Sunday, August 7. 2005

A Keystroke Koan For Our Open Access Times

[This is an updated version of a posting to the American Scientist Open Access Forum on Tuesday, 14 October 2003.]When Harold Varmus's very timely and influential 1999 Ebiomed Proposal (a pot-pourri of ideas about publishing, journals, archiving, peer-review, and what would eventually come to be called "Open Access [OA]") elicited staunch opposition from its foes and constructive criticism from its friends -- but very little in the way of OA -- it led to the creation of the Public Library of Science (PLoS), whose first action was to launch an Open Letter, signed by 34,000 biologists worldwide, threatening to boycott their journals if they did not make their contents OA (within 6 months of publication).

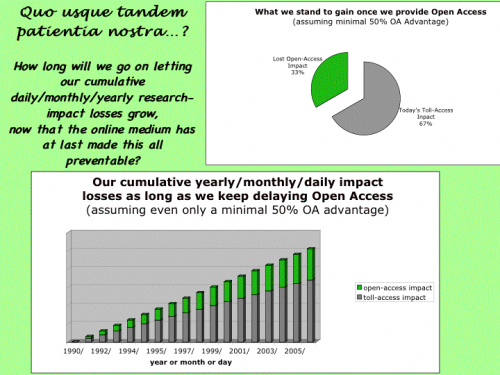

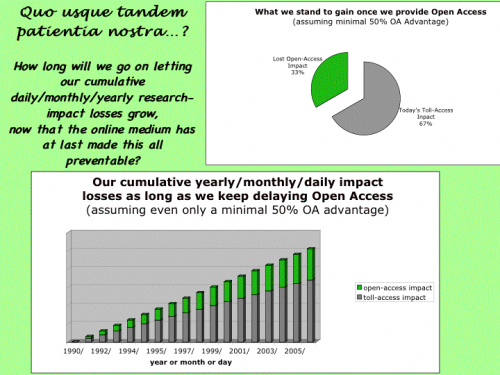

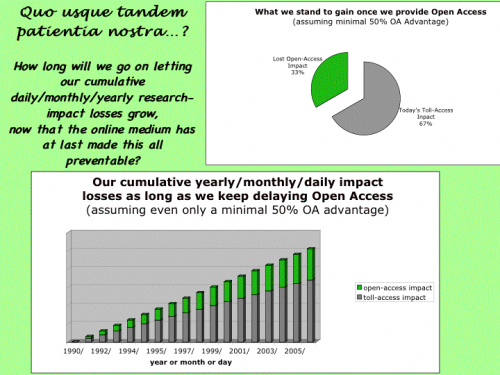

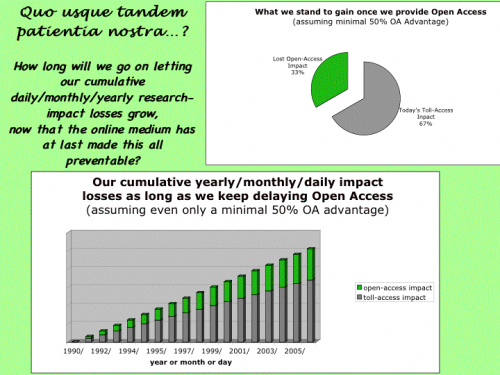

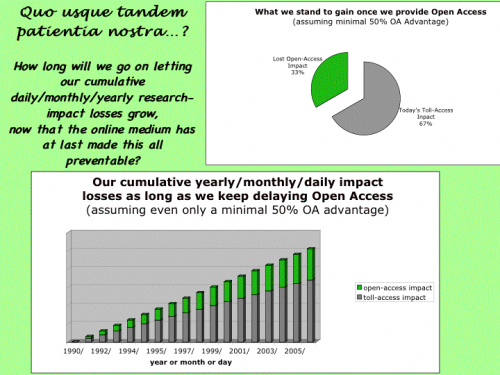

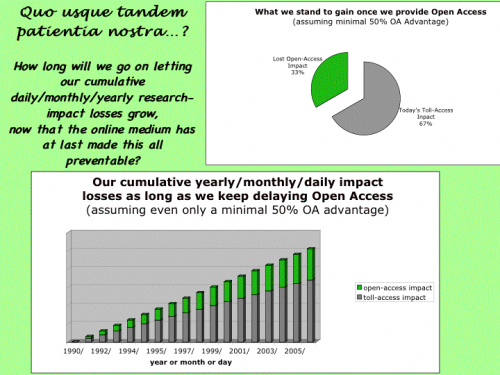

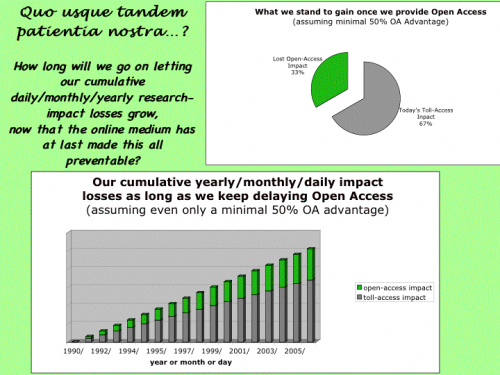

Now SUPPOSE that -- in addition to performing the keystrokes required to sign the 2001 PLoS open letter (pledging to boycott journals unless they become OA journals), each of the 34,000 PLoS signatories had also performed (or deputized a librarian, secretary or student to perform for them) the few further keystrokes it would have required to make just one of their own year-2001 articles OA by self-archiving it, free for all, on the web.Is there not a note of inconsistency in this? Researchers feel they need and want OA enough to demand it from their journals, even threatening (rather idly, as it turns out to have been a bluff) to stop submitting to and peer-reviewing for the journals that decline to give them the OA they need and want so much. The benefits of OA are clearly demonstrated by the objective evidence for the dramatic citation impact advantage provided by OA, so the needing and wanting have an unassailable objective basis: But do they have an equally unassailable subjective basis, if the needing and wanting are not sufficient to induce researchers to perform (or commission) for themselves the few keystrokes that are the only thing standing between them and 100% OA?

THEN the number of OA articles (34,000) resulting from just that minimal act would already have doubled (to 60%) the percentage of OA articles (34%) among the approximately 55,000 Biology articles indexed by ISI in 2001; it would also have exceeded the total number of articles published by both BioMed Central and PLoS journals from 2001 to the present (c. 20,000)

And all at the cost of only a few keystrokes more per article than what it cost to sign the PLoS petition.

Yet the only thing researchers did in 2001 was to sign the PLoS Open Letter demanding that their journals give them OA. They then waited, passively, for the journals to comply with their demand for OA. [Most journals did not comply directly; of the 24,000 peer-reviewed journals that exist in 2005, only about 1700 of them (7%) have converted to (or already were) OA ("gold") journals; however, since 2001 over 90% of journals have also gone on to give author self-archiving their "green light" in response to researchers' expressed wish for OA.] Yet today most researchers still seem ready to keep on waiting, passively, for more OA journals to be created or converted, one by one. Meanwhile spontaneous self-archiving continues to hover at between 5-25%, depending on the field and year.

Researchers themselves have hinted at the resolution to this koan: Yes, they need and want OA. But there are many other demands on their time too, and they will only perform the requisite keystrokes if their employers and/or funders require them to do it, just as it is already their employers and funders who require them to do the keystrokes to publish (or perish) in the first place. It is employers and funders who set researchers' priorities, because it is employers and funders who reward researchers' performance. Today, about 15% of research is self-archived spontaneously but 95% of researchers sampled report that they would self-archive if required to do so by their employers and/or funders: 81% of them willingly, 14% reluctantly; only 5% would not comply with the requirement. And in the two objective tests to date of this self-reported prediction, both have fully confirmed it, with over 90% self-archiving in the two cases where it was made a requirement (Southampton-ECS and CERN).

