Quicksearch

Your search for kurtz returned 21 results:

Saturday, May 26. 2007

Craig et al.'s Review of Studies on the OA Citation Advantage

Update Jan 1, 2010: See Gargouri, Y; C Hajjem, V Larivière, Y Gingras, L Carr,T Brody & S Harnad (2010) “Open Access, Whether Self-Selected or Mandated, Increases Citation Impact, Especially for Higher Quality Research”

Update Feb 8, 2010: See also "Open Access: Self-Selected, Mandated & Random; Answers & Questions"

I've read Craig et al.'s critical review concerning the OA citation impact effect and will shortly write a short, mild review. But first here is Sally Morris's posting announcing Craig et al's review, on behalf of the Publishing Research Consortium (which "proposed" the review), followed by a commentary from Bruce Royan on diglib, a few remarks from me, then commentary by JWT Smith on jisc-repositories, followed by my response, and, last, a commentary by Bernd-Christoph Kaemper on SOAF, followed by my response.SUMMARY: The thrust of Craig et al.'s critical review (which was proposed by the Publishing Research Consortium and conducted by the staff of three publishers) is that despite the fact that virtually all studies comparing the citation counts for OA and non-OA articles keep finding the OA citation counts to be higher, it has not been proved beyond a reasonable doubt that the relationship is causal.

I agree: It is merely highly probable, not proved beyond a reasonable doubt. And I also agree that not one of the studies done so far is without some methodological flaw that could be corrected. But it is also highly probable that the results of the methodologically flawless versions of all those studies will be much the same as the results of the current studies. That's what happens when you have a robust major effect, detected by virtually every study, and only ad hoc methodological cavils and special pleading to rebut each of them with. Here is a common sense overview:

(1) Research quality is a necessary, but not a sufficient condition for citation impact: The research must also be accessible to be cited.

(2) Research accessibility is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for citation impact: The research must also be of sufficient quality to be cited.

(3) The OA impact effect is the finding that an article's citation counts are positively correlated with the probability that that article has been made OA: The more an article's citations, the more likely that that article has been made OA.

(4) That correlation has at least three (compatible) causal interpretations:

(4a) OA articles are more likely to be cited.

(4b) More-cited articles are more likely to be made OA.

(4c) A third factor makes it more likely that certain articles will be both more cited and made OA.

(5) Each of these causal interpretations is probably correct, and hence a contributor to the OA impact effect:

(5a) The better the article, the more likely it is to be cited, hence the more citations it gains if it is made more accessible (4a). (OA Article Quality Advantage, QA)

(5b) The better the article, the more likely it is to be made OA (4b). (OA Article Quality Bias, QB)

(5c) 10% of articles (and authors) receive 90% of citations. The authors of the better articles know they are better, and hence are more likely both to be cited and to make their articles OA, so as to maximize their visibility, accessibility and citations (4c). (OA Author QB and QA)

(6) In addition to QB and QA, there is an OA Early Access effect (EA): providing access earlier increases citations.

(7) The OA citation studies have not yet isolated and estimated the relative sizes of each of these (and other) contributing components. (OA also gives a Download Advantage (DA), and downloads are correlated with later citations; OA articles also have a Competitive Advantage (CA), but CA will vanish -- along with QB -- when all articles are OA).

(8) But the handwriting is on the wall as to the benefits of making articles OA, for those with eyes to see, and no conflicting interests to blind them.

Given all of this, here is a challenge for Craig et al: Instead of striving, like OJ Simpson's Dream Team, only to find flaws in the positive evidence for the OA impact differential, which is equally compatible with either interpretation (OA causes higher citations or higher citations cause OA) why don't Craig et al. do a simple study of their own? Since it is known that (in science) the top 10% of articles published receive 90% of the total citations made, why not test whether and to what extent the top 10% of articles published is over-represented among the c. 15% of articles that are being spontaneously made OA by their authors today? It is, after all, a logical possibility that all or most of the top 10% are already among the 15% that are being made OA: I think it's improbable; but it may repay Craig et al's effort to check whether it is so.

For if it did turn out that all or most of the top-cited 10% of articles are already among the c.15% of articles that are already being made OA, then reaching 100% OA would be far less urgent and important than I have been arguing, and OA mandates would likewise be less important. I for one would no longer find it important enough to archivangelize if I knew it was just for the bottom 90% of articles, the top 10% of articles having already been self-archived, spontaneously and sensibly, by their top 10% authors without having to be mandated. But it is Craig et al. who think this is closer to the truth, not me. So let them go out and demonstrate it.

Sally Morris (Publishing Research Consortium):Craig, Ian; Andrew Plume, Marie McVeigh, James Pringle & Mayur Amin (2007) Do Open Access Articles Have Greater Citation Impact? A critical review of the literature. Journal of Informetrics.A new, comprehensive review of recent bibliometric literature finds decreasing evidence for an effect of 'Open Access' on article citation rates. The review, now accepted for publication in the Journal of Informetrics, was proposed by the Publishing Research Consortium (PRC) and is available at its web site at www.publishingresearch.net. It traces the development of this issue from Steve Lawrence's original study in Nature in 2001 to the most recent work of Henk Moed and others.

Researchers have delved more deeply into such factors as 'selection bias' and 'early view' effects, and began to control more carefully for the effects of disciplinary differences and publication dates. As they have applied these more sophisticated techniques, the relationship between open access and citation, once thought to be almost self-evident, has almost disappeared.

Commenting on the paper, Lord May of Oxford, FRS, past president of the Royal Society, said 'In December 2005, the Royal Society called for an evidence-based approach to the scholarly communications debate. This excellent paper demonstrates that there is actually little evidence of a citation advantage for open access articles.'

The debate will certainly continue, and further studies will continue to refine current work. The PRC welcomes this discussion, and hopes that this latest paper may be a catalyst for a new round of informed scholarly exchange.

Sally Morris on behalf of the Publishing Research Consortium

It is notoriously tricky (at least since David Hume) to "prove" causality empirically. The thrust of the Craig et al. critique is that despite the fact that virtually all studies comparing the citation counts for OA and non-OA articles keep finding the OA citation counts to be higher, it has not been proven beyond a reasonable doubt that the relationship is causal.Bruce Royan wrote on diglib:

Sally claims that according to this article "the relationship between open access and citation, once thought to be almost self-evident, has almost disappeared."

Now I'm no Informetrician, but my reading of the article is that the authors reluctantly acknowledge that Open Access articles do have greater citation impact, but claim that this is less because they are Open Access per se, and more because:-they are available sooner than more conventionally published articles, orSally's point of view is understandable, since she is employed by a consortium of conventional publishers. It's interesting to note that the employers of the authors of this article are Wiley-Blackwell, Thomson Scientific, and Elsevier.

-they tend to be better articles, by more prestigious authors

Even more interesting is that, though this article has been accepted for publication in the conventional "Journal of Informetrics", a pdf of it (described as a summary, but there are 20 pages in JOI format, complete with diagrams, references etc) has already been mounted on the web for free download, in what might be mistaken for an example of green route open access.

Could this possibly be in order to improve the article's impact?

Professor Bruce Royan,

Concurrent Computing Limited.

I agree: It is merely highly probable, not proven beyond a reasonable doubt, that articles are more cited because they are OA, rather than OA merely because they are more cited (or both OA and more cited merely because of a third factor).

And I also agree that not one of the studies done so far is without some methodological flaw that could be corrected.

But it is also highly probable that the results of the methodologically flawless versions of all those studies will be much the same as the results of the current studies. That's what happens when you have a robust major effect, detected by virtually every study, and only ad hoc methodological cavils and special pleading to rebut each of them with.

But I am sure those methodological flaws will not be corrected by these authors, because -- OJ Simpson's "Dream Team" of Defense Attorneys comes to mind -- Craig et al's only interest is evidently in finding flaws and alternative explanations, not in finding out the truth -- if it goes against their client's interests...

Iain D.Craig: Wiley-BlackwellHere is a preview of my rebuttal. It is mostly just common sense, if one has no conflict of interest, hence no reason for special pleading and strained interpretations:

Andrew M.Plume, Mayur Amin: Elsevier

Marie E.McVeigh, James Pringle: Thomson Scientific

(1) Research quality is a necessary, but not a sufficient condition for citation impact: The research must also be accessible to be cited.

