Thursday, September 4. 2008

Offloading Cognition onto Cognitive Technology

Dror, I. and Harnad, S. (2009) Offloading Cognition onto Cognitive Technology. In: Cognition Distributed: How Cognitive Technology Extends Our Minds, John Benjamins. (In Press)

Abstract: "Cognizing" (e.g., thinking, understanding, and knowing) is a mental state. Systems without mental states, such as cognitive technology, can sometimes contribute to human cognition, but that does not make them cognizers. Cognizers can offload some of their cognitive functions onto cognitive technology, thereby extending their performance capacity beyond the limits of their own brain power. Language itself is a form of cognitive technology that allows cognizers to offload some of their cognitive functions onto the brains of other cognizers. Language also extends cognizers' individual and joint performance powers, distributing the load through interactive and collaborative cognition. Reading, writing, print, telecommunications and computing further extend cognizers' capacities. And now the web, with its network of cognizers, digital databases and software agents, all accessible anytime, anywhere, has become our “Cognitive Commons,” in which distributed cognizers and cognitive technology can interoperate globally with a speed, scope and degree of interactivity inconceivable through local individual cognition alone. And as with language, the cognitive tool par excellence, such technological changes are not merely instrumental and quantitative: they can have profound effects on how we think and encode information, on how we communicate with one another, on our mental states, and on our very nature.

Abstract: "Cognizing" (e.g., thinking, understanding, and knowing) is a mental state. Systems without mental states, such as cognitive technology, can sometimes contribute to human cognition, but that does not make them cognizers. Cognizers can offload some of their cognitive functions onto cognitive technology, thereby extending their performance capacity beyond the limits of their own brain power. Language itself is a form of cognitive technology that allows cognizers to offload some of their cognitive functions onto the brains of other cognizers. Language also extends cognizers' individual and joint performance powers, distributing the load through interactive and collaborative cognition. Reading, writing, print, telecommunications and computing further extend cognizers' capacities. And now the web, with its network of cognizers, digital databases and software agents, all accessible anytime, anywhere, has become our “Cognitive Commons,” in which distributed cognizers and cognitive technology can interoperate globally with a speed, scope and degree of interactivity inconceivable through local individual cognition alone. And as with language, the cognitive tool par excellence, such technological changes are not merely instrumental and quantitative: they can have profound effects on how we think and encode information, on how we communicate with one another, on our mental states, and on our very nature.

Wednesday, January 30. 2008

The University's Mandate To Mandate Open Access

This is a guest posting (written at the invitation of Gavin Baker) for the new blog

This is a guest posting (written at the invitation of Gavin Baker) for the new blog "Open Students: Students for Open Access to Research."

Other OA activists are also encouraged to contribute to the Open Students blog.

My guess is that Open Access (OA) already sounds old hat to the current generation of students, and that you are puzzled more about why we are still talking about OA happening in the future, rather than in the distant past (as the 80's and 90's must appear to you!).

SUMMARY: Open Access (OA) will not come until universities, the research-providers, make it part of their mandate not only to publish their research findings, as now, but also to see to it that the few extra keystrokes it takes to make those published findings OA -- by self-archiving them in their institutional repositories, free for all online -- are done too. Students are in a position to help convince their universities to go ahead and mandate OA self-archiving, at long last.

Well, you're right to be both puzzled and impatient, but let me try to explain why it's been taking so long. (I say "try" because I have to admit that I too am still somewhat perplexed by the slowness of OA growth, even after sampling the sluggishness of its pace for nearly 2 decades now!) And then I'll try to suggest what you students can do to help speed OA on its way to its obvious, optimal, and long overdue destination.

What OA Is Not

First, what is Open Access (OA)? It's not about Open Source (OS) software -- i.e., it's not about making computer programs either open or free (though of course OA is in favor of and compatible with OS).

It's not about Creative Commons (CC) Licensing either -- i.e., it is not about making all digital creations re-usable and re-publishable (though again OA is in favor of and compatible with CC licensing).

Nor is it about "freedom of information" or "freedom of digital information" in general. (That's much too broad and vague: OA has a very specific kind of information as its target.)

And, I regret to say, OA is not about helping you get or share free access to commercial audio or video products, whether analog or digital: OA is completely neutral about that. OA's target is only author give-aways, not "consumer sharing" (though of course free user access webwide will be the outcome, for OA's special target content).

What Is OA's Target Content?

So let's start by being very explicit about OA's target content: It is the 2.5 million articles a year that are published in the planet's 25,000 peer-reviewed scholarly and scientific journals.

Eventually OA might also extend to some scientific and scholarly books (the ones that authors want to give away) and also to scholarly scientific data (if and when the researchers that collected them are ready to give them away); it may also extend to some software, some audio and some video.