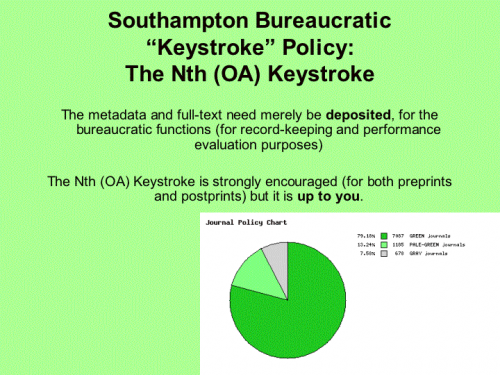

So an employer/funder self-archiving mandate is obviously what is missing to resolve the koan. But what exactly needs to be mandated? Only the keystrokes for depositing the final draft plus the OAI metadata of the article in the author's Institutional Repository (IR) immediately upon acceptance for publication, along with the strong encouragement to set access-privileges as "OA" (full-text access open webwide). Access to over 90% of these articles can already be set as OA with the blessing of their publishers. The rest can be set to IR-internal access (for institutional employees, employers and funders) for the time being, but their metadata (author, title, journal, date, abstract, keywords) will still be as visible to all searchers and surfers webwide as those of the 90% that are already OA, allowing would-be users to email the author to request an eprint. Emailing eprints can bridge the gap until either the remaining 10% of journals give self-archiving their blessing or the author tires of doing the superfluous keystrokes to email the eprints and simply does the last keystroke to set access at OA. Either way, mediated OA will already be providing effective 100% OA as of the implementation of the keystroke-policy.

Such an immediate-deposit ("keystroke") policy -- leaving no loopholes for any exceptions or delays -- is what Research Councils UK (RCUK) needs to mandate. The rest of the planet will follow suit. And Nature will take care of the rest.

Stevan Harnad

" Why price boycott is the wrong strategy" -- (Feb. 2000)

" Petitions, Boycotts, and Liberating the Refereed Literature Online" -- (Oct 2000)

Friday, August 5. 2005

NEEDED: MORE OA CONTENT (100%), NOT MORE FUNCTIONALITY FOR THE SPARSE EXISTING OA CONTENT (20%) SO FAR

In: Re-engineering the Open Access Movement I: Addressing What is Currently Missing,Sherif Masoud (SM) wrote:

The objective would seem to be to raise that 20% to 100% as soon as possible, rather than to try to squeeze more usage and functionality out of the impoverished 20% that exists to date. For this, I would say that 100% of effort should be expended on inducing researchers to make 100% of their research articles OA.

This perception is wrong, and the number of keystrokes and minutes involved in doing one moderately intensive online search are comparable to the number of keystrokes and minutes involved in making one of your own articles OA by self-archiving it (Carr & Harnad 2005).

Yet not even the repeated demonstrations of the dramatic increase in citation impact for articles made OA by self-archiving (Brody & Harnad 2004) has yet proved sufficient to persuade nearly enough authors to self-archive .

The solution is clear, and has been clearly stated by authors themselves, in their responses to two international, interdisciplinary JISC surveys showing that most authors say they will not self-archive until and unless their employers and/or their research-funders require it -- but if/when they do require it, over 94% of authors say they will do it (81% of them willingly, 14% reluctantly, with only 5% saying they still will not do it).

So what is urgently needed worldwide today is definitely not a diversion of effort toward enhancing user functionality for the sparse 20% OA content that already exists, but a concerted effort to get researchers' employers and funders to require OA self-archiving. Research Councils UK looks as if it will adopt a policy of requiring OA self-archiving at the end of this month, and if they do, it is very likely that other institutions worldwide will follow suit. The blueprint for the policy requirement is already there:

Diverting efforts instead toward increasing the functionality of the sparse OA content that already exists would simply delay still longer the optimal, inevitable, and already long overdue outcome: 100% OA. That (not something else) is the 100% doable thing that still remains 80% undone. That (not something else) is what needs doing. Endless diversions have kept it undone far too long already. Please, let us not keep finding more diversions. OA provision needs to be mandated by researchers' institutions and funders: "that is all ye know on earth, and all ye need to know."

SM: "I suggest that the efforts of the open access (OA) advocates be utilized in a different way from the current one so that the open access potential successes are expedited. I propose that roughly one third of such efforts be directed towards increasing the use of current OA publications."I am not sure whose efforts are being targeted here (OA advocates, libraries, publishers, researchers, universities, research-funders) nor how much effort any of these is actually expending for OA today. But the fact is that about 20% of research output is being made OA today (5% by publishing it in OA journals, 15% by self-archiving it in OA archives).

The objective would seem to be to raise that 20% to 100% as soon as possible, rather than to try to squeeze more usage and functionality out of the impoverished 20% that exists to date. For this, I would say that 100% of effort should be expended on inducing researchers to make 100% of their research articles OA.

SM: "Using the OA resources more extensively will result in higher awareness and impact for the OA publications. This will lead to readers (users) and authors demanding more OA publications and repositories. This increased demand will result in higher OA supply in the form of OA journals and repositories, which is the end goal of the OA movement."This is what I too thought 6 years ago, when OAI and OpCit and Citebase and OAister were launched: Surely as the research community experiences the power and utility of OA as users (consumers) they will translate their satisfaction into their behaviour as authors (providers). But that didn't happen -- partly because of the limited functional potential of such sparse coverage (20%), no matter how deluxe, and partly because of the (wrong) perception that much more effort is entailed in being an OA provider rather than just an OA consumer.

This perception is wrong, and the number of keystrokes and minutes involved in doing one moderately intensive online search are comparable to the number of keystrokes and minutes involved in making one of your own articles OA by self-archiving it (Carr & Harnad 2005).

Yet not even the repeated demonstrations of the dramatic increase in citation impact for articles made OA by self-archiving (Brody & Harnad 2004) has yet proved sufficient to persuade nearly enough authors to self-archive .

The solution is clear, and has been clearly stated by authors themselves, in their responses to two international, interdisciplinary JISC surveys showing that most authors say they will not self-archive until and unless their employers and/or their research-funders require it -- but if/when they do require it, over 94% of authors say they will do it (81% of them willingly, 14% reluctantly, with only 5% saying they still will not do it).

So what is urgently needed worldwide today is definitely not a diversion of effort toward enhancing user functionality for the sparse 20% OA content that already exists, but a concerted effort to get researchers' employers and funders to require OA self-archiving. Research Councils UK looks as if it will adopt a policy of requiring OA self-archiving at the end of this month, and if they do, it is very likely that other institutions worldwide will follow suit. The blueprint for the policy requirement is already there:

The end goal is 100% OA, and the two roads to 100% OA are the "golden" road of publishing articles in OA journals or the "green" road of self-archiving in OA archives all articles published in non-OA journals. Neither informing researchers about the benefits of OA nor showing them how to derive those benefits is enough: Their employers and funders also need to require OA provision (just as they already require publishing itself: "publish or perish") for the sake of maximizing individual and institutional research impact and maximizing the return on research funders' investment in research, in terms of research uptake, usage, impact and progress.RCUK Proposed Policy RequirementSM: "Reviewing a few Internet publications on open access [1], I found that almost every open access (OA) advocate's efforts are in one of two directions: analyzing, understanding, and explaining that OA is much more useful than closed access for everybody (except maybe for giant publishers) or promoting the foundation of OA serials / repositories and publishing in them. While the domination of OA serials and repositories form the end goal of the OA movement, I believe the current direction of efforts is not the best one to achieve that end goal in the fastest way possible. Re-engineering the open access movement to address what is currently missing can be very useful in expediting the domination of open access."

UK Select Committee Proposed Policy Requirement

Berlin-3 Proposed Policy Requirement

Registry of Institutional OA Self-Archiving Policies

Diverting efforts instead toward increasing the functionality of the sparse OA content that already exists would simply delay still longer the optimal, inevitable, and already long overdue outcome: 100% OA. That (not something else) is the 100% doable thing that still remains 80% undone. That (not something else) is what needs doing. Endless diversions have kept it undone far too long already. Please, let us not keep finding more diversions. OA provision needs to be mandated by researchers' institutions and funders: "that is all ye know on earth, and all ye need to know."

SM: "I propose that only a certain part of the OA advocates' efforts be directed towards supporting the extensive use of OA publications. I don't mean a total change; I am saying that roughly two thirds of the efforts should stay in the current directions, but the rest should be in the direction of promoting the extensive use of OA publications. "There is no point promoting the extensive use of sparse content! What is missing is the content, not the usage or the functionality. The greater usage of OA content is already fully demonstrated by its already-existing citation advantage of 50%-250+% as well its usage (download) advantage. Those few cows (20%) cannot be milked more fully! We need more cows (100%).

