Tuesday, February 17. 2009

John Wiley on RoMEO and John the Baptist on Supererogation

SUMMARY: Publishers are increasingly adapting to the growing number of Green OA self-archiving mandates now being adopted by universities, research institutions and research funders worldwide. Some of the conditions they impose are reasonable (such as endorsing the self-archiving of the author's refereed final draft but not the publisher's proprietary PDF, or endorsing institutional repository deposit but not institution-external, 3rd-party repository deposit) and pose no problem for authors, their institutions or their funders. Some conditions are less reasonable (such as 6-12-month embargoes on making access to the deposit Open Access), but these can be adapted to by authors, institutions and funders for the time being, with the help of the  Institutional Repositories' "email eprint request" Button. Some of the conditions, however, are technically arbitrary or even incoherent (such as the distinction between the author's institutional website and the author's institutional repository, or conditions based on metadata or metadata harvestability, rather than the full-text). Technically arbitrary or incoherent conditions should accordingly be ignored by authors, institutions and funders. They are merely leftovers of paper-based thinking that simply do not make sense in the digital medium.

Institutional Repositories' "email eprint request" Button. Some of the conditions, however, are technically arbitrary or even incoherent (such as the distinction between the author's institutional website and the author's institutional repository, or conditions based on metadata or metadata harvestability, rather than the full-text). Technically arbitrary or incoherent conditions should accordingly be ignored by authors, institutions and funders. They are merely leftovers of paper-based thinking that simply do not make sense in the digital medium.

[Excerpted from JISC-REPOSITORIES]

[Excerpted from JISC-REPOSITORIES]

Stevan Harnad:

Here's my tuppence worth on this one -- and it's never failed me (or anyone who has applied it, since the late 1980's. when the possibilities first presented themselves) as a practical guide for action: (A shorter version of this heuristic would be "If the physicists had been foolish enough to worry about it in 1991, or the computer scientists still earlier, would we have the half-million papers in Arxiv or three-quarter million in Citeseerx that we have, unchallenged, in 2009?"):

When a publisher starts to make distinctions that are more minute and arbitrary than can even be made sense of technologically, and are unenforceable, ignore them:

The distinction between making or not-making something freely available on the Web is coherent (if often wrong-headed).

The distinction between making something freely available on the web here but not there is beginning to sound silly (since if it's free on the web, it's effectively free everywhere), but we swallow it, if the "there" is a 3rd-party rival free-riding publisher, whereas the "here" is the website of the author's own institution. Avec les dieux il y a des accommodements: Just deposit in your IR and port metadata to CRs.

But when it comes to DEPOT -- which is an interim "holding space" provided (for free) to each author's institution, to hold deposits remotely until the institution creates its own IR, at which time they are ported home and removed from DEPOT -- it is now bordering on abject absurdity to try to construe DEPOT as a "3rd-party rival free-riding publisher".

We are, dear colleagues, in the grip of an orgy of pseudo-juridical and decidedly supererogatory hair-splitting on which nothing whatsoever hinges but the time, effort and brainware we perversely persist in dissipating on it.

This sort of futile obsessiveness is -- in my amateur's guess only -- perhaps the consequence of two contributing factors:

Bref: Yes, this is "one of those questions one shouldn't really ask"!

Yours curmudgeonly,

Your importunate Archivangelist

Stevan Harnad:

Even incoherently? I think Talat underestimates the supra-legal power of the Law of the Excluded Middle.

Example:

There's no accounting for feelings.

Be sensible (as the half-million physicists and three-quarter million computer scientists have been, for two decades now): Take the "risk."

Stevan Harnad:

Let me make my position clear.

Comments that I make have no legal authority.

Nor am I addressing 3rd parties.

(I am addressing only the authors of refereed journal articles.)

And all I am advising is that they not take leave of their common sense in favor of far-fetched flights of formal fancy -- especially incoherent ones.

Amen.

Johannes

American Scientist Open Access Forum

[Excerpted from JISC-REPOSITORIES]

[Excerpted from JISC-REPOSITORIES]

Les Carr:

[O]ne step away (literally) from the [Wiley-Blackwell] "Best Practice document" is the [Wiley-Blackwell] "Copyright FAQ" in which they elaborate that although the ELF [Exclusive Licence Form] is used for societies, the wholly owned journals still retain the practice of Copyright Assignment. The sample Copyright Assignment document (for the aptly chosen International Headache Society) contains the following text:Such preprints may be posted as electronic files on the author's own website for personal or professional use, or on the author's internal university, college or corporate networks/intranet, or secure external website at the author's institution, but not for commercial sale or for any systematic external distribution by a third party (e.g. a listserve or database connected to a public access server).I think that an institutional repository is OK by that definition. After all, it is a secure external website at the author's institution which is not offering the item for sale nor run by a third party.

Ian Stuart:

Where does this leave the Subject Repository (e.g., arXiv)?

It's not the authors own website, or an intranet at the authors local institution, or an external server at the authors institution... yet it also doesn't offer commercial sales or systematic [my emphasis] distribution to a third party

Where does this leave the Depot?

It's /effectively/ an Institutional Repository, but like arXiv it's not at the authors institution.

.... or is this one of those questions one shouldn't really ask?