But the only content to which OA applies without a single exception today is peer-reviewed journal articles. They are the works that their authors always wrote just so they should be read, used, applied, cited and built upon (mostly by their fellow researchers, worldwide). This is called "research impact". They were never written in order to earn their authors income from their sale.

These special authors -- researchers -- never sought or received any revenue from the sale of their journal articles. Indeed, the fact that there was a price-tag attached to accessing their articles (a price-tag usually paid through institutional library subscriptions) meant that these researcher-authors, and research itself, were losing research impact, because subscriptions to these journals were expensive, and most institutions could only afford access to a small fraction of them.

What Is OA?

To try to compensate for these access barriers in the old days of paper, these special give-away authors would provide supplementary access, by mailing free individual reprints of their articles, at their own expense, to any would-be user who had written to request a reprint. You can imagine, though, how slow, expensive and inefficient it must have been to have to supplement access in this way, in light of what the web has since made possible: First, the possibility of emailing eprints was an improvement, but the obvious and optimal solution was to put the eprint on the web directly, so any would-be user, webwide, could instantly access it directly, at any time.

And that, dear students, is the essence of OA: free, immediate, permanent, webwide access to peer-reviewed research journal articles: give-away content -- written purely for usage and impact, not for sales revenue -- finding, at last, the medium in which it can be given away, free for all, globally, big-time.

OA = Gold OA or Green OA

You thought OA was something else? Another form of publishing, maybe? with the author-institution paying to publish the article rather than the user-institution paying to access it? That is OA journal publishing. But OA itself just means: free online access to the article itself.

There are clearly two ways an author can provide free online access to an article: One is by publishing it in an OA journal (this is called the "golden road" to OA, or simply "Gold OA") and the other is by publishing it in a conventional subscription journal, but also self-archiving a supplementary version, free for all, on the web (this is called the "green road" to OA, or simply "Green OA").

OA ≠ Gold OA Only (or even Primarily)

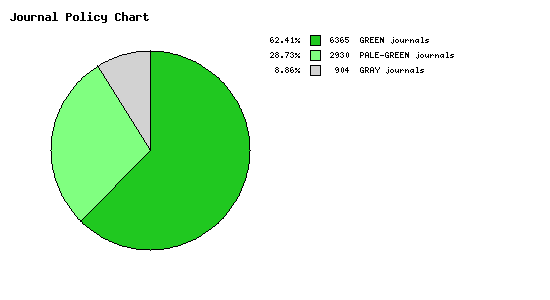

Gold OA publishing is probably what peer-reviewed journal publishing will eventually settle on. But for now, only about 3000 of the 25,000 journals are Gold OA, and the majority of the most important journals are not among that 3000.

Moreover, most of the potential institutional money for paying for Gold OA is currently still tied up in each university's ongoing subscriptions to non-OA journals. So if Gold OA is to be paid for today, extra money needs to be found to pay for it (most likely out of already insufficient research funds).

Yet what is urgently needed by research and researchers today is not more money to pay for Gold OA, nor a conversion to Gold OA publishing, but OA itself.

And 100% OA can already be provided by authors -- through Green OA self-archiving -- virtually overnight.

It has therefore been a big mistake -- and is still one of the big obstacles slowing progress toward OA -- to imagine that OA means only, or primarily, Gold OA publishing. (This mistake will keep getting made, repeatedly, in the Open Student blog too -- mark my words!)

The "Subversive Proposal"

It was in 1994 that the explicit "subversive proposal" was first made that if a supplementary copy of each peer-reviewed journal article were self-archived online by its author, free for all, as soon as it was published (as some authors in computer science and physics had already been doing for years), then we could have (what we would now call) 100% (Green) OA virtually overnight.

But that magic night hasn't arrived -- not then, in 1994, not in the ensuing decade and a half, and not yet today. Why not?

"Zeno's Paralysis"

There are at least 34 reasons why it has not yet happened, all of them psychological, and all of them groundless. The syndrome even has a name: "Zeno's Paralysis":

"I worry about self-archiving my article because it would violate copyright... or because it would bypass peer review... or because it would destroy journals... or because the online medium is not reliable... or because I have no time to self-archive..."Meanwhile, evidence (demonstrating the obvious) was growing that making your article OA greatly increases its usage and impact:

Yet still most authors' fingers (85%) remained paralyzed. The solution again seemed obvious: The cure for Zeno's Paralysis was a mandate from authors' institutions and funders, officially stating that it is not only OK for their employees and fundees to self-archive, but that it is expected of them, as a crucial new part of the process of doing research and publishing their findings in the online era.

"Publish or Perish: Self-Archive to Flourish!"

