Wednesday, August 31. 2005

Rebuttal to STM Critique of RCUK Research Self-Archiving Policy Proposal

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: The STM (International Society of Scientific, Technical and Medical Publishers) have written a critique of the RCUK (Research Councils of the United Kingdom) research funding policy proposal. Like the ALPSP (Association of Learned and Professional Society Publishers), whose critique of RCUK was rebutted earlier, the STM cites reasons for delaying and modifying the implementation of the RCUK research self-archiving policy. Not one of the cited reasons is valid, and most are based on simple misunderstandings. The biggest of these is that STM is arguing as if RCUK were proposing to mandate a different publishing business model (Open Access [OA] Publishing) whereas RCUK is mandating no such thing: It is merely mandating that RCUK fundees self-archive the final author's drafts of journal articles resulting from RCUK-funded research in order to make their findings accessible online to all potential users whose institutions cannot afford access to the published journal version -- so as to maximise the uptake, usage and impact of British research output. As such, the author's free self-archived version is a supplement to, not a substitute for, the journal's paid version.

STM (like ALPSP) express concern that self-archiving may diminish their revenues. It is pointed out by way of reply (as was pointed out in the reply to ALPSP) that all evidence to date is in fact to the contrary. STM express concern that self-archiving will compromise peer review. It is pointed out that it is the author's peer-reviewed draft that is to be self-archived. STM express concern that self-archiving the author's version will create confusion about versions: It is pointed out that for those would-be users who cannot afford the paid journal version, the author's version is incomparably better than no version at all, and indeed has been demonstrated to enhance citation impact by 50-250%. STM express concern about the costs of Institutional Repositories (IRs): It is pointed out that IRs are neither expensive nor intended as substitutes for journal publishing, so their costs are irrelevant to STM. STM then express concern that the OA publishing business model would cost more than the current subscription-based model: It is pointed out that since the OA model is not what is being mandated by RCUK, cost comparisons are in any case meaningless.

None of these misunderstandings about the nature and objectives of the policy add up to a rationale for deferring or modifying the implementation of the policy in any way at all.

Point-by-point rebuttal of STM response to RCUK self-archiving policy proposal:

STM: "business models must prove to be optimally of service to all constituencies and… decisions and choices [must be] made freely by those constituencies based on open evaluation, not ideology or belief, and without government intervention or mandates"(1) The RCUK access policy for the research it funds is not a business model, and hence not a publishing business model.

(2) The only constituencies involved in setting the conditions on research funding are the British research community itself, plus the British public, which provides the research funds.

(3) No government intervention is involved in research funding. Research funding is disbursed on the basis of peer review and the conditions on its disbursement are set by the research community, based on the interests of research and of the public that provides the research funds.

(4) The decision to use the new medium (the Internet) to maximise the access to and the usage and impact of UK research, in order to maximise the return on the British public’s investment in research is a natural one, and arises from the availability and potential of the new medium. The decision is not based on ideology or belief, but on objective data demonstrating the power of the online medium to enhance research impact.

(5) The mandate to self-archive research in order to maximise its accessibility, usage and impact is no more nor less of a mandate than the mandate to publish research in the first place (or “perish”: i.e., not to be further funded). That researchers should publish their research is presumably an interest of publishers. That researchers should wish to maximise their research’s accessibility, usage and impact should also be a wish of publishers.

(6) Even if it should happen to turn out to be the case that maximising research accessibility, usage and impact -- which is indisputably optimal for research, researchers, research-funders and the British public that funds the funders and for whose benefit the research is being conducted – proves less than optimal for publishers (and there is no evidence that it will so turn out) – then publishers will need to adapt to the new optimum, rather than try to intervene in the conduct of UK research, the disbursement of UK research funds, or the conditions on the disbursement.

STM: "STM fully supports the [RCUK’s first] fundamental principle: (1)… 'public funding should lead to publicly available outputs'”The support is much appreciated, but it is based on a misunderstanding if “publicly available” is taken to mean merely “available for purchase by the general public,” because most peer-reviewed research is not of direct interest to the general public. The British public’s interest is in maximising the impact of the research that it funds, and for that the research must be accessible to the researcher-specialists who will use it, apply it, and build upon it.

Publishers are the providers of paid access to that funded research, for all those researchers and their institutions worldwide that can afford their product, and that is fine. It is fair that publishers should get free value from researchers’ (freely given) output, because they too add value to it -- by implementing the all-important peer review (which researchers themselves provide for free as referees, but publishers administer, funding the services of the expert editors who choose the referees and adjudicate the reviews and revisions) as well as by providing the print product and distribution, and the enriched online product and distribution, with copy-editing, reference-linking, mark-up and many other valuable enhancements. It is only fair that publishers should be able to recover their costs and make a fair return on their investment in exchange for the value they add.

But researchers (and research) are also concerned with the potential usage and impact from those researchers whose institutions cannot afford their publishers’ value-added product. A growing body of evidence across all fields is now demonstrating that those articles for which journal access to the publisher’s value-added version is supplemented by a self-archived version of the author’s own final draft have 50-250% greater citation impact than those for which only the paid version is accessible.

It is in order to close this 50-250% research impact gap that RCUK is mandating self-archiving for the research it funds; and it is in this way that the British public’s interest in maximising the return on its research investment is best served. (We will return to this when we deal with STM’s analogy to “public transport.”)

STM: "the RCUK conclusions are precipitous and lack scientific rigour"On the contrary. All the scientific evidence (see bibliography) supports the RCUK’s conclusions, and the evidence is very strong: Self-archiving has been demonstrated to enhance research impact dramatically. What would be unscientific – indeed illogical – would be to imagine that the optimal conditions under which to fund research are somehow connected with publishers’ business models (one way or the other). Publishers make a valuable contribution to research communication, but research is not done in the interests of supporting the publishing business. Publishers are meant to be helping to increase the usage and impact of research, not to be trying to prevent it from being increased.