SM: "Amplifying the use and citations of the OA publications will result in higher awareness and impact for the OA literature. As the impact and awareness keep amplifying, the readers (users) and authors' demand for OA literature (serials and repositories) will intensify. This increased demand will result in higher OA supply (in the form of OA journals and repositories), which is the end goal of the OA movement."But the usage and citations of OA articles are already greatly amplified; this has been happening for years, and has lately been demonstrated repeatedly, in field after field. These findings are useful, and will certainly persuade some more authors to provide OA to their work, but not nearly enough. What is needed is an OA-provision requirement from researchers' employers and funders. The employers and funders, in turn, are the ones who are being persuaded to adopt the policy of requiring OA-provision by the already amply abundant evidence that OA enhances research usage and impact. Is a 50%-250% advantage not already advantage enough?

SM: "So the question that rises is "how to promote the use of OA publications"? Well, the degree of using and citing OA literature is proportional to how easy it is to access that literature. Therefore OA advocates, both librarians and academic experts, have vital roles to play here. Librarians, the guardians of libraries, should be natural OA advocates because OA helps them mitigate the serials crisis. Hence, they should mine for OA resources all over the Internet and present it to their academic communities in an easy to use way."But Sherif, the ease-of-access effect and the evidence for it are already there! (And although librarians are great allies to the OA movement, it is a great mistake to imagine that the rationale for researchers providing OA is to mitigate the serials crisis! The rationale is to maximize research usage, impact and progress.)

SM: "Innovative techniques are expected to achieve good results. I mean that the starting point is: the Internet is there containing all the open access publications and the search engines are there giving millions of page results to searchers. Of course a starting point like that --if it is also the final point-- is not very promising. Innovatively, the final point, could be a website that integrates all the sources in an institution's library and the Internet (e.g. open access journals) with a scope encompassing a researcher's specific point of research (e.g. gear design in mechanical engineering)."This was the reason the OAI interoperability protocol was designed in 1999. Please have a look at OAister and Citebase and Google Scholar. The functionality is already there (and being heavily used). What is missing is 80% of the target content!

SM: "That's only one innovative example; I am sure there are many creative ways in which librarians can catalog Internet OA content to make them easy to use. Let's start thinking that not properly guiding the library patrons to available OA resources is analogous to having very generous donators that donate lots of publications to a library and also pay for storing them to be only left in the warehouse without being added to the library catalog (although the keys of the warehouse are available for patrons upon request for digging on their own)."Sherif, I'm afraid these are rather old-fashioned views on functionality in the online age. What users need today is not more cataloguing or help from librarians: They need more OA content (preferably OAI-compliant): 80% more. That's all. The rest will take care of itself.

SM: "On the other hand, as experts in precise fields of research, academic OA advocates are also urged --individually or collaboratively-- to form Internet research guides on their fields of studies. "Why? Why produce guides to a sparse 20% of content? And why have guides at all, when OAI full-text content can be inverted and searched boole/google-style, with the help of citation-links and -metrics as well as similarity-metrics? What's missing today, and urgently needed, is more OA content, not more OA visibility/classification/navigation resources.

SM: "Another point, the design of such Internet research guides should always be user-centered. That means for the user (researcher or reader) a closed access database (e.g. only table of contents, abstracts, or even pay-per view) could be very useful along with OA publications."Anyone who wishes to build value-added services on top of OA content is welcome to do so -- but first we need the OA content, otherwise there is precious little to add the value to.

SM: "I mean finally what will get the impact and awareness is open access, but for the research guides to be successful in attracting researchers they have to be hybrid in order to fulfil all of the researchers' requirements. Along with that, the benefits of open access should always be advertised, so that researchers not only know about them practically (when using the OA movement research guides) but also understand the theory behind them (how this is happening). Needless to say, the OA advertising should never annoy or disturb the users; it should come naturally. Moreover, it will be easy to recruit at least some of the users of those research guides to the OA movement, to advocate for open access themselves later. To illustrate what I am suggesting, [2] represents an attempt of creating an Internet research guide that integrates both OA and other forms of learning sources, coupling that to non-destructive OA advertising."There has been a modest flow from OA usage/consumption to OA provision, indeed that is part of the source of the existing 20% OA content. But it is clear that nowhere near enough OA content can be expected (within the visible future) via that slow and indirect route. Something far more substantive is needed to end the already absurdly long delay in reaching 100% OA, and that something is what authors themselves have said they would need in order to induce them to provide OA: a policy of requiring it by their employers and/or funders.

SM: "To optimally achieve open access in scholarly publishing, the scope of efforts should encompass every possible way of open access (not only scholarly publishing)."OA is not OA-in-scholarly-publishing, it is OA-to-scholarly-publications. OA is no more a reform of scholarly publishing than it is a remedy for the serials crisis. It is a way for researchers to maximize the usage and impact of their own research publications (whether the golden way, by publishing them in OA journals, or the green way, by publishing them in non-OA journals but also self-archiving them in OA Archives; Harnad, Brody, Vallieres, Carr, Gingras, Oppenheim, Stamerjohanns & Hilf 2004).

SM: "I propose that the efforts in this direction be at all levels (e.g. for students, researchers, and practitioners). There are mutual interactions among those groups, so the more open access is appreciated among, for example, college students, the more it will be among researchers. One reason is that the students of today are the researchers of the near future. Further, creative traditional print books on open access are needed. The traditional books still have their audience that respect them and see them as almost the only authority in any topic. The open access movement needs to address such an audience."If we wait for students to come of age in order to reach 100% OA we are waiting absurdly long, and needlessly losing a great deal of potential research impact and progress in the meanwhile. Researchers are happy for students and practitioners to read and use their research, but they are writing it mainly for their fellow researchers (that's what their careers and funding depend on): It is their fellow researchers who can build on their research, thereby extending its impact. Researchers will not be persuaded to provide OA by evidence of enhanced usage by students (or practitioners, in that minority of research fields where there even are practitioners at all!); after all, they are not yet even sufficiently persuaded by the evidence of enhanced usage and impact by and for their fellow-researchers! The persuasion will have to come from the same source that persuades them to publish in the first place (rather than put their research findings in a desk-drawer and move on to the next piece of curiosity-driven, solipsistic research): the persuasion will have to come from their employers and funders.

SM: "A proposal for re-engineering the open access movement by re-directing the current efforts of the OA advocates was presented. It is hoped that this proposal will raise a lot of discussions, ultimately resulting in substantial improvements"If everyone who wishes to invest some time and effort into promoting OA were to invest it, first, into (1) self-archiving 100% of their own articles, and, second, into (2) persuading their own institution to adopt a policy of requiring self-archiving for 100% of its research article output, that time and effort would be immeasurably better spent than investing it in trying to enhance the functionality of the impoverished 20% OA content we have today.

Monday, July 25. 2005

WILEY'S NIH POLICY

The (anonymized) query below concerning Wiley's NIH policy is in error, so I am preceding it by a correction:

Author/institution self-archiving is and always was the 100% certain path to 100% OA. 100% self-archiving is (and always was) completely within the hands of the research community. And it is unstoppable. The fact that we are not there yet is definitely not the fault of publishers but of the sluggishness and slow-wittedness of the research community (which is also it's primary beneficiary).

But it does look as if we are coming to our senses at last... The RCUK policy may prove to be the decisive step.

Stevan Harnad

From: [identity deleted]

To: American Scientist Open Access Forum

Subject: Wiley Publishers deposit in PMC

This could be a way of publishers encouraging authors not to deposit - ie the publisher will do it, but creates an embargo because it appears that the publisher deposited article will not be available until 12 months after publication? Do you know if other publishers are following this policy? The National Institutes of Health Public Access Initiative

Response and Guidance for Journal Editors and Contributors

Notice of Wiley's Compliance with NIH Grants and Contracts Policy

Recently, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has requested that its grantees submit copies of manuscripts upon their acceptance for publication to PubMedCentral (PMC), a repository housed within the National Library of Medicine..

On behalf of our authors who are also NIH grantees, Wiley will deposit in PMC at the same time that the article is published in our journal the peer-reviewed version of the author's manuscript. Wiley will stipulate that the manuscript may be available for "public access" in PMC 12 months after the date of publication.

By assuming this responsibility, Wiley will ensure that authors are in compliance with the NIH request, as well as make certain the appropriate version of the manuscript is deposited.

