams and M.O. of the publishing industry. That M.O. evolved for the technology and economics of the bygone Gutenberg era of print on paper. H.R.3699 would prevent evolution from continuing, to allow research to reap the full benefit of the PostGutenberg era.

Requiring research to adapt to publishing would amount to the publishing tail wagging the research dog: The peer-reviewed research publishing industry exists as a service industry for research, not vice versa:

Publicly funded research is entitled to the full scientific and public benefits opened up for it by the online era.

Foremost among these benefits is the fact that (online) access to publicly funded research need no longer be restricted to those users who subscribe to the journal in which it was published. The research publishing industry can and will continue to evolve until it adapts naturally to the age of free online access to research.

Among the many important implications of

Houghton et al’s (2009) timely and illuminating analysis of the costs and benefits of providing free online access (OA) to peer-reviewed scholarly and scientific journal articles one stands out as particularly compelling: It would yield a forty-fold benefit/cost ratio if the world’s peer-reviewed research were all self-archived by its authors so as to make it OA. There are many assumptions and estimates underlying Houghton et al’s modelling and analyses, but they are for the most part very reasonable and even conservative. This makes their strongest practical implication particularly striking: The 40-fold benefit/cost ratio of providing Green OA is an order of magnitude greater than all the other potential combinations of alternatives to the status quo analyzed and compared by Houghton et al. This outcome is all the more significant in light of the fact that self-archiving already rests entirely in the hands of the research community (researchers, their institutions and their funders), whereas OA publishing depends on the publishing community. Perhaps most remarkable is the fact that this outcome emerged from studies that approached the problem primarily from the standpoint of the economics of publication rather than the economics of research.

It is hence ironic that some publishers are calling Open Access self-archiving by authors ("Green OA") “parasitic” on their "added value," when not only are researchers giving publishers their articles for free, as well as peer-reviewing them for free, but research institutions are paying for subscriptions in full, covering all publishing costs and profits. The only natural and obvious source of funds to pay OA publishing fees ("Gold OA") -- if and when subscriptions eventually become unsustainable -- is hence the money that institutions are currently spending on subscriptions. In other words,

while peer review is still being paid for in full by subscriptions, there is no excuse for holding the author's final draft -- and research uptake, impact and progress -- hostage to publishers' current M.O.

What the research community needs, urgently, is free online access (Open Access, OA) to its own peer-reviewed research output. Researchers can provide that in two ways: by publishing their articles in OA journals (Gold OA) or by continuing to publish in non-OA journals and self-archiving their final peer-reviewed drafts in their own OA Institutional Repositories (Green OA). OA self-archiving, once it is mandated by research institutions and funders, can reliably generate 100% Green OA. Gold OA requires journals to convert to OA publishing (which is not in the hands of the research community) and it also requires the funds to cover the Gold OA publication costs. With 100% Green OA, the research community's access and impact problems are already solved. If and when 100% Green OA should cause significant cancellation pressure (no one knows whether or when that will happen, because OA Green grows anarchically, article by article, not journal by journal) then the cancellation pressure will cause cost-cutting, downsizing and eventually a leveraged transition to OA (Gold) publishing on the part of journals. As subscription revenues shrink, institutional windfall savings from cancellations grow. If and when journal subscriptions become unsustainable, per-article publishing costs will be low enough, and institutional savings will be high enough to cover them, because publishing will have downsized to just peer-review service provision alone, offloading text-generation onto authors and access-provision and archiving onto the global network of OA Institutional Repositories. Green OA will have leveraged a transition to Gold OA.

Stevan Harnad

Harnad, S. (2011)

What Is To Be Done About Public Access to Peer-Reviewed Scholarly Publications Resulting From Federally Funded Research? (

Response to US OSTP RFI).

Harnad, S. (2011)

Open Access Is a Research Community Matter, Not a Publishing Community Matter.

Lifelong Learning in Europe, XVI (2). pp. 117-118.

Harnad, S. (2010)

The Immediate Practical Implication of the Houghton Report: Provide Green Open Access Now.

Prometheus, 28 (1): 55-59.

Harnad, S. (2007)

The Green Road to Open Access: A Leveraged Transition. In: (A. Gacs. Ed.)

The Culture of Periodicals from the Perspective of the Electronic Age pp. 99-105, L'Harmattan.

Houghton, J.W. & Oppenheim, C. (2009)

The Economic Implications of Alternative Publishing Models.

Prometheus 26(1): 41-54:

Houghton, J.W., Rasmussen, B., Sheehan, P.J., Oppenheim, C., Morris, A., Creaser, C., Greenwood, H., Summers, M. and Gourlay, A. (2009).

Economic Implications of Alternative Scholarly Publishing Models: Exploring the Costs and Benefits, London and Bristol: The Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC)

Houghton, J.W. and Sheehan, P. (2009)

Estimating the potential impacts of open access to research findings,

Economic Analysis and Policy, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 127-142.