Nor are the conclusions precipitous in the least. They have a long history, starting in the early 1990’s and even earlier, with various memorable milestones since then, such as Harold Varmus’s Ebiomed Proposal in 1999, the Public Library of Science Open Letter in 2001, and the UK Select Committee deliberations in 2003. All sides have been heard across these years, many times over; the optimal path has already been extensively tested and demonstrated to enhance research usage and impact dramatically; and that path has already been embarked upon by about 15% of the world research community: Self-archiving needs to be done to supplement paid access, so as to make research accessible online to 100% of its would-be users world-wide, not just the percentage who can afford paid access to the publisher's version. Those access-denied users are the cause of the 50-250% impact gap. And that gap is what the RCUK policy proposes to close for UK research output. That policy is not precipitous but obvious, optimal, and long overdue.

STM: "[RCUK] appear to presuppose that there are unsolvable problems in the current scholarly information system, without debate or analysis"Not at all: The problem (providing access to British research for those researchers in the UK and worldwide who cannot afford paid access, in order to maximise British research impact and progress) is eminently solvable, and RCUK has proposed exactly the right solution. What there has been, exclusively, for too many years now is debate. The experimental testing and logical analysis have been conducted. The results are in. Self-archiving works, and it delivers what it promises to deliver: 50-250% greater research impact. And it does so within the “current scholarly information system,” without any change in business models, through just the extra few keystrokes it takes for authors to deposit their final draft when it is accepted for publication.

STM: "we think… the creation of a new more routinised publishing system through RCUK-mandated repositories and systems as proposed will [1] decrease diversity in journals and the peer review process… [2] threaten the value of investments made by STM publishers… [3] improve neither access nor quality for scholars… [4] exacerbate the… problem of differing versions of research papers… with researchers unsure… which… has been subject to peer review"First, there has been no proposal for a “new, more routinised publishing system.” The RCUK is proposing a supplement to the current publishing system: self-archiving the author’s version for those would-be users whose institutions cannot afford the publisher’s value-added version.

(1) This does not entail any change in either the diversity of journals or the rigour of the peer review process. (Authors are to self-archive their own final drafts of articles that they continue to publish in the current peer-reviewed journals, leaving both their diversity and their peer review untouched.)

(2) There is no evidence at all that self-archiving has any effect on the investments of STM publishers. Self-archiving has been practiced for nearly 15 years now, and in some subfields of physics it has even reached 100%, yet both of the major physics publishers (APS and IOPP) report that they can detect no cancellations associated with this growth.

(3) There is now a great deal of incontestable evidence that self-archiving improves both access and impact for scholars. (No claims were made that it would improve research quality -- though that has not been tested: it may well be the case that enhanced access, usage and impact enhance research quality too!)

(4) There is no “version problem,” there is an access problem: Those researchers who cannot afford access to the publisher’s version are not the ones raising the hue and cry about versions. Is STM proposing to speak for them, suggesting that they should rather do without than be subjected to access to the author’s version?

STM: "There is substantial and compelling evidence that the current publishing and licensing systems of STM publishers [have] created a vibrant research infrastructure in the UK in which all four RCUK principles are embodied and are functioning with enormous success. There is no evidence to the contrary, although there are concerns about appropriate budgeting to support ever-increasing research outputs"The RCUK policy to supplement paid access to the journal version with free access to the author’s self-archived version for those would-be users who cannot afford the journal version does not imply that the journal version does not continue to be valuable, vibrant or successful. The evidence that we can still do much better comes from the 50-250% impact enhancement data.

STM: "The Government itself, in its November 2004 response (the “UK Government Response”) to the report of the Science and Technology Committee of the House of Commons called “Scientific Publications: Free for All?”, noted that it did not see any 'major problems in accessing scientific information', nor “any evidence of a significant problem in meeting the public’s needs in respect of access to journals…'”The government evidently did not see (or perhaps understand) the growing body of access/impact data. But the RCUK (being researchers) evidently did.

STM: "[Even though] most STM member publishers permit authors to deposit their works in the authors’ institutional repositories (“IR” or “IRs”), such repositories do not appear yet to have created a substantial archive of research material."It is not clear exactly what STM mean here, but if they mean that there are not yet enough IRs in the UK and they do not yet archive most of their own institutional research output, STM are quite right, and that is one of the things the RCUK policy is intended to remedy.

STM: "Only about a fifth of the CIBER survey respondents had deposited"That sounds right. Estimates of the current proportion of annual research article output that is currently being self-archived vary by field, but they all hover around 15%, as noted (though a recent JISC survey finds that 49% of authors report having self-archived at least once).

The purpose of the RCUK policy is to raise that 15% to 100% for UK research output.

STM: "Institutional repositories do not seem to be able to provide improved access to verified research results"Now this observation, in contrast to the preceding one, is very far from correct! Author self-archiving (whether in IRs or anywhere else on the web) has been demonstrated in field after field to improving research citation impact by 50-250%. Since citing research results is rather more than just accessing them, we can safely conclude that self-archiving must be improving access by at least that much too.

What is certainly true is that providing Institutional Repositories for them is not enough to induce enough UK researchers to self-archive spontaneously: The same JISC survey that was cited above has also reported exactly what more is needed, and it was the authors who indicated what that was: an employer/funder requirement to self-archive. Of the over 1200 authors surveyed, 95% replied that they would comply with such a requirement – and the only two institutions that have already adopted such a requirement (University of Southampton’s ECS Department and CERN Laboratory in Switzerland) both report over 90% compliance, exactly as predicted by the JISC survey.

(And, by way of a reminder: the author’s final, refereed, accepted draft is the “verified research results.”)

STM: "the potential costs to improve such repositories to enable them to be successful have not been analysed properly to determine whether they are significantly less expensive than current publishing models."It is very thoughtful of STM to worry about IR costs for the research community (just as it worried about the risks of exposure to the author’s version) but STM will be reassured that the costs of creating and maintaining IRs are not only risibly small (amounting to less than $10 per paper), but they are irrelevant. Because what IRs need in order to be successful is not pennies but the RCUK policy itself (as the JISC study showed), requiring researchers to deposit their “verified research results.”

