Quicksearch

Your search for double returned 140 results:

Thursday, March 15. 2007

Gold Fever and Trojan Folly

On Sat, 10 Mar 2007, Jan Velterop, of Springer Open Choice, wrote in liblicense:

SUMMARY: Jan Velterop recommends, without any supporting argument, that at a time when publication costs are still being fully covered by subscriptions, research funders and institutions should not mandate Green OA self-archiving, because that would (according to Jan) be merely a "cheap palliative," not a "full cure".

A full cure would be to double-pay for Gold OA (double, because publication costs are still being covered by subscriptions) until publishers voluntarily pass on their excess revenues by gradually discounting and eventually phasing out subscriptions.

Our disease, it appears, is not our lack of OA (for mandating Green OA would provide 100% OA); our disease is our paying for publication in the wrong way (via subscriptions rather than publication charges). And the reason the "cheap palliative" of mandating Green OA is a bad idea (according to Jan) is that it might cause subscriptions to be cancelled.

What Jan does not explain is why not-paying for publication in the right way is our disease, rather than not-having research access -- for it is access to research that the OA movement is all about, and 100% research access -- not something else -- that OA is meant to provide.

Nor does Jan explain why 100% Green OA is not a cure for this lack of research access: Either the 100% OA generated by the Green OA mandates will eventually cause subscriptions to be cancelled so they no longer cover publication costs or it will not. If it does not, then Green OA mandates will merely have generated 100% OA. If it does, then Green OA mandates will also have generated a transition to Gold OA, along with releasing the money (the windfall subscription savings) out of which to pay the Gold OA publication charges without having to find the extra money to double-pay (for publication charges on top of subscriptions). It is not at all clear why Jan regards this as "cheap palliative care" rather than a "full cure," either way.

If, that is, Jan is really for OA, rather than something else.

JV: "The Howard Hughes (HHMI-Elsevier) deal is not a setback for open access, even if it is not the greatest imaginable step forwards perhaps."It is not a setback for the minuscule number of articles for which HHMI will finance paid (Gold) OA. It is a setback for all the other articles that could be made (Green) OA through mandated author self-archiving, for free, while subscriptions are still continuing to pay the publication costs.

It is not only a waste of money, but it plays into the hands of those who are trying to delay or derail Green self-archiving mandates at all costs.

JV: "To knock the HHMI for getting into this deal is short-sighted."It is HHMI that is being short-sighted (and gullible). HHMI ought instead simply to mandate Green OA self-archiving, and to leave it at that.

JV: "And subject lines like 'Trojan Horse' with their insidious negativity raise the suspicion that the agenda of some list participants is not really 'open access', but a desire to get rid of publishers or of the notion that publishing, including open access publishing, actually costs money."Nonsense. Open Choice is a Trojan Horse if it is taken as a pretext for paying for Gold OA instead of mandating Green OA. No one is trying to get rid of publishers. We are trying to get rid of access-barriers. Green OA does just that. And while subscriptions are still being (amply) paid for, no one is unaware of the fact that publishing costs money. What is urgently needed today is not money to pay for Gold OA, but mandates to provide Green OA.

JV: "It's a delusion that one can get open access by self-archiving mandates that imply having to rely on librarians to keep paying for subscriptions to keep journals alive."Institutions are paying for subscriptions today. That is no delusion.

There is little OA today. That is no delusion.

Green self-archiving mandates will generate 100% OA. That is no delusion.

What happens to subscriptions after that is speculation, not delusion.

JV: "Or is the idea that librarians keep paying for journals of which the articles are available with open access part of the proposed mandates?"Institutions are paying for librarians today. That is not proposed; that is already going on.

What is not already going on is OA self-archiving.

That is what the Green mandates are for.

Whether and when institutions will cancel subscriptions because of mandated Green OA is a purely speculative matter, today. What is not speculative is that if and when institutions ever do cancel subscriptions, that money will then be freed to pay for Gold OA costs; not before. Nor is it speculation that Green OA will already have provided 100% OA by then.

JV: "Authors can self-publish easily these days and provide open access to their articles to their hearts' content."Why is Jan telling us this? OA is not -- and never has been -- about self-publishing; nor is it about unpublished articles. It is about providing Open Access to peer-reviewed, published articles.

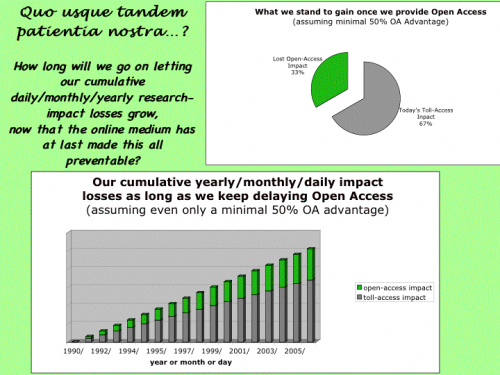

JV: "Once they involve a publisher, though, they don't do that out of altruistic motives."No. Nor does the publisher. But publishers are being paid in full, today, by subscriptions, whereas Open Access is not being provided, today. And consequently research impact is needlessly being lost today.

It would not just be altruism but profligacy to double-pay for Gold OA today. And it would be (and is) not altruistic but foolhardy in the extreme to continue doing without OA, and with the attendant daily loss in research impact and progress, for failure to mandate Green OA.

(Foolhardy for the research community, and the public that funds it, I mean: Not necessarily foolhardy for the publishing community!)

JV: "They don't 'give' their articles to publishers. They come to ask for a 'label', a 'mark', an official journal reference that makes their article from a piece of text, perhaps interesting, but not recognised by the academic community, into a formally peer-reviewed and published article. It's not the publishers that compel them to do that."I don't know why we are being regaled with all this rhetorical complexity: Researchers submit their papers to journals for two reasons:

(1) to get them peer-reviewed andThat is what subscriptions are already paying for. OA is for those would-be users who cannot afford access to the subscription version.

(2) to provide access to them.

It is not authors who seek or get the revenues from subscriptions, it is publishers. No altruism on either side. And the only thing missing, in the online age, is OA. And Green OA mandates will provide that.

JV: "And publishers cannot provide those services, on the scale they are needed, on a philanthropic basis."No one is asking them to: Subscriptions are paying, amply. OA is about those users who cannot afford access to the subscription version.

JV: "This may be possible for a number of small journals, and where it is possible it deserves to be done that way and probably is already."Jan (and the publishing community) keep talking about journals and journal cost-recovery models. Fine.

The research community is talking about OA, and impact-loss-recovery methods.

The only tried, tested, successful method of impact-loss-recovery within immediate reach is mandating OA self-archiving. That has nothing to do with journal cost-recovery models. Jan is talking at cross-purposes with OA, with his fixation on payment models (when there is no non-payment problem today, whereas there is a no-access problem today).

In thus talking at cross-purposes, Jan (and those of the same persuasion) are standing in the way of a tried, tested, successful, and immediately reachable means of solving the access problem. They are instead promoting a Trojan Horse.

JV: "But the worldwide scientific enterprise needs sustainable large-scale industrial-strength publishing to deal with the publication of more than a million new articles a year (and in terms of submissions a multiple of that, given that most papers are rejected at least once)."Can we transfer the problem of the "sustainability of large-scale industrial-strength publishing" to another venue than discussions of OA?

OA is an immediate, pressing, and immediately solvable problem for research and researchers. Its solution is for research institutions and funders to mandate Green OA, as a few have already begun doing, others have proposed to do, and researchers and institutions have petitioned them to do.

The quest for a solution to the "the problem of the sustainability of large-scale industrial-strength publishing" can proceed in parallel with the quest for OA, but it should not be conflated with it, or get in the way of it.

To oppose Green OA mandates and urge "Open Choice" in their stead is precisely the Trojan Horse against which I am warning.

JV: "The HHMI deal is a very positive step towards sustainable open access and should be recognised for that. The 'cure' of OA publishing is to be preferred to the 'palliative' of self-archiving. The derision that funding agencies suffer who put open access first, and not cost reduction, is uncalled-for."Who on earth is talking about cost-reduction?