(2) Research accessibility is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for citation impact: The research must also be of sufficient quality to be cited.

(3) The OA impact effect is the finding that an article's citation counts are positively correlated with the probability that that article has been made OA: The more an article's citations, the more likely that that article has been made OA.

(4) This correlation has at least three causal interpretations that are not mutually exclusive:

(4a) OA articles are more likely to be cited.(5) Each of these causal interpretations is probably correct, and hence a contributor to the OA impact effect:

(4b) More-cited articles are more likely to be made OA.

(4c) A third factor makes it more likely that certain articles will be both more cited and made OA.

(5a) The better the article, the more likely it is to be cited, hence the more citations it gains if it is made more accessible (4a). (OA Article Quality Advantage, QA)(6) In addition to QB and QA, there is an OA Early Access effect (EA): providing access earlier increases citations.

(5b) The better the article, the more likely it is to be made OA (4b). (OA Article Quality Bias, QB)

(5c) 10% of articles (and authors) receive 90% of citations. The authors of the better articles know they are better, and hence are more likely both to be cited and to make their articles OA, so as to maximize their visibility, accessibility and citations (4c). (OA Author QB and QA)

(7) The OA citation studies have not yet isolated and estimated the relative sizes of each of these (and other) contributing components. (OA also gives a Download Advantage (DA), and downloads are correlated with later citations; OA articles also have a Competitive Advantage (CA), but CA will vanish -- along with QB -- when all articles are OA).

(8) But the handwriting is on the wall as to the benefits of making articles OA, for those with eyes to see, and no conflicting interests to blind them.

I do agree completely, however, with erstwhile (Princetonian and) Royal Society President Bob May's slightly belated call for "an evidence-based approach to the scholarly communications debate."

John Smith (JS) wrote in jisc-repositories:

I wonder if we can come at this discussion concerning the impact of OA on citation counts from another angle? Assuming we have a traditional academic article of interest to only a few specialists there is a simple upper bound to the number of citations it will have no matter how accessible it is.That is certainly true. It is also true that 10% of articles receive 90% of the citations. OA will not change that ratio, it will simply allow the usage and citations of those articles that were not used and cited because they could not be accessed to rise to what they would have been if they could have been used and cited.

JS: Also, the majority of specialist academics work in educational institutions where they have access to a wide range of paid for sources for their subject.OA is not for those articles and those users that already have paid access; it is for those that do not. No institution can afford paid access to all or most of the 2.5 million articles published yearly in the world's 24,000 peer-reviewed journals, and most institutions can only afford access to a small fraction of them.

OA is hence for that large fraction (the complement of the small fraction) of those articles that most users and most institutions cannot access. The 10% of that fraction that merit 90% of the citations today will benefit from OA the most, and in proportion to their merit. That increase in citations also corresponds to an increase in scholarly and scientific productivity and progress for everyone.

JS: Therefore any additional citations must mainly come from academics in smaller institutions that do not provide access to all relevant titles for their subject and/or institutions in the poorer countries of the world.It is correct that the additional citations will come from academics at the institutions that cannot afford paid access to the journals in which the cited articles appeared. It might be the case that the access denial is concentrated in the smaller institutions and the poorer countries, but no one knows to what extent that is true, and one can also ask whether it is relevant. For the OA problem is not just an access problem but an impact problem. And the research output of even the richest institutions is losing a large fraction of its potential research impact because it is inaccessible to the fraction to whom it is inaccessible, whether or not that missing fraction is mainly from the smaller, poorer institutions.

JS: Should it not be possible therefore to examine the citers to these OA articles where increased citation is claimed and show they include academics in smaller institutions or from poorer parts of the world?Yes, it is possible, and it would be a good idea to test the demography of access denial and OA impact gain. But, again, one wonders: Why would one assign this question of demographic detail a high priority at this time, when the access and impact loss have already been shown to be highly probable, when the remedy (mandated OA self-archiving) is at hand and already overdue, and when most of the skepticism about the details of the OA impact advantage comes from those who have a vested interest in delaying or deterring OA self-archiving mandates from being adopted?

(It is also true that a portion of the OA impact advantage is a competitive advantage that will disappear once all articles are OA. Again, one is inclined to reply: So what?)

This is not just an academic exercise but a call to action to remedy a remediable practical problem afflicting research and researchers.

JS: However, even if this were done and positive results found there is still another possible explanation. Items published in both paid for and free form are indexed in additional indexing services including free services like OAIster and CiteSeer. So it may be that it is not the availability per se that increases citation but the findability? Those who would have had access anyway have an improved chance of finding the article. Do we have proof that the additional citers accessed the OA version (assuming there is both an OA and paid for version)?Increased visibility and improved searching are always welcome, but that is not the OA problem. OAIster's usefulness is limited by the fact that it only contains the c. 15% of the literature that is being self-archived spontaneously (i.e., unmandated) today. Citeseer is a better niche search engine because computer scientists self-archive a much higher proportion of their research. But the obvious benchmark today is Google Scholar, which is increasingly covering all cited articles, whether OA or non-OA. It is in vain that Google Scholar enhances the visibility of non-OA articles for those would-be users to whom they are not accessible. Those users could already have accessed the metadata of those articles from online indices such as Web of Science or PubMed, only to reach a toll-access barrier when it came to accessing the inaccessible full-text corresponding to the visible metadata.

JS: It is possible that my queries above have already been answered. If so a reference to the work will suffice as a response.Accessibility is a necessary (but not a sufficient) condition for usage and impact. There is no risk that maximising accessibility will fail to maximise usage and impact. The only barrier between us and 100% OA is a few keystrokes.

I am a supporter of OA but also concerned that it is not falsely praised. If it is praised for some advantage and that advantage turns out not to be there it will weaken the position of OA proponents.

It is appalling that we continue to dither about this; it is analogous to dithering about putting on (or requiring) seat-belts until we have made sure that the beneficiaries are not just the small and the poor, and that seat-belts do not simply make drivers more safety-conscious.

JS: Even if the apparent citation advantage of OA turns out to be false it does not weaken the real advantages of OA. We should not be drawn into a time and effort wasting defence of it while there is other work to be done to promote OA.The real advantage of Open Access is Access. The advantage of Access is Usage and Impact (of which citations are one indicator). The Craig et al. study has not shown that the OA Impact Advantage is not real. It has simply pointed out that correlation does not entail causation. Duly noted. I agree that no time or effort should be spent now trying to demonstrate causation. The time and effort should be used to provide OA.

Bernd-Christoph Kaemper (B-CK) wrote on SOAF:I couldn't quite follow the logic of this posting. It seemed to be saying that, yes, there is evidence that OA increases impact, it is even trivially obvious, but, no, we cannot estimate how much, because there are possible confounding factors and the size of the increase varies.

Elsevier said that citation rates of their journals had gone up considerably because of the increased access through wide- spread online availability of their journals...

Online availability clearly increased the IF [journal citation impact factor]. In the FUTON subcategory, there was an IF gradient favoring journals with freely available articles. ..."

I think it is quite obvious why sources available with open access will be used and cited more often than others...

So the usefulness of open access is a matter of daily experience, not so much of academic discussions whether there is any empirical proof for a citation advantage of open access that may be isolated by eliminating all possible confounders...

That open access leads to more visibility and thereby potentially more citations is trivial, but this relative open access advantage will vary from journal to journal...

Due to the multitude of possible confounding factors I would not believe any of the figures calculated by Stevan Harnad as the cumulated lost impact, or conversely, the possible gain.

All studies have found that the size of the OA impact differential varies from field to field, journal to journal, and year to year. The range of variation is from +25% to over +250% percent. But the differential is always positive, and mostly quite sizeable. That is why I chose a conservative overall estimate of +50% for the potential gain in impact if it were not just the current 15% of research that was being made OA, but also the remaining 85%. (If you think 50% is not conservative enough, use the lower-bound 25%: You'll still find a substantial potential impact gain/loss. If you think self-selection accounts for half the gain, split it in half again: there's still plenty of gain, once you multiply by 85% of total citations.)

An interesting question that has since arisen (and could be answered by similar studies) is this:

It is a logical possibility that all or most of the top 10% are already among the 15% that are being made OA: I rather doubt it; but it would be worth checking whether it is so. [Attention lobbyists against OA mandates! Get out your scissors here and prepare to snip an out-of-context quote...]Since it is known that (in science) the top 10% of articles published receive 90% of the total citations made (Seglen 1992), to what extent is the top 10% of articles published over-represented among the c. 15% of articles that are being spontaneously made OA by their authors today?