When an NIH grant is mentioned in the Acknowledgments or any other section of a manuscript, Wiley will assume that the author wants the manuscript deposited into PMC, unless the author states otherwise. The author can communicate this via email, or a note in the manuscript. The version of the manuscript that Wiley sends to PMC will be the accepted version, i.e. the version that the journal's Editor-in-Chief sends to Wiley for publication.

Wiley will notify the author when the manuscript has been sent to PMC.

Because Wiley is taking the responsibility for sending the manuscripts to PMC, in order to ensure an orderly process, authors should not deposit Wiley articles to PMC themselves. Authors should not make corrections to their Wiley-deposited manuscripts in PMC.

Wiley reserves the right to change or rescind this policy.

For further information, please get in touch with your editorial contact at Wiley, or see the NIH Policy on Public Access.

(1) The new Wiley NIH policy below is specific to Wiley's compliance with the NIH public access policy, which invites NIH fundees to deposit their NIH-funded papers in PubMed Central (PMC) -- a third party central archive (i.e., neither the author's institutional archive nor the publisher's archive).Just as it would be a good idea if publishers were to refrain from speculating about doomsday scenarios (about catastrophic cancellations as a result of self-archiving) for which there is zero positive evidence and against which there is a good deal of negative evidence, it would be a good idea if librarians and OA advocates were to refrain from speculating about sinister scenarios involving NIH-inspired publisher back-sliding on self-archiving policy, for which there is and continues to be exactly one single isolated example -- Nature Publishing Group -- and even that merely a case of back-sliding from a postprint full-green policy to a preprint pale-green policy (which is of next to no consequence, as one can have 100% OA with corrected preprints).

(2) The Wiley NIH policy is to deposit the author's paper in PMC on the author's behalf.

(3) The Wiley NIH policy has no bearing whatsoever on 1st-party self-archiving by the author in the author's own institutional repository; Wiley's policy on immediate author/institution self-archiving is and continues to be green.

Author/institution self-archiving is and always was the 100% certain path to 100% OA. 100% self-archiving is (and always was) completely within the hands of the research community. And it is unstoppable. The fact that we are not there yet is definitely not the fault of publishers but of the sluggishness and slow-wittedness of the research community (which is also it's primary beneficiary).

But it does look as if we are coming to our senses at last... The RCUK policy may prove to be the decisive step.

Stevan Harnad

Date:Thu, 21 Jul 2005 12:12:15 +010

From: [identity deleted]

To: American Scientist Open Access Forum

Subject: Wiley Publishers deposit in PMC

This could be a way of publishers encouraging authors not to deposit - ie the publisher will do it, but creates an embargo because it appears that the publisher deposited article will not be available until 12 months after publication? Do you know if other publishers are following this policy? The National Institutes of Health Public Access Initiative

Response and Guidance for Journal Editors and Contributors

Notice of Wiley's Compliance with NIH Grants and Contracts Policy

Recently, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has requested that its grantees submit copies of manuscripts upon their acceptance for publication to PubMedCentral (PMC), a repository housed within the National Library of Medicine..

On behalf of our authors who are also NIH grantees, Wiley will deposit in PMC at the same time that the article is published in our journal the peer-reviewed version of the author's manuscript. Wiley will stipulate that the manuscript may be available for "public access" in PMC 12 months after the date of publication.

By assuming this responsibility, Wiley will ensure that authors are in compliance with the NIH request, as well as make certain the appropriate version of the manuscript is deposited.

When an NIH grant is mentioned in the Acknowledgments or any other section of a manuscript, Wiley will assume that the author wants the manuscript deposited into PMC, unless the author states otherwise. The author can communicate this via email, or a note in the manuscript. The version of the manuscript that Wiley sends to PMC will be the accepted version, i.e. the version that the journal's Editor-in-Chief sends to Wiley for publication.

Wiley will notify the author when the manuscript has been sent to PMC.

Because Wiley is taking the responsibility for sending the manuscripts to PMC, in order to ensure an orderly process, authors should not deposit Wiley articles to PMC themselves. Authors should not make corrections to their Wiley-deposited manuscripts in PMC.

Wiley reserves the right to change or rescind this policy.

For further information, please get in touch with your editorial contact at Wiley, or see the NIH Policy on Public Access.

Tuesday, July 19. 2005

PROMOTING INSTITUTIONAL OA SELF-ARCHIVING

On Mon, 18 Jul 2005, Minh Ha Duong wrote in the American Scientist Open Access Forum:

But it is the institututional self-archiving mandate itself that is the most effective way of generating self-archiving, as can be seen by comparing archive growth and size for those institutions that have no institutional self-archiving policy (1), a policy o recommending but not requiring self-archiving (2), and a policy of requiring self-archiving (3):

The only two institutions in the world so far that have a policy of requiring self-archiving (3) -- Southampton ECS and CERN -- have each (ECS, CERN) achieved a 90% self-archiving rate for current research output, exactly as the above JISC Survey findings indicated. The archives of institutions with only recommended self-archiving (2) are filling less, and less quickly; those of institutions with no self-archiving policy at all even less so.

For (2) and (3) see the Registry of Institutional OA Policies. For (1) see the Registry of Institutional OA Archives.

Stevan Harnad

I want to sell to the higher-ups at my national research institution (CNRS) the idea of an open evangelization mission to promote open archiving. I think that just saying "now everybody on the payroll should archive" is likely not to be efficient. We are especially interested in the department of Social Sciences and Humanities, which comprises a few hundred lab or research teams.First, do not underestimate the potential impact of a mandate:

But it would also help to show researchers why they should self-archive: to maximise research usage and impact. See especially the findings in Social Sciences (Sociology, Economics)."[This] international, cross-disciplinary [author] study on open access had 1296 respondents:... The vast majority of authors (81%) would willingly comply with a mandate from their employer or research funder to deposit copies of their articles in an institutional or subject-based repository. A further 13% would comply reluctantly; 5% would not comply with such a mandate." Swan, A. (2005) Open access self-archiving: An Introduction. JISC Technical Report.

What do you think? Do you know of any instances of such institutional effort to promote OA? How did they go about it, and with what results?On how institutions actually promote OA self-archiving, I'm afraid I have no data. -- Postings from those institutions that do promote self-archiving, to let us know how they are promoting it, would be most welcome. -- The OSI Eprints Handbook as well as the Self-Archiving FAQ suggest ways to implement and promote self-archiving.

Minh Ha Duong Chargé de recherches au CIRED, CNRS

But it is the institututional self-archiving mandate itself that is the most effective way of generating self-archiving, as can be seen by comparing archive growth and size for those institutions that have no institutional self-archiving policy (1), a policy o recommending but not requiring self-archiving (2), and a policy of requiring self-archiving (3):

The only two institutions in the world so far that have a policy of requiring self-archiving (3) -- Southampton ECS and CERN -- have each (ECS, CERN) achieved a 90% self-archiving rate for current research output, exactly as the above JISC Survey findings indicated. The archives of institutions with only recommended self-archiving (2) are filling less, and less quickly; those of institutions with no self-archiving policy at all even less so.

For (2) and (3) see the Registry of Institutional OA Policies. For (1) see the Registry of Institutional OA Archives.

Stevan Harnad

Saturday, July 16. 2005

RESPONSE TO ALPSP RESPONSE TO RCUK POLICY PROPOSAL

This is a response to:

Preamble: One can hardly ask for a better argument against ALPSP's 2005 Response to RCUK than ALPSP's very own 2004 Report 'Principles of Scholarship-Friendly Journal Publishing Practice'

Here are some relevant quotes from that 2004 ALPSP Report:

(All plain italic display-quotes preceded by "ALPSP:" are from the 2005 ALPSP Response to the RCUK's proposed self-archiving mandate.)

"Dissemination of and access to UK research outputs." Response from the Association of Learned and Professional Society Publishers (ALPSP) to the RCUK [Research Councils UK] Position Statement on Open Access to Research Outputs. (2005)

Preamble: One can hardly ask for a better argument against ALPSP's 2005 Response to RCUK than ALPSP's very own 2004 Report 'Principles of Scholarship-Friendly Journal Publishing Practice'

Here are some relevant quotes from that 2004 ALPSP Report:

The needs of authors

Our own surveys (1,2) have shown that two needs are of equally great importance to authors: maximum dissemination of their work, and publication in the most prestigious journal possible.