The disease is needless, ongoing, online research access/impact loss. The cure is OA. Green OA is OA. It might be merely a "palliative" for "the problem of the sustainability of large-scale industrial-strength publishing" but it is a cure for the disease of research access/impact loss.

What deserves exposure and derision is the attempt to deter and devalue and deride a sure and reachable immediate cure for the disease of research/impact loss in the name of some other uncured "disease" that has next to nothing to do with the research community's immediate, pressing, and solvable access/impact needs today.

JV: "If a full, safe cure for a disease is possible, though not necessarily cheaper than lifelong symptom-management and the real possibility of a much shorter life, is it better to go for cheap palliative care than for this full cure?"As usual, we are talking about two different "diseases." One -- "the sustainability of large-scale industrial-strength publishing" -- is a long-term, hypothetical money-matter with which the publishing community is concerned; the other -- research access/impact loss -- is an immediate, urgent, ongoing practical research-matter with which the research community is concerned -- and it has an immediate, practical solution: Mandated Green OA.

To deter, defer or derail the research community's solution to the research community's problem, by portraying the publishing community's industrial long-term sustainability problem as if it were the same problem as the research community's immediate access/impact problem is simply false and misleading.

To oppose the research community's immediately reachable solution to its access/impact problem (mandated Green OA) in favour of paying for Gold OA today is nothing more nor less than what I have called it: The promotion of a Trojan Horse.

Caveat Emptor.

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Don't Count Your (Golden) Chickens Before Your (Green) Eggs Are Laid

SUMMARY: Michael Kurtz writes:

Research is growing. (True, but that is independent of OA.)

Publication costs are not a large percentage of total research costs. (True, but publication costs are already being paid in full, today, by subscription fees; any new publication charges today hence mean additional funds redirected from research -- or from elsewhere -- to double-pay, unless the existing subscription fees are redirected toward paying the publication charges.)

OA enhances research progress. (True)

Author publication charges are not new (in some fields). (True, but new OA publication charges, today, would be new, and additional, unless their payment was redirected from subscription savings.)

Mandated Green OA could cause subscription collapse. (Possibly, but if it did, that would simultaneously release the subscription savings to be redirected to pay for Gold OA publication charges [probably reduced to just the cost of peer review]; and meanwhile we would already have 100% [Green] OA, either way.)

In some fields, Central Repositories (CRs) like Arxiv have a larger Green OA percentage of total research output than Institutional Repositories (IRs). (A few fields do provide Green OA, unmandated, today, but most don't; that's why we need mandates; IRs that mandate Green reach 100% OA within about two years; institutions and funders mandate; "fields" do not; institutions wish to record, showcase, and maximize the impact of their own research output; "fields" do not; CRs can harvest from IRs; the locus of deposit for mandates should be researchers' own IRs.)

I would dearly love to adhere to my dictum "Hypotheses non Fingo," but with hypotheses being finged willy-nilly by others -- at the cost of neglecting or even discouraging tried-and-tested practical (and a-theoretical) action (i.e., Green OA mandates) -- I am left with little choice but to resort to counter-hypothesizing:

On Wed, 14 Mar 2007, Michael Kurtz [MK] wrote in the American Scientist Open Access Forum:

MK: "(A) THE CURRENT SITUATION. The quantity of scientific research has been increasing exponentially for several generations. This increase, roughly an order of magnitude during my lifetime (~4% per year, essentially the same as the growth in the global economy), has been mediated and enabled by the existing system for scientific communication, namely toll access journals and libraries."Correct.

And another thing has happened in the past generation or so: The birth of the Net and Web, making it possible to supplement toll-access with author-provided free online access (Green OA).

That development has next to nothing to do with the growth in the number of articles, nor with the price of journals. It has to do with the possibility of supplementing toll access with free online access.

MK: "(B) THE CURRENT COSTS. Direct costs for journals are remarkably small, about 1% of the total research and development budget (1). This compares with other costs involved such as (2) unpaid refereeing and editing 1% and the non-acquisition costs of a library, 2%. Possible changes to the direct cost of journals, up or down, are likely to be smaller than the error in estimating the yearly inflation adjustments."Correct, but irrelevant to the question of providing free online access for would-be users who cannot afford toll access.

Yes, if the money currently being spent on user-institution access-tolls were instead redirected to pay for author-institution publication charges, no more or less money would be spent, and online access would be free (Gold OA). But that is happening far too slowly, and does not depend only on the researcher community. Supplementing toll access with free online access (Green OA) is entirely in the hands of the research community.

Providing supplementary online access for free can be accelerated to 100% within a year or two through the adoption of research funder and university Green OA self-archiving mandates. That too is in the hands of the research community. Until it is done, research usage and impact continues to be lost, needlessly, daily.

MK: "(C) THE POSSIBLE BENEFIT OF OPEN ACCESS. The purpose of OA is to increase the amount and quality of research. The growth rate of research is currently ~4%; if OA is a massive success, it could perhaps increase this growth rate by 10%, which would be a yearly increment of 0.4% of total research. It may be expected that the greatest effect of OA would be in cross-disciplinary research, such as Nanotechnology."(The quantitative estimates are still rather speculative. [Here are some more.] But let us agree that providing OA will indeed increase research productivity and progress.)

MK: "(D) THE RISK OF OPEN ACCESS. By substantially changing the economics of journal publishing OA risks the catastrophic financial collapse of some publishers. This is especially true for the mandated 100% green OA path."If and when mandated 100% Green OA does cause subscriptions to be cancelled to unsustainable levels, the resultant user-institution subscription savings can be redirected to pay instead for author-institution publication charges (Gold OA).

Green OA mandates, by research institutions and funders are possible (indeed actual), and can grow institution by institution and funder by funder.

If Gold OA (with its attendant redirection of subscription funds) can be mandated at all, it certainly cannot be done institution by institution and funder by funder (with 24,000 journals, 10,000 institutions, and hundreds of public funders worldwide). Redirection, if it is to occur at all, has to be driven by Green OA mandates.

Pre-emptive redirection of funds (by an institution or a funder) toward Gold OA, without being preceded by 100% Green OA, is a waste of money, effort and time, today. (After 100% Green OA it is fine, as long as there is no double-paying, through redirection of research money instead of subscription money.)

MK: "(E) CURRENT GREEN MODELS. There are basically two types of Green repository: centralized, such as arXiv, and distributed, as the institutional repositories. Only arXiv has much of a track record. After more than 15 years arXiv only has more than half the refereed articles in the two subfields of High Energy Physics and Astrophysics; only HEP has more than 90%. It does not appear that there is any subfield of science where the existing institutional repositories contain more than half of the refereed literature."It is completely irrelevant where the free online articles are located. (The IRs and CRs are all OAI-interoperable.) What matters is that 100% of articles should be free online. Spontaneous central archiving has not reached 100% in 15 years (where it is being done at all). The natural and optimal place for institutions to mandate the deposit of their own article output is in their own IRs. That covers all of research output space. Mandated IRs fill within two years. Research funder mandates should reinforce the institutional mandates. If CRs are desired, they can harvest from the IRs.

MK: "(F) CURRENT GOLD MODELS. Page charges have existed for decades as a method of financing journals; while their use has been in decline for some time several venerable titles use them, in whole or in part, and there are several new, page charge funded, OA journals. Direct subsidies, by scholarly organizations and funding agencies, have long been used to support scientific publishing. Nearly all technical reports series are funded in this manner."Publication charges are currently being fully covered by subscriptions, but access is not open to all would-be users, hence research usage and impact (productivity and progress) are being needlessly lost.

There is no realistic way (nor is there a will) to redirect the subscription money currently being spent by 10,000 user-institutions worldwide for various subsets of 24,000 journals toward instead paying author-institution Gold OA publication charges. Hence the only money that can be redirected to pay for Gold OA today (by institutions or funders) is money that is currently being spent on research or other expenses, thereby effectively double-paying for publication (and at a time when subscription costs are already inflated).