[snip]The empirical studies of the relation between OA and impact have been mostly motivated by the objective of accelerating the growth of OA -- and thereby the growth of research usage and impact. Those who are oersuaded that the OA impact differential is merely or largely a non-causal self-selection bias are encouraged to demonstrate that that is the case.

If it did turn out that all or most of the top-cited 10% of articles are already among the c.15% of articles that are already being made OA, then reaching 100% OA would be far less urgent and important than I had argued, and OA mandates would likewise be less important. I for one would no longer find it important enough to archivangelize if I knew it was just for the bottom 90% of articles, the top 10% of articles having already been self-archived, spontaneously and sensibly, by their top 10% authors without having to be mandated.

[/snip]

Note very carefully, though, that the observed correlation between OA and citations takes the form of a correlation between the number of OA articles, relative to non-OA articles, at each citation level. The more highly cited an article, the more likely it is OA. This is true within journals, and within and across years, in every field tested.

And this correlation can arise because more-cited articles are more likely to be made OA or because articles that are made OA are more likely to be cited (or both -- which is what I think is in reality the case). It is certainly not the case that self-selection is the default or null hypothesis, and that those who interpret the effect as OA causing the citation increase hence have the burden of proof: The situation is completely symmetric numerically; so your choice between the two hypotheses is not based on the numbers, but on other considerations, such as prima facie plausibility -- or financial interest.

Until and unless it is shown empirically that today's OA 15% already contains all or most of the top-cited 10% (and hence 90% of what researchers cite), I think it is a much more plausible interpretation of the existing findings that OA is a cause of the increased usage and citations, rather than just a side-effect of them, and hence that there is usage and impact to be gained by providing and mandating OA. (I can quite understand why those who have a financial interest in its being otherwise [Craig et al. 2007] might prefer the other interpretation, but clearly prima facie plausibility cannot be their justification.)

I also think that 50% of total citations is a plausible overall estimate of the potential gain from OA, as long as it is understood clearly that that the 50% gain does not apply to every article made OA. Many articles are not found useful enough to cite no matter how accessible you make them. The 50% citation gain will mostly accrue to the top 10% of articles, as citations always do (though OA will no doubt also help to remedy some inequities and will sometimes help some neglected gems to be discovered and used more widely). In other words, the OA advantage to an article will be roughly proportional to that article's intrinsic citation value (independent of OA).

Other interesting questions: The top-cited articles are not evenly distributed among journals. The top journals tend to get the top-cited articles. It is also unlikely that journal subscriptions are evenly distributed among journals: The top journals are likely to be subscribed to more, and are hence more accessible.

So if someone is truly interested in these questions (as I am not!), they might calculate a "toll-accessibility index" (TAI) for each article, based on the number of researchers/institutions that have toll access to the journal in which that article is published. An analysis of covariance can then be done to see whether and how much the OA citation advantage is reduced if one controls for the article's TAI. (I suspect the answer will be: somewhat, but not much.)

B-CK: Could we do a thought experiment? From a representative group of authors, choose a sample of authors randomly and induce them to make their next article open access. Do you believe they will see as much gain in citations compared to their previous average citation levels as predicted from the various current "OA advantage" studies where several confounding factors are operating? Probably not - but what would remain of that advantage? -- I find that difficult to predict or model.From a random sample, I would expect an increase of around 50% or more in total citations, 90% of the increased citations going to the top 10%, as always.

B-CK: As I learned from your posting, you seem to predict that it will anyway depend on the previous citedness of the members of that group (if we take that as a proxy for the unknown actual intrinsic citation value of those articles), in the sense that more-cited authors will see a larger percentage increase effect.I don't think it's just a Matthew Effect; I think the highest quality papers get the most citations (90%), and the highest quality papers are apparently about 10% (in science, according to Seglen).

B-CK: To turn your argument around, most authors happily going open access in expectation of increased citation might be disappointed because the 50% increase will only apply to a small minority of them.That's true; but you could say the same for most authors going into research at all. There is no guarantee that they will produce the highest quality research, but I assume that researchers do what they do in the hope that they will, if not this time, then the next time, produce the highest quality research.

B-CK: That was the reason why I said that (as an individual author) I would rather not believe in any "promised" values for the possible gain.Where there is life, and effort, there is hope. I think every researcher should do research, and publish, and self-archive, with the ambition of doing the best quality work, and having it rewarded with valuable findings, which will be used and cited.

My "promise", by the way, was never that each individual author would get 50% more citations. (That would actually have been absurd, since over 50% of papers get no citations at all -- apart from self-citation -- and 50% of 0 is still 0.)

My promise, in calculating the impact gain/loss that you doubted, was to countries, research funders and institutions. On the assumption that the research output of each roughly covers the quality spectrum, they can expect their total citations to increase by 50% or more with OA, but that increase will be mostly at their high-quality end. (And the total increase is actually about 85% of 50%, as the baseline spontaneous self-archiving rate is about 15%.)

B-CK: That doesn't mean though that there are not enough other reasons to go for open access (I mentioned many of them in my posting).There are other reasons, but researchers' main motivation for conducting and publishing research is in order to make a contribution to knowledge that will be found useful by, and used by, and built upon by other researchers. There are pedagogic goals too, but I think they are secondary, and I certainly don't think they are strong enough to induce a researcher to make his publications OA, if the primary reason was not reason enough to induce them.

(Actually, I don't think any of the reasons are enough to induce enough researchers to provide OA, and that's why Green OA mandates are needed -- and being provided -- by researchers' institutions and funders.)

B-CK: With respect to the toll accessibility index, I completely agree. The occasional good article in an otherwise "obscure" journal probably has a lot to gain from open access, as many people would not bother to try to get hold of a copy should they find it among a lot of others in a bibliographic database search, if it doesn't look from the beginning like a "perfect match" of what they are looking for.You agree with the toll-accessibility argument prematurely: There are as yet no data on it, whereas there are plenty of data on the correlation between OA and impact.

B-CK: An interesting question to look at would also be the effect of open access on non-formal citation modes like web linking, especially social bookmarking. Clearly NPG is interested in Connotea also as a means to enhance the visibility of articles in their own toll access articles. Has anyone already tried such investigations?Although I cannot say how much it is due to other kinds of links or from citation links themselves, the University of Southampton, the first institution with a (departmental) Green OA self-archiving mandate, and also the one with the longest-standing mandate also has a surprisingly high webmetric, university-metric and G-factor rank:

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Bollen, J., Van de Sompel, H., Smith, J. and Luce, R. (2005) Toward alternative metrics of journal impact: A comparison of download and citation data. Information Processing and Management, 41(6): 1419-1440.

Brody, T., Harnad, S. and Carr, L. (2006) Earlier Web Usage Statistics as Predictors of Later Citation Impact. Journal of the American Association for Information Science and Technology (JASIST) 57(8) pp. 1060-1072.

Craig, Ian; Andrew Plume, Marie McVeigh, James Pringle & Mayur Amin (2007) Do Open Access Articles Have Greater Citation Impact? A critical review of the literature. Journal of Informetrics.

Davis, P. M. and Fromerth, M. J. (2007) Does the arXiv lead to higher citations and reduced publisher downloads for mathematics articles? Scientometrics 71: 203-215.

See critiques: 1 and 2.

Diamond, Jr. , A. M. (1986) What is a Citation Worth? Journal of Human Resources 21:200-15, 1986,

Eysenbach, G. (2006) Citation Advantage of Open Access Articles. PLoS Biology 4: 157.

Hajjem, C., Harnad, S. and Gingras, Y. (2005) Ten-Year Cross-Disciplinary Comparison of the Growth of Open Access and How it Increases Research Citation Impact. IEEE Data Engineering Bulletin 28(4) pp. 39-47.

Hajjem, C. and Harnad, S. (2006) Manual Evaluation of Robot Performance in Identifying Open Access Articles. Technical Report, Institut des sciences cognitives, Universite du Quebec a Montreal.

Hajjem, C. and Harnad, S. (2006) The Self-Archiving Impact Advantage: Quality Advantage or Quality Bias? Technical Report, ECS, University of Southampton.