1) Dissemination

1.1 Dissemination by the author

It is in publishers' as well as authors' interest to maximise access to authors' work. There are many good examples of author agreements which enable authors to retain the rights which are particularly important to them (3):

1.1.1 Posting of preprints

According to our own survey of 149 publishers, including all the leading players (4), nearly 50% of publishers have no problem with authors posting a preprint or submission version of their article on one or more of their own, their institution's or a disciplinary website or repository, although some impose certain conditions such as requiring a link to the published version (5). So far, experience in those (relatively few) fields -- such as high energy physics (6) - where such repositories are active suggests that there is little or no damage to subscription or licensing income from the research journals.

1.1.2 Posting of final version

Our survey (7) shows that over 60% of publishers allow authors to post the final, published version of their article on websites or repositories (8), some even providing the PDF for this purpose. Although some speculate that increasing use of OAI-compliant metadata will ultimately enable such posting to undermine subscription and licence income, this does not seem to be the case so far....

...

Conclusion

It is in publishers' interest to satisfy the needs of their authors, readers and institutional customers to the best of their ability; this entails paying close attention to what these communities are saying, and collaborating with them to develop new approaches as need arises. Scholarship-friendly publishers maximise access to and use of content; they also maximise its quality and, thus, prestige. It goes without saying that -- by one business model or another -- publishers need to make enough money to cover their costs and stay in business; but they recognise that institutions' funds are increasingly inadequate to purchase all the information required by users, and they welcome collaboration with their customers to find new approaches which might solve this dilemma.

(All plain italic display-quotes preceded by "ALPSP:" are from the 2005 ALPSP Response to the RCUK's proposed self-archiving mandate.)

ALPSP: "ALPSP encourages the widest possible dissemination of research outputs; indeed, this furthers the mission of most learned societies to advance and disseminate their subject and to advance public education. We understand the benefits to research of maximum access to prior work..."An excellent beginning!

ALPSP: "ALPSP recognises that maximising access must be done in ways which do not undermine the viability either of the peer-reviewed journals in which the research is published"No one would disagree with this either.

ALPSP: "Understandably, therefore, [publishers] may not wish their "value-added" version to be made freely available in repositories immediately on publication."Quite understandable, and self-archiving is accordingly not about the publisher's value-added version -- not the copy-editing, not the XML markup, not the publisher's PDF -- but only about the author's own preprint (unrefereed draft) and postprint (corrected final draft). That is what is to be made available, “freely and immediately, in repositories.”

ALPSP: "Even if the freely available version lacks some or all of the value added by the publisher, it may be treated as an adequate substitute by uninformed readers"The freely available version is intended for the use of those potential researcher/users worldwide whose institutions cannot afford access to the publisher's value-added version. It is accordingly a more than adequate substitute for informed users who do not have acccess to any other version at all!

ALPSP: "(and, indeed, by cash-strapped libraries). And any new model which has the potential to "siphon off" a significant percentage of otherwise paying customers will, understandably, undermine the financial viability of all these value-adding activities."Surely the financial viability of the values-added is determined by their market value. As long as the added values have a market value, they remain viable. All evidence to date is that the self-archived free versions co-exist peacefully with the publishers' value-added versions, serving as supplements for those who cannot afford access to the value-added version rather than substitutes for those who can:

Swan & Brown (2005): "[W]e asked the American Physical Society (APS) and the Institute of Physics Publishing Ltd (IOPP) what their experiences have been over the 14 years that arXiv has been in existence. How many subscriptions have been lost as a result of arXiv? Both societies said they could not identify any losses of subscriptions for this reason and that they do not view [self-archiving] as a threat to their business (rather the opposite -- in fact the APS helped establish an arXiv mirrorsite at the Brookhaven National Laboratory)." Swan, A. & Brown, S. (2005) Open access self-archiving: An author study. JISC Technical Report.ALPSP: "The National Institutes of Health in the USA has attempted to address this concern by delaying, for up to 12 months after publication, the point at which deposited material becomes freely accessible. The 12-month period was arrived at after considerable discussion with society and other publishers; it goes some way to addressing their fears about the impact on subscription and licence sales. Even the Wellcome Foundation, which has not consulted with publishers, recognises the need for a 6-month embargo."The NIH and Wellcome embargoes concern the date of deposit in a central NIH/Wellcome Archive, PubMed Central (PMC), in which the metadata and perhaps also the full-text will appear in an enhanced ("value-added') form added by PMC.

The RCUK mandate concerns the self-archiving of the author's own preprints and postprints -- by the author in the author's one institutional repository -- for the sake of maximising immediate research progress and impact.

Research impact and progress are certainly not maximised by imposing 6- or 12-month embargoes! The value-added publisher's version can wait, but research itself certainly cannot, and should not.ALPSP: "Although in some areas of physics, journals have so far coexisted with the ArXiv subject repository, some of our members in other disciplines already have first-hand evidence that immediate free access can cause significant damage to sales."It would be very helpful if we could see precisely what this "other" evidence is, and precisely what it is evidence of. As physics and computer science are the fields that have self-archived the most and the longest, and all of their evidence is for peaceful co-existence between the authors’ supplementary drafts and the publisher's value-added version, it would be very interesting to see what evidence, if any, exists to the contrary. But please do make sure that the putative evidence does address the issue, which is:How much (if at all) does author self-archiving reduce subscriptions?The evidence has to be specific to author self-archiving, anarchically, article by article. It cannot be based on experiments in which journals systematically make all of their own value-added contents free for all online, for that is not the proposition that is being tested, nor the policy being recommended by RCUK!ALPSP: "We therefore recommend that the Research Councils should respect the wish of some publishers to impose an embargo of up to a year (or, in exceptional cases, even longer) before self-archived papers should be made publicly accessible."RCUK should require immediate self-archiving of the author's own postprint drafts (and strongly encourage preprint self-archiving too) for the sake of immediate research usage, progress and impact. Access to the publisher's value-added version can be embargoed for as long as the publisher deems necessary.ALPSP: "It should be stressed that any restrictions are intended simply to ensure the continuing viability of the journals, which allow authors (under either copyright model) all the rights which our research indicates they require, including self-archiving"The message is clear: Authors can and should self-archive their own drafts ("inadequate" though these may be), immediately, for the sake of research progress. The publisher's value-added version can be subject to whatever restrictions publishers see fit to impose.ALPSP: "It seems to us both inappropriate and unnecessarily wasteful of resources to create permanent archives of versions other than the definitive published versions of articles."It is not at all clear why publishers should be concerned with what authors elect to do with their own "inadequate" versions, in the interests of research. Publishers' concern should surely be with their own definitive, value-added versions, not whatever else the research community elects to do to maximize research progress and impact.ALPSP: "[A] significant proportion (41%) of existing Open Access journals do not, in fact, cover their costs"It is not clear why the topic has been changed here to Open Access Journals: What the RCUK is requiring is self-archiving; it is not requiring publication in Open Access Journals.ALPSP: "while ALPSP supports the principles which underlie the RCUK policy, we believe that existing publishing arrangements go a long way towards meeting the first three principles, and that publishers' concerns about the potential negative impact [emphasis added] of self-archiving must be addressed."Existing publishing arrangements go a long way, but the RCUK policy goes the rest of the way, for the sake of all the potential researcher-users worldwide whose institutions cannot afford the publisher's value-added version, despite the existing publishing arrangements.

It is in order to put an end to the needless and costly loss of that potential positive impact on research that the RCUK self-archiving mandate has been formulated.

A Prophylactic Against the Edentation of the RCUK Policy Proposal

Pertinent Prior AmSci Topic Threads:"A Simple Way to Optimize the NIH Public Access Policy"On Mon, 4 Jul 2005, Sally Morris (Chief Executive, ALPSP) wrote (in the SPARC Open Access Forum:

"Please Don't Copy-Cat Clone NIH-12 Non-OA Policy!"