In any case, the costs of self-archiving have nothing whatsoever to do with the costs of publishing, since self-archiving is not a substitute but a supplement, provided to those who cannot afford the costs of the published version. Self-archiving in IRs is not a competing business model for publishing, but a complement to the existing publishing system.

STM: "‘public access’ does not necessarily mean ‘free access’, in the same way as ‘public transport’ does not mean ‘free transport’, even though in this country tax payers seem to contribute as significantly to the latter as they do to scientific research."“Public access” does not mean free access, but “open access” does. And open access is concerned with goods from which (unlike the products and services of the public transport industry) one of the two co-producers (and the primary one) seeks and receives no sales revenue whatsoever: The researchers give their writings to their publishers, without asking any royalties or fees, in exchange for the peer review and publication they receive, which in turn brings them a certain measure of research impact, which is what they really seek. But in the online age it turns out that researchers are losing 50-250% of their potential impact if they do not, in addition to giving away their research to their publishers for free, also give it away online for free.

Moreover, there is in a sense a third co-producer, or at least a co-investor in the “product,” along with the researcher and the publisher, and that is the British public, the tax-payer who funds the research: Like the researcher and the researcher’s institution, the public’s interest is in maximising the degree to which its research investment is used, applied and built-up, in other words, maximising its impact, which in turn depends on maximising access to it.

The publisher is a co-producer, having added value, and is fully entitled to seek revenue for that contribution. (The publisher, after all, unlike the researcher, is not publishing merely for impact – although the publisher too co-benefits from enhanced impact.) But the researcher (and the third co-producer, the public) are just as entitled to supplement the impact that their research receives from the publisher’s version with the potential impact from the self-archived supplement, provided for those who cannot afford access to the publisher’s version (exactly as reprints were provided by authors to reprint-requesters in paper days).

(Now please find a counterpart for all that in the “public transport industry” analogy!)

STM: "The concept of ‘reasonable access’ is probably more appropriate in this case."What is reasonable is that when a new medium is invented that makes it possible to increase research access and impact substantially, no one should try to restrict research impact simply because such a possibility had not existed in paper days. Or, more succinctly, it is not reasonable to expect research and researchers and the public that funds them to renounce potential research impact in the online era.

STM: "Researchers report a high level of trust in existing peer-reviewed journals."Indeed they do. And it is the articles published in those trusted peer-reviewed journals of which the author’s versions are now to be self-archived in order to maximise their research impact, in accordance with the RCUK policy.

STM: "Quality can always be improved, but it is difficult to imagine how author-pays business models or repositories will be more effective with respect to quality than existing publishing systems."That may well be, but it is absolutely irrelevant to the matter at hand, since the RCUK is not proposing to mandate author-pays business models, but author self-archiving. And it is not mandating self-archiving primarily to improve quality but to improve impact. And in this respect the IRs are a means (to improve impact), not an end in themselves (although IRs have other institutional uses too).

STM: "Mandating a centralised peer review system for repositories will not be an improvement on the current journal-based and highly diverse review procedures."That is absolutely correct, and no one is proposing to mandate a centralised peer review system for repositories. RCUK is proposing to mandate the self-archiving of the author’s version of peer-reviewed journal articles.

STM: "the argument has often been made (and never successfully refuted) that the mixing of scientific and financial barriers to an author accessing the journal of his/her choice may lead to unintended consequences with respect to reviewing standards."The argument may (or may not) be sound, but it is absolutely irrelevant to the matter at hand, since the RCUK is not proposing to mandate the mixing of scientific/financial values, nor to mandate the author’s choice of journal. RCUK is proposing to mandate the self-archiving of the author’s version of peer-reviewed journal articles.

STM: "Many reports have now indicated that major research institutions would have to pay more for author-pays business models than in the traditional subscription models."That may (or may not) be true, but it is absolutely irrelevant to the matter at hand, since the RCUK is not proposing to mandate author-pays business models, but self-archiving

STM: "The cost of maintaining a large number of independent repositories…is likely to be significantly higher and less cost-effective than current publisher-hosted systems."It is again gratifying that STM is so concerned about RCUK and university IR costs, but let them be reassured that not only are those costs happily low, but IRs are not intended to be substitutes for publisher-hosted systems but supplements to them, to end the access-denial for (and resulting impact loss from) those researchers who cannot afford the publisher’s version. Hence there is not even any point in comparing their costs, which are orthogonal.

STM: "STM agrees that there are significant and important concerns about the ever-increasing gap between the relatively high level of research funding, resulting in ever-increasing output of research results, and the relatively static level of library funding. This issue deserves serious debate and consideration, but the RCUK proposals do not seriously address these issues, if at all."That is correct. The RCUK policy is not intended to generate more revenue to pay for more paid access, but to supplement the existing paid access, such as it is, for those would-be users who cannot afford it, in order to maximise the impact of the research that the RCUK funds.

STM: "The British Library maintains one of the most complete academic libraries in the world, and the university research library community is similarly focused on preservation. Many UK university libraries now have access to very large collections of STM journals… The cost of duplicating such archives in digital form on various e-repositories, as appears to be suggested by the RCUK, is daunting and unnecessary."Journals are not to be duplicated; authors’ drafts are to be self-archived, to maximise their impact. The costs, such as they are, are not pertinent to STM, so it is unnecessary for STM to be daunted by them.

STM: "we welcome new publishers and new business models to our markets. We see nothing new in the RCUK proposal other than unfunded mandates that arbitrarily favour some models over others."The RCUK proposal is not about new publishers or new business models, nor does it favour any model. It is about self-archiving RCUK-funded research in order to maximise UK research impact. (It is unfunded because both IRs and keystrokes are distributed and cheap, and that’s all that’s needed.)