Hence if the goal is 100% OA, the way to reach it is through institutions and funders mandating Green OA.

After that, redirect toward Gold OA to your heart's content. But to do so before that, or instead of that, is pure folly.

P.S. The journal affordability problem and the research accessibility problem are not the same problem. Green OA mandates will solve the research accessibility problem for sure. They may or may not cause unsustainable cancellations, but either way they will ease, though not solve, the journal affordability problem (by making the decision about which journal subscriptions to purchase from a limited serials budget into less of a life-or-death question, given that 100% Green OA is there as a safety net for accessing whatever an institutions cannot afford). Green OA, if it causes cancellations, will also cause cost-cutting and downsizing (the IRs can take over the access-provision and archiving load, leaving the journals with peer-review management as their only service), making (post-Green) Gold OA more affordable than it would be today (pre-Green).

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Tuesday, March 13. 2007

Double-Paying for Optional Gold OA Instead of Mandating Green OA While Subscriptions Are Still Paying for Publication: Trojan Folly

"I see the Howard Hughes Medical Institute HHMI-Elsevier deal [in which HHMI pays for for "gold" OA publishing of its funded research] as a major set back for institutional self-archiving as it muddies the green landscape, which I am sure is one of the underlying intents of Elsevier and other publishers in the STM group. I suspect more publishers may follow suit and reverse their stand on green if they think there is money to be made. Something needs to happen quickly. The Trojan Horse has proved to work, unfortunately. What should we do?"I know exactly what needs to be done, and it has been obvious all along: The mandates have to be taken completely out of the hands of publishers and out of the reach of embargoes, and there is a sure-fire way to do it:

The mandates must be Immediate-Deposit/Optional-Access (ID/OA) mandates.

Let the access to the deposit be provisionally set as Closed Access wherever there is the slightest doubt. That way publishers have no say whatsoever in whether or when the deposit itself is done. Then let the EMAIL EPRINT REQUEST button -- and human nature, and the optimality of OA -- take care of the rest of its own accord, as it will. If only we have the sense to rally behind ID/OA.

Generic Rationale and Model for University Open Access Self-Archiving Mandate: Immediate-Deposit/Optional Access (ID/OA)It is as simple as that. But we have to unite behind ID/OA, and give a clear consistent message (and for that we have to first clearly understand ID/OA!)

If we keep flirting with embargoes and Gold and publishing reform and funding instead of univocally rallying behind the ID/OA mandate that will immunise us from publisher policies and further embargoes, we will get nowhere, and indeed we will lose ground.

It is as simple as that.

(P.S. HHMI got into this because of another legacy of folly, not originating with HHMI: The irrational insistence on central deposit in PubMed Central instead of local deposit in each researcher's own Institutional Repository. A Central Repository can -- on a far-fetched construal -- be argued to be a rival 3rd party re-publisher. Not so the author's own institution, archiving its own research.)

Optimizing OA Self-Archiving Mandates:Stevan Harnad

What? Where? When? Why? How?

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Monday, December 25. 2006

On SPARC's Advice to the Australian Research Council

Across the years, SPARC has often been a great help to the Open Access movement. But SPARC could help so much more if it could take advice, in addition to giving it (sometimes with insufficient information and reflection):

SUMMARY: The Australian Research Council (ARC) has proposed to mandate OA self-archiving by its fundees. SPARC has advised ARC (1) to require retaining non-exclusive rights as well, (2) to require OA self-archiving within 6 months of publication, and (3) to earmark ARC funds for OA journal publication costs, so OA can be immediate. I suggest instead (1) that to mandate self-archiving it is neither necessary nor desirable to mandate retaining non-exclusive rights at this time, (2) that deposit should be mandated immediately upon publication, with any allowable 6-month delay applying not to the timing of the deposit itself but only to the timing of the setting of access to the deposit (as Open Access rather than Closed Access), and (3) that it is neither desirable nor necessary at this time to earmark ARC funds to pay to publish in OA journals for immediate OA: Institutional Repositories' EMAIL EPRINT REQUEST button will be sufficient to tide over user needs during any 6-month embargo interval between deposit and OA. (Australia's OA specialist Arthur Sale concurs.)

- A Role for SPARC in Freeing the Refereed Literature (Jun 2000)

- SPARC reply

- Comments on the SPARC Position Paper on Institutional Repositories (Aug 2002)

- New SPARC/ARL/ACRL Brochure on Open Access (Jun 2004)

- Eprints, Dspace, or Espace? (Oct 2004)

- "Life After NIH" (Apr 2005)

- A Keystroke Koan For Our Open Access Times (May 2005)

- "Disaggregated Journals" (Jul 2005)

SPARC has given the Australian Research Council the following advice:

SPARC has given the Australian Research Council the following advice: (SPARC's advice in boldface, followed in each case by my comment, indented, followed by Australian OA specialist Arthur Sale [AS] commenting on my comment, in italics, double-indented)SPARC: "Research funders should include in all grants and contracts a provision reserving for the government relevant non-exclusive rights (as described below) to research papers and data."

Fine, but this is not a prerequisite for self-archiving, nor for mandating self-archiving. It is enough if ARC clearly mandates deposit; the rest will take care of itself.SPARC: "All peer-reviewed research papers and associated data stemming from public funding should be required to be maintained in stable digital repositories that permit free, timely public access, interoperability with other resources on the Internet, and long-term preservation. Exemptions should be strictly limited and justified."AS: "A sensible fundee will take this action; how sensible they are will remain to be seen. The unsensible ones will have some explaining to do. ARC could have given advice like this, but didn't."

That, presumably, is what the ARC self-archiving mandate amounts to.SPARC: "Users should be permitted to read, print, search, link to, or crawl these research outputs. In addition, policies that make possible the download and manipulation of text and data by software tools should be considered."AS: "Exactly. And every university in Australia will have access to such a repository by end 2007. 50% already do."

All unnecessary; all comes with the territory, if self-archiving is mandated. (The policy does not need extra complications: a clear self-archiving mandate simply needs adoption and implementation.)SPARC: "Deposit of their works in qualified digital archives should be required of all funded investigators, extramural and intramural alike."AS: "Totally agree..."

Yes, the self-archiving mandate should apply to all funded research.SPARC: "While this responsibility might be delegated to a journal or other agent, to assure accountability the responsibility should ultimately be that of the funds recipient."AS: "It does."

Not clear what this refers to, but, yes, it is the fundee who should be mandated to self-archive.SPARC: "Public access to research outputs should be provided as early as possible after peer review and acceptance for publication. For research papers, this should be not later than six months after publication in a peer-reviewed journal. This embargo period represents a reasonable, adequate, and fair compromise between the public interest and the needs of journals."AS: "Yes the onus is on the fundee(s), and especially the principal investigator who has to submit the Final Report."

SPARC: "We also recommend that, as a means of further accelerating innovation, a portion of each grant be earmarked to cover the cost of publishing papers in peer-reviewed open-access journals, if authors so choose. This would provide potential readers with immediate access to results, rather than after an embargo period."The self-archiving mandate that ARC should adopt is the ID/OA mandate whereby deposit is mandatory immediately upon acceptance for publication, and the embargo (if any, 6 months max.) is applicable only to the date at which access to the deposit is set as Open Access (rather than Closed Access), not to the date of deposit itself. During any Closed Access embargo interval, each repository's semi-automatic EMAIL EPRINT REQUEST

button will cover all research usage needs.

AS: "ARC is silent on timing, but I expect a quick transition to the ID/OA policy by fundees. Anything else is a pain - it is easier to do this than run around like a headless chook later. The Research Quality Framework (RQF) will encourage instant mandate because of its citation metrics. NOTE ESPECIALLY THAT THE ARC GUIDELINES DO NOT SIT IN A VACUUM BY THEMSELVES. The National Health and Medical Research Council and the RQF are equally important. "

The ID/OA mandate -- together with the EMAIL EPRINT button -- already cover all immediate-access needs without needlessly diverting any research money at this time. The time to pay for publication will be if and when self-archiving causes subscriptions to collapse, and if that time ever comes, it will be the saved institutional subscription funds themselves that will pay for the publication costs, with no need to divert already-scarce funds from research. Instead to divert money from research now would be needlessly to double-pay for OA; OA can already be provided by author self-archiving without any further cost.Stevan HarnadAS: "This recommendation will certainly be disregarded, correctly in my opinion. ARC has never funded publication costs and does not intend to start now. Australian universities are already funded for publication and subscription costs through the normal block grants and research infrastructure funding. All they have to do is redirect some of their funding as they see fit. The recommendation might accelerate innovation, but it is not the ARC's job to fund innovation in the publishing industry."