The first explicit proposals to mandate self-archiving began appearing at least as early as 2000; and recommendations for institutional and funder Green OA self-archiving mandates were already in the Self-Archiving FAQ even before it became the BOAI Self-Archiving FAQ in 2002, as well as in the OSI EPrints Handbook. But as far as I know the first officially adopted self-archiving mandate was that of the School of Electronics and Computer Science at the University of Southampton in 2002-2003.

Since then, 91% of journals have already given self-archiving their official blessing:

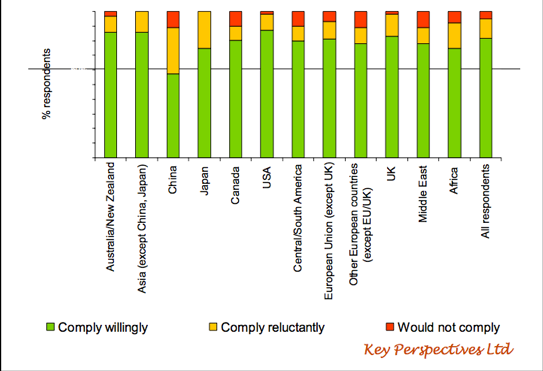

Yet Alma Swan's surveys of authors' attitudes toward OA and OA self-archiving mandates -- across disciplines and around the world -- have found that although authors are in favor of OA, most will not self-archive until and unless it is mandated by their universities and/or their funders. If self-archiving were mandated, however, 95% of authors state that they would comply, over 80% of them stating they would comply willingly.

Arthur Sale's analyses of what authors actually do with and without a mandate have since confirmed that if unmandated, self-archiving in institutional repositories hovers at around 15% or lower, but with a mandate it approaches 100% within about 2 years:

What Students Can Do to Hasten the Optimal and Inevitable but Long Overdue Outcome:

To date, 37 Green OA self-archiving mandates have been adopted worldwide, and 9 more have been proposed. Some of those mandates (such as that of NIH in the US, RCUK in the UK and ERC in Europe) have been very big ones, but most have been research funder mandates (22) rather than university mandates (12), even though virtually all research originates from universities, not all of it is funded, and universities share with their own researchers and students the benefits of showcasing and maximizing the uptake of their joint research output. Among the proposed mandates, two are very big multi-university proposals (one for all 791 universities in the 46 countries of the European University Association and one for all the universities and research institutions of Brazil), but those mandate proposals have yet to be adopted.

The world's universities are OA's sleeping giant. They have everything to gain from mandating OA, but they are being extremely slow to realize it and to do something about it. Unlike you students, they have not grown up in the online age, and to them the online medium's potential is not yet as transparent and natural as it is to you. You can help awaken your university's sense of its own need for OA, as well as its awareness of the benefits of OA, and the means of attaining them, by making yourselves heard:

1. OA Self-Archiving Begins At Home: First, let the professors and administration of your university know that you need and want (and expect!) research articles to be freely accessible to you on the web -- the entire research output of your own university to begin with (and not just the fraction of its total research output that your university can afford to buy-back in the form of journal subscriptions!) -- so that you know what research is being done at your own university, whom to study with, whom to do research projects with (and even to help you select a university for undergraduate or graduate study in the first place).

2. Self-Archive Unto Others As You Would Have Them Self-Archive Unto You: Second, point out the "Golden [or rather Green!] Rule" to the professors and administration of your university: If each university self-archives its own research output, this will not only make it possible for you, as students, to access the research output of all other universities (and not just the fraction of the total research output of other universities that your own university can afford to buy-in in the form of journal subscriptions!), so that you can use any of it in your own studies and research projects. Far more important, it will also make it possible for all researchers, at all universities (including your own), to access all research findings, and use and apply them in their own research and teaching, thereby maximizing research productivity and progress for the entire university community worldwide -- as well as for the tax-paying public that funds it all, the ones for whose benefit the research is being conducted.

But please make sure you get the rationale and priorities straight! The (successful) lobbying for the NIH self-archiving mandate was based in part on a premise that may have gone over well with politicians, and perhaps even with voters, but if thought through, it would not be able to stand up to close scrutiny. The slogan had been: We need to have OA so that taxpayers can have access to health research findings that they themselves paid for. True. And sounds good. But how many of the annual 2.5 million peer-reviewed research journal articles published every year in the 25,000 journals across all disciplines does that really apply to? How many of those specialized articles are taxpaying citizens likely ever to want (or even be able) to read! Most of them are not even relevant or comprehensible to undergraduate students.

Peer-To-Peer Access

So the overarching rationale for OA cannot be public access (though of course public access comes with the territory). It has to be peer-to-peer access. The peers are the research specialists worldwide for whom most of the peer-reviewed literature is written. Graduate students are entering this peer community; undergraduates are on the boundaries of it. But the general tax-paying public has next to no interest in it at all.