Hajjem, C. and Harnad, S. (2007) Citation Advantage For OA Self-Archiving Is Independent of Journal Impact Factor, Article Age, and Number of Co-Authors. Technical Report, Electronics and Computer Science, University of Southampton.

Hajjem, C. and Harnad, S. (2007) The Open Access Citation Advantage: Quality Advantage Or Quality Bias? Technical Report, Electronics and Computer Science, University of Southampton.

Harnad, S. & Brody, T. (2004) Comparing the Impact of Open Access (OA) vs. Non-OA Articles in the Same Journals, D-Lib Magazine 10 (6) June

Harnad, S. (2005) Making the case for web-based self-archiving. Research Money 19(16).

Harnad, S. (2005) Maximising the Return on UK's Public Investment in Research. (Unpublished ms.)

Harnad, S. (2005) OA Impact Advantage = EA + (AA) + (QB) + QA + (CA) + UA. (Unpublished ms.)

Harnad, S. (2005) On Maximizing Journal Article Access, Usage and Impact. Haworth Press (occasional column).

Harnad, S. (2006) Within-Journal Demonstrations of the Open-Access Impact Advantage: PLoS, Pipe-Dreams and Peccadillos (LETTER). PLOS Biology 4(5).

Henneken, E. A., Kurtz, M. J., Eichhorn, G., Accomazzi, A., Grant, C., Thompson, D., and Murray, S. S. (2006) Effect of E-printing on Citation Rates in Astronomy and Physics. Journal of Electronic Publishing, Vol. 9, No. 2, Summer 2006

Henneken, E. A., Kurtz, M. J., Warner, S., Ginsparg, P., Eichhorn, G., Accomazzi, A., Grant, C. S., Thompson, D., Bohlen, E. and Murray, S. S. (2006) E-prints and Journal Articles in Astronomy: a Productive Co-existence Learned Publishing.

Kurtz, M. J., Eichhorn, G., Accomazzi, A., Grant, C. S., Demleitner, M., Murray, S. S. (2005) The Effect of Use and Access on Citations. Information Processing and Management, 41 (6): 1395-1402.

Kurtz, Michael and Brody, Tim (2006) The impact loss to authors and research. In, Jacobs, Neil (ed.) Open Access: Key strategic, technical and economic aspects. Oxford, UK, Chandos Publishing.

Lawrence, S, (2001) Online or Invisible?, Nature 411 (2001) (6837): 521.

Metcalfe, Travis S (2006) The Citation Impact of Digital Preprint Archives for Solar Physics Papers. Solar Physics 239: 549-553

Moed, H. F. (2006) The effect of 'Open Access' upon citation impact: An analysis of ArXiv's Condensed Matter Section (preprint)

Perneger, T. V. (2004) Relation between online 'hit counts' and subsequent citations: prospective study of research papers in the British Medical Journal. British Medical Journal 329:546-547.

Seglen, P.O. (1992) The skewness of science. The American Society for Information Science 43: 628-638

Thursday, March 15. 2007

Don't Count Your (Golden) Chickens Before Your (Green) Eggs Are Laid

SUMMARY: Michael Kurtz writes:

Research is growing. (True, but that is independent of OA.)

Publication costs are not a large percentage of total research costs. (True, but publication costs are already being paid in full, today, by subscription fees; any new publication charges today hence mean additional funds redirected from research -- or from elsewhere -- to double-pay, unless the existing subscription fees are redirected toward paying the publication charges.)

OA enhances research progress. (True)

Author publication charges are not new (in some fields). (True, but new OA publication charges, today, would be new, and additional, unless their payment was redirected from subscription savings.)

Mandated Green OA could cause subscription collapse. (Possibly, but if it did, that would simultaneously release the subscription savings to be redirected to pay for Gold OA publication charges [probably reduced to just the cost of peer review]; and meanwhile we would already have 100% [Green] OA, either way.)

In some fields, Central Repositories (CRs) like Arxiv have a larger Green OA percentage of total research output than Institutional Repositories (IRs). (A few fields do provide Green OA, unmandated, today, but most don't; that's why we need mandates; IRs that mandate Green reach 100% OA within about two years; institutions and funders mandate; "fields" do not; institutions wish to record, showcase, and maximize the impact of their own research output; "fields" do not; CRs can harvest from IRs; the locus of deposit for mandates should be researchers' own IRs.)

I would dearly love to adhere to my dictum "Hypotheses non Fingo," but with hypotheses being finged willy-nilly by others -- at the cost of neglecting or even discouraging tried-and-tested practical (and a-theoretical) action (i.e., Green OA mandates) -- I am left with little choice but to resort to counter-hypothesizing:

On Wed, 14 Mar 2007, Michael Kurtz [MK] wrote in the American Scientist Open Access Forum:

MK: "(A) THE CURRENT SITUATION. The quantity of scientific research has been increasing exponentially for several generations. This increase, roughly an order of magnitude during my lifetime (~4% per year, essentially the same as the growth in the global economy), has been mediated and enabled by the existing system for scientific communication, namely toll access journals and libraries."Correct.

And another thing has happened in the past generation or so: The birth of the Net and Web, making it possible to supplement toll-access with author-provided free online access (Green OA).

That development has next to nothing to do with the growth in the number of articles, nor with the price of journals. It has to do with the possibility of supplementing toll access with free online access.

MK: "(B) THE CURRENT COSTS. Direct costs for journals are remarkably small, about 1% of the total research and development budget (1). This compares with other costs involved such as (2) unpaid refereeing and editing 1% and the non-acquisition costs of a library, 2%. Possible changes to the direct cost of journals, up or down, are likely to be smaller than the error in estimating the yearly inflation adjustments."Correct, but irrelevant to the question of providing free online access for would-be users who cannot afford toll access.

Yes, if the money currently being spent on user-institution access-tolls were instead redirected to pay for author-institution publication charges, no more or less money would be spent, and online access would be free (Gold OA). But that is happening far too slowly, and does not depend only on the researcher community. Supplementing toll access with free online access (Green OA) is entirely in the hands of the research community.

Providing supplementary online access for free can be accelerated to 100% within a year or two through the adoption of research funder and university Green OA self-archiving mandates. That too is in the hands of the research community. Until it is done, research usage and impact continues to be lost, needlessly, daily.

MK: "(C) THE POSSIBLE BENEFIT OF OPEN ACCESS. The purpose of OA is to increase the amount and quality of research. The growth rate of research is currently ~4%; if OA is a massive success, it could perhaps increase this growth rate by 10%, which would be a yearly increment of 0.4% of total research. It may be expected that the greatest effect of OA would be in cross-disciplinary research, such as Nanotechnology."(The quantitative estimates are still rather speculative. [Here are some more.] But let us agree that providing OA will indeed increase research productivity and progress.)

MK: "(D) THE RISK OF OPEN ACCESS. By substantially changing the economics of journal publishing OA risks the catastrophic financial collapse of some publishers. This is especially true for the mandated 100% green OA path."If and when mandated 100% Green OA does cause subscriptions to be cancelled to unsustainable levels, the resultant user-institution subscription savings can be redirected to pay instead for author-institution publication charges (Gold OA).

Green OA mandates, by research institutions and funders are possible (indeed actual), and can grow institution by institution and funder by funder.

If Gold OA (with its attendant redirection of subscription funds) can be mandated at all, it certainly cannot be done institution by institution and funder by funder (with 24,000 journals, 10,000 institutions, and hundreds of public funders worldwide). Redirection, if it is to occur at all, has to be driven by Green OA mandates.

Pre-emptive redirection of funds (by an institution or a funder) toward Gold OA, without being preceded by 100% Green OA, is a waste of money, effort and time, today. (After 100% Green OA it is fine, as long as there is no double-paying, through redirection of research money instead of subscription money.)

MK: "(E) CURRENT GREEN MODELS. There are basically two types of Green repository: centralized, such as arXiv, and distributed, as the institutional repositories. Only arXiv has much of a track record. After more than 15 years arXiv only has more than half the refereed articles in the two subfields of High Energy Physics and Astrophysics; only HEP has more than 90%. It does not appear that there is any subfield of science where the existing institutional repositories contain more than half of the refereed literature."It is completely irrelevant where the free online articles are located. (The IRs and CRs are all OAI-interoperable.) What matters is that 100% of articles should be free online. Spontaneous central archiving has not reached 100% in 15 years (where it is being done at all). The natural and optimal place for institutions to mandate the deposit of their own article output is in their own IRs. That covers all of research output space. Mandated IRs fill within two years. Research funder mandates should reinforce the institutional mandates. If CRs are desired, they can harvest from the IRs.