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Saturday, December 16. 2006

Central versus Distributed Archives

On Fri, 15 Dec 2006, Heather Morrison wrote in the American Scientist Open Access Forum:

The year 2006 is hence not the one in which to fete this as "very healthy" growth -- unless we want to wait till doomsday to reach 100% OA.

At this rate, Ebs Hilf estimates that it would take till 2050 to reach 100% OA in Physics. And that is without mentioning that Arxiv-style central self-archiving has not yet caught on in any other field (except possibly economics) since 1991. In contrast, distributed self-archiving in, for example, computer science, has already long overtaken Arxiv-style central self-archiving. See Citeseer (a harvester of locally self-archived papers in computer science, already twice the size of Arxiv):

Logic alone should alert us that ever since Institutional IRs and Central CRs became completely equivalent and interoperable, and seamlessly harvestable and integrable, with the OAI protocol of 1999, the days of CRs were numbered.

It makes no sense for institutional researchers either to deposit only in a CR instead of their own IR, or to double-deposit (in their own IR plus CRs, such as PubMed Central). The direct deposits will be in the natural locus, the researcher's own IR. And then CRs will harvest, as Citeseer, OAister -- and, for that matter, Google and Google Scholar -- do.

OA self-archiving is meant to be done in the interests of the impact, visibility, and recording of each institution's research output. Institutional self-archiving tiles all of OA space (whereas CRs would have to criss-cross all disciplines, willy-nilly, redundantly, and arbitrarily).

Most important, institutions, being the primary research providers, have the most direct stake in maximising -- and the most direct means of monitoring -- the self-archiving of their own research output. Hence institutional self-archiving mandates -- reinforced by research funder self-archiving mandates -- will see to it that institutional research output is deposited in its natural, optimal locus: each institution's own IR (twinned and mirrored for redundancy and preservation). CRs (subject-based, multi-subject, national, or any other combination that might be judged useful) can then harvest from the distributed network of IRs.

American Scientist Open Access Forum

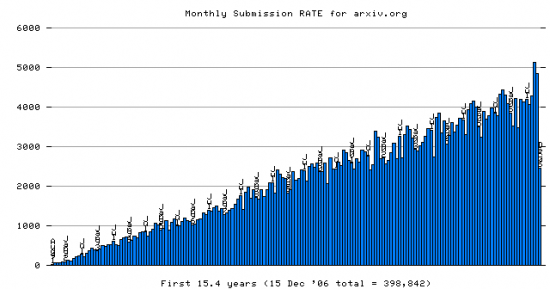

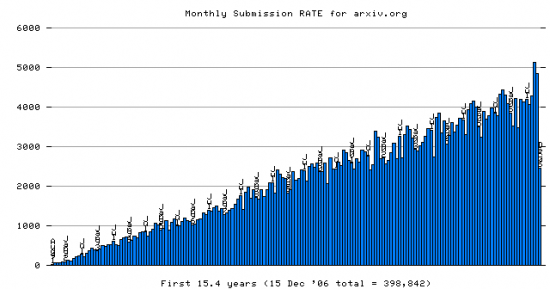

Arxiv has been showing this same, steady, unswerving linear increase in the number of deposits per month (quadratic acceleration of the total content) since the year 1991, and Arxiv has been tracking its own growth, monthly, since then.HM:"arXiv is showing very healthy growth, around 20% annually. I've been tracking arXiv on a quarterly basis, starting Dec. 31, 2005: [here]."

The year 2006 is hence not the one in which to fete this as "very healthy" growth -- unless we want to wait till doomsday to reach 100% OA.

At this rate, Ebs Hilf estimates that it would take till 2050 to reach 100% OA in Physics. And that is without mentioning that Arxiv-style central self-archiving has not yet caught on in any other field (except possibly economics) since 1991. In contrast, distributed self-archiving in, for example, computer science, has already long overtaken Arxiv-style central self-archiving. See Citeseer (a harvester of locally self-archived papers in computer science, already twice the size of Arxiv):

Logic alone should alert us that ever since Institutional IRs and Central CRs became completely equivalent and interoperable, and seamlessly harvestable and integrable, with the OAI protocol of 1999, the days of CRs were numbered.

It makes no sense for institutional researchers either to deposit only in a CR instead of their own IR, or to double-deposit (in their own IR plus CRs, such as PubMed Central). The direct deposits will be in the natural locus, the researcher's own IR. And then CRs will harvest, as Citeseer, OAister -- and, for that matter, Google and Google Scholar -- do.

OA self-archiving is meant to be done in the interests of the impact, visibility, and recording of each institution's research output. Institutional self-archiving tiles all of OA space (whereas CRs would have to criss-cross all disciplines, willy-nilly, redundantly, and arbitrarily).

Most important, institutions, being the primary research providers, have the most direct stake in maximising -- and the most direct means of monitoring -- the self-archiving of their own research output. Hence institutional self-archiving mandates -- reinforced by research funder self-archiving mandates -- will see to it that institutional research output is deposited in its natural, optimal locus: each institution's own IR (twinned and mirrored for redundancy and preservation). CRs (subject-based, multi-subject, national, or any other combination that might be judged useful) can then harvest from the distributed network of IRs.

- "Central vs. Distributed Archives" (began Jun 1999)Stevan Harnad

- "PubMed and self-archiving" (began Aug 2003)

- "Central versus institutional self-archiving" (began Nov 2003)

- "Harold Varmus: 'Self-Archiving is Not Open Access'" (began June 2006)

- Optimizing OA - Self-Archiving Mandates: What? Where? When? Why? How?

- Plugging the Loopholes in the Proposed FRPAA, RCUK and EU Self-Archiving Mandates

- Generic Rationale and Model for University Open Access Self-Archiving Mandate: Immediate-Deposit/Optional Access (ID/OA)

Swan, A., Needham, P., Probets, S., Muir, A., Oppenheim, C., O'Brien, A., Hardy, R., Rowland, F. and Brown, S. (2005) Developing a model for e-prints and open access journal content in UK further and higher education. Learned Publishing 18(1) pp. 25-40.ABSTRACT:A study carried out for the UK Joint Information Systems Committee examined models for the provision of access to material in institutional and subject-based archives and in open access journals. Their relative merits were considered, addressing not only technical concerns but also how e-print provision (by authors) can be achieved ? an essential factor for an effective e-print delivery service (for users). A "harvesting" model is recommended, where the metadata of articles deposited in distributed archives are harvested, stored and enhanced by a national service. This model has major advantages over the alternatives of a national centralized service or a completely decentralized one. Options for the implementation of a service based on the harvesting model are presented.

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Wednesday, December 13. 2006

Economies of Scale

In "Scale and scalability," Jan Velterop writes:

But individual authors making their own articles OA (green) by self-archiving them in their own Institutional Repositories, anarchically and distributedly, does not provide 100% of the contents of any individual journal, and its extent and growth rate is hard to ascertain. (In other words, individual mandates are just as anarchic as individual self-archiving with respect to the contents of any individual journal.)

Hence self-archiving is unlikely to cause journal cancellations until the self-archiving of all articles in all journals is reliably at or near 100%. If/when that happens, or is clearly approaching, journals can and will scale down to become peer-review service providers only, recovering their much reduced costs on the OA model that Jan favors. But journals are extremely unlikely to want to do that scaling down and conversion now, when there is no pressure to do it. And there is certainly no reason for researchers to sit waiting meanwhile, as they keep losing access, usage and impact. Mandates will pressure researchers to self-archive, and, eventually, 100% self-archiving might also pressure journals to scale down and convert to the model Jan advocates.