"Nature Back-Slides on Self-Archiving [Corrected] (2005)"

"Open Access vs. NIH Back Access and Nature's Back-Sliding"

SM: "It beats me how people can argue on the one hand that repositories are necessary to solve libraries' financial problems"If anyone is arguing for OA self-archiving in order to solve libraries' financial problems, they are certainly barking up the wrong tree. As we have argued over and over:"the journal-affordability problem and the article-access/impact problem are not the same" Harnad, S., Brody, T., Vallieres, F., Carr, L., Hitchcock, S., Gingras, Y, Oppenheim, C., Stamerjohanns, H., & Hilf, E. (2004) The Access/Impact Problem and the Green and Gold Roads to Open Access. Serials Review 30 (4) 2004Institutional repositories (and institutional self-archiving mandates) are necessary in order to maximise research access and impact, not in order to solve libraries' financial problems. Conflating the two has always been a fundamental mistake, both practical and conceptual, and one that has done nothing but lose us time (and research progress and impact), needlessly delaying the optimal and inevitable outcome (for research, researchers, their institutions and their funders): An OA self-archiving mandate has nothing to do with library financial problems. It is adopted by researchers' employers and funders in order to maximize their (joint) research impact.

(But I agree that if many others had not repeatedly made this unfortunate and common conflation, Sally could not have made her own specious argument by way of reply!)SM: "Stevan, I don't know what planet you live on (;-) but on Planet Earth the problem librarians are trying to address - and the reason for any enthusiasm for repositories or any other means of OA - is a shortage of funds"Sally, that might be the reason for librarians' (and library funders') enthusiasm for OA, but it is not the main reason for OA. The reason for OA is to maximise research impact, hence research progress and productivity. And the providers of OA are not and cannot be librarians (be they ever so enthusiastic): The only providers of OA are the researchers themselves. And the only reason that will persuade them (and their funders) to provide OA is that it maximizes their research impact.

So whereas both the publishing community and the library community are marginally implicated in OA (each can either help or hinder it) OA-provision itself is 100% in the hands of the OA-providers: the research community. It can and will be done only by and for them.

It is to the terrestrial research community that the RCUK mandate is addressed.SM: "and on the other [hand, how can people argue that self-archiving]... will not lead to increased subscription/licence cancellations and thus, ultimately to the collapse of journals"The argument that self-archiving can and will increase research impact substantially is based on objective fact, tested and demonstrated by (a) years of self-archiving and by (b) repeatedly-replicated objective comparisons of citation impact between self-archived and non-self-archived articles in the same journals and issues, across all fields.

The argument that self-archiving will lead to journal cancellations and collapse, in contrast, is not based on objective fact but on hypothesis. There are of course counter-arguments too, based on counter-hypotheses. but it is also a fact that all objective evidence to date is contrary to the hypothesis that self-archiving leads to journal cancellation and collapse.

When -- in reply to Sally's statement:SM: "Although in some areas of physics, journals have so far coexisted with the ArXiv subject repository, some of our members in other disciplines already have first-hand evidence that immediate free access can cause significant damage to sales."I asked Sally for that evidence, she has now replied:SM: "the evidence I've been given so far was in confidence"So apparently the world research community is to contemplate continuing to refrain from maximising its research impact -- despite the many-times replicated objective evidence that self-archiving can and does maximize research impact -- on the strength of confidence in a hypothesis about eventual journal wrack and ruin, based on confidential evidence, unavailable for objective evaluation.

(This kind of empty -- but ominous-looking -- hand-waving, by the way, is precisely the grounds on which the NIH self-archiving mandate was reduced to the toothless dictum it has become, sans requirement, sans immediacy, sans everything.)SM: "Incidentally, the NIH embargoes are slightly more complex than Stevan suggests - authors are encouraged to deposit papers immediately on acceptance; the embargo relates to the date when they are made publicly available; I chose my words with care! Wellcome on the other hand is, I understand it, talking about the date of deposit."Promptly "depositing" papers in NIH's PubMed Central (PMC) so that they can just sit there, inaccessible, for 12 months? That sounds exactly as pointless as it ought to sound to anyone who remembers, if ever so faintly, that what this was all about was maximising research access and impact (immediately). The objective was not to perform a symbolic central-depositing ritual followed by an arbitrary research-wasting gestation period, in which the document -- meant to supplement paid access for those would-be users who cannot afford it -- instead simply lies fallow, for absolutely no defensible reason, at the continuing cost of daily, weekly, and monthly research impact and progress, exactly as it had done before the dawn of the online/OA era at last made it possible to put an end to that gratuitous impact loss once and for all!

Sally is right, however, that the NIH policy is more complicated than merely being the empty "request" to deposit papers ("immediately"), only to wait 12 months for them to become accessible to their intended users (6 months for the marginally less unwelcome Wellcome Policy). It is also only a request to deposit them in PMC, rather than what it could and should have been, namely, a requirement to deposit them immediately in each researcher's own institutional repository (with NIH/PMC harvesting them centrally if/when they see fit).

That would have been a policy that actually maximized research access and impact, rather than locking in a gratuitous year of access/impact loss (with the whole thing merely optional rather than obligatory to boot -- and almost inviting publishers to back-pedal on their existing immediate-self-archiving policies... in the name of NIH-compliance !)

And now here is RCUK, proposing precisely the optimal policy for maximizing research access and impact, and here's Sally hoping to pull its teeth much the way NIH's were pulled!

Fortunately, there is a way the RCUK policy can be protected from unneeded and unwanted NIH-style dental work! The key would be that the RCUK mandates distributed, institutional self-archiving rather than NIH-style central archiving. Hence each author can decide for himself whether and when to set access to his own full-text as "Open Access" (OA) rather than just "Institution-internal Access" (IA). Both the full text and the metadata, however, must be deposited immediately in the fundee's own institional repository. Those keystrokes must be performed. The metadata of course always immediately become openly accessible to all, webwide. (There is not even the semblance of a juridical issue about the author's metadata!) But the single keystroke that determines whether access to the full-text is institutional or worldwide can be left to the author (with strong encouragement to make it OA as soon as possible).

With such a policy, there is no point in anyone (including ALPSP) lobbying RCUK about embargoes: RCUK has simply mandated the immediate keystrokes and strongly encouraged the Nth one ("OA"). And research is still leaps and bounds ahead as a result. For not only do over 90% of articles already have their journal's green light for the Nth keystroke, but for the less than 10% that don't, the author can, for the time being, simply respond to email eprint-requests for the full-text (based on the openly accessible metadata) by doing the further keystrokes needed to email out the postprint to each eprint-requester.

Eventually, of course, nature will take its course, the author will tire of the needless keystrokes, and will simply do the Nth keystroke to make his postprint OA (as the sensible authors will all do in the first place). (The long overdue transit to the optimal and inevitable has -- it is now patently obvious – always been just a keystroke problem all along. Once the keystrokes are mandated, nature can be safely trusted to pursue its optimal course forthwith, guided by the incentive of impact -- and prodded by the nuisance of eprint-requests!)

But the point is that in the meanwhile, it will not be possible to edentate (q.v.) the RCUK policy in the same way that the NIH policy managed to get itself so sadly disfigured. And all the keystrokes will get done.

(Sally is characteristically coy about coming out and saying whether she is for or against giving the publisher's green light to the immediate institutional self-archiving of the author's own "inadequate" [Sally's word] final revised draft: She is eloquent about its inadequacies, but rather evasive about whether she would be for authors [immediately] setting that Nth keystroke -- for that self-same inadequate full-text -- as OA, or merely IA!)

I close by re-quoting in full the call for evidence in support of Sally's rather alarmist hypothesis of doom and gloom:SH: “It would be helpful to see precisely what this "other" evidence is, and precisely what it is evidence of. As physics and computer science are the fields that have self-archived the most and the longest, and all of their evidence is for peaceful co-existence between the author's drafts and the publisher's value-added version, it would be very interesting to see what evidence, if any, exists to the contrary. But please do make sure that the putative evidence does address the issue:And, to repeat Sally's reply:“How much (if at all) does author self-archiving reduce subscriptions?“The evidence has to be specific to author self-archiving, anarchically, article by article. It cannot be based on experiments in which journals systematically make all of their own value-added contents free for all online, for that is not the proposition that is being tested, nor the policy being recommended by RCUK!”SM:"the evidence I've been given so far was in confidence"Amen.

Thursday, July 14. 2005

SPARC (EUROPE) ENDORSES RCUK OA POLICY; SSHRC (CANADA) ENDORSES OA

"Leading European Library Organization firmly supports Research Councils UK new open access policy. Policy that requires UK-funded research be deposited in openly accessible archives will strengthen increased investment in research.http://www.sparceurope.org/press_release/RCUK.htm

(Source: David Prosser)

Canada's Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) has "endorsed the principles of the Open Access movement -- promoting and sharing the results of the SSHRC-funded research with the public."http://www.sshrc.ca/web/about/council_reports/news_e.asp#3

(Source: Heather Morrison)

Tuesday, July 12. 2005

FOUR SEMINAL SWAN/BROWN JISC REPORTS ON OPEN ACCESS

Swan & Brown's second international, cross-disciplinary JISC Open Access Author Survey will, I am fairly certain, turn out to be a milestone and historic turning point in the worldwide research community's progress towards 100% Open Access.