By the very same token, you will not be able to persuade your professors and administration that OA to the peer-reviewed research literature needs to be mandated because students have a burning need and desire to read it all! Students benefit from OA, but that cannot be the primary rationale for OA. Peer-to-peer (i.e., researcher to researcher) access is what has to be stressed. It is researchers worldwide who are today being denied access to the research findings they need in order to advance their research for the benefit of us all -- for the benefit of present and future students for whom the findings will be digested and integrated in textbooks, and for the benefit of the general public for whom the findings will be applied in the form of technological advances and medicines for illnesses.

So it is daily, weekly, monthly research impact that is needlessly being lost, cumulatively, while we keep dragging our feet about providing OA. That's what you need to stress to your professors and administration: all those findings that could not be used and applied and built upon because they could not be accessed by all or even most of their potential users, because it simply costs too much to subscribe to all or most of the journals in which they were published.

Updating the Academic Mandate for the Online Era

Point out also that OA policies always fail if they are merely recommendations or requests. The only thing that will embolden and motivate all researchers to self-archive is self-archiving mandates. "Mandate" is not a bad word. It doesn't mean "coercion" or punishment. It's all carrots, not sticks. Professors have a mandate to teach, and test, and give marks. They also have a mandate to do research, and publish (or perish!). If they teach well and do good research, they earn promotions, salary increases, tenure, research funding, prizes. If they don't fulfill their mandate, they don't. It's the same with students: You have a mandate to study and acquire knowledge and skills. If you don't fulfill your mandate, you don't earn good marks.

Mandates and Metrics

So it is not so much a matter of adopting a new "Green OA self-archiving mandate" for faculty, but of adapting the existing mandate. OA self-archiving is a natural adaptation to the PostGutenberg Galaxy and its technical potential (just as we adapted to reading and writing, printing, libraries and photocopying). It is no longer enough to just do, write up, and publish research: It has to be self-archived too. And the carrots are already there to reward doing it: Faculty are already evaluated on how well they fulfill their research performance mandate not only by counting their publications, but by assessing their impact -- for which one of the most important metrics is how much it is taken up, used and cited by further research. And citation counts are among the things that OA has been shown to increase.

It's rather as if -- as a part of your mandate as students -- you now had to submit your work online (as most of you already do!) instead of on paper in order to be evaluated and graded. Except it's even better than that for faculty, because self-archiving their work will actually increase their "grades."

In short, it's a win/win/win situation for your university, for your professors and for you, the students -- if only your university gets round, at long last, to fast-forwarding us to the optimal and inevitable: by mandating Green OA self-archiving. Rather than be puzzled and impatient that they have not done it already, you should provide a strong show of support for their doing it now. Be ready with the answers to the inevitable questions about how and why (and when and where). And beware, the 34-headed monster of "Zeno's Paralysis" is still at large, and growing back each head the minute you lop one off...

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Sunday, January 20. 2008

What About Open Access to Books?

Les Carr (U.Southampton) wrote:"Do ERC (or other short-term funders') research projects result in books? I am only an engineer who gets a bit lost outside STM, but I thought that books were written independently by researchers and that funded research projects had papers (and similar low-investment texts) as explicit research outputs?

NOTE: I am not asking whether books count as research outputs (they do) but whether they are the outputs of funded projects. I'll confine the scope of the question to single-author books, rather than multi-author books or edited collections."

(1) I would be very surprised if it were not the case that (in some disciplines at least) books count as the outputs of funded research. (Book citations certainly redound to an author's research credit as surely as article citations do.)

(1) I would be very surprised if it were not the case that (in some disciplines at least) books count as the outputs of funded research. (Book citations certainly redound to an author's research credit as surely as article citations do.)(2) Insofar as OA (and Green OA self-archiving mandates) are concerned, however, the relevant question is not whether books count as the outputs of funded research. (OA is for the outputs of research, whether or not the research is funded. And Green OA self-archiving mandates apply to the research output of a university's salaried academics, whether or not their research receives external funding, just as the university's publish-or-perish mandate applies to publications irrespective of whether they are the result of external funding.)

(3) Another way to put this is that even an academic who receives no external funding is institutionally funded to do research, inasmuch as research and publishing are part of his job-description.

(4) So the relevant variable is not funding but whether the research publication is an author give-away, written purely for the sake of research uptake, usage and impact -- the way all peer-reviewed articles are written -- or whether it is also written in the hope of royalty income (as many books are -- even though their hopes are usually not realized!)

(5) Perhaps trumping even the impact vs royalty question is the question of the cost of publication, and with it the question of whether a print run of the publication is desired.

(6) For better or worse, books are still preferentially published and read as conventional print-runs, rather than online-only, plus local print-offs by users.

(7) As long as that is true, the essential costs of producing and distributing a print-on-paper book will differ from the essential costs of producing and distributed a journal article (which can all be done online).