Right now, however, journals are all still making ends meet through subscriptions, whereas (non-self-archiving) researchers are all still losing about half their potential daily usage and impact, cumulatively. The immediate priority for research, researchers, their institutions and their funders is hence obvious, and it is certainly not to pay their journals' current asking-price for making each individual article OA, over and above paying for subscriptions: It is to make their own individual articles OA, right now, by self-archiving them, and to pay for peer review only if and when journals have minimized costs by scaling down to the essentials in the OA era if/when there is no longer any sustainable way of recovering those costs via subscriptions.

(By that time, of course, subscription cancellation savings will have become available to pay those reduced costs up-front. Today they are not; and double-paying up front would be pure folly.)

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

"self-archiving is... not scalable. As long as... only a small number of authors... [self-archive] anarchically and unpredictably, it will work... [But] [t]ake the anarchy and unpredictability out of it... via self-archiving mandates – and... [n]o publisher... could afford to allow authors to self-archive... and ‘green’ would fade out of existence."Individual journals making 100% of their own contents Open Access (OA) (gold), all at once, and all in one place, right now, is indeed likely to cause cancellations.

But individual authors making their own articles OA (green) by self-archiving them in their own Institutional Repositories, anarchically and distributedly, does not provide 100% of the contents of any individual journal, and its extent and growth rate is hard to ascertain. (In other words, individual mandates are just as anarchic as individual self-archiving with respect to the contents of any individual journal.)

Hence self-archiving is unlikely to cause journal cancellations until the self-archiving of all articles in all journals is reliably at or near 100%. If/when that happens, or is clearly approaching, journals can and will scale down to become peer-review service providers only, recovering their much reduced costs on the OA model that Jan favors. But journals are extremely unlikely to want to do that scaling down and conversion now, when there is no pressure to do it. And there is certainly no reason for researchers to sit waiting meanwhile, as they keep losing access, usage and impact. Mandates will pressure researchers to self-archive, and, eventually, 100% self-archiving might also pressure journals to scale down and convert to the model Jan advocates.

Right now, however, journals are all still making ends meet through subscriptions, whereas (non-self-archiving) researchers are all still losing about half their potential daily usage and impact, cumulatively. The immediate priority for research, researchers, their institutions and their funders is hence obvious, and it is certainly not to pay their journals' current asking-price for making each individual article OA, over and above paying for subscriptions: It is to make their own individual articles OA, right now, by self-archiving them, and to pay for peer review only if and when journals have minimized costs by scaling down to the essentials in the OA era if/when there is no longer any sustainable way of recovering those costs via subscriptions.

(By that time, of course, subscription cancellation savings will have become available to pay those reduced costs up-front. Today they are not; and double-paying up front would be pure folly.)

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Thursday, November 23. 2006

Research Journals Are Already Just Quality Controllers and Certifiers: So What Are "Overlay Journals"?

The notion of an "Overlay Journal" is and always has been somewhat inchoate -- potentially even incoherent, if construed in a way that conflates (1) access-provision with peer-review service-provision, (2) pre-peer-review preprints with peer-reviewed postprints (or posting with publishing), (3) archives (repositories) with journals, or (4) Central Archives/Repositories (CRs) in particular with distributed Institutional Repositories (IRs) in general.

SUMMARY: The notion of an "Overlay Journal" often unwittingly confuses (1) access-provision with peer-review service-provision, (2) pre-peer-review preprints with peer-reviewed postprints (or posting with publishing), (3) archives (repositories) with journals, or (4) Central Archives/Repositories (CRs) in particular with distributed Institutional Repositories (IRs) in general. Throughout the evolution of research communication -- from On-Paper to On-Line to Open Access -- peer review remains peer review, a journal remains a journal (i.e., a peer-review service-provider and certifier), and texts tagged as "published" by journal X remain texts tagged as published by journal X. All that changes is the access-medium and the degree of accessibility. (And possibly, one day, the cost-recovery model.)

(1) Access-Provision vs. Peer-Review Service-Provision. A research journal is and always has been both (i) an access-provider (producing, printing and distributing the print edition; producing and licensing the online edition) and (ii) a quality-control service-provider (implementing and certifying the peer review process -- but with the peers independent and refereeing for the journals for free). In the Open Access (OA) era, the access-provider functions of the research journal can and will be supplemented by author self-archiving of the final, revised, peer-reviewed postprint (in the author's own IR and/or a CR) in order to ensure that all would-be users have access, rather than only those whose institutions can afford access to the journal's subscription-based version.It is also possible -- but this is hypothetical and it is not yet known whether and when it will happen -- that the distributed network of IRs and CRs containing authors' self-archived postprints may eventually substitute for the traditional access-provision function of journals (i), at least insofar as online access is concerned. This does not mean that IRs and CRs become journals. It just means that the online access-provision function (i) is unbundled from the former double function of journals (i, ii), and offloaded onto the IR/CR network. And this is merely hypothetical at this time. Only the supplementary function is a reality today, not yet the substitute function. (Is this hypothetical outcome what is meant by "Overlay Journals"? If so, let's forget about them for now and work on reaching 100% OA self-archiving, crossing our "overlay" bridges only if/when we ever get to them.)

(2) Unrefereed Preprints vs. Refereed Postprints (Posting vs. Publishing). Authors self-archive both their pre-peer-review preprints and their peer-reviewed postprints in IRs and CRs, but the primary target of the OA movement, and of OA self-archiving mandates, is the peer-reviewed postprint (of all 2.5 million articles published annually in the planet's 24,000 peer-reviewed research journals). Self-archiving preprints (usually done in order to elicit informal peer feedback and to assert priority) is neither publication nor a substitute for publication. To post a preprint in an IR or CR is not to publish it; it is merely to provide access to it. In providing access to preprints, IRs and CRs are certainly not substituting for journals. (Preprints are not listed in academic CVs as "Publications" but as "Unpublished Manuscripts.")So what is an "Overlay Journal"? The idea arose (incoherently, almost like an Escher drawing of an impossible staircase) from the idea that journals could simply "overlay" their peer-review functions on the self-archived preprint. The idea was first mooted in connection with a CR (Arxiv), but it was never coherently spelled out.

(3) Archives (Repositories) vs. Journals. IRs and CRs are not themselves journals, nor even part-journals. They cannot and do not provide peer review, or certify its outcome. If an author's own IR were to try to do this, for its own research output, it would become an in-house vanity press, not a peer-reviewed journal. If a CR tried to do this, it would simply become a new journal start-up (competing with existing journals). Right now, IRs and CRs are merely access-providers -- providing access to both unpublished preprints and journal-published, -peer-reviewed, and -certified postprints.

(4) Central Archives/Repositories (CRs) vs. Distributed Institutional Repositories (IRs). CRs and IRs also differ in that CRs are few, and do not exist for all or most fields, whereas IRs are many and cover all fields. CRs are independent 3rd parties, not affiliated with, beholden to, or sharing common interests with the authors who deposit in them, whereas IRs are authors' own institutional showcases, sharing with their authors a joint interest in maximizing the visibility, usage, impact and prestige of their research findings. IRs are hence not eligible for undertaking the independent, neutral, 3rd-party quality-control function of journals. CRs, in contrast, are in principle eligible to become journals (just as any online entity today is), but if they do so, they do it in competition with the 24,000 existing journals, just as any new start-up journal does. Moreover, although CRs may already host preprints, those preprints are currently all destined for submission to established journals today; and those same CRs also host the postprints that result from the peer-review service provided by those journals. Hence CRs in no way substitute for that peer-review service-provision (ii) today.