Stevan Harnad:

Here's my tuppence worth on this one -- and it's never failed me (or anyone who has applied it, since the late 1980's. when the possibilities first presented themselves) as a practical guide for action: (A shorter version of this heuristic would be "If the physicists had been foolish enough to worry about it in 1991, or the computer scientists still earlier, would we have the half-million papers in Arxiv or three-quarter million in Citeseerx that we have, unchallenged, in 2009?"):

When a publisher starts to make distinctions that are more minute and arbitrary than can even be made sense of technologically, and are unenforceable, ignore them:

The distinction between making or not-making something freely available on the Web is coherent (if often wrong-headed).

The distinction between making something freely available on the web here but not there is beginning to sound silly (since if it's free on the web, it's effectively free everywhere), but we swallow it, if the "there" is a 3rd-party rival free-riding publisher, whereas the "here" is the website of the author's own institution. Avec les dieux il y a des accommodements: Just deposit in your IR and port metadata to CRs.

But when it comes to DEPOT -- which is an interim "holding space" provided (for free) to each author's institution, to hold deposits remotely until the institution creates its own IR, at which time they are ported home and removed from DEPOT -- it is now bordering on abject absurdity to try to construe DEPOT as a "3rd-party rival free-riding publisher".

We are, dear colleagues, in the grip of an orgy of pseudo-juridical and decidedly supererogatory hair-splitting on which nothing whatsoever hinges but the time, effort and brainware we perversely persist in dissipating on it.

This sort of futile obsessiveness is -- in my amateur's guess only -- perhaps the consequence of two contributing factors:

(1) The agonizingly (and equally absurdly) long time during which the research community persists in its inertial state of Zeno's Paralysis about self-archiving (a paralysis of which this very obsession with trivial and ineffectual formal contingencies is itself one of the symptoms and causes). It has driven many of us bonkers, in many ways, and this formalistic obsessive-compulsive tendency is simply one of the ways. (In me, it has simply fostered an increasingly curmudgeonly impatience.) The cure, of course, is deposit mandates.and

(2) The substantial change in mind-set that is apparently required in order to realize that OA is not the sort of thing governed by the usual concerns of either library cataloguing/indexing or library rights-management: It's something profoundly different because of the very nature of OA.Rest your souls. Universal OA is a foregone conclusion. It is optimal, and it is inevitable. The fact that it is also proving to be so excruciatingly -- and needlessly -- slow in coming is something we should work to remedy, rather than simply becoming complicit in and compounding it, by giving ourselves still more formalistic trivia with which to while away the time we are losing until the obvious happens at long last.

Bref: Yes, this is "one of those questions one shouldn't really ask"!

Yours curmudgeonly,

Your importunate Archivangelist

Talat Chaudhri:

...Clearly the copyright system is incoherent and difficult, but nonetheless these publishers have indisputable copyright and may licence it as they please, even incoherently...

Stevan Harnad:

Even incoherently? I think Talat underestimates the supra-legal power of the Law of the Excluded Middle.

Example:

"You may deposit this article on the web if you have a blue-eyed maternal uncle AND you may not deposit this article on the web if you have a blue-eyed maternal uncle."Unverifiable, unenforcable, and incoherent. But Talat feels it would be "frankly inappropriate to tell others to break the law at their own risk" by ignoring something like this.

There's no accounting for feelings.

Be sensible (as the half-million physicists and three-quarter million computer scientists have been, for two decades now): Take the "risk."

Charles Oppenheim:

Let me make my position clear. Comments that I make have no legal authority. I take no responsibility for any actions a reader might take (or not take) as a result of reading my opinion, and that in any cases of doubt, readers should take formal legal advice. Anyone who advises third parties to do something that is potentially infringing without such a health warning could find themselves accused by rights owners of authorising infringement, which means they would be just as liable to pay damages as the person who took the advice.

I agree with Talat that 100% OA is not necessarily inevitable, despite my hope that it does come to pass. Just because something is technically possible and makes economic sense does not mean it is bound to occur.

Stevan Harnad:

Let me make my position clear.

Comments that I make have no legal authority.

Nor am I addressing 3rd parties.

(I am addressing only the authors of refereed journal articles.)

And all I am advising is that they not take leave of their common sense in favor of far-fetched flights of formal fancy -- especially incoherent ones.

Amen.

Johannes

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Sunday, December 23. 2007

From Father Christmas to all the little boys and girls wishing for Open Access

On Sun, 23 Dec 2007, [anonymous] wrote:

On Sun, 23 Dec 2007, [anonymous] wrote:Dear Father Christmas,

My wish goes towards allowing any researcher free access to current scientific information -- and when I say free, I mean without any constraint of fees, subscription, copyright. And what would be better than having open archives/repositories?

But I know this is pure utopia.

Even you, Father Xmas, are you on Open Access?

Since you are a creation of human intellect, someone must have an exclusive copyright on you, so is it even allowed to quote you without permission?

How to get out of this dilemma? Recently, in France and Germany, lawmakers wrote a new law, punishing anybody intending to infringe copyright with enormous fines...

My fellow European scientists are afraid and no longer dare to express their ideas. Father Xmas, give us some suggestions to be discussed in our Forum, but do not tell anybody else: we don't want to be prosecuted...