(8) Those essential costs of book publication need to be recovered regardless of whether the author hopes for royalty revenues over and above them.

(9) Some have suggested that making a book OA online will not hurt but help the sales of the print edition, but this is far from empirically established as the general rule (although it has happened in a few cases).

(10) Hence, although funders and institutions can and should mandate the self-archiving of peer-reviewed articles, they cannot and should not mandate the self-archiving of books.

(11) If it were proposed to extend Green OA self-archiving mandates to books, there would be (justified) resistance from both authors and publishers, and that would needlessly reduce the chances of adoption of what would otherwise have been an articles-only mandate.

(12) Once the 2.5 million articles published annually in the world's 25,000 peer-reviewed journals have been made OA by universal Green OA self-archiving mandates, the number of books and publishers that show an interest in pursuing a similar option will no doubt increase -- but that's not the same as subsuming books under the Green OA self-archiving mandates themselves.

Klaus Graf wrote:Much as I may wish it were otherwise, Klaus Graf unfortunately has it exactly backwards:"Stevan Harnad wrote: '(9) Some have suggested that making a book OA online will not hurt but help the sales of the print edition, but this is far from empirically established as the general rule (although it has happened in a few cases).'

"Looking at the evidence, it is far from empirically established as the general rule that a book OA online will hurt the sales. Please [cite] any valid articles or research confirming your prejudice. If you are stating a general rule you have to [prove] it."

The burden of proof is most definitely not on those who think that making books free online will hurt sales, to provide evidence that it is so. The burden is on those who think it is not so, to show that it is not.

The default or null hypothesis -- not just in this instance, but in the much more general one, of which books are just a special case -- is that, ceteris paribus, yes, if you make a digital version of a product available free for all online, you will hurt its sales (digital and analogue). There may be exceptions, but they have to be demonstrated.

And evidence is a tricky matter, especially for a negative hypothesis. It is not sufficient evidence that a platypus does not lay eggs, to show photos of some platypuses, not laying eggs.

For journal articles, although the evidence so far seems to be that Green OA self-archiving has not caused cancellations, it remains a possibility that it eventually will. However, as has been pointed out repeatedly, in that very special case, it does not matter, either way:

But none of that carries over to books and book publishing -- neither to books in general, nor to scholarly/scientific books in particular.i. because research usage and impact is far more important than sustaining the current journal-publishing cost-recovery model;

ii. because authors, their institutions and funders are unanimous in insisting on the priority of research usage and impact; and

iii. because Gold OA journal publishing is there to take over if and when the subscription model should become unsustainable.

Neither for journal articles nor for books can free online access be attained through wishful thinking and righteous indignation alone. Fortunately, for journal articles, it needn't be.(a) It is not true that books are mostly written only for research usage and impact. (Most are also written in the hope of royalty income.)

(b) It is not true that book authors all or even mostly want to give them away free online.

(c) It is not clear that book authors or readers no longer desire a paper edition.

(d) It is not clear that there is a viable, sustainable Gold OA publishing model for books yet, even if authors did want to give their books away and no one wanted the print edition any more.

(e) And, most important, it has not been shown that giving away the online edition will not hurt print sales (or even make them unsustainable); it has only been shown not to hurt some books' print sales, so far.

Let us not, then, needlessly handicap the strong special case for OA -- which covers all of peer-reviewed journal articles and authors without a single exception -- with the unneeded extra baggage of the uncertain, untested and equivocal case of books. Some books may eventually go the way of OA too; but right now, when the research community is finally on the verge of successfully inducing its funders and universities worldwide to adopt Green OA self-archiving mandates, this is definitely not the time to try to change the rules, raise the stakes, and insist on mandating book-deposit too.

Leave book-deposit as an author option, like access-setting itself, and give OA, already so grotesquely overdue, the chance to come into its own at long last.

Klaus Graf wrote:I am afraid that Klaus Graf has not understood what is meant by the default or null hypothesis: To demonstrate [proof is possible only in mathematics] that the null hypothesis is false you need to provide compelling evidence to the contrary. The null hypothesis is that vitamin C does not cure cancer. The evidential burden is on those who think it does, to provide compelling evidence that it does, not on those who think it doesn't, to provide evidence that it doesn't. (Most things do not cure cancer, by default. No one has to give evidence that vitamin C does not cure cancer.) The occasional report that some people who were diagnosed with cancer took vitamin C and are still alive is not compelling evidence. The jury is still out on vitamin C. It has been out for a long time."Is there any empirical proof for this default hypothesis? There is only empirical evidence for the contrary. It's purely nonsense to state a "default hypothesis" if empirical facts should be given."