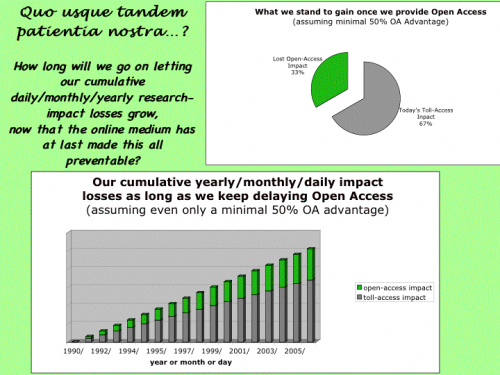

STM: "STM submits that the research community, and the four RCUK principles, are well served by the many dynamic business models that are currently in existence and experimented with, as a result of competition and innovation, in the marketplace."STM may well be right. But well-served as they are, the British research community would quite like to improve this excellent service with the 50-250% impact that the 85% of British research that is not yet self-archived is still currently losing, needlessly, daily, monthly, and yearly.

STM: "In summary, STM believes that it would be in the interest of the research community and the broader community as a whole if STM and RCUK start a serious and systematic dialogue, based on the mutually agreed “four principles”, by jointly assessing and evaluating areas where the research information infrastructure can be improved and working with both the publishing and research communities to achieve this, including by the development of mediation and investigative bodies for research ethics issues, the support of the development of technical standards to identify versions and forms of research papers, and the like. This way we can all avoid the trap of prematurely promoting solutions that are based on unproven assumptions."It is an excellent idea for STM to confer and collaborate with RCUK on ways to improve things over and above the long-overdue self-help policy that the RCUK is already planning to adopt for British research output. Such collaboration would be very useful – but certainly not instead of implementing the self-archiving policy, as and when planned. None of the above misunderstandings about the nature and objectives of the policy, nor all the irrelevant points about alternative business models, add up to any sort of rationale for deferring or diverting the implementation of the policy in any way at all.

Stevan Harnad

Open Letter to Research Councils UK: Rebuttal of STM Critique

31 August 2005

Professor Ian Diamond

Chair, RCUK Executive Group

Councils UK Secrerariat

Polaris House North Star Ave

Swindon SN2 1ET UK

Dear Ian,

The STM have written a response to the RCUK proposal in which they too, like the ALPSP a few weeks ago, adduce reasons for delaying and modifying the implementation of the RCUK self-archiving policy.

As in the (short and long) replies to ALPSP, the STM points are very readily rebutted: Most are based on rather profound (and surprising) but easily corrected misunderstandings about the policy itself, and its purpose. A few points are based on a perceived conflict of interest between what is demonstrably best for British research and the British public's investment in it and what STM sees as best for the STM publishing industry.

The principal substantive misunderstanding about the RCUK policy itself is that the STM is arguing as if RCUK were proposing to mandate a different publishing business model (Open Access [OA] Publishing) whereas RCUK is proposing to mandate no such thing: It is merely proposing to mandate that RCUK fundees self-archive the final author's drafts of journal articles resulting from RCUK-funded research in order to make their findings accessible to all potential users whose institutions cannot afford access to the published journal version -- in order to maximise the uptake, usage and impact of British research output. As such, the author's free self-archived version is a supplement to, not a substitute for, the journal's paid version.

STM (like ALPSP) express concern that self-archiving may diminish their revenues. It is pointed out by way of reply (as was pointed out in the reply to ALPSP) that all evidence to date is in fact to the contrary. STM express concern that self-archiving will compromise peer review. It is pointed out that it is the author's peer-reviewed draft that is being self-archived. STM express concern that self-archiving the author's version will create confusion about versions: It is pointed out that for those would-be users who cannot afford the paid journal version, the author's version is incomparably better than no version at all, and indeed has been demonstrated to enhance citation impact by 50-250%. STM express concern about the costs of Institutional Repositories (IRs): It is pointed out that IRs are neither expensive nor intended as substitutes for journal publishing, so their costs are irrelevant to STM. STM then express concern that the OA publishing business model would cost more than the current subscription-based model: It is pointed out that the OA model is not what is being mandated by RCUK.

The point-by-point rebuttal follows [next blog entry]. It is quite clear that the STM has no substantive case at all for delaying or modifying the RCUK policy proposal in any way.

I would close by suggesting that it would help clarify the RCUK policy if the abstract ideological points, which currently have no concrete implications in practice, were either eliminated or separated from the concrete policy recommendation (which is to require self-archiving and perhaps to help fund OA publication costs). The 'preservation' components are also misplaced, as the mandate is to self-archive the author's draft, not the publisher's version (which is the one with the preservation problem). It would also be good to remove the confusing mumbo-jumbo about 'kite-marking' so that ALPSP and STM cannot argue that RCUK is proposing to tamper with peer review. And the less said about publishing models, the better, as that is not what RCUK is mandating.

Best wishes,

Stevan Harnad

Professor of Cognitive Sciences

Department of Electronic and Computer Science

University of Southampton

Southampton UK

SO17 1BJ

Pertinent Prior AmSci Topic Threads:

"ALPSP Response to RCUK Policy Proposal" (began Jul 2005) -- 1 -- 2 -- 3 -- 4

"Critique of STM Critique of NIH Proposal" (began Nov 2004)

"STM Talk: Open Access by Peaceful Evolution" (began Feb 2003)

"Book on future of STM publishers" (began Jul 2002)

Professor Ian Diamond

Chair, RCUK Executive Group

Councils UK Secrerariat

Polaris House North Star Ave

Swindon SN2 1ET UK

Dear Ian,

The STM have written a response to the RCUK proposal in which they too, like the ALPSP a few weeks ago, adduce reasons for delaying and modifying the implementation of the RCUK self-archiving policy.