REPLY FROM FATHER XMAS, NORTH POLE:

Dear little boys and girls everywhere who yearn for Open Access:

Yes, there is a way that you can have the Open Access you say you so fervently desire. But Father Christmas cannot give it to you, any more than Father Christmas can give you big muscles, if that is what you yearn for. All Father Christmas can do is tell you how you yourselves can build the big muscles you desire (by exercising daily with increasing weights). And for Open Access it is exactly the same: It depends entirely on you, dear children, each and every one of you.

Nor can you build big muscles from one day to the other. If you try to lift too heavy a weight, too early, you only cause yourself muscle strain. So don't insist on too much overnight. Start with one simple fact that is easy to assimilate:

Your institution has no Institutional Repository yet? Then, for the time being, deposit your postprints in a central repository, like CogPrints or Depot or Arxiv or HAL or PubMed Central. But do the deposit now.

The journal in which it is published does not yet endorse immediate OA self-archiving? Then, for the time being, set access to the deposit as Closed Access rather than Open Access for as long as the journal embargoes access. But do the deposit now. That's all. If all the little boys and girls did that before Christmas this year, on Christmas day all the current research worldwide would be visible worldwide, 62% of it already Open Access (because 62% of journals already endorse immediate OA self-archiving).

For the remaining 38% deposited in Closed Access, the metadata (author, title, journalname, date etc.) would be immediately visible worldwide, so any user who wanted to access the full-text could immediately email the author to request an eprint by email. That is not immediate 100% OA, but it is almost-immediate, almost-OA. Many Repositories already have a button whereby eprints can be requested and emailed semi-automatically: one keystroke from the requester, one keystroke from the author.

If all of you deposited all your current postprints before Christmas, boys and girls, all Repositories would soon have that button. And the growth of the OA muscles in this way, worldwide, keystroke by keystroke, would soon hasten the natural and well-deserved death of the remaining publisher-embargoes. (Yes, dear children, it is within the spirit of Christmas to speak about the "death" of evil things, such as plagues, hunger, war, injustice, and research access embargoes!)

So, dear little boys and girls, there are some things for which wishing or writing a letter to Santa Claus is not quite enough. Time to start exercising your little fingers. And if you find doing the keystrokes for depositing all your current articles before Christmas too low an ergonomic priority as long as it remains voluntary -- first, congratulations for having published so much at such a young age!

And second, instead of just writing to St. Nick, I suggest writing to the Principal, Rector, Vice-Chancellor or Provost of your school, to make known to them your fervent desire for OA, pointing out also your faintness of will about doing the keystrokes voluntarily as long as you feel you would be doing those dactylographics alone. Father Christmas's elves understand that as little researchers, you are already so busy and overloaded that you cannot steal the time to exercise your fingers in this way while your school gives you so much other homework to do if your other school-mates are not required to do it too.

So if you all write to your Principal asking that the school itself should make this digital muscle-building part of its standard athletic curriculum for all its pupils -- making the keystrokes mandatory for all of you -- then that mandate will ensure OA self-archiving its proper place in your hierarchy of priorities. The rewards will be felt in your year-end marks (if you don't mind Father Christmas talking about such unpleasant matters at a time we should be thinking of toys rather than toil!), because self-archiving builds the citations as surely as it builds muscles.

So don't worry about reforming copyright law. Copyright law is just the Cheshire Cat's grin, suspended in thin air, without you. It will reform itself in due course, if you just do what is already in your own hands (and always has been, ever since the dawn of the online era), right now, on the night before Xmas 2008.

Carr, L. and Harnad, S. (2005) Keystroke Economy: A Study of the Time and Effort Involved in Self-Archiving.Your faithful old

"Optimizing OA Self-Archiving Mandates: What? Where? When? Why? How?"

Kris Kringle

Sunday, November 18. 2007

Open Access in the Last Millennium

I thought that as the American Scientist Open Access Forum approaches its 10th year, readers might find it amusing (and perhaps enlightening) to see where the discourse stood 20 years ago. That was before the Web, before online journals, and before Open Access -- yet many of the same issues were already being debated.

I thought that as the American Scientist Open Access Forum approaches its 10th year, readers might find it amusing (and perhaps enlightening) to see where the discourse stood 20 years ago. That was before the Web, before online journals, and before Open Access -- yet many of the same issues were already being debated.Alhough I might have traced it back still further, to BBS Open Peer Commentary, 30 years ago, and although my first substantive posting was September 27 1986, for me it feels as if it all began with a jolt on November 19 1986, on sci.lang, with "Saumya,...you have shit-for-brains" -- which led to "Skywriting" (c. 1987, unpublished, unposted), which turned into "Scholarly Skywriting" (1990), Psycoloquy (1991), "PostGutenberg Galaxy" (1991), CogPrints (1997), the Self-Archiving FAQ (as of 1997), the AmSci Forum (1998), the critique of the e-biomed proposal (1999), EPrints (2000), mandates and metrics (2001), and then the BOAI (2002).