(Apologies for the shrillness of the example. I did not want to use miracles or telekinesis, because that would be too exacting and dismissive. I just wanted to give an illustration of the evidential burden on the null hypothesis with a case where -- some believe -- closure has not yet been reached. Another example would be the legal presumption of innocence until compellingly "proved" guilty: There is no burden to "prove" innocence: it is the default hypothesis.)

As with vitamin C, with book sales it is not sufficient merely to cite self-selected positive evidence; it is necessary to do systematic controlled comparisons, on sufficiently large and representative samples: N new books, selected at random, half of them then made freely accessible online, half not, and then a comparison of their sales for several years. Perhaps even a replication or two...

Pablo Ortellado wrote:Mandatorily "in many cases"? How many? And which? and who decides, how?"You may call it OA or not, but books in many cases should be mandatorily made available on the Internet..."

Please take a moment to reflect.

The substantive issue is not what we do and don't call "OA."

The issue is what we can and cannot consensually mandate (and what a mandate is).

After much too long a delay, the momentum is finally gathering for funders and universities to adopt Green OA mandates to deposit all peer-reviewed research journal articles in OA repositories. (Not "in many cases": all, without exception: that's why/how it's a mandate.)

The reason those mandates proved possible was that all the authors of all those articles (as well as their universities and their funders) without exception, wanted to give away those articles for free online.

None of them sought royalty revenues or print sales -- they sought only maximal research impact.

None of this is true without exception, or even majoritarily, of books. It is true of some authors of some books. And those authors are all free to deposit them in their OA IR if they wish.

(Not only are the same OA IRs there, ready for books to be deposited into them too; they can even be deposited IDOA, if the author wishes: Closed Access but with the option of emailing one copy to any requesters the author approves.)

(Not only are the same OA IRs there, ready for books to be deposited into them too; they can even be deposited IDOA, if the author wishes: Closed Access but with the option of emailing one copy to any requesters the author approves.) And as with Gold OA journal publishing, book publishers are more than welcome to experiment with offering free online access, as National Academies Press does, extremely successfully and valuably.

But if you insist on including books in the deposit mandates, you will simply prevent the adoption of the mandates themselves, because they were predicated on consensus among authors, their institutions and their funders that their articles were intended as give-aways all along (even before the online era). There is no such consensus on books (in fact, I suspect, far from it).

Hence on no account should we needlessly jeopardize the spread of Green OA self-archiving mandates today, just when adoptions are at last beginning to gather speed, by raising the goal-posts, this time to a height for which the research community can no longer sustain its natural consensus, by now declaring that book deposit is to fall under the OA mandates too.

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Saturday, October 20. 2007

EurOpenScholar Launched by European University Rectors

A Conference of Rectors of European Universities convened in Liège on 18 October 2007 by the Rector of the University of Liège, Bernard Rentier, has launched EurOpenScholar:

A Conference of Rectors of European Universities convened in Liège on 18 October 2007 by the Rector of the University of Liège, Bernard Rentier, has launched EurOpenScholar:"a showcase and a tool for the promotion of Open Access (OA) in Europe. It will be a consortium of European universities resolved to move forward on OA and to try to convince the largest possible number of researchers, their institutions and their European Funding Agencies to engage now in what will undoubtedly be the mode of communication of tomorrow. The transitional period will be the most challenging. Our goal is to facilitate and thereby accelerate as much as possible the transition to the OA era.Translated from text of Bernard Rentier, Rector, Université deLiège.

"The EurOpenScholar web site, hosted by the ULg, will provide an information-gathering service concerning OA institutional repositories and OA journals, with a discussion forum on OA as well as the methods emerging in the field of scientometrics (research performance and impact measurement, ranking and analysis).

"EurOpenScholar's primary objective will be to open researchers' eyes to the new ways of promoting the spread of knowledge and of assessing research progress and performance in the OA era. This will contribute to the advancement of research in Europe and to the promotion of European research and researchers.

"In addition, EurOpenScholar will address itself to research managers, funding agencies, national and local research policy-makers, the R&D industry, the media, and the general public, facilitating synergies and technology transfer and providing an effective channel for the communication of real science to the public, either directly or through the media."

Saturday, August 18. 2007

The Coming Revolution in Scholarly Communications & Cyberinfrastructure

The Coming Revolution in Scholarly Communications & CyberinfrastructureCTWatch Quarterly Volume 3 Number 3 August 2007

Introduction

Lee Dirks, Microsoft Corporation; Tony Hey, Microsoft Corporation

The Shape of the Scientific Article in The Developing Cyberinfrastructure

Clifford Lynch, Coalition for Networked Information (CNI)

Next-Generation Implications of Open Access

Paul Ginsparg, Cornell University

Web 2.0 in Science

Timo Hannay, Nature Publishing

Reinventing Scholarly Communication for the Electronic Age

J. Lynn Fink, University of California, San Diego;

Philip E. Bourne, University of California, San Diego

Interoperability for the Discovery, Use, and Re-Use of Units of Scholarly Communication