As in the (short and long) replies to ALPSP, the STM points are very readily rebutted: Most are based on rather profound (and surprising) but easily corrected misunderstandings about the policy itself, and its purpose. A few points are based on a perceived conflict of interest between what is demonstrably best for British research and the British public's investment in it and what STM sees as best for the STM publishing industry.

The principal substantive misunderstanding about the RCUK policy itself is that the STM is arguing as if RCUK were proposing to mandate a different publishing business model (Open Access [OA] Publishing) whereas RCUK is proposing to mandate no such thing: It is merely proposing to mandate that RCUK fundees self-archive the final author's drafts of journal articles resulting from RCUK-funded research in order to make their findings accessible to all potential users whose institutions cannot afford access to the published journal version -- in order to maximise the uptake, usage and impact of British research output. As such, the author's free self-archived version is a supplement to, not a substitute for, the journal's paid version.

STM (like ALPSP) express concern that self-archiving may diminish their revenues. It is pointed out by way of reply (as was pointed out in the reply to ALPSP) that all evidence to date is in fact to the contrary. STM express concern that self-archiving will compromise peer review. It is pointed out that it is the author's peer-reviewed draft that is being self-archived. STM express concern that self-archiving the author's version will create confusion about versions: It is pointed out that for those would-be users who cannot afford the paid journal version, the author's version is incomparably better than no version at all, and indeed has been demonstrated to enhance citation impact by 50-250%. STM express concern about the costs of Institutional Repositories (IRs): It is pointed out that IRs are neither expensive nor intended as substitutes for journal publishing, so their costs are irrelevant to STM. STM then express concern that the OA publishing business model would cost more than the current subscription-based model: It is pointed out that the OA model is not what is being mandated by RCUK.

The point-by-point rebuttal follows [next blog entry]. It is quite clear that the STM has no substantive case at all for delaying or modifying the RCUK policy proposal in any way.

I would close by suggesting that it would help clarify the RCUK policy if the abstract ideological points, which currently have no concrete implications in practice, were either eliminated or separated from the concrete policy recommendation (which is to require self-archiving and perhaps to help fund OA publication costs). The 'preservation' components are also misplaced, as the mandate is to self-archive the author's draft, not the publisher's version (which is the one with the preservation problem). It would also be good to remove the confusing mumbo-jumbo about 'kite-marking' so that ALPSP and STM cannot argue that RCUK is proposing to tamper with peer review. And the less said about publishing models, the better, as that is not what RCUK is mandating.

Best wishes,

Stevan Harnad

Professor of Cognitive Sciences

Department of Electronic and Computer Science

University of Southampton

Southampton UK

SO17 1BJ

Pertinent Prior AmSci Topic Threads:

"ALPSP Response to RCUK Policy Proposal" (began Jul 2005) -- 1 -- 2 -- 3 -- 4

"Critique of STM Critique of NIH Proposal" (began Nov 2004)

"STM Talk: Open Access by Peaceful Evolution" (began Feb 2003)

"Book on future of STM publishers" (began Jul 2002)

Press Coverage of Imminent RCUK Decision on Self-Archiving Policy Proposal

The imminent UK Research Councils' (RCUK) decision on their self-archiving policy proposal is receiving considerable press coverage in the UK:

Results of publicly funded research should be available to all, says web creator [Tim Berners-Lee] Zosia Kmietowicz British Medical Journal 3 September 2005.

The infrastructure is there: time to populate Vanessa Spedding Research Information July/August 2005.

ALPSP and academics fight it out over Research Councils UK IR rules Mark Chillingworth Information World Review 31 August 2005.

Critiques and rebuttals continue in UK open access debate Cordis News 31 August 2005.

Scientists reignite open access debate

Clive Cookson, Science Editor, Financial Times, Wednesday, August 31 2005

ALPSP and academics fight it out over Research Councils UK IR rules

Mark Chillingworth, Information World Review 31 August 2005

Publishers make last stand against open access

Donald MacLeod, Education Guardian, Tuesday, August 30 2005

Publish university science for free, urges web creator [Tim Berners-Lee]

Richard Wray The Guardian & The Observer, Tuesday, August 30 2005

BBC Scotland (Radio)

Newsdrive, Tuesday, August 3o (16:25) 2005

(click "Listen Again" for the Tuesday broadcast; item is at about 16:25)

Tuesday, August 23. 2005

Pascal's Wager and Open Access

Sally Morris (ALPSP) wrote in the SPARC Open Access Forum:

Second, there is no evidence to refute Creationism either: Just no evidence for it, and all existing evidence against it (in both cases). So one can only rebut, not refute, in both cases. (I might add that the ALPSP reponse is likewise merely rebutting RCUK, not refuting, but the difference is that the ALPSP adduce no valid evidence in support of their rebuttal, and that is precisely what our rebuttal points out: along with the positive evidence in support of the RCUK policy and contrary to the ALPSP rebuttal).

I suggest that Sally look into the logic of hypothesis-testing and empirical inference. One does not, in the real empirical world, say "I conjecture, and you cannot refute": Refutation (disproof) is only possible in mathematics -- by proving that something is logically impossible, self-contradictory. For anything else that is not logically impossible, we seek not refutation but supporting or contrary evidence. For the proposition "Self-archiving will ruin journals" (or even that it will reduce subscriptions) there is no supporting evidence to date, and all evidence to date is to the contrary: that self-archiving is neither ruining journals nor even reducing their subscriptions.

Sally would do well to look at "Pascal's Wager" (as I have urged her to do before):

Pascal thought that it was more rational to behave as-if the Creed (that there is an afterlife, with eternal damnation for nonbelievers) were true, because the costs of behaving as if the Creed were false if it was in fact true (eternal damnation) were so much greater than the costs of behaving as if the Creed were true even if it was in fact false (leading a slightly more constrained but finite life).