See how much of it is already lurking in this 1990 posting on COMMED:

Date: Tues, Mar 13 1990 4:12 am

From: har...@Princeton.EDU (Stevan Harnad)

To: loeb@geocub

Subject: Re: Journals

Cc: PA...@phoenix.cambridge.ac.uk, jour_...@nyuacf.BITNET

ON THE SCHOLARLY AND EDUCATIONAL POTENTIAL OF MULTIPLE EMAIL NETWORKS

[From: COMMED]Stevan Harnad

Princeton University

Gerald M. Phillips, Professor, Speech Communication, Pennsylvania State

University (G...@PSUVM.BITNET) wrote on Commed against the idea of

"on-line journals." His critique contains enough of the oft-repeated

(and I think erroneous) criticisms of the new medium that I think it's

worth a point by point rebuttal. I write as the editor, for over a

decade now, of a refereed international journal published by Cambridge

University Press (in the conventional paper/print medium), but also as

an impassioned advocate of multiple-email networks and their (I think)

revolutionary potential. I am also the new moderator of PSYCOLOQUY,

an email list devoted to scholarly electronic discussion in psychology

and related disciplines. Professor Phillips wrote:

> There is [1] an explicit hostility to print media on computer networks.

> There is a crisis in the publishing industry because of [2] technological

> innovations, [3] TV, and second hand booksellers, and among book reviewers

> there is consternation because [4] the number of journals proliferates and

> the quality of the texts declines. I am responding to the proposal to

> establish an electronic journal, and I am responding negatively.

Not one of these points speaks against electronic journals; rather,

they are points in their favor: (1) The hostility to print is justified,

inasmuch as it wastes time and resources and confers no advantage (which

cannot be duplicated by resorting to hard copy when needed anyway).

(2) Technological innovations such as photo-copying are problems for

the print media -- unsolved and probably unsolvable -- but not for the

virtual media, whose economics will be established pre-emptively along

more realistic lines, given the new technology. The passive CRTs in (3)

TV may be competing with the written word, but the interactive CRTs in

the electronic media are in a position to fight back. (4) Word glut and

quality decline are problems with the message (and how we control its

quality -- a real problem, in which I am very interested), not with the

medium. This leaves nothing of this first list of objections. Let's go on:

> The book, magazine, or journal is still the most convenient learning

> center known to civilization. It is portable, requires no power supply, is

> easily stored, and one can write comments on the pages without resorting

> to hypertext.

These arguments would have been just as apt if applied to Gutenberg

on behalf of the illuminated manuscript, or against writing itself, in

favor of the oral tradition. Other than habit, they have no logical or

practical support at all. And the clincher is that the situation is not

"either/or." To the extent that people are addicted to their marginal

doodling (or to electricity-free yurts), hard copy will always be

available as a supplement.

> Furthermore, the contemplation that enters composition of the

> typical article is important. Hasty publication results in error and sometimes

> danger. I urge examination of the editorial policies of NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL

> OF MEDICINE or DAEDALUS as examples of the best editorial policies. It is

> crucial in publishing to have careful editing and responsible writing.

There is one logical error and one non sequitur here: (i) Making it

POSSIBLE for people to communicate faster and on a more global scale

does not imply that they are no longer allowed to wait and reflect as

long as they wish! (ii) Ceterum censeo: Quality control is a

medium-independent problem; I have plenty of ideas about how to

implement peer review in this medium even more effectively than in the

print media.

> I do not wish to indict users of electronic media, but I have encountered

> a fair share of irresponsible people who write out of passion or worse --

> cuteness.

The problem here is a demographic one, having to do with the anarchic

initial conditions in which the new medium was developed. "Flaming"

was what the first electronic discussion was called, and it began as

spontaneous combustion among the creators of the medium (computer hackers,

for the most part) and students (who have a lot of idle time on their

hands). The form of trivial pursuit that ensued is no more representative

of the intrinsic possibilities of this medium than it would have been

if we had left it up to Gutenberg and a legion of linotype operators

to decide for us all what should appear on the printed page. Again, the

problem is with implementation and quality control, not the medium itself.

> I realize how important some exchanges are and I will argue

> with data and without passion for the efficacy of applying CMC to some

> aspects of classroom operation. Computerized cardfiles and other databases

> are essential to good scholarship. Networks like AMANET and similar

> medical operations provide important information conveniently. What

> characterizes a totally responsible network, however, is the willingness

> to spend money to make it work. Accumulating a database and monitoring its

> contents is crucial for uses of a network must have confidence in what they read.

These applications are all commendable, but supremely unimaginative.

The real revolutionary potential of electronic network communication is

in scholarship rather than education. I am convinced that the medium

is better matched to the pace and scope and interactiveness of human

mentation than any of its predecessors. In fact, it is as much of a

milestone as the advent of writing, and finally returns the potential pace

of the interaction -- which writing and print slowed down radically --

to the tempo of the natural speech from which so much of our cognitive

capacity arose.

> A great many scholars (mostly untenured) rail at the policies of contempo-

> rary scholarly journals, and often they are "on target." Journals sometimes

> use an "old boy" network to exclude new and vital ideas. Journals are often

> ponderously slow and it is difficult for many people to take editorial

> criticism. On the other hand, journals protect us from egregious error and

> and libel and the copyright laws protect us from plagiarism.

But the egregious error here is to fail to realize that electronic

networks can exercise peer review just as rigorously (or unrigorously)

as any other medium. And just as there are hierarchies of print

journals (ranked with respect to how rigorously they are refereed),

this can be done here too, including levels at which manuscripts or

ideas are circulated to one's peers for pre-referee scrutiny, as in

symposia and conferences, or even informal discussion. The possibilities

are enormous; objections like the above ones (and they are not unique

to Professor Phillips) serve only to demonstrate how the entrenched old

medium and its habits can blind us to promising alternatives.