Herbert Van de Sompel, Los Alamos National Laboratory;

Carl Lagoze, Cornell University

Incentivizing the Open Access Research Web: Publication-Archiving, Data-Archiving and Scientometrics

Tim Brody, University of Southampton, UK;

Les Carr, University of Southampton, UK;

Yves Gingras, Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM);

Chawki Hajjem, Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM);

Stevan Harnad, Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM); University of Southampton, UK;

Alma Swan, University of Southampton, UK; Key Perspectives

The Law as Cyberinfrastructure

Brian Fitzgerald, Queensland University of Technology, Australia;

Kylie Pappalardo, Queensland University of Technology, Australia

Cyberinfrastructure For Knowledge Sharing

John Wilbanks, Scientific Commons

Trends Favoring Open Access

Peter Suber, Earlham College

Saturday, August 4. 2007

Ethics of Open Access to Biomedical Research: Just a Special Case of Ethics of Open Access to Research

1. All peer-reviewed research articles are written for the purpose of being accessed, used, applied and built upon by all their potential users, everywhere, not in order to generate royalty income for their author (or their publisher). (This is not true of writing in general, e.g., newspaper and magazine articles by journalists, or books. It is only true, without exception, of peer-reviewed research journal articles, and it is true in all disciplines, without exception.)SUMMARY: The ethical case for Open Access (OA) (free online access) to research findings is especially salient when it is public health that is being compromised by needless access restrictions. But the ethical imperative for OA is far more general: It applies to all scientific and scholarly research findings published in peer-reviewed journals. And peer-to-peer access is far more important than direct public access. Most research is funded to be conducted and published, by researchers, in order to be taken up, used, and built upon in further research and applications, again by researchers, for the benefit of the public that funded it -- not in order to generate revenue for the peer-reviewed journal publishing industry (nor even because there is a burning public desire to read [much of] it). Hence OA needs to be mandated for all research.

2. Research productivity and progress, and hence researchers' careers, salary, research funding, reputation, and prizes all depend on the usage and application of their research findings ("research impact"). This is enshrined in the academic mandate to "publish or perish," and in the reward system of academic research.

3. The reason the academic reward system is set up that way is that that is also how research institutions and research funders benefit from the research output they produce and fund: by maximizing its usage and impact. That is also how the cumulative research cycle itself progresses and grows, along with the benefits it provides for society, the public that funds it: In order to be used, applied, and built upon, research needs to be accessible to all its potential users (and not only to those that can afford access to the journals in which the research happens to be published.).

4. Open Access (OA) -- free online access -- has been demonstrated to increase research usage and impact by 25%-250% or more. This "OA Advantage" has been found in all fields: natural sciences, biomedical sciences, engineering, social sciences, and humanities.

5. Hence it is true, without exception, in all fields, that the potential research benefit is there, if only the research is made OA.

6. OA has only become possible since the onset of the online era.

7. Research can be made OA in two ways:

(7a) Research can be made "Gold OA" by publishing it in an OA journal that makes it free online (with some OA journals, but not all, covering their costs by charging the author-institution for publishing it rather than by charging the user-institution for accessing it; many Gold OA journals today still continue to cover their costs via subscriptions to the paper edition).8. Despite its benefits to research, researchers, their institutions, their funders, the R&D industry, and the tax-paying public that funds the research, only about 15% of researchers are spontaneously self-archiving their research today (Green OA). (A somewhat lower percentage is publishing in Gold OA journals, deterred in part by the cost.)

(7b) Or research can be made "Green OA" by publishing it in a conventional, non-OA journal, but also self-archiving it in the author's Institutional Repository, free for all.

9. Only Green OA is entirely within the hands of the research community. Researchers' funders and institutions cannot (hence should not) mandate Gold OA; but they can mandate Green OA, as a natural extension of their "publish or perish" mandate, to maximize research usage and impact in the online era. Institutions and funders are now actually beginning to adopt Green OA mandates especially in the UK, and also in Europe and Australia; the US is only beginning to propose Green OA mandates.

10. Some publishers are lobbying against Green OA self-archiving mandates, claiming it will destroy peer review and publishing. All existing evidence, however, is contrary to this. (In the few fields where Green OA already reached 100% some years ago, the journals are still not being canceled.) Moreover, it is quite clear that even if and when 100% Green OA should ever lead to unsustainable subscription cancellations, journals can and will simply convert to Gold OA and institutions will then cover their own outgoing Gold OA publishing costs by redirecting part of their windfall subscription cancellation savings on incoming journal articles to cover instead the Gold OA publishing costs for their own outgoing journal article output. The net cost will also be much lower, as it will only need to pay for peer review and its certification by the journal-name, as the distributed network of OA Institutional Repositories will be the online access-providers and archivers (and the paper edition will be obsolete).