MK: "(F) CURRENT GOLD MODELS. Page charges have existed for decades as a method of financing journals; while their use has been in decline for some time several venerable titles use them, in whole or in part, and there are several new, page charge funded, OA journals. Direct subsidies, by scholarly organizations and funding agencies, have long been used to support scientific publishing. Nearly all technical reports series are funded in this manner."Publication charges are currently being fully covered by subscriptions, but access is not open to all would-be users, hence research usage and impact (productivity and progress) are being needlessly lost.

There is no realistic way (nor is there a will) to redirect the subscription money currently being spent by 10,000 user-institutions worldwide for various subsets of 24,000 journals toward instead paying author-institution Gold OA publication charges. Hence the only money that can be redirected to pay for Gold OA today (by institutions or funders) is money that is currently being spent on research or other expenses, thereby effectively double-paying for publication (and at a time when subscription costs are already inflated).

Hence if the goal is 100% OA, the way to reach it is through institutions and funders mandating Green OA.

After that, redirect toward Gold OA to your heart's content. But to do so before that, or instead of that, is pure folly.

P.S. The journal affordability problem and the research accessibility problem are not the same problem. Green OA mandates will solve the research accessibility problem for sure. They may or may not cause unsustainable cancellations, but either way they will ease, though not solve, the journal affordability problem (by making the decision about which journal subscriptions to purchase from a limited serials budget into less of a life-or-death question, given that 100% Green OA is there as a safety net for accessing whatever an institutions cannot afford). Green OA, if it causes cancellations, will also cause cost-cutting and downsizing (the IRs can take over the access-provision and archiving load, leaving the journals with peer-review management as their only service), making (post-Green) Gold OA more affordable than it would be today (pre-Green).

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Sunday, January 21. 2007

The Open Access Citation Advantage: Quality Advantage Or Quality Bias?

Update Jan 1, 2010: See Gargouri, Y; C Hajjem, V Larivière, Y Gingras, L Carr,T Brody & S Harnad (2010) “Open Access, Whether Self-Selected or Mandated, Increases Citation Impact, Especially for Higher Quality Research”

Update Feb 8, 2010: See also "Open Access: Self-Selected, Mandated & Random; Answers & Questions"

This is a preview of some preliminary data (not yet refereed), collected by my doctoral student at UQaM, Chawki Hajjem. This study was done in part by way of response to Henk Moed's replies to my comments on Moed's (self-archived) preprint:

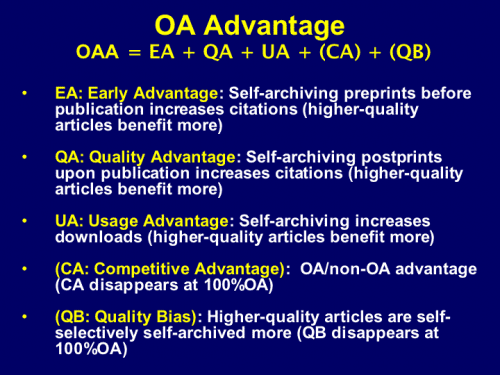

SUMMARY: Many studies have now reported the positive correlation between Open Access (OA) self-archiving and citation counts ("OA Advantage," OAA). But does this OAA occur because articles that are self-archived are more likely to be cited ("Quality Advantage": QA) or because articles that are more likely to be cited are more likely to be self-archived ("Quality Bias," QB)? The probable answer is both. Three studies [by Kurtz and co-workers in astrophysics, Moed in condensed matter physics, and Davis & Fromerth in mathematics] had attributed the OAA to QB [and to EA, the Early Advantage of self-archiving the preprint before publication] rather than QA. These three fields, however, happen to be among the minority of fields that (1) make heavy use of prepublication preprints and (2) have less of a postprint access problem than most other fields. Chawki Hajjem has now analyzed preliminary evidence based on over 100,000 articles from multiple fields, comparing self-selected self-archiving with mandated self-archiving to estimate the contributions of QB and QA to the OAA. Both factors contribute, and the contribution of QA is greater.

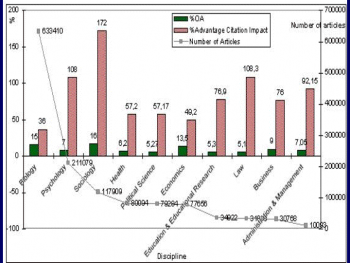

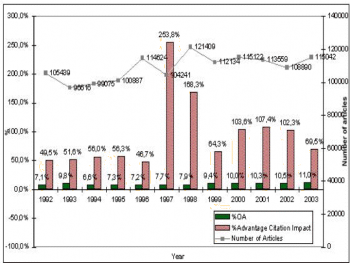

Moed, H. F. (2006) The effect of 'Open Access' upon citation impact: An analysis of ArXiv's Condensed Matter SectionMoed's study is about the "Open Access Advantage" (OAA) -- the higher citation counts of self-archived articles -- observable across disciplines as well as across years as in the following graphs from Hajjem et al. 2005 (red bars are the OAA):

The focus of the present discussion is the factors underlying the OAA. There are at least five potential contributing factors, but only three of them are under consideration here: (1) Early Advantage (EA), (2) Quality Advantage (QA) and (3) Quality Bias (QB -- also called "Self-Selection Bias").FIGURE 1. Open Access Citation Advantage By Discipline and By Year.

Green bars are percentage of articles self-archived (%OA); red bars, percentage citation advantage (%OAA) for self-archived articles for 10 disciplines (upper chart) across 12 years (lower chart, 1992-2003). Gray curve indicates total articles by discipline and year.

Source: Hajjem, C., Harnad, S. and Gingras, Y. (2005) Ten-Year Cross-Disciplinary Comparison of the Growth of Open Access and How it Increases Research Citation Impact. IEEE Data Engineering Bulletin 28(4) pp. 39-47.

Preprints that are self-archived before publication have an Early Advantage (EA): they get read, used and cited earlier. This is uncontested.

Kurtz, Michael and Brody, Tim (2006) The impact loss to authors and research. In, Jacobs, Neil (ed.) Open Access: Key strategic, technical and economic aspects. Oxford, UK, Chandos Publishing.In addition, the proportion of articles self-archived at or after publication is higher in the higher "citation brackets": the more highly cited articles are also more likely to be the self-archived articles.

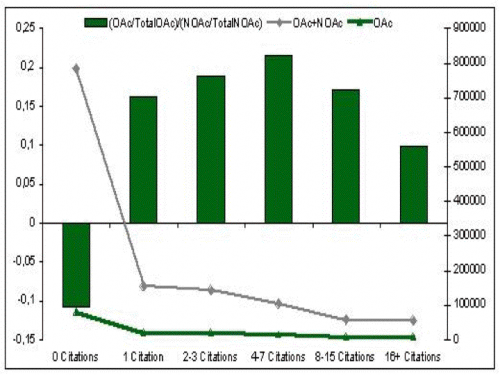

The question, then, is about causality: Are self-archived articles more likely to be cited because they are self-archived (QA)? Or are articles more likely to be self-archived because they are more likely to be cited (QB)?FIGURE 2. Correlation between Citedness and Ratio of Open Access (OA) to Non-Open Access (NOA) Ratios.

The (OAc/TotalOAc)/(NOAc/TotalNOAc) ratio (across all disciplines and years) increases as citation count (c) increases (r = .98, N=6, p<.005). The more cited an article, the more likely that it is OA. (Hajjem et al. 2005)

The most likely answer is that both factors, QA and QB, contribute to the OAA: the higher quality papers gain more from being made more accessible (QA: indeed the top 10% of articles tend to get 90% of the citations). But the higher quality papers are also more likely to be self-archived (QB).

As we will see, however, the evidence to date, because it has been based exclusively on self-selected (voluntary) self-archiving, is equally compatible with (i) an exclusive QA interpretation, (ii) an exclusive QB interpretation or (iii) the joint explanation that is probably the correct one.