> Plagiarism is a major concern in using an electronic network. I am

> hesitant to share material that might be useful because my copyrights are

> not protected on this network. I enjoy the chitchat effect, but I have

> told several people who have contacted me about my "on-line" course, that

> I would be happy to share articles or have them come out an observe. I

> would not attempt to offer advice using this medium. It would be

> guaranteed to be half-baked and inapposite.

I have two replies here; one objective and quite decisive, the other

a somewhat subjective observation: There are ways to implement peer

discussion that will preserve priority as safely as the ordinary

mail, telephone and word-processor media (none completely immune to

techno-vandalism these days, by the way) to which we already entrust

our prepublication ideas and findings. I'll discuss these in the future.

As food for thought, consider that it would be simple to implement a

network with read/write access only for a group of peers in a given

specialty, where every posting is seen by everyone who matters in the

specialty (and is archived for the record, to boot). These are the people

who ASSIGN the priorities. A wider circle might have read-only access,

and perhaps one of them might try (and even succeed) to purloin an

idea and publish it as his own -- either in a low-level print journal

or a low-level electronic group. So what? The peers saw it first, and

know whence it came, and where and when, with the archive to confirm it

(printed out in hard copy, if you insist!). That's the INTRINSIC purpose

of scholarly priority. If some enterprising vita-stuffer up for promotion

at New Age College pries the covers off my book and substitutes his own,

that's not a strike against the printed medium, is it?

Now the subjective point: It seems paradoxical, to say the least, to be

worried about word glut and quality decline at the same time as being

preoccupied with priority and plagiarism. Here is some more food for

thought: The few big ideas that there are will not fail to be attributed

to their true source as a result of the net. As to the many little ones

(the "minimal publishable units," or what have you), well, I suppose

that a scholar can spend his time trying to protect those too -- or he

can be less niggardly with them in the hope that something bigger might

be spawned by the interaction.

It's all a matter of scale. I'm inclined to think that for the really

creative thinker, ideas are not in short supply. It's the tree that

bears the fruit that matters: "He who steals my apples, steals trash,"

or something like that. The rival anecdote is that Einstein was asked

in the fifties by some tiresome journalist -- a harbinger of our

self-help/new-age era -- what activity he was usually engaged in when

he got his creative ideas (shaving? showering? walking? sleeping?), and

he replied that he really couldn't say, because he had only had one or

two creative ideas in his entire lifetime... (Nor was he particularly

secretive about them, I might add, engaging in intense scholarly

correspondence about them with his peers, most of whom could not even

grasp, much less pass them off as their own.)

> While serving on a promotion and tenure committee, I opposed consideration

> of materials "published" on-line in examining the credentials of candidates.

> That is an antediluvian view, I know, but in the sciences especially,

> accuracy and responsibility is critical and to date, only the referee

> process give us any assurance at all.

Too bad. Promotion/tenure review is a form of peer review too, and is

not such an oracular machine as to afford to ignore potentially

informative data. I, for one, might even consider looking at

unpublished (hence, a fortiori, unrefereed) manuscripts if there

appeared to be grounds for doing so, in order to make a more informed

decision. But never mind; if the direction I am advocating prevails,

peer review, such as it is, will soon be alive and well on the

electronic networks, and contributions will be certifiably CV-worthy.

> Interchanges like this are useful. We get a chance to exchange views with

> people we do not know and often we find some intriguing possibilities in

> these notes and messages. But I still do not know who I am communicating

> with and I have no confirmation of their data. I can use caveat emptor on

> their ideas, but I cannot give them professional credit for them, nor can

> I claim any for my own.In short, here is your extreme argument AGAINST

> electronic journals.

There is, I am told, a complexity-theoretic bottom-line in networking

called the "authentication problem." I can in principle post a libelous,

plagiaristic message in your name without being detected; hence it will be

difficult to formulate enforceable laws to regulate the net. In practice,

this need not be a problem, however, so look on the bright side. I

really am the one indicated on my login. And even if I weren't, it hardly

matters for THIS discussion (as opposed to the future peer-reviewed ones

mentioned earlier). All that matters is my message, which can stand on

its own merits as a counterargument FOR electronic journals.

Stevan Harnad

Gerald M. Phillips

> Two points you did not attack were (1) the problem of protection of

> copyrights and (2) the convenience of books. Note, please that read

> only does not protect anyone so long as personal computers have print

> screen keys.

Currently, copyright is protected if you copyright a hard copy of what

you have written. Anyone is free to do this prior to every screenful,

but it sure would slow "skywriting" down to the old terrestrial pace.

In practice, however, we don't bother to copyright until we're much

further downstream: Our scholarly correspondence, our conference papers

and our preliminary drafts circulated for "comment without quotation"

do not enjoy copyright, so why be more protective of electronic

drafts? Because they're easier to abscond with? But, as I wrote earlier,

if the primary read/write network to which it is posted consists of

all the peers of the realm, and they see it first, and it's archived

when they see it, what is there to fear? What better way to establish

priority? Isn't it their eyes that matter?