What Pascal missed was that the force of this unassailable logic came from one unquestioned but questionable premise: The (arbitrary) threat of eternal damnation, merely on the Prophets' say-so. It was the direness of the purported consequences that made the logic look unassailable. (Any rival Prophet could have raised the Wager by promising even more dire consequences [e.g., one's soul splitting into an infinity of sub-souls, all suffering one another's anguish for an eternity of cardinality Aleph-1, where each instant lasts an eternity] if one fails to behave according to that Creed, and so on.)

What this shows is that one does not make a point by just positing the dire consequences that would ensue if one does not take the point.

I, for my part, am not prophecying ruin for research if researchers fail to self-archive. I am merely demonstrating exactly what research and researchers are actually losing, daily, monthly, yearly, as long as they don't:

Sally should give up the Doomsday business too...

Stevan Harnad

SM:There's a difference between 'refute' (= produce evidence to disprove) and 'rebut' (= argue against). Stevan's letter does the latter, not the former; there is no evidence whatever that self-archiving will not damage journals or those who produce them.(Umm, first, that's Berners-Lee et al's letter, not Stevan's letter...;>)

Second, there is no evidence to refute Creationism either: Just no evidence for it, and all existing evidence against it (in both cases). So one can only rebut, not refute, in both cases. (I might add that the ALPSP reponse is likewise merely rebutting RCUK, not refuting, but the difference is that the ALPSP adduce no valid evidence in support of their rebuttal, and that is precisely what our rebuttal points out: along with the positive evidence in support of the RCUK policy and contrary to the ALPSP rebuttal).

I suggest that Sally look into the logic of hypothesis-testing and empirical inference. One does not, in the real empirical world, say "I conjecture, and you cannot refute": Refutation (disproof) is only possible in mathematics -- by proving that something is logically impossible, self-contradictory. For anything else that is not logically impossible, we seek not refutation but supporting or contrary evidence. For the proposition "Self-archiving will ruin journals" (or even that it will reduce subscriptions) there is no supporting evidence to date, and all evidence to date is to the contrary: that self-archiving is neither ruining journals nor even reducing their subscriptions.

Sally would do well to look at "Pascal's Wager" (as I have urged her to do before):

Pascal thought that it was more rational to behave as-if the Creed (that there is an afterlife, with eternal damnation for nonbelievers) were true, because the costs of behaving as if the Creed were false if it was in fact true (eternal damnation) were so much greater than the costs of behaving as if the Creed were true even if it was in fact false (leading a slightly more constrained but finite life).

What Pascal missed was that the force of this unassailable logic came from one unquestioned but questionable premise: The (arbitrary) threat of eternal damnation, merely on the Prophets' say-so. It was the direness of the purported consequences that made the logic look unassailable. (Any rival Prophet could have raised the Wager by promising even more dire consequences [e.g., one's soul splitting into an infinity of sub-souls, all suffering one another's anguish for an eternity of cardinality Aleph-1, where each instant lasts an eternity] if one fails to behave according to that Creed, and so on.)

What this shows is that one does not make a point by just positing the dire consequences that would ensue if one does not take the point.

I, for my part, am not prophecying ruin for research if researchers fail to self-archive. I am merely demonstrating exactly what research and researchers are actually losing, daily, monthly, yearly, as long as they don't:

Sally should give up the Doomsday business too...

Stevan Harnad

Monday, August 22. 2005

Journal Publishing and Author Self-Archiving: Peaceful Co-Existence and Fruitful Collaboration

Tim Berners-Lee (UK, Southampton & US, MIT)

Dave De Roure (UK, Southampton)

Stevan Harnad (UK, Southampton & Canada, UQaM)

Derek Law (UK, Strathclyde)

Peter Murray-Rust (UK, Cambridge)

Charles Oppenheim (UK, Loughborough)

Nigel Shadbolt (UK, Southampton)

Yorick Wilks (UK, Sheffield)

Subbiah Arunachalam (India, MSRF)

Helene Bosc (France, INRA, ret.)

Fred Friend (UK, University College, London)

Andrew Odlyzko (US, University of Minnesota)

Arthur Sale (Australia, University of Tasmania)

Peter Suber (US, Earlham)

SUMMARY: The UK Research Funding Councils (RCUK) have proposed that all RCUK fundees should self-archive on the web, free for all, their own final drafts of journal articles reporting their RCUK-funded research, in order to maximise their usage and impact. ALPSP (a learned publishers' association) now seeks to delay and block the RCUK proposal, auguring that it will ruin journals. All objective evidence from the past decade and a half of self-archiving, however, shows that self-archiving can and does co-exist peacefully with journals while greatly enhancing both author/article and journal impact, to the benefit of both. Journal publishers should not be trying to delay and block self-archiving policy; they should be collaborating with the research community on ways to share its vast benefits.This is a public reply, co-signed by the above, to the August 5, 2005, public letter by Sally Morris, Executive Director of ALPSP (Association of Learned and Professional Society Publishers) to Professor Ian Diamond, Chair, RCUK (Research Councils UK), concerning the RCUK proposal to mandate the web self-archiving of authors' final drafts of all journal articles resulting from RCUK-funded research, making them freely accessible to all researchers worldwide who cannot afford access to the official journal version, in order to maximise the usage and impact of the RCUK-funded research findings.

It is extremely important that the arguments and objective evidence for or against the optimality of research self-archiving policy be aired and discussed openly, as they have been for several years now, all over the world, so that policy decisions are not influenced by one-sided arguments from special interests that can readily be shown to be invalid. Every single one of the points made by the ALPSP below is incorrect -- incorrect from the standpoint of both objective evidence and careful logical analysis. We accordingly provide a point by point rebuttal here, along with a plea for an end to publishers' efforts to block or delay self-archiving policy -- a policy that is undeniably beneficial to research and researchers, as well as to their institutions and the public that funds them. Publishers should collaborate with the research community to share the benefits of maximising research access and impact.