The JISC findings were reported at the International Conference on Policies and Strategies for Open Access to Scientific Information, Beijing, China, June 22-24, 2005

(1-l) the longer full JISC version of the above 2005 author survey,

(2) the brand-new JISC Open Access Briefing Paper,

plus two versions each of Swan, Brown et al's two classic papers:

(3) the 2004 JISC survey (3-s) journal version and (3-l) full JISC version) and

(4) Swan et al's 2004/2005 report of JISC's strategic and cost/benefit analysis of institutional vs. central repository self-archiving (4-s) journal version and (4-l) full JISC version).

The JISC findings were reported at the International Conference on Policies and Strategies for Open Access to Scientific Information, Beijing, China, June 22-24, 2005

(1-s) Short introduction to 2005 OA Author Survey:See also:

Swan, A. (2005) Open access self-archiving: An Introduction. Technical Report, JISC, Key Perspectives Inc. [m1] [m2] [m3] [Presentation pdf] [Presentation ppt]

(1-l) the longer full JISC version of the above 2005 author survey,

(2) the brand-new JISC Open Access Briefing Paper,

plus two versions each of Swan, Brown et al's two classic papers:

(3) the 2004 JISC survey (3-s) journal version and (3-l) full JISC version) and

(4) Swan et al's 2004/2005 report of JISC's strategic and cost/benefit analysis of institutional vs. central repository self-archiving (4-s) journal version and (4-l) full JISC version).

Summary of 2005 author survey (emphasis added): This, our second international, cross-disciplinary author study on open access had 1296 respondents. Its focus was on self-archiving. Almost half (49%) of the respondent population have self-archived at least one article during the last three years. Use of institutional repositories for this purpose has doubled since our last study and usage has increased by almost 60% for subject-based repositories. Self-archiving activity is most extensive amongst those who publish the largest number o papers. There is still a substantial proportion of authors who are unaware of the possibility of providing open access to their work by self-archiving. Of the authors who have not yet self-archived any articles, 71% remain unaware of the option. With 49% of the author population having self-archived in some way, this means that 36% of the total author population (71% of the remaining 51%), has not yet been appraised of this way of providing open access. Authors have frequently expressed reluctance to self-archive because of the perceived time required and possible technical difficulties in carrying out this activity, yet findings here show that only 20% of authors found some degree of difficulty with the first act of depositing an article in a repository, and that this dropped to 9% for subsequent deposits. Another author worry is about infringing agreed copyright agreements with publishers, yet only 10% of authors currently know of the SHERPA/RoMEO list of publisher permissions policies with respect to self-archiving, where clear guidance is provided as to what a publisher permits. Where it is not known whether permission is required, however, authors are not seeking it and are self-archiving without it. Communicating their results to peers remains scholars' primary reason for publishing their work; in other words,researchers publish to have an impact on their field. The vast majority of authors (81%) would willingly comply with a mandate from their employer or research funder to deposit copies of their articles in an institutional or subject-based repository. A further 13% would comply reluctantly; 5% would not comply with such a mandate.

In a separate exercise we asked the American Physical Society (APS) and the Institute of Physics Publishing Ltd (IOPP) what their experiences have been over the 14 years that arXiv has been in existence. How many subscriptions have been lost as a result of arXiv? Both societies said they could not identify any losses of subscriptions [as a result of self-archiving] and that they do not view [it] as a threat to their business (rather the opposite -- in fact the APS helped establish an arXiv mirror site at the Brookhaven National Laboratory).

Saturday, July 9. 2005

APPLYING OPTIMALITY FINDINGS: CRITIQUE OF GRAHAM TAYLOR'S CRITIQUE OF RCUK SELF-ARCHIVING MANDATE

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.

Department of Electronics and Computer Science

University of Southampton

Highfield, Southampton

SO17 1BJ UNITED KINGDOM

phone: +44 23-80 592-388

fax: +44 23-80 592-865

harnad@ecs.soton.ac.uk

http://www.ecs.soton.ac.uk/~harnad/

SUMMARY: Graham Taylor, director of educational, academic and professional publishing at the Publishers Association, criticises the Research Councils UK (RCUK) proposal to require that the author of every published article based on RCUK-funded research must “self-archive” a supplementary “open access” version on the web so it can be freely read and used by any researcher worldwide whose institution cannot afford the journal in which it was published. The purpose of the RCUK policy is to maximise the usage and impact of research. Taylor argues that this may have an adverse affect on some journals. This critique of Taylor's critique points out that there is no evidence from 15 years of open-access self-archiving that it has had any adverse affect on journals and a great deal of evidence that it enhances research impact.

[All quotes are from Graham Taylor, "Don't tell us where to publish" Guardian: Research News, Friday July 1, 2005]

GT:"Repositories are probably a good idea... But should they be used as a means for "publication"? And what is "publication" exactly?"

No one is proposing that institutional open-access (OA) repositories (or archives) should be used as a means of publication. They are a means of providing supplementary access to the (final drafts of) peer-reviewed, published research articles -- for those would-be users whose institutions cannot afford the paid access to the official published versions.

RCUK is not telling its fundees "where to publish," but what else they must do with their published (and funded) research, in order to maximize its usage and impact, over and above publishing it in the best possible peer-reviewed journal ("publish or perish").

GT: "UK Research Councils (RCUK) [have proposed a] policy [that] requires that funded researchers must deposit in an appropriate e-print repository any resultant published journal articles"

Correct. Notice that it says to "deposit" published journal articles, not to "publish" them. (To publish a published article would be redundant, whereas to provide a free-access version for those who cannot pay would merely ensure that the article's impact was more abundant.)

GT: "Publication involves a great deal more than mere dissemination. After the peer review, the editorial added-value, the production standards, the marketing, the customer service... the certification process process is an essential endpoint for any research activity. How does the RCUK policy relate to this?"

It relates in no way at all. The value can continue being added, and the resulting product can continue being sold (both on-paper and online) to all those who can afford to buy it, exactly as before. The author's self-archived supplement is for those who cannot afford to buy the official published version.

Does Graham Taylor recommend instead that research and researchers should continue to renounce the potential impact of all those potential users worldwide who cannot afford access to their findings today, and should instead carry on exactly as they had in the pre-Web era (when the potential to maximize the usage and impact of their findings by providing open access to them online did not yet exist)? Why?

GT: "Mandating deposit as close to publication as possible will inevitably mean that some peer-reviewed journals will have to close down. "

This is a rather strong statement of a hypothesis for which there exists no supporting evidence after 15 years of self-archiving -- even in those fields where self-archiving reached 100% some time ago. In fact, all existing evidence is contrary to this hypothesis. So on what basis is Graham Taylor depicting this doomsday scenario as if it were a factual statement, rather than merely the counterfactual conjecture that it in fact is?

A recent JISC study conducted by Swan & Brown reported: "[W]e asked the American Physical Society (APS) and the Institute of Physics Publishing Ltd (IOPP) what their experiences have been over the 14 years that arXiv [e-print repository] has been in existence. How many subscriptions have been lost as a result of arXiv? Both societies said they could not identify any losses of subscriptions for this reason and that they do not view arXiv as a threat to their business (rather the opposite -- in fact the APS helped establish an arXiv mirror site at the Brookhaven National Laboratory)."

GT: "Why should inadequate and overstretched library budgets pay for stuff that is available for free?"

(1) In order to have the print edition

(2) In order to have the publisher's official online (value-added) version of record

GT: "Library acquisition budgets represent less than 1% of expenditure in higher education... for more than a decade, despite double digit growth in research funding. Publication and output management costs represent around 2% of the cost of research to our economy, yet RCUK appears to want to bring new costs into the system."

Interesting data, but what on earth do they have to do with what we are talking about here? We are talking about researchers increasing the impact of their own research by increasing the access to their own research -- in the online age, which is what has at last made this maximised access/impact possible (and optimal for researchers, their institutions, their funders, and for research progress itself).