Books are much more a habit than a convenience. I'm sure that if you

gave me an itemized list of their virtues I could match them (and then

some) with the merits of electronic text. (E.g., books are portable,

but they have to be physically duplicated and lugged; in principle,

everything written could be available everywhere there's a plug or

antenna, to anyone, anytime... etc.)

> Furthermore, the overwhelming number of faculties do not

> participate in networks. It is somewhat like the problem people are

> having with VCRs. Most people can learn how to play movies. Few bother

> to learn how to record from broadcasts. Most PC users really have

> expensive typewriters. I know -- it is their own fault. And it is

> probably different in the sciences, but it seems to me that designing

> access to knowledge for a minority will only widen the ignorance gap.

Computers and networks have become so friendly that everyone is just a

2-minute demo away from sufficient facility for full access. The barrier

is so tiny that it's absurd to think that it can hold people back,

particularly once the revolutionary potential of scholarly skywriting is

demonstrated and a quorum of the peers of each realm become addicted. The

"virtual" environment can mimic what we're used to as closely as necessary

to mediate a total transition. In fact, nothing has a better chance

to NARROW the ignorance gap than the global, interactive and virtually

instantaneous airwaves of the friendly skies.

> I'd be interested in your proposals about ensuring quality. I am not so sure

> of your proposals re: read only, but I'd be happy to look at them. I am not

> a Luddite. I believe I have the largest enrollment class learning entirely

> via computer-mediated communication. And it is a performance class (group

> problem solving). It is both popular and effective, but the computer has

> been adapted to the needs of the class not the reverse. I think that

> putting journals on-line (at least at the moment) is a case of "we have the

> machinery, why not use it?"

The idea is to have a vertical (peer expertise) and a horizontal

(temporal-archival) dimension of quality control. The vertical dimension

would be a hierarchy of expertise, with read/write access for an

accredited group of peers at a given level and read-only access at the

level immediately below it, but with the right to post to a peer at

the next higher level, who can in turn post your contribution for you,

if he judges that it to is good enough. (A record of valuable mediated

postings could result in being voted up a level.) A single editor, or an

editorial board, are simply a special case of this very same mechanism,

where one person or only a few mediate all writing privileges.

That's the vertical hierarchy, based on degrees of expertise,

specialization, and record of contributions in a given field. In

principle, this hierarchy can trickle down all the way to general access

for nonspecialists and students at the lowest read/write level (the

equivalent of "flaming," and, unfortunately, the only level that exists

among the "unmoderated" groups on the net currently, while in today's

so-called "moderated" groups all contributions are filtered through one

person, usually one with no special qualifications or answerability).

So far, even among the elite, this would still be just brainstorming,

at the pilot stage of inquiry. The horizontal dimension would then take

the surviving products of all this skywriting, referee them the usual

way (by having them read, criticized and revised under peer scrutiny)

and then archiving them (electronically) according to the level of rigor

of the refereeing system they have gone through (corresponding, more or

less, to the current "prestige hierarchy" and level of specialization

among print journals). Again, an unrefereed "vanity press" could be the

bottom of the horizontal hierarchy.

> And please address the issue of those of us who make our living out of the

> printed word and fear plagiarism above earthquakes and forest fires.

> Gerald M. Phillips, Pennsylvania State University

I imagine that a different system of values and expectations will be

engendered by the net. One may have to make one's reputation increasingly

by being a fertile collaborator rather than a prolific monad. I think

interactive productivity ("interproductivity") will turn out to be

just as viable, answerable and rewardable a way of establishing one's

intellectual territory as the old way; it's just that the territory will

be much less exclusive, more overlapping and interdependent. That's the

cumulative direction in which inquiry has been heading all along anyway.

As to words themselves: I think it will be possible to protect them

just as well as in the old media. The ones who are really able to use

the language (like the ones who have really new ideas or findings) will

still be a tiny minority, as they are now and always will be, and we'll

know even better who they are and what they have written. It'll be easier

to steal a few of their screenfuls for lowly use, but, as always, it will

be impossible to steal their source. As to the rest -- marginal ideas and

marginal prose -- I can't really work up a sense of urgency about them;

it seems to me, however, that it will be just as easy as before to make

sure they get their dubious due, in terms of their official standing in

the two-dimensional hierarchy.

Stevan Harnad

Harnad, S. (1990) Scholarly Skywriting and the Prepublication Continuum of Scientific Inquiry Psychological Science 1: 342 - 343 (reprinted in Current Contents 45: 9-13, November 11 1991).Stevan Harnad

Harnad, S. (1991) Post-Gutenberg Galaxy: The Fourth Revolution in the Means of Production of Knowledge. Public-Access Computer Systems Review 2 (1): 39 - 53 (also reprinted in PACS Annual Review Volume 2 1992; and in R. D. Mason (ed.) Computer Conferencing: The Last Word. Beach Holme Publishers, 1992; and in: M. Strangelove & D. Kovacs: Directory of Electronic Journals, Newsletters, and Academic Discussion Lists (A. Okerson, ed), 2nd edition. Washington, DC, Association of Research Libraries, Office of Scientific & Academic Publishing, 1992); and in Hungarian translation in REPLIKA 1994; and in Japanese in Research and Development of Scholarly Information Dissemination Systems 1994-1995.