The only way to estimate the independent contributions of QA and QB is to compare the OAA for self-selected (voluntary) self-archiving with the OAA for imposed (obligatory) self-archiving. We report some preliminary results for this comparison here, based on the (still small sample of) Institutional Repositories that already have self-archiving mandates (chiefly CERN, U. Southampton, QUT, U. Minho, and U. Tasmania).

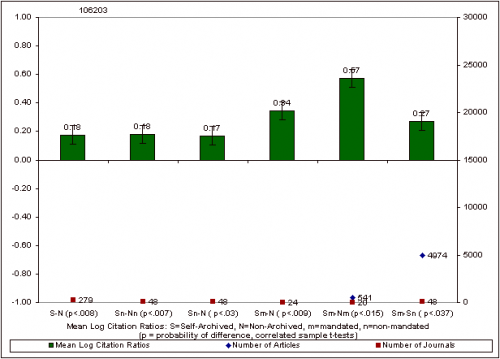

FIGURE 3. Self-Selected Self-Archiving vs. Mandated Self-Archiving: Within-Journal Citation Ratios (for 2004, all fields).

S = citation counts for articles self-archived at institutions with (Sm) and without (Sn) a self-archiving mandate. N = citation counts for non-archived articles at institutions with (Nm) and without (Nn) mandate (i.e., Nm = articles not yet compliant with mandate). Grand average of (log) S/N ratios (106,203 articles; 279 journals) is the OA advantage (18%); this is about the same as for Sn/Nn (27972 articles, 48 journals, 18%) and Sn/N (17%); ratio is higher for Sm/N (34%), higher still for Sm/Nm (57%, 541 articles, 20 journals); and Sm/Sn = 27%, so self-selected self-archiving does not yield more citations than mandated; rather the reverse. (All six within-pair differences are significant: correlated sample t-tests.) (NB: preliminary, unrefereed results.)

Summary: These preliminary results suggest that both QA and QB contribute to OAA, and that the contribution of QA is greater than that of QB.

Discussion: On Fri, 8 Dec 2006, Henk Moed [HM] wrote:

HM: "Below follow some replies to your comments on my preprint 'The effect of 'Open Access' upon citation impact: An analysis of ArXiv's Condensed Matter Section'...The findings are definitely consistent for Astronomy and for Condensed Matter Physics. In both cases, most of the observed OAA came from the self-archiving of preprints before publication (EA).

"1. Early view effect. [EA] In my case study on 6 journals in the field of condensed matter physics, I concluded that the observed differences between the citation age distributions of deposited and non-deposited ArXiv papers can to a large extent - though not fully - be explained by the publication delay of about six months of non-deposited articles compared to papers deposited in ArXiv. This outcome provides evidence for an early view [EA] effect upon citation impact rates, and consequently upon ArXiv citation impact differentials (CID, my term) or Arxiv Advantage (AA, your term)."SH: "The basic question is this: Once the AA (Arxiv Advantage) has been adjusted for the "head-start" component of the EA (by comparing articles of equal age -- the age of Arxived articles being based on the date of deposit of the preprint rather than the date of publication of the postprint), how big is that adjusted AA, at each article age? For that is the AA without any head-start. Kurtz never thought the EA component was merely a head start, however, for the AA persists and keeps growing, and is present in cumulative citation counts for articles at every age since Arxiving began".HM: "Figure 2 in the interesting paper by Kurtz et al. (IPM, v. 41, p. 1395-1402, 2005) does indeed show an increase in the very short term average citation impact (my terminology; citations were counted during the first 5 months after publication date) of papers as a function of their publication date as from 1996. My interpretation of this figure is that it clearly shows that the principal component of the early view effect is the head-start: it reveals that the share of astronomy papers deposited in ArXiv (and other preprint servers) increased over time. More and more papers became available at the date of their submission to a journal, rather than on their formal publication date. I therefore conclude that their findings for astronomy are fully consistent with my outcomes for journals in the field of condensed matter physics."

Moreover, in Astronomy there is already 100% "OA" to all articles after publication, and this has been the case for years now (for the reasons Michael Kurtz and Peter Boyce have pointed out: all research-active astronomers have licensed access as well as free ADS access to all of the closed circle of core Astronomy journals: otherwise they simply cannot be research-active). This means that there is only room for EA in Astronomy's OAA. And that means that in Astronomy all the questions about QA vs QB (self-selection bias) apply only to the self-archiving of prepublication preprints, not to postpublication postprints, which are all effectively "OA."

To a lesser extent, something similar is true in Condensed-Matter Physics (CondMP): In general, research-active physicists have better access to their required journals via online licensing than other fields do (though one does wonder about the "non-research-active" physicists, and what they could/would do if they too had OA!). And CondMP too is a preprint self-archiving field, with most of the OAA differential again concentrated on the prepublication preprints (EA). Moreover, Moed's test for whether or not a paper was self-archived was based entirely on its presence/absence in ArXiv (as opposed to elsewhere on the Web, e.g., on the author's website or in the author's Institutional Repository).

Hence Astronomy and CondMP are fields that are "biassed" toward EA effects. It is not surprising, therefore, that the lion's share of the OAA turns out to be EA in these fields. It also means that the remaining variance available for testing QA vs. QB in these fields is much narrower than in fields that do not self-archive preprints only, or mostly.

Hence there is no disagreement (or surprise) about the fact that most of the OAA in Astronomy and CondMP is due to EA. (Less so in the slower-moving field of maths; see: "Early Citation Advantage?.")

I agree with all this: The probable quality of the article was estimated from the probable quality of the author, based on citations for non-OA articles. Now, although this correlation, too, goes both ways (are authors' non-OA articles more cited because their authors self-archive more or do they self-archive more because they are more cited?), I do agree that the correlation between self-archiving-counts and citation-counts for non-self-archived articles by the same author is more likely to be a QB effect. The question then, of course, is: What proportion of the OAA does this component account for?SH: "The fact that highly-cited articles (Kurtz) and articles by highly-cited authors (Moed) are more likely to be Arxived certainly does not settle the question of cause and effect: It is just as likely that better articles benefit more from Arxiving (QA) as that better authors/articles tend to Arxive/be-Arxived more (QB)."HM: "2. Quality bias. I am fully aware that in this research context one cannot assess whether authors publish [sic] their better papers in the ArXiv merely on the basis of comparing citation rates of archived and non-archived papers, and I mention this in my paper. Citation rates may be influenced both by the 'quality' of the papers and by the access modality (deposited versus non-deposited). This is why I estimated author prominence on the basis of the citation impact of their non-archived articles only. But even then I found evidence that prominent, influential authors (in the above sense) are overrepresented in papers deposited in ArXiv."

HM: "But I did more that that. I calculated Arxiv Citation Impact Differentials (CID, my term, or ArXiv Advantage, AA, your term) at the level of individual authors. Next, I calculated the median CID over authors publishing in a journal. How then do you explain my empirical finding that for some authors the citation impact differential (CID) or ArXiv Advantage is positive, for others it is negative, while the median CID over authors does not significantly differ from zero (according to a Sign test) for all journals studied in detail except Physical Review B, for which it is only 5 per cent? If there is a genuine 'OA advantage' at stake, why then does it for instance not lead to a significantly positive median CID over authors? Therefore, my conclusion is that, controlling for quality bias and early view effect, in the sample of 6 journals analysed in detail in my study, there is no sign of a general 'open access advantage' of papers deposited in ArXiv's Condensed Matter Section."My interpretation is that EA is the largest contributor to the OAA in this preprint-intensive field (i.e., most of the OAA comes from the prepublication component) and that there is considerable variability in the size of the (small) residual (non-EA) OAA. For a small sample, at the individual journal level, there is not enough variance left for a significant OAA, once one removes the QB component too. Perhaps this is all that Henk Moed wished to imply. But the bigger question for OA concerns all fields, not just those few that are preprint-intensive and that are relatively well-heeled for access to the published version. Indeed, the fundamental OA and OAA questions concern the postprint (not the preprint) and the many disciplines that do have access problems, not the happy few that do not!

The way to test the presence and size of both QB and QA in these non-EA fields is to impose the OA, preferably randomly, on half the sample, and then compare the size of the OAA for imposed ("mandated") self-archiving (Sm) with the size of the OAA for self-selected ("nonmandated") self-archiving (Sn), in particular by comparing their respective ratios to non-self-archived articles in the same journal and year: Sm/N vs. Sn/N).