(Please note that this is not the first time the ALPSP's points have been made, and rebutted; but whereas the rebuttals take very careful, detailed account of the points made by ALPSP, the ALPSP unfortunately just keeps repeating its points without taking any account of the detailed replies. By way of illustration, the prior ALPSP critique of the RCUK proposal (April 19) was followed on July 1 by a point-by-point rebuttal. The reader who compares the two cannot fail to notice certain recurrent themes that ALPSP keeps ignoring in their present critique. In particular, 3 of the 5 examples that ALPSP cites below as evidence of the negative effects of self-archiving on journals turn out to have nothing at all to do with self-archiving, exactly as pointed out in the earlier rebuttal. The other 2 examples turn out to be positive evidence for the potential of sharing the benefits through cooperation and collaboration between the research and publishing community, rather than grounds for denying research and researchers those benefits through opposition.)

All quotes are from

ALPSP response to RCUK's proposed position statement on access to research outputswhich was addressed to: Professor Ian Diamond, Research Councils UK Secretariat on 5th August, 2005:

ALPSP: "Although the mission of our publisher members is to disseminate and maximise access to research information"The principle of maximising access to research information is indeed the very essence of the issue at hand. The reader of the following statements and counter-statements should accordingly bear this principle in mind while weighing them: Unlike the authors of books or of magazine and newspaper articles, the authors of research journal articles are not writing in order to sell their words, but in order to share their findings, so other researchers can use and build upon them, in order to advance research progress, to the benefit of the public that funded the research. This usage and application is called research impact. Research impact is a measure of research progress and productivity: the influence that the findings have had on the further course of research and its applications; the difference it has made that a given piece of research has been conducted at all, rather than being left unfunded and undone. Research impact is the reason the public funds the research and the reason researchers conduct the research and report the results. Research that makes no impact may as well not have been conducted at all. One of the primary indicators -- but by no means the only one -- of research impact is the number of resulting pieces of research by others that make use of a finding, by citing it. Citation counts are accordingly quantitative measures of research impact. (The reader is reminded, at this early point in our critique, that it is impossible for a piece of research to be read, used, applied and cited by any researcher who cannot access it. Research access is a necessary (though not a sufficient) condition for research impact.)

Owing to this central importance of impact in the research growth and progress cycle, the authors of research are rewarded not by income from the sales of their texts, like normal authors, but by 'impact income' based on how much their research findings are used, applied, cited and built upon. Impact is what helps pay the author's salary, what brings further RCUK grant income, and what brings RAE (Research Assessment Exercise) income to the author's institution. And the reason the public pays taxes for the RCUK and RAE to use to fund research in the first place is so that that research can benefit the public -- not so that it can generate sales income for publishers. There is nothing wrong with research also generating sales income for publishers. But there is definitely something wrong if publishers try to prevent researchers from maximising the impact of their research, by maximising access to it. For whatever limits research access limits research progress; to repeat: access is a necessary condition for impact.

Hence, for researchers and their institutions, the need to 'maximise access to research information' is not just a pious promotional slogan: Whatever denies access to their research output is denying the public the research impact and progress it paid for and denying researchers and their institutions the impact income they worked for. Journals provide access to all individuals and institutions that can afford to subscribe to them, and that is fine. But what about all the other would-be users -- those researchers world-wide whose institutions happen to be unable to afford to subscribe to the journal in which a research finding happens to be published? There are 24,000 research journals and most institutions can afford access only to a small fraction of them. Across all fields tested so far (including physics, mathematics, biology, economics, business/management, sociology, education, psychology, and philosophy), articles that have been self-archived freely on the web, thereby maximising access, have been shown to have 50%-250+% greater citation impact than articles that have not been self-archived. Is it reasonable to expect researchers and their institutions and funders to continue to renounce that vast impact potential in an online age that has made this impact-loss no longer necessary? Can asking researchers to keep on losing that impact be seriously described as 'maximising access to research information'? Now let us see on what grounds researchers are being asked to renounce this impact:

ALPSP: "we find ourselves unable to support RCUK's proposed position paper on the means of achieving this. We continue to stress all the points we made in our previous response, dated 19 April, and are insufficiently reassured by RCUK's reply. We are convinced that RCUK's proposed policy will inevitably lead to the destruction of journals."If it were indeed true that the RCUK's policy will inevitably lead to the destruction of journals, then this contingency would definitely be worthy of further time and thought.

But there is in fact no objective evidence whatseover in support of this dire prophecy. All evidence (footnote 1) from 15 years of self-archiving (in some fields having reached 100% self-archiving long ago) is exactly the opposite: that self-archiving and journal publication can and do continue to co-exist peacefully, with institutions continuing to subscribe to the journals they can afford, and researchers at the institutions that can afford them continuing to use them; the only change is that the author's own self-archived final drafts (as well as earlier pre-refereeing preprints) are now accessible to all those researchers whose institutions could not afford the official journal version (as well as to any who may wish to consult the pre-refereeing preprints). In other words, the self-archived author's drafts, pre- and post-refereeing, are supplements to the official journal version, not substitutes for it.

In the absence of any objective evidence at all to the effect that self-archiving reduces subscriptions, let alone destroys journals, and in the face of 15 years' worth of evidence to the contrary, ALPSP simply amplifies the rhetoric, elevating pure speculation to a putative justification for continuing to delay and oppose a policy that is already long overdue and a practice that has already been amply demonstrated to deliver something of immense benefit to research, researchers, their institutions and funders: dramatically enhanced impact. All this, ALPSP recommends, is to be put on hold because some publishers have the 'conviction' that self-archiving will destroy journals.