(I will not be discussing here any of the speculations about "overlay" and "disaggregated" and "deconstructed" journals that are based on untested notions about scrapping peer review altogether, or replacing it with open peer commentary; nor will I be discussing far-fetched notions of "multiple-review/multiple-publication" (in which it is imagined that peer review is just a static accept/reject matter, like a connotea tag, and that papers can be multiply "published" by several different journals, taking no account of the fact that referees are already a scarce and over-used resource, nor of the fact that peer review depends on answerability and revision): These conjectures are all fine as possible supplements to peer review, but none has yet been shown to be a viable substitute for it. The notion of an "Overlay Journal" is accordingly only assessed here in the context of standard peer review, as it is practised today by virtually all of the 24,000 journals whose peer-reviewed content is the target of the OA movement.)

One rather trivial construal of "Overlay Journal" (not the intended interpretation) would be that instead of submitting preprints to journals, authors could deposit them in CRs (or IRs) and simply send the deposit's URL to the journal, to retrieve it from there, for peer-review. This would not make the journal an "Overlay" on the CR or IR; it would simply provide a more efficient means of submitting papers to journals (and this has indeed been adopted as an optional means of submission by several physics journals, just as the submission of digital drafts instead of hard copy, and submission via email instead of by mail has been quite naturally adopted, to speed and streamline submission and processing by most journals, in the digital era).

So submitting preprints to journals via IRs or CRs is not tantamount to making the IR or CR into an underlay for "Overlay Journals," nor to making journals into overlays for the IR or CR. (In the case of IRs, because the authorship of most journals is distributed across many institutions, depositing in IRs would have meant "Distributed-Overlay Journals" in any case, but let us not puzzle about what sort of an entity those might have been!)

What might be meant by an "Overlay Journal" in something other than this trivial optional-means-of-submission sense, then? Could the users of the term mean the hypothetical outcome contemplated earlier (1), with journals offloading their former access-provision function (i) onto the IR/CR network and downsizing to become just peer-review service-providers (ii)? Possibly, but at the moment journals don't seem to be inclined to do so, and if they did, it is likely that they would prefer to continue to be thought of as what they have always been: journals, with a name and an imprimatur. Paper journals were not "overlays" on libraries. Journals that abandon their print edition are still journals, not "overlays" on their electronic edition. If their electronic edition is jettisoned too, they're still journals, not "overlays" on IRs/CRs.

Once we recognise that access-provision (i) (whether on-paper or online) was always just an incidental, media-dependent function of peer-reviewed research journals, whereas peer-review service-provision and certification (ii) was always their essential function, then it becomes clear that -- medium-independently -- a journal was always just a peer-review service-provider and certifier of a paper's having successfully met its established quality standards: It has always provided a quality-control tag, -- the journal name -- affixed to a text, whether the text is on-paper on a bookshelf, in the journal's proprietary on-line archive, or in an OA IR or CR. In this very general sense, all journals already are (and always have been) "overlay journals": overlays over all these various media for storing and providing access to the papers resulting from having passed successfully through the journal's peer review procedure (which is not itself a static tagging exercise, but a dynamic, interactive, feedback-correction-and-revision process, answerable to the referees and editors).

In other words, throughout the evolution of research communication -- from On-Paper to On-Line to Open Access -- peer review remains peer review, a journal remains a journal (i.e., a peer-review service-provider and certifier), and texts tagged as "published" by "journal X" remain texts tagged as published by "journal X." All that changes is the access-medium and the degree of accessibility. (And possibly, one day, the cost-recovery model.)

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Thursday, January 19. 2006

Open Access is not about copyright abolition or author reprint royalties

[Update: See new definition of "Weak" and "Strong" OA, 29/4/2008]

Dr. Raveendran, whose message appears at the end of this item, is Chief Editor, Indian Journal of Pharmacology, an OA ["gold") Journal, but he seems to be mistaken about what Open Access (OA) means: He seems to think OA is about "abolishing copyright"! That is certainly not what OA means, or advocates. I am puzzled as to where that erroneous idea came from (and offer 3 hypotheses below), but first, the meaning of OA needs to be made clear straight away (I. DEFINITION OF OA, below).

Dr. Raveendran also recommends the journals pay author reprint royalties. I discuss this in the second part of this posting (II. AUTHOR REPRINT ROYALTIES?)

There are two ways to provide OA. One ("OA Green," also called BOAI-1) is for the author to publish the article in a traditional journal (with the usual copyright agreements) but also to make his own final draft freely accessible online by self-archiving it in on the web, free for all (usually in his own institutional repository).

Of the nearly 9000 journals published by the 128 publishers processed by SHERPA/Romeo so far (including virtually all of the top international journals), 93% have already endorsed author self-archiving.

The second way to provide OA ("OA Gold") is for the journal in which the article is published to make the published version freely accessible online. (Some, but not all, OA journals charge $500-$3000 per article to the author-institution for this service.) The total number of OA journals is currently 2000 (and Dr. Raveendra's IJP is one of them).

As should now be clear, neither form of OA involves the abolition of copyright. Both forms continue to depend on it. OA green retains conventional copyright or licensing agreements; OA gold sometimes adopts a Creative Commons copyright license, sometimes not.

The only three ways I can even imagine that Dr. Raveendran arrived at his mistaken idea that OA is about abolishing copyright are (1) from the minority of well-intentioned people who are unfamiliar with OA and have been (needlessly) urging researchers to retain copyright (or negotiate a Creative Commons License) rather than to transfer it to the journal in which they publish. There is nothing wrong with doing this, but it is neither OA nor necessary for OA (and implying that it is either OA or a necessary prerequisite of OA, is actually a disservice to OA, needlessly delaying it still longer, when it is already long overdue).

The second possibility is that Dr. Raveendran heard the recommendations (2) from an even tinier number of well-meaning but misinformed individuals who have been urging authors to make their work "public domain." e.g., the ill-fated US Sabo Bill (2003) . That 2003 Bill was not well thought out, and has already failed. It has been replaced in the US by the (pending) 2005 CURES Act, and in the UK by the UK Government Science and Technology Committee 2004 recommendation

which is soon (we hope) to be implemented as the 2006 RCUK self-archiving policy.

My third and last hypothesis as to how Dr. Raveendran might have arrived at his mistaken impression of OA is that it was somehow a result of some early, unfortunate internal squabbling in the OA movement about so-called "Free Access" (FA) vs. "Open Access" (OA).

That squabbling arose from two sources: the first was (i) an unnecessarily exacting initial "definition" of OA, defining it, needlessly, as not only the free online webwide access that it really is, but as also including the retention by the author of certain re-publishing/re-use rights, which the author then gives to all users.

This over-exacting initial definition of OA (since replaced in practice by the more natural, simpler, and more realistic one: "free online access") had itself been inspired by what had at first glance appeared to be valid analogies between the OA movement and (a) the Open Source Initiative, (b) the Creative Commons movement and (c) the data-sharing of the Human Genome Project.

Ultimately, however, all three analogies proved to be misleading and invalid, and the extra requirements they would have entailed (including author copyright retention/renegotiation and the granting of blanket re-use and re-publication rights to all users) proved to be both unnecessary and a retardant to OA, for the simple reason that for article texts (unlike software, data, and other kinds of content), all requisite and legitimate research uses already come with the territory when the full-texts are made immediately and permanently accessible for free for all online, webwide.

(The second source of the squabbling was (ii) a green/gold dispute about whether green OA is "true" OA. This has, I think, now been settled affirmatively, and so we can forget about it.)

Chief Editor

Indian Journal of Pharmacology

JIPMER, Pondicherry - 605 006

Ph: 0413-2271969

Stevan Harnad

Dr. Raveendran, whose message appears at the end of this item, is Chief Editor, Indian Journal of Pharmacology, an OA ["gold") Journal, but he seems to be mistaken about what Open Access (OA) means: He seems to think OA is about "abolishing copyright"! That is certainly not what OA means, or advocates. I am puzzled as to where that erroneous idea came from (and offer 3 hypotheses below), but first, the meaning of OA needs to be made clear straight away (I. DEFINITION OF OA, below).

Dr. Raveendran also recommends the journals pay author reprint royalties. I discuss this in the second part of this posting (II. AUTHOR REPRINT ROYALTIES?)