Harnad, S. (1995) Universal FTP Archives for Esoteric Science and Scholarship: A Subversive Proposal. In: Ann Okerson & James O'Donnell (Eds.) Scholarly Journals at the Crossroads; A Subversive Proposal for Electronic Publishing. Washington, DC., Association of Research Libraries, June 1995.

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Tuesday, September 18. 2007

On Janet Malcolm on Shipley & Schwalbe on Email in the New York Review: The Power of Skywriting

On: Janet Malcolm "Pandora's Click," a review of Shipley & Schwalbe's The Essential Guide to Email for Office and Home by David Shipley and Will Schwalbe

The Power of Skywriting

What makes email into a potential nuclear weapon (and, like nuclear energy, amenable to both melioration and mischief) is its "skywriting" potential: the fact that multiple copies can easily, and almost instantly, proliferate, intentionally or unintentionally, to targets, intended and unintended, all over the planet. Paper letter-writing (indeed all writing) already had much the same capability for hastiness, thoughtlessness, solecism and misinterpretation, and it too was deprived of the emotional, interpersonal cues native to the oral tradition of real-time, "live," interactive speech. But it was when writing soared skyward into cyberspace with email and the web that it came into its own. Hearsay, even when augmented by video and telecommunications, never quite attained the destructive (and constructive) power of skywriting. It's all a matter of timing, scope and scale. Verba volunt, scripta manent. Harnad, S. (2003) Back to the Oral Tradition Through Skywriting at the Speed of Thought. Interdisciplines. In: Salaün, Jean-Michel & Vendendorpe, Christian (eds.). Le défi de la publication sur le web: hyperlectures, cybertextes et méta-éditions. Presses de l'enssib.

What makes email into a potential nuclear weapon (and, like nuclear energy, amenable to both melioration and mischief) is its "skywriting" potential: the fact that multiple copies can easily, and almost instantly, proliferate, intentionally or unintentionally, to targets, intended and unintended, all over the planet. Paper letter-writing (indeed all writing) already had much the same capability for hastiness, thoughtlessness, solecism and misinterpretation, and it too was deprived of the emotional, interpersonal cues native to the oral tradition of real-time, "live," interactive speech. But it was when writing soared skyward into cyberspace with email and the web that it came into its own. Hearsay, even when augmented by video and telecommunications, never quite attained the destructive (and constructive) power of skywriting. It's all a matter of timing, scope and scale. Verba volunt, scripta manent. Harnad, S. (2003) Back to the Oral Tradition Through Skywriting at the Speed of Thought. Interdisciplines. In: Salaün, Jean-Michel & Vendendorpe, Christian (eds.). Le défi de la publication sur le web: hyperlectures, cybertextes et méta-éditions. Presses de l'enssib.

The Power of Skywriting

What makes email into a potential nuclear weapon (and, like nuclear energy, amenable to both melioration and mischief) is its "skywriting" potential: the fact that multiple copies can easily, and almost instantly, proliferate, intentionally or unintentionally, to targets, intended and unintended, all over the planet. Paper letter-writing (indeed all writing) already had much the same capability for hastiness, thoughtlessness, solecism and misinterpretation, and it too was deprived of the emotional, interpersonal cues native to the oral tradition of real-time, "live," interactive speech. But it was when writing soared skyward into cyberspace with email and the web that it came into its own. Hearsay, even when augmented by video and telecommunications, never quite attained the destructive (and constructive) power of skywriting. It's all a matter of timing, scope and scale. Verba volunt, scripta manent. Harnad, S. (2003) Back to the Oral Tradition Through Skywriting at the Speed of Thought. Interdisciplines. In: Salaün, Jean-Michel & Vendendorpe, Christian (eds.). Le défi de la publication sur le web: hyperlectures, cybertextes et méta-éditions. Presses de l'enssib.

What makes email into a potential nuclear weapon (and, like nuclear energy, amenable to both melioration and mischief) is its "skywriting" potential: the fact that multiple copies can easily, and almost instantly, proliferate, intentionally or unintentionally, to targets, intended and unintended, all over the planet. Paper letter-writing (indeed all writing) already had much the same capability for hastiness, thoughtlessness, solecism and misinterpretation, and it too was deprived of the emotional, interpersonal cues native to the oral tradition of real-time, "live," interactive speech. But it was when writing soared skyward into cyberspace with email and the web that it came into its own. Hearsay, even when augmented by video and telecommunications, never quite attained the destructive (and constructive) power of skywriting. It's all a matter of timing, scope and scale. Verba volunt, scripta manent. Harnad, S. (2003) Back to the Oral Tradition Through Skywriting at the Speed of Thought. Interdisciplines. In: Salaün, Jean-Michel & Vendendorpe, Christian (eds.). Le défi de la publication sur le web: hyperlectures, cybertextes et méta-éditions. Presses de l'enssib.Friday, August 10. 2007