We have already established that self-archiving the author's final draft of a published article is not publishing, that it is done for the sake of those potential users who cannot afford the published version, and that those who want and can afford the published version can and do continue to buy it. So why are we here rehearsing the old and irrelevant publishers' plaint about the underfunding of library serials budgets? No one has mentioned the librarians' counter-plaint about publishers' over-pricing of journals. So why not let sleeping dogs lie? They are in any case irrelevant to the substantive research issue at hand, which is: maximising research impact, by and for researchers.

GT: "We need a sustainable, scaleable system for publication, which means making a "surplus" in the process to invest for the future, to fund the activities of the learned societies, to fund the cost of capital... But deposit on publication can only cannibalise the very system that makes mandating deposit viable in the first place."

How did we get onto the subject of publishers' profit margins and investments, when the problem was needlessly lost research impact? Is researchers’ needlessly lost research impact supposed to be subsidising publishers' venture capital schemes?

GT: "And then there are the costs. Is the current system failing? If access is a problem, where is the evidence?"

The problem is needless loss of research impact, because not all of the potential users of a research finding are necessarily at an institution that can afford to subscribe to the journal in which it was published. The evidence that the paid-access version alone is not reaching all or even most of its potential users is the finding -- replicated in field after field -- that the citation impact of self-archived articles is 50%-300+% higher than that of non-self-archived articles (in the same journal and issue) -- in all fields analysed so far:

http://citebase.eprints.org/isi_study/

http://www.crsc.uqam.ca/lab/chawki/ch.htm

http://opcit.eprints.org/oacitation-biblio.html

Lost impact is the evidence that limited access is a problem. The web era has made it possible to put an end to this needlessly lost impact.

The system is not "failing" -- it is just extremely (and needlessly) sub-optimal in its access provision in the online age. In fact, the system is somewhat better today than it had been in the paper age, but far from the substantially better that it could and should be (and already is -- for the 15% of articles that already have a self-archived supplement of the kind the RCUK is now proposing to require for 100% of UK research article output).

[Food for thought: This needlessly lost research access and impact would still be a problem if journals were zero-profit and sold at-cost! There would still not be enough money in the world so that all research institutions could afford to purchase access to all the journals their researchers could conceivably need to use. A self-archived supplement would still be needed then, as it is now, to maximise impact by maximising access.]

GT: "Is funding repositories the right way to spend scarce funds? Maybe, for reasons other than publication, but isn't this a high risk strategy? So where is the impact assessment and the rigorous cost appraisal in the RCUK policy?"

(RCUK is not yet proposing to fund repositories; it is only proposing to require fundees to fill them – although also helping to fund institutional repositories’ minimal repository costs would not be a bad idea at all!)

It is not altogether clear to me, however, why Graham Taylor or the publishing community should be asking about how the research community spends its research funds! But as it’s a fair question all the same, here's a reply:

However research money is spent, the greater the usage and impact of the research funded, the better that money has been spent. And self-archiving enhances research impact by 50%-300+%. (There's your "impact assessment"!):

The output of one research-active university might range from 1000 to 10,000 or more articles per year depending on size and productivity. Researchers are employed, promoted and salaried – and their research projects are funded -- to a large extent on the basis of the usefulness and impact of their research. Research that is used more tends to be cited more. So citations are counted, as measures of usage and impact.

The dollar value (in salary and grant income) of one citation varies from field to field, depending on the average number of authors, papers and citations in the field; the marginal value of one citation also varies with the citation range (0 to 1 being a bigger increment than 30 to 31, since 60% of articles are not cited at all, 90% have 0-5 citations, and very few have more than 30 citations:

A still much-cited 1986 study estimated the "worth" of one citation (depending on field and range) at $50-$1300. (This dollar value has of course risen in the ensuing 20 years.)

The UK Research Assessment Exercise (RAE) ranks UK Universities according to their research productivity and provides a substantial amount of top-sliced research funding proportional to each university's RAE ranking. It turns out that this ranking, hence each university’s amount of funding, is largely determined by the university’s total citation count.

So there’s your “impact assessment and the rigorous cost appraisal” for the RCUK policy.

GT: "Worldwide, 2,000 journal publishers are publishing 1.8 million articles per year (and rising) in 20,000 journals. Remember the UKeU - £50m to attract 900 students? The House of Commons education select Committee concluded that supply-side thinking was to blame. Is the RCUK policy really based on demand and need, or is supply-side thinking creeping in again?”

What on earth is all of this about? RCUK is talking about maximizing the impact of UK research output by supplementing paid journal access with free author-provided access – access provided by and to researchers, for their own research output -- and we are being regaled by irrelevant figures about numbers of articles published worldwide per year, the UKeU distance learning schemes that flopped, and "supply-side" thinking! What is Graham Taylor thinking?

GT: "The RCUK policy is based on four principles that we... support... Our problem is that we harbour deep concerns that the proposals founded on those principles will bring unforeseen - and potentially irreversible - consequences that we will all live to regret."

In other words, the principles seem unexceptionable, but Graham Taylor has a doomsday scenario in mind to which he would like the research community to attach equal (indeed greater) weight, despite the absence of any supporting evidence, and despite the presence of a good deal of contrary evidence (see the Swan & Brown JISC report cited above).

GT: "Instead, we offer some principles of our own: sustain the capacity to manage and fund peer review; don't undermine the authority of peer reviewed journals; match fund access to funding for research; invest in a sustainable organic system based on surplus not grants."

Translation: Pour more money into paying for journals rather than requiring fundees and their institutions to supplement the impact of their own funded research by making it accessible for free to potential users worldwide who cannot afford to pay for access.

(But there is not remotely enough available money in the world to ensure that all would-be users have paid access to all the research they could use – even if publishers were to renounce all profits and sell their journals at-cost. That is why the web is such a godsend for research.)

GT: "Publishers will support their authors in making their material available through repositories, provided they are not set up to undermine peer-reviewed journals. We say to RCUK, by all means encourage experiments, but don't mandate. Don't force transition to an unproven solution."

You would not call a solution that (1) has proven across 15 years to enhance impact by 50%-300+% and that (2) has not generated any discernible journal cancellations -- even in fields where self-archiving reached 100% years ago -- a proven solution? And you would like RCUK to refrain from mandating it on the strength of your doomsday scenario, which has no supporting evidence at all, and only contrary evidence?

GT: "Whatever you do, make the true costs transparent. The paper backing up the policy makes little or no acknowledgement of what the learned societies and publishers have achieved over the last 10 years."

The proposal is to supplement the current system, not to replace it. The value of the system is already inherently acknowledged in the fact that it is the content of peer-reviewed journal articles to which RCUK proposes maximising access -- not something else in their stead.

GT: "This is not to say that the current system is perfect... but it's getting better fast... [R]ather than standing on principle... we should allow time for the evidence to make the case. [That is] the very basis... of research."

It is now over 25 years since the advent of the Net and the possibility of 100% self-archiving in FTP sites, 15 years since the advent of the Web and the possibility of 100% self-archiving on personal websites, and 6 years since the advent of the OAI protocol and the possibility of 100% self-archiving in distributed interoperable institutional repositories.

So far, 49% of journal-article authors report having spontaneously self-archived at least once. Yet only about 15% of annual articles are actually being systematically self-archived. In the most recent of the international author surveys commissioned by the UK JISC, researchers have indicated exactly what needs to be done to get most of them to self-archive systematically: Over 80% replied that they will not self-archive until and unless their employers or funders require them to do so; but if/when they do require it, they will self-archive, and self-archive willingly.

Graham Taylor seems to be suggesting instead:

“No, don't act on the basis of the existing evidence.Wait for what? How much longer? And Why?

Keep losing research impact.

Don't mandate self-archiving.

Wait.”

REFERENCES

Harnad, S. (1991) Post-Gutenberg Galaxy: The Fourth Revolution in the Means of Production of Knowledge. Public-Access Computer Systems Review 2(1):39 - 53.

Harnad, S., Carr, L., Brody, T. & Oppenheim, C. (2003) Mandated online RAE CVs Linked to University Eprint Archives: Improving the UK Research Assessment Exercise whilst making it cheaper and easier. Ariadne 35 (April 2003).

Okerson, A. & O'Donnell. J (1995) (Eds.) Scholarly Journals at the Crossroads; A Subversive Proposal for Electronic Publishing. Washington, DC., Association of Research Libraries, June 1995.