I. DEFINITION OF OAOA (Open Access) is about making the full-texts of all published, peer-reviewed research journal articles accessible online toll-free for all would-be users, webwide, in order to maximise their research usage and impact.

There are two ways to provide OA. One ("OA Green," also called BOAI-1) is for the author to publish the article in a traditional journal (with the usual copyright agreements) but also to make his own final draft freely accessible online by self-archiving it in on the web, free for all (usually in his own institutional repository).

Of the nearly 9000 journals published by the 128 publishers processed by SHERPA/Romeo so far (including virtually all of the top international journals), 93% have already endorsed author self-archiving.

The second way to provide OA ("OA Gold") is for the journal in which the article is published to make the published version freely accessible online. (Some, but not all, OA journals charge $500-$3000 per article to the author-institution for this service.) The total number of OA journals is currently 2000 (and Dr. Raveendra's IJP is one of them).

As should now be clear, neither form of OA involves the abolition of copyright. Both forms continue to depend on it. OA green retains conventional copyright or licensing agreements; OA gold sometimes adopts a Creative Commons copyright license, sometimes not.

The only three ways I can even imagine that Dr. Raveendran arrived at his mistaken idea that OA is about abolishing copyright are (1) from the minority of well-intentioned people who are unfamiliar with OA and have been (needlessly) urging researchers to retain copyright (or negotiate a Creative Commons License) rather than to transfer it to the journal in which they publish. There is nothing wrong with doing this, but it is neither OA nor necessary for OA (and implying that it is either OA or a necessary prerequisite of OA, is actually a disservice to OA, needlessly delaying it still longer, when it is already long overdue).

The second possibility is that Dr. Raveendran heard the recommendations (2) from an even tinier number of well-meaning but misinformed individuals who have been urging authors to make their work "public domain." e.g., the ill-fated US Sabo Bill (2003) . That 2003 Bill was not well thought out, and has already failed. It has been replaced in the US by the (pending) 2005 CURES Act, and in the UK by the UK Government Science and Technology Committee 2004 recommendation

which is soon (we hope) to be implemented as the 2006 RCUK self-archiving policy.

My third and last hypothesis as to how Dr. Raveendran might have arrived at his mistaken impression of OA is that it was somehow a result of some early, unfortunate internal squabbling in the OA movement about so-called "Free Access" (FA) vs. "Open Access" (OA).

That squabbling arose from two sources: the first was (i) an unnecessarily exacting initial "definition" of OA, defining it, needlessly, as not only the free online webwide access that it really is, but as also including the retention by the author of certain re-publishing/re-use rights, which the author then gives to all users.

This over-exacting initial definition of OA (since replaced in practice by the more natural, simpler, and more realistic one: "free online access") had itself been inspired by what had at first glance appeared to be valid analogies between the OA movement and (a) the Open Source Initiative, (b) the Creative Commons movement and (c) the data-sharing of the Human Genome Project.

Ultimately, however, all three analogies proved to be misleading and invalid, and the extra requirements they would have entailed (including author copyright retention/renegotiation and the granting of blanket re-use and re-publication rights to all users) proved to be both unnecessary and a retardant to OA, for the simple reason that for article texts (unlike software, data, and other kinds of content), all requisite and legitimate research uses already come with the territory when the full-texts are made immediately and permanently accessible for free for all online, webwide.

(The second source of the squabbling was (ii) a green/gold dispute about whether green OA is "true" OA. This has, I think, now been settled affirmatively, and so we can forget about it.)

"Free Access vs. Open Access" (2003)

"On the Deep Disanalogy Between Text and Software and Between Text and Data Insofar as Free/Open Access is Concerned"

"Apercus of WOS Meeting: Making Ends Meet in the Creative Commons" (2004)

"Open Access Does Not require Republishing and Reprinting Rights"

"Proposed update of BOAI definition of OA: Immediate and Permanent" (2005)

II. REPRINT ROYALTIES?The idea of peer-reviewed research journals offering to pay their authors "royalty" revenue from reprint sales is based on a misunderstanding of why researchers publish in peer-reviewed journals. It is in order to maximise the usage and impact of their findings, not in order to make pennies from their sales! (That is why researchers, as authors, give away their texts to their publishers as well as to all would-be users, and that is why researchers, as peer-reviewers, give away their refereeing services to publishers and authors for free.)

"Authors 'Victorious' in UnCover Copyright Suit" (2000)Indeed, in the paper era, authors used to take upon themselves the time and expense of providing free reprints to all would-be users who mailed them a reprint request (based, often, on scanning ISI's weekly "Current Contents") -- so eager were authors to maximise the usage and impact of their work. Today the OA movement's main motivation is to end all access-denial to would-be users who cannot afford the access-tolls, thereby ending authors' needless impact loss.

Harnad, S. (2006) Publish or Perish - Self-Archive to Flourish: The Green Route to Open Access. ERCIM News (January 2006)Indeed it was Thomas Walker's proposal that authors should pay journals for OA eprints (a precursor of OA gold) that launched the American Scientist Open Access Forum in 1998!

Maximising the Return on UK's Public Investment in Research

Maximising the Return on Australia's Public Investment in Research

Making the case for web-based self-archiving [Canada]

Walker, T.J. (1998) Free Internet Access to Traditional Journals. American Scientist 86(5)I doubt, though, that reinforcing access-blocking tolls is what Dr. Raveendra had in mind, given that his is an OA (gold) journal! If I might make a suggestion, a better use of any journal reprint-sale revenue would to be to use it to cover the journal's own costs, to ensure that it remains a viable OA journal in the long term! If there is a surplus, why not use it to reduce the journal's paper subscription costs, or reprint costs themselves, thereby increasing access still more, rather than simply offering the author a share in the access-blocking tolls?

R.Raveendran

From: R. Raveendran, Chief Editor, Indian Journal of Pharmacology

To: Discussion Group for Open Access Workshop India

Sent: Thursday, January 12, 2006 1:12 PM

Subject: [oa-india] Sharing reprint revenue, OA and FA

"I am not a great enthusiast of OA mainly because of its 'copyright abolition clause'. I have already expressed my concern on this forum that copyright abolition will benefit only the commercial organisations not the researchers and academics. In my opinion, Free Access will be more beneficial to researchers if only journals are willing to change their policies. One such policy and its benefits to the researchers is evident from the announcement given below. Journals can retain the copyright and use it to make money for themselves and the researchers. At the same time journals should not restrict any legitimate, non-commercial use of its contents by academics and researchers. Can't this be achieved by Free Access? Why do we need OA which is likely to kill many journals if not all?"IJP starts sharing reprint revenue with authors

Starting 2005, IJP took a policy decision, to reward authors for their contributions which bring in reprint revenue for the journal. Sale of reprints adds to the financial stability of the journal, while propagating knowledge transmitted by its contributors. Sharing of the reprint revenue by the journal is expected to motivate authors for better quality inputs to the IJP. This practice will be more rewarding for the journal as well as the authors

In 2005, IJP sold reprints for more than one lakh rupees. A German company, bought reprint rights of the paper "Ginger as an antiemetic in nausea and vomiting induced by chemotherapy: a randomized, crossover, double blind study " which was contributed by Smita Sontakke, Vijay Thawani and Meena Naik from Government Medical College, Nagpur (IJP, Feb 2003, 35: 32-36). The chief editor gave away 10% of the reprint revenue to the authors by presenting them with a cheque for Rs 12,000 during the Annual Conference of the IPS at Chennai in December 2005.

The IJP congratulates the first recipients of the "reprint share scheme" and hopes they would utilize this amount for academic pursuit.

Chief Editor

Indian Journal of Pharmacology

JIPMER, Pondicherry - 605 006

Ph: 0413-2271969

Stevan Harnad

Sunday, August 21. 2005

Open Letter to Research Councils UK: Rebuttal of ALPSP Critique

Professor Ian DiamondPoint-by-point rebuttal:

Chair, RCUK Executive Group

Research Councils UK Secretariat

Polaris House , North Star Ave

Swindon SN2 1ET

Date: 22 August

Dear Professor Diamond,

We are responding to the public letter, addressed to yourself, by Sally Morris (Executive Director of ALPSP, the Association of Learned and Professional Society Publishers), concerning the RCUK's proposed research self-archiving policy.