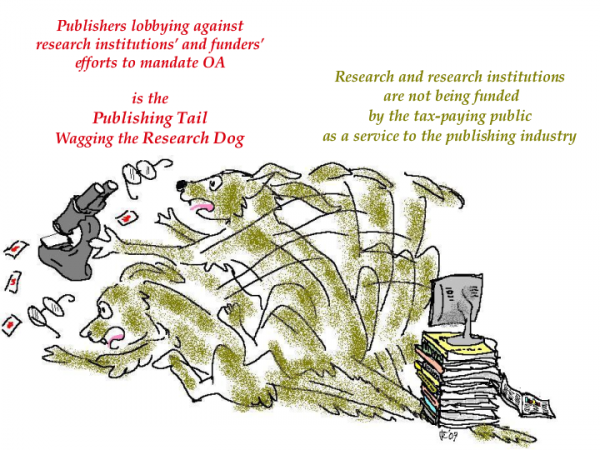

The Publishing Tail Wagging the Research Dog

To fast-forward to 2012 see

"Research Works Act H.R.3699:

"Research Works Act H.R.3699:The Private Publishing Tail

Trying To Wag The Public Research Dog,

Yet Again"

Publisher anti-OA Lobby Triumphs in European Commission (2007)

Drawn by

Judith Economos

(feel free to use to promote OA and to bait "pit-bulls")

Monday, December 25. 2006

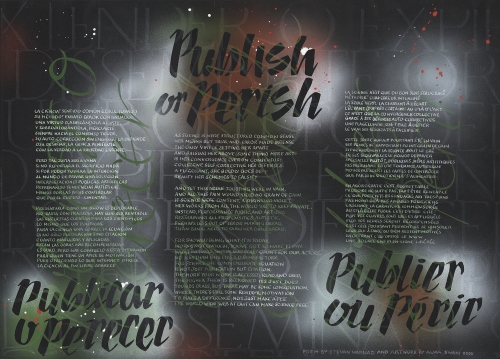

2007: Depositar y Prosperar

Executed in gouache on black Canson Mi-Teintes pastel paper using William Mitchell metal nibs, brushes and airbrush.

See: Full Size Original 600 x 420 mm.

Text: Stevan Harnad

Tuesday, December 12. 2006

Raincoat Science

These cartoons by Judith Economos don't really capture the "raincoat" metaphor. (What they are actually illustrating is "The Geeks and the Irrational.")

The raincoat metaphor (to ruin it, by explaining it) speaks for itself: Rain is obvious. The (cumulative) disadvantages of wetness are obvious. That raincoats are for shielding you from the rain is obvious. That raincoats can shield you from the rain is obvious. Yet, Zeno-like, the raincoat-advice -- "It's raining: Time to put on the ol' raincoats!" -- is not taken, for at least 34 silly, obviously defeasible reasons: "It's not raining. You can't stop the rain. Rain's good for you. God meant us to get wet. Raincoats are illegal. Raincoats don't work. Raincoats don't last. Raincoats will ruin the health-care industry. We need to block the clouds directly instead. Putting on a raincoat takes too long. Putting on a raincoat is too much work. I can't button my raincoat..." (See "Raincoat Science: 43 More Open Access Haikus")

But Judith's cartoons are just too good not to show, even though they are about the green vs gold option rather than the don (sic) vs. don't option...

(Judith Economos also illustrated these Open Access rhymes. Feel free to use any of this to promote OA.)

The raincoat metaphor (to ruin it, by explaining it) speaks for itself: Rain is obvious. The (cumulative) disadvantages of wetness are obvious. That raincoats are for shielding you from the rain is obvious. That raincoats can shield you from the rain is obvious. Yet, Zeno-like, the raincoat-advice -- "It's raining: Time to put on the ol' raincoats!" -- is not taken, for at least 34 silly, obviously defeasible reasons: "It's not raining. You can't stop the rain. Rain's good for you. God meant us to get wet. Raincoats are illegal. Raincoats don't work. Raincoats don't last. Raincoats will ruin the health-care industry. We need to block the clouds directly instead. Putting on a raincoat takes too long. Putting on a raincoat is too much work. I can't button my raincoat..." (See "Raincoat Science: 43 More Open Access Haikus")

But Judith's cartoons are just too good not to show, even though they are about the green vs gold option rather than the don (sic) vs. don't option...

(Judith Economos also illustrated these Open Access rhymes. Feel free to use any of this to promote OA.)

« previous page

(Page 2 of 2, totaling 17 entries)

EnablingOpenScholarship (EOS)

Quicksearch

Syndicate This Blog

Materials You Are Invited To Use To Promote OA Self-Archiving:

Videos:

audio WOS

Wizards of OA -

audio U Indiana

Scientometrics -

The American Scientist Open Access Forum has been chronicling and often directing the course of progress in providing Open Access to Universities' Peer-Reviewed Research Articles since its inception in the US in 1998 by the American Scientist, published by the Sigma Xi Society.

The American Scientist Open Access Forum has been chronicling and often directing the course of progress in providing Open Access to Universities' Peer-Reviewed Research Articles since its inception in the US in 1998 by the American Scientist, published by the Sigma Xi Society.

The Forum is largely for policy-makers at universities, research institutions and research funding agencies worldwide who are interested in institutional Open Acess Provision policy. (It is not a general discussion group for serials, pricing or publishing issues: it is specifically focussed on institutional Open Acess policy.)

You can sign on to the Forum here.

Archives

Calendar

|

|

May '21 | |||||

| Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun |

| 1 | 2 | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

| 31 | ||||||

Categories

Blog Administration

Statistics

Last entry: 2018-09-14 13:27

1129 entries written

238 comments have been made