If Sn/N > Sm/N then QB > QA, and vice versa. If Sn/N = 1, then QB is 0. And if Sm/N = 1 then QA is 0.

It is a first approximation to this comparison that has just been done (FIGURE 3) by my doctoral student, Chawki Hajjem, across fields, for self-archived articles in five Institutional Repositories (IRs) that have OA self-archiving mandates, for 106,203 articles published in 276 biomedical journal 2004, above.

The mandates are still very young and few, hence the sample is still small; and there are many potential artifacts, including selective noncompliance with the mandate as well as disciplinary bias. But the preliminary results so far suggest that (1) QA is indeed > 0, and (2) QA > QB.

[I am sure that we will now have a second round from die-hards who will want to argue for a selective-compliance effect, as a 2nd-order last gasp for the QB-only hypothesis, but of course that loses all credibility as IRs approach 100% compliance: We are analyzing our mandated IRs separately now, to see whether we can detect any trends correlated with an IR's %OA. But (except for the die-hards, who will never die), I think even this early sample already shows that the OA advantage is unlikely to be only or mostly a QB effect.]

HM: "3. Productive versus less productive authors. My analysis of differences in Citation Impact differentials between productive and less productive authors may seem "a little complicated". My point is that if one selects from a set of papers deposited in ArXiv a paper authored by a junior (or less productive) scientist, the probability that this paper is co-authored by a senior (or more productive) author is higher than it is for a paper authored by a junior scientist but not deposited in ArXiv. Next, I found that papers co-authored by both productive and less productive authors tend to have a higher citation impact than articles authored solely by less productive authors, regardless of whether these papers were deposited in ArXiv or not. These outcomes lead me to the conclusion that the observed higher CID for less productive authors compared to that of productive authors can be interpreted as a quality bias."It still sounds a bit complicated, but I think what you mean is that (1) mixed multi-author papers (ML, with M = More productive authors, L = less productive authors) are more likely to be cited than unmixed multi-author (LL) papers with the same number of authors, and that (2) such ML papers are also more likely to be self-archived. (Presumably MM papers are the most cited and most self-archived of multi-author papers.)

That still sounds to me like a variant on the citation/self-archiving correlation, and hence intepretable as either QA or QB or both. (Chawki Hajjem has also found that citation counts are positively correlated with the number of authors an article has: this could either be a self-citation bias or evidence that multi-authored paper tend to be better ones.)

HM: "4. General comments. In the citation analysis by Kurtz et al. (2005), both the citation and target universe contain a set of 7 core journals in astronomy. They explain their finding of no apparent OA effect in his study of these journals by postulating that "essentially all astronomers have access to the core journals through existing channels". In my study the target set consists of a limited number of core journals in condensed matter physics, but the citation universe is as large as the total Web of Science database, including also a number of more peripherical journals in the field. Therefore, my result is stronger than that obtained by Kurtz at al.: even in this much wider citation universe, I do not find evidence for an OA advantage effect."I agree that CondMP is less preprint-intensive, less accessible and less endogamous than Astrophysics, but it is still a good deal more preprint-intensive and accessible than most fields (and I don't yet know what role the exogamy/enodgamy factor plays in either citations or the OAA: it will be interesting to study, among many other candidate metrics, once the entire literature is OA).

HM: "I realize that my study is a case study, examining in detail 6 journals in one subfield. I fully agree with your warning that one should be cautious in generalizing conclusions from case studies, and that results for other fields may be different. But it is certainly not an unimportant case. It relates to a subfield in physics, a discipline that your pioneering and stimulating work (Harnad and Brody, D-Lib Mag., June 2004) has analysed as well at a more aggregate level. I hope that more case studies will be carried out in the near future, applying the methodologies I proposed in my paper."Your case study is very timely and useful. However, robot-based studies based on much larger samples of journals and articles have now confirmed the OAA in many more fields, most of them not preprint-based at all, and with access problems more severe than those of physics.

Conclusions

I would like to conclude with a summary of the "QB vs. QA" evidence to date, as I understand it:

(1) Many studies have reported the OA Advantage, across many fields.This will all be resolved soon, and the outcome of our QA vs. QB comparison for mandated vs. self-selected self-archiving already heralds this resolution. I am pretty confident that the empirical facts will turn out to have been the following: Yes, there is a QB component in the OA advantage (especially in the preprinting fields, such as astro, cond-mat and maths). But that QB component is neither the sole factor nor the largest factor in the OA advantage, particularly in the non-preprint fields with access problems -- and those fields constitute the vast majority. That will be the outcome that is demonstrated, and eventually not only the friends of OA but the foes of OA will have no choice but to acknowledge the new reality of OA, its benefits to research and researchers, and its immediate reachability through the prompt universal adoption of OA self-archiving mandates.

(2) Three studies have reported QB in preprint-intensive fields that have either no postprint access problem or markedly less than other fields (astrophysics, condensed matter, mathematics).

(3) The author of one of these three studies is pro-OA (Kurtz, who is also the one who drew my attention to the QA counterevidence); the author of the second is neutral (Moed); and the author of the third might (I think -- I'm not sure) be mildly anti-OA (Davis -- now collaborating with a publisher to do a 4-year [sic!] long-term study on QA vs QB).Henneken, E. A., Kurtz, M. J., Eichhorn, G., Accomazzi, A., Grant, C., Thompson, D., and Murray, S. S. (2006) Effect of E-printing on Citation Rates in Astronomy and Physics. Journal of Electronic Publishing, Vol. 9, No. 2, Summer 2006(4) So the overall research motivation for testing QB is not an anti-OA motivation.

Moed, H. F. (2006, preprint) The effect of 'Open Access' upon citation impact: An analysis of ArXiv's Condensed Matter Section

Davis, P. M. and Fromerth, M. J. (2007) Does the arXiv lead to higher citations and reduced publisher downloads for mathematics articles? Scientometics, accepted for publication. See critiques: 1, 2

(5) On the other hand, the motivation on the part of some publishers to put a strong self-serving spin on these three QB findings is of course very anti-OA and especially, now, anti-OA-self-archiving-mandate. (That's quite understandable, and no problem at all.)

(6) In contrast to the three studies that have reported what they interpret as evidence of QB (Kurtz in astro, Moed in cond-mat and Davis in maths), there are the many other studies that report large OA citation (and download) advantages, across a large number of fields. Those who have interests that conflict with OA and OA self-archiving mandates are ignoring or discounting this large body of studies, and instead just spinning the three QB reports as their justification for ignoring the larger body of findings.

Stevan Harnad & Chawki Hajjem

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Monday, November 20. 2006

The Self-Archiving Impact Advantage: Quality Advantage or Quality Bias?

Update Jan 1, 2010: See Gargouri, Y; C Hajjem, V Larivière, Y Gingras, L Carr,T Brody & S Harnad (2010) “Open Access, Whether Self-Selected or Mandated, Increases Citation Impact, Especially for Higher Quality Research”

Update Feb 8, 2010: See also "Open Access: Self-Selected, Mandated & Random; Answers & Questions"

Michael Kurtz's papers have confirmed that in astronomy/astrophysics (astro), articles that have been self-archived -- let's call this "Arxived" to mark it as the special case of depositing in the central Physics Arxiv -- are cited (and downloaded) twice as much as non-Arxived articles. Let's call this the "Arxiv Advantage" (AA).

SUMMARY: In astrophysics, Kurtz found that articles that were self-archived by their authors in Arxiv were downloaded and cited twice as much as those that were not. He traced this enhanced citation impact to two factors: (1) Early Access (EA): The self-archived preprint was accessible earlier than the publisher's version (which is accessible to all research-active astrophysicists as soon as it is published, thanks to Kurtz's ADS system). (Hajjem, however, found that in other fields, which self-archive only published postprints and do have accessibility/affordability problems with the publisher's version, self-archived articles still have enhanced citation impact.) Kurtz's second factor was: (2) Quality Bias (QB), a selective tendency for higher quality articles to be preferentially self-archived by their authors, as inferred from the fact that the proportion of self-archived articles turns out to be higher among the more highly cited articles. (The very same finding is of course equally interpretable as (3) Quality Advantage (QA), a tendency for higher quality articles to benefit more than lower quality articles from being self-archived.) In condensed-matter physics, Moed has confirmed that the impact advantage occurs early (within 1-3 years of publication). After article-age is adjusted to reflect the date of deposit rather than the date of publication, the enhanced impact of self-archived articles is again interpretable as QB, with articles by more highly cited authors (based only on their non-archived articles) tending to be self-archived more. (But since the citation counts for authors and for their articles are correlated, one would expect much the same outcome from QA too.) The only way to test QA vs. QB is to compare the impact of self-selected self-archiving with mandated self-archiving (and no self-archiving). (The outcome is likely to be that both QA and QB contribute, along with EA, to the impact advantage.)