ALPSP says that the RCUK policy would have 'disastrous consequences' for journals, yet all objective evidence is precisely contrary to this dire prediction. In the point-by-point rebuttal attached (below) to this letter, we document this on the basis of the actual data and a careful logical analysis. Here is a summary:

ALPSP argues that a policy of mandated self-archiving of research articles in freely accessible repositories, when combined with the ready retrievability of those articles through search engines (such as Google Scholar) and interoperability (facilitated by standards such as OAI-PMH), "will accelerate the move to a disastrous scenario".

The disastrous scenario predicted by ALPSP is that an RCUK mandate would cause libraries to cancel subscriptions, which would in turn lead to the financial failure of scholarly journals, and so to the collapse of the quality control and peer review process that publishers manage.

Not only are these claims unsubstantiated, but all the evidence to date shows the reverse to be true: not only do journals thrive and co-exist alongside author self-archiving, but they can actually benefit from it -- both in terms of more citations and more subscriptions.

Moreover, there is a logical contradiction in the position adopted by ALPSP. On the one hand, ALPSP maintains that learned societies must be allowed to operate in a free market ("each publisher must have the right to establish the best way of expanding access to its journal content that is compatible with continuing viability"). Yet on the other hand, ALPSP is in effect asking RCUK to protect learned societies from the consequences of a free market -- specifically the right of those who have funded and produced research to make their product readily accessible for uptake by its intended users.

What no one denies is that today many researchers are unable to access all the research they need to do their work. As ALPSP itself acknowledges, researchers already have to make use of author self-archived articles in order to gain access to "otherwise inaccessible published articles," since no research institution can afford to subscribe to all the journals its researchers need.

In short, due to the current constraints on the accessibility of research results, the potential of British scholarship is not being maximised currently. Yet the constraints on accessibility can now, in the digital age, be eliminated completely, to the benefit of the UK economy and society, exactly in the way RCUK has proposed.

For this reason, we believe that RCUK should go ahead and implement its immediate-self-archiving mandate, without further delay. That done, RCUK can meet with ALPSP and other interested parties to discuss and plan how the UK Institutional Repositories can collaborate with journals and their publishers in sharing the newfound benefits of maximising UK research access and impact.

(A point-by-point rebuttal is attached below. A longer analysis, signed also by some non-UK supporters, is at http://www.ecs.soton.ac.uk/~harnad/Temp/alpsp.doc )

Yours faithfully,

Professor Tim Berners-Lee (University of Southampton)

Professor Dave De Roure (University of Southampton)

Professor Stevan Harnad (University of Southampton)

Professor Nigel Shadbolt (University of Southampton)

Professor Derek Law (University of Strathclyde)

Dr. Peter Murray-Rust (University of Cambridge)

Professor Charles Oppenheim (Loughborough University)

Professor Yorick Wilks (University of Sheffield)

ALPSP: a policy of mandated self-archiving of research articles in freely accessible repositories, when combined with the ready retrievability of those articles through search engines (such as Google Scholar) and interoperability (facilitated by standards such as OAI-PMH), will accelerate the move to a disastrous scenario.This hypothesis has already been tested and the actual evidence affords not the slightest hint of any 'move to a disastrous scenario.' Self-archiving is most advanced in physics, hence that is the strongest test of where it is moving: Since 1991, hundreds of thousands of articles have been made freely accessible and readily retrievable by physicists using the open archive called arXiv; those articles have been extensively accessed, retrieved, used and cited by other researchers -- exactly as their authors intended. Yet when asked, both of the large physics learned societies (the Institute of Physics Publishing in the UK and the American Physical Society) responded very explicitly that they cannot identify any loss of subscriptions to their journals as a result of this critical mass of self-archived and readily retrievable physics articles (footnote 1).

ALPSP: Librarians will increasingly find that 'good enough' versions of a significant proportion of articles in journals are freely available; in a situation where they lack the funds to purchase all the content their users want, it is inconceivable that they would not seek to save money by cancelling subscriptions to those journals. As a result, those journals will die.First, neither research topics nor research journals have national boundaries. RCUK-funded researchers publish articles in thousands of journals, and those articles represent the output of only a small fraction of the world's research population. It is therefore extremely unlikely that a 'significant proportion' of the articles in any particular journal will become freely available as a consequence of the RCUK policy.

Second, as we know, some physics journals already do contain a 'significant proportion' of articles that have been self-archived in the physics repository, arXiv -- yet librarians have not cancelled subscriptions: the journals continue to survive and thrive.

ALPSP: The consequences of the destruction of journals' viability are very serious. Not only will it become impossible to support the whole process of quality control, including (but not limited to) peer review, but in addition, the research community will lose all the other value and prestige which is added, for both author and reader, through inclusion in a highly rated journal with a clearly understood audience and rich online functionalityWherever authors and readers value the rich online functionality added by publishers they will still wish to have access to the journal, either through personal subscriptions or through their libraries. This is obviously the case for the physics journals. Publishers who add significant value create a product that users and their institutions will pay for.

Researchers who cannot access the journal version, however -- because their institutions 'lack the funds to purchase all the content their users want' -- should not be denied access to the basic research results, which have always been given away for free by their authors (to their publishers, as well as to all requesters of reprints). Nor should those authors be denied the usage and impact of those users. Such limitations on access have always hampered the impact and progress of British scholarship.

ALPSP: We absolutely reject unsupported assertions that self-archiving in publicly accessible repositories does not and will not damage journals. Indeed, we are accumulating a growing body of evidence that the opposite is the case, even at this early stage.And what is the evidence supporting the assertion that 'the opposite is the case' and journals are damaged? None. As we know, the Institute of Physics Publishing (like the American Physical Society) has already stated publicly that it cannot identify any loss of subscriptions as a result of 14 years of self-archiving by physicists (footnote 1). Moreover, institutional repository software developers are now working with publishers on ways to ensure that the usage of articles in repositories is credited to the publisher.

For example:

[1] Increasingly, librarians are making use of COUNTER-compliant (and therefore comparable) usage statistics to guide their decisions to renew or cancel journals. The Institute of Physics Publishing is therefore concerned to see that article downloads from its site are significantly lower for those journals whose content is substantially replicated in the ArXiV repository than for those which are not.

ALPSP: [2] Citation statistics and the resultant impact factors are of enormous importance to authors and their institutions; they also influence librarians' renewal/cancellation decisions. Both the Institute of Physics and the London Mathematical Society are therefore troubled to note an increasing tendency for authors to cite only the repository version of an article, without mentioning the journal in which it was later published.Librarians' decisions to cancel or subscribe to journals are made on the basis of a variety of measures, citation statistics being just one of them (footnote 2). But self-archiving increases citations, so journals carrying self-archived articles will perform better under this measure.

Citing the canonical version of an article wherever possible is a matter of author best-practice; it is misleading to cite momentary lags in scholarliness as if they were an argument against self-archiving. All of this can and will be quite easily and naturally adjusted, partly through updated scholarly practice and partly through institutional and publisher repositories collaborating in a system of pooled and shared citation statistics -- all credited to the official published version, as proper scholarliness dictates. These are all just natural adaptations to the new medium.

ALPSP: [3] Evidence is also growing that free availability of content has a very rapid negative effect on subscriptions. Oxford University Press made the contents of Nucleic Acids Research freely available online six months after publication; subscription loss was much greater than in related journals where the content was free after a year...In all three examples whole journals were made freely available, in their entirety, with all the added value and rich online functionality that a journal provides. This is not at all the same as the self-archiving of authors' drafts, which are simply the basic research results, provided by the author on a single-article basis. The latter, not the former, is the target of the proposed RCUK policy. It is hence highly misleading to cite the effects of the former as evidence of negative effects of the latter.

[4] The BMJ Publishing Group has noted a similar effect...

[5] In the USA, the Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences ... made freely available on the Web... noted a subscriptions decline