11. One of the ways the OA movement is countering the lobbying of publishers against Green OA mandates is by forming the "Alliance for Taxpayer Access." This lobbying group is focusing mainly on biomedicine, and the potential health benefits of tax-payer access to biomedical research. This is definitely a valid ethical and practical rationale for OA, but it is definitely not the sole rationale, nor the primary one.

12. The primary, fundamental and universal rationale for OA and OA mandates, in all disciplines, including biomedicine, is researcher-to-researcher access, not public access (nor even educational access). The vast majority of peer-reviewed research in all disciplines is not of direct interest to the lay public (nor even to students, other than graduate students, who are already researchers). And even in biomedical research, what provides the greatest public benefit is the potential research progress (leading to eventual applications that benefit the public) that arises from maximizing researcher-to-researcher access. Direct public access of course comes with the OA territory. But it is not the sole or primary ethical justification for OA, even in biomedical research.

13. The general ethical rationale and justification for OA is that research is funded, conducted and published in order to be used and applied, not in order to generate revenue for the journal publishing industry. In the paper era, the only way to achieve the former was by allowing access to be restricted to those researchers whose institutions could afford to subscribe to the paper edition. That was the only way the true and sizable costs of peer-reviewed research publishing could be covered at all, then.

14. But in the online era this is no longer true. Hence it is time for the institutions and funders who employ the researchers and fund the research to mandate that the resulting journal articles be made (Green) OA, to the benefit of the entire research community, the vast R&D industry, and the tax-paying public. (This may or may not eventually lead to a transition to Gold OA.)

15. It is unethical for the publishing tail to be allowed to continue to wag the research dog. The dysfunctionality of the status quo is especially apparent when it is public health that is being compromised by needless access restrictions, but the situation is much the same for all scientific and technological research, and for scholarship too, inasmuch as we see and fund scholarly research as a public good, not as a subsidy to the peer-reviewed journal industry.

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Sunday, April 29. 2007

Open Access Is Not Just A Public Health Matter

The interest and commitment of some of the supporters of Open Access (OA) is derived from and motivated by the importance of making health-related research accessible to those who need it: patients, family, researchers.

The interest and commitment of some of the supporters of Open Access (OA) is derived from and motivated by the importance of making health-related research accessible to those who need it: patients, family, researchers. This is certainly an important component of OA, and perhaps the aspect that most directly touches our lives. But if OA is seen or portrayed as being mainly a health-related matter, it not only leaves out the vast majority of OA's target content-- which is all research in all research areas, from the physical and biological sciences to the social sciences and the humanities -- but it even under-serves OA's potential benefits to health research itself.

Even the "tax-payer access" aspect of OA, though important, is not quite representative, because the primary benefit of OA to the tax-payer who pays for the research is not that it makes the research freely accessible to the tax-payer (although it does indeed do that too!), but that it makes the research freely accessible to the researchers for whom it was mostly written, but many of whom cannot afford access to it -- so that they can use, apply and build upon that research, in their own research -- to the benefit of the tax-payers who funded it and for whose sake the research is conducted. Again, a focus on the need for direct public access to health-related research leaves out the vast majority of research that is not health-related and that the public has no particular interest in reading -- but a great interest in making accessible to those who can use and build on it so as to increase research progress, which may in its turn eventually lead to applications that benefit the public.

Paradoxically, it is in recognizing and supporting OA's much more general research enhancing mission that we can also best support its health-related potential.

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

« previous page

(Page 3 of 3, totaling 27 entries)

EnablingOpenScholarship (EOS)

Quicksearch

Syndicate This Blog

Materials You Are Invited To Use To Promote OA Self-Archiving:

Videos:

audio WOS

Wizards of OA -

audio U Indiana

Scientometrics -

The American Scientist Open Access Forum has been chronicling and often directing the course of progress in providing Open Access to Universities' Peer-Reviewed Research Articles since its inception in the US in 1998 by the American Scientist, published by the Sigma Xi Society.

The American Scientist Open Access Forum has been chronicling and often directing the course of progress in providing Open Access to Universities' Peer-Reviewed Research Articles since its inception in the US in 1998 by the American Scientist, published by the Sigma Xi Society.

The Forum is largely for policy-makers at universities, research institutions and research funding agencies worldwide who are interested in institutional Open Acess Provision policy. (It is not a general discussion group for serials, pricing or publishing issues: it is specifically focussed on institutional Open Acess policy.)

You can sign on to the Forum here.

Archives

Calendar

|

|

May '21 | |||||

| Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun |

| 1 | 2 | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

| 31 | ||||||

Categories

Blog Administration

Statistics

Last entry: 2018-09-14 13:27

1129 entries written

238 comments have been made