Henneken, E. A., Kurtz, M. J., Eichhorn, G., Accomazzi, A., Grant, C., Thompson, D., and Murray, S. S. (2006) Effect of E-printing on Citation Rates in Astronomy and Physics. Journal of Electronic Publishing, Vol. 9, No. 2, Summer 2006Kurtz analyzed AA and found that it consisted of at least 2 components:

Henneken, E. A., Kurtz, M. J., Warner, S., Ginsparg, P., Eichhorn, G., Accomazzi, A., Grant, C. S., Thompson, D., Bohlen, E. and Murray, S. S. (2006) E-prints and Journal Articles in Astronomy: a Productive Co-existence (submitted to Learned Publishing)

Kurtz, M. J., Eichhorn, G., Accomazzi, A., Grant, C. S., Demleitner, M., Murray, S. S. (2005) The Effect of Use and Access on Citations. Information Processing and Management, 41 (6): 1395-1402, December 2005

(1) EARLY ACCESS (EA): There is no detectable AA for old articles in astro: AA occurs while an article is young (1-3 years). Hence astro articles that were made accessible as preprints before publication show more AA: This is the Early Access effect (EA). But EA alone does not explain why AA effects (i.e., enhanced citation counts) persist cumulatively and even keep growing, rather than simply being a phase-advancing of otherwise unenhanced citation counts, in which case simply re-calculating an article's age so as to begin at preprint deposit time instead of publication time should eliminate all AA effects -- which it does not.

(2) QUALITY BIAS (QB): (Kurtz called the second component "Self-Selection Bias" for quality, but I call it self-selection Quality Bias, QB): If we compare articles within roughly the same citation/quality bracket (i.e., articles having the same number of citations), the proportion of Arxived articles becomes higher in the higher citation brackets, especially the top 200 papers. Kurtz interprets this is as resulting from authors preferentially Arxiving their higher-quality preprints (Quality Bias).

Of course the very same outcome is just as readily interpretable as resulting from Quality Advantage (QA) (rather than Quality Bias (QB)): i.e., that the Arxiving benefits better papers more. (Making a low-quality paper more accessible by Arxiving it does not guarantee more citations, whereas making a high-quality paper more accessible is more likely to do so, perhaps roughly in proportion to its higher quality, allowing it to be used and cited more according to its merit, unconstrained by its accessibility/affordability.)

There is no way, on the basis of existing data, to decide between QA and QB. The only way to measure their relative contributions would be to control the self-selection factor: randomly imposing Arxiving on half of an equivalent sample of articles of the same age (from preprinting age to 2-3 years postpublication, reckoning age from deposit date, to control also for age/EA effects), and comparing also with self-selected Arxiving.

We are trying an approximation to this method, using articles deposited in Institutional Repositories of institutions that mandate self-archiving (and comparing their citation counts with those of articles from the same journal/issue that have not been self-archived), but the sample is still small and possibly unrepresentative, with many gaps and other potential liabilities. So a reliable estimate of the relative size of QA and QB still awaits future research, when self-archiving mandates will have become more widely adopted.

Henk Moed's data on Arxiving in Condensed Matter physics (cond-mat) replicates Kurtz's findings in astro (and Davis/Fromerth's, in math):

Moed, H. F. (2006, preprint) The effect of 'Open Access' upon citation impact: An analysis of ArXiv's Condensed Matter SectionMoed too has shown that in cond-mat the AA effect (which he calls CID "Citation Impact Differential") occurs early (1-3 years) rather than late (4-6 years), and that there is more Arxiving by authors of higher-quality (based on higher citation counts for their non-Arxived articles) than by lower-quality authors. But this too is just as readily interpretable as the result of QB or QA (or both): We would of course expect a high correlation between an author's individual articles' citation counts and the author's average citation count, whether the author's citation count is based on Arxived or non-Arxived articles. These are not independent variables.

Davis, P. M. and Fromerth, M. J. (2007) Does the arXiv lead to higher citations and reduced publisher downloads for mathematics articles? Scientometics, accepted for publication. See critiques: 1, 2.

(Less easily interpretable -- but compatible with either QA or QB interpretations -- is Moed's finding of a smaller AA for the "more productive" authors. Moed's explanations in terms of co-authorships between more productive and less productive authors, senior and junior, seem a little complicated.)

The basic question is this: Once the AA has been adjusted for the "head-start" component of the EA (by comparing articles of equal age -- the age of Arxived articles being based on the date of deposit of the preprint rather than the date of publication of the postprint), how big is that adjusted AA, at each article age? For that is the AA without any head-start. Kurtz never thought the EA component was merely a head start, however, for the AA persists and keeps growing, and is present in cumulative citation counts for articles at every age since Arxiving began. This non-EA AA is either QB or QA or both. (It also has an element of Competitive Advantage, CA, which would disappear once everything was self-archived, but let's ignore that for now.)

Harnad, S. (2005) OA Impact Advantage = EA + (AA) + (QB) + QA + (CA) + UA. Preprint.Moed's analysis, like Kurtz's, cannot decide between QB and QA. The fact that most of the AA comes in an article's first 3 years rather than its second 3 years simply shows that both astro and cond-mat are fast-developing fields. The fact that highly-cited articles (Kurtz) and articles by highly-cited authors (Moed) are more likely to be Arxived certainly does not settle the question of cause and effect: It is just as likely that better articles benefit more from Arxiving (QA) as that better authors/articles tend to Arxive/be-Arxived more (QB).

Nor is Arxiv the only test of the self-archiving Open Access Advantage. (Let's call this OAA, generalizing from the mere Arxiving Advantage, AA): We have found an OAA with much the same profile as the AA in 10 further fields, for articles of all ages (from 1 year old to 10 years old), and as far as we know, with the exception of Economics, these are not fields with a preprinting culture (i.e., they don't self-archive preprublication preprints but only postpublication postprints). Hence the consistent pattern of OAA across all fields and across articles of all ages is very unlikely to have been just a head-start (EA) effect.

Hajjem, C., Harnad, S. and Gingras, Y. (2005) Ten-Year Cross-Disciplinary Comparison of the Growth of Open Access and How it Increases Research Citation Impact. IEEE Data Engineering Bulletin 28(4) pp. 39-47.Is the OAA, then, QB or QA (or both)? There is no way to determine this unless the causality is controlled by randomly imposing the self-archiving on a subset of a sufficiently large and representative random sample of articles of all ages (but especially newborn ones) and comparing the effect across time.

In the meantime, here are some factors worth taking into account:

(1) Both astro and and cond-mat are fields where it has been repeatedly claimed that the accessibility/affordability problem for published postprints is either nonexistent (astro) or less pronounced than in other fields. Hence the only scope for an OAA in astro and cond-mat is at the prepublication preprint stage.

(2) In many other fields, however, not only is there no prepublication preprint self-archiving at all, but there is a much larger accessibility/affordability barrier for potential users of the published article. Hence there is far more scope for OAA and especially QA (and CA): Access is a necessary (though not a sufficient) causal precondition for impact (usage and citation).

It is hence a mistake to overgeneralize the phys/math AA findings to OAA in general. We need to wait till we have actual data before we can draw confident conclusions about the degree to which the AA or the OAA are a result of QB or QA or both (and/or other factors, such as CA).

For the time being, I find the hypothesis of a causal QA (plus CA) effect, successfully sought by authors because they are desirous of reaching more users, far more plausible and likely than the hypothesis of an a-causal QB effect in which the best authors are self-archiving merely out of superstition or vanity! (And I suspect the truth is a combination of both QA/CA and QB.)

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Monday, November 13. 2006

Self-Archiving and Journal Subscriptions: Critique of PRC Study