ALPSP: "A policy of mandated self-archiving of research articles in freely accessible repositories, when combined with the ready retrievability of those articles through search engines (such as Google Scholar) and interoperability (facilitated by standards such as OAI-PMH), will accelerate the move to a disastrous scenario."The objective evidence from 15 years of continuous self-archiving by physicists (even longer by computer scientists) has in fact tested this grim hypothesis; and this cumulative evidence affords not the slightest hint of any move to a 'disastrous scenario.' Throughout the past decade and a half, final drafts of hundreds of thousands of articles have been made freely accessible and readily retrievable by their authors (in some fields approaching 100% of the research published). And these have indeed been extensively accessed and retrieved and used and applied and cited by researchers in those disciplines, exactly as their authors intended (and far more extensively than articles for which the authors' drafts had not been made freely accessible). Yet when asked, both of the large physics learned societies (the Institute of Physics Publishing in the UK and the American Physical Society) responded very explicitly that they could identify no loss of subscriptions to their journals as a result of this critical mass of self-archived and readily retrievable physics articles (footnote 1). The ALPSP's doomsday conviction does not gain in plausibility by merely being repeated, ever louder.

Google Scholar and OAI-PMH do indeed make the self-archived supplements more accessible to their would-be users, but that is the point: The purpose of self-archiving is to maximise access to research information. (Some publishers may still be in the habit of reckoning that research is well-served by access-denial, but the providers of that research -- the researchers themselves, and their funders -- can perhaps be forgiven for reckoning, and acting, otherwise.)

ALPSP: "Librarians will increasingly find that 'good enough' versions of a significant proportion of articles in journals are freely available; in a situation where they lack the funds to purchase all the content their users want [emphasis added] it is inconceivable that they would not seek to save money by cancelling subscriptions to those journals. As a result, those journals will die."First, please note the implicit premise here: Where research institutions 'lack the funds to purchase all the content their researchers want,' the users (researchers) should do without that content, and the providers (researchers) should do without the usage and impact, rather than just giving it to one another, as the RCUK proposes. And why? Because researchers giving their own research to researchers who cannot afford the journal version will make the journals die.

Second, RCUK-funded researchers publish in thousands of journals all over the world -- the UK, Europe and North America. Their publications, though important, represent the output of only a small fraction of the world's research population. Neither research topics nor research journals have national boundaries. Hence it is unlikely that a 'significant proportion' of the articles in any particular journal will become freely available purely as a consequence of the RCUK policy.

Third, journals die and are born every year, since the advent of journals. Their birth may be because of a new niche, and their demise might be because of the loss or saturation of an old niche, or because the new niche was an illusion. Scholarly fashions, emphases and growth regions also change. This is ordinary intellectual evolution plus market economics.

Fourth (and most important), as we have already noted, physics journals already do contain a 'significant proportion' of articles that have been self-archived in the physics repository, arXiv -- yet librarians have not cancelled subscriptions (footnote 1) despite a decade and a half's opportunity to do so, and the journals continue to survive and thrive. So whereas ALPSP may find it subjectively 'inconceivable,' the objective fact is that self-archiving is not generating cancellations, even where it is most advanced and has been going on the longest.

Research libraries -- none of which can afford to subscribe to all journals, because they have only finite journals budgets -- have always tried to maximise their purchasing power, cancelling journals they think their users need less, and subscribing to journals they think their users need more. As objective indicators, some may use (1) usage statistics (paper and online) and (2) citation impact factors, but the final decision is almost always made on the basis of (3) surveys of their own users' recommendations (footnote 2). Self-archiving does not change this one bit, because self-archiving is not done on a per-journal basis but on a per-article basis. And it is done anarchically, distributed across authors, institutions and disciplines. An RCUK mandate for all RCUK-funded researchers to self-archive all their articles will have no net differential effect on any particular journal one way or the other. Nor will RCUK-mandated self-archiving exhaust the contents of any particular journal. So librarians' money-saving and budget-balancing subscription/cancellation efforts may proceed apace. Journals will continue to be born and to die, as they always did, but with no differential influence from self-archiving.

But let us fast-forward this speculation: The RCUK self-archiving mandate itself is unlikely to result in any individual journal's author-archived supplements rising to anywhere near 100%, but if the RCUK model is followed (as is quite likely) by other nations around the world, we may indeed eventually reach 100% self-archiving for all articles in all journals. That would certainly be optimal for research, researchers, their institutions, their funders, and the tax-paying public that funds the funders. Would it be disastrous for journals? A certain amount of pressure would certainly be taken off librarians' endless struggle to balance their finite journal budgets: The yearly journal selection process would no longer be a struggle for basic survival (as all researchers would have online access to at least the author-self-archived supplements), but market competition would continue among publisher-added-values, which include (1) the paper edition and (2) the official, value-added, online edition (functionally enriched with XML mark-up, citation links, publisher's PDF, etc.). The market for those added values would continue to determine what was subscribed to and what was cancelled, pretty much as it does now, but in a stabler way, without the mounting panic and desperation that struggling with balancing researchers' basic inelastic survival needs has been carrying with it for years now (the 'serials crisis').

If, on the other hand, the day were ever to come when there was no longer a market for the paper edition, and no longer a market for some of the online added-values, then surely the market can be trusted to readjust to that new supply/demand optimum, with publishers continuing to sell whatever added values there is still a demand for. One sure added-value, for example, is peer review. Although journals don't actually perform the peer review (researchers do it for them, for free), they do administer it, with qualified expert editors selecting the referees, adjudicating the referee reports, and ensuring that authors revise as required. It is conceivable that one day that peer review service will be sold as a separate service to authors and their insitutions, with the journal-name just a tag that certifies the outcome, instead of being bundled into a product that is sold to users and their institutions. But that is just a matter of speculation right now, when there is still a healthy demand for both the paper and online editions. Publishing will co-evolve naturally with the evolution of the online medium itself. But what cannot be allowed to happen now is for researchers' impact (and the public's investment and stake in it) to be held hostage to the status quo, under the pretext of forestalling a doomsday scenario that has no evidence to support it and all evidence to date contradicting it.

ALPSP: "The consequences of the destruction of journals' viability are very serious. Not only will it become impossible to support the whole process of quality control, including (but not limited to) peer review"Notice that the doomsday scenario has simply been taken for granted here, despite the absence of any actual evidence for it, and despite all the existing evidence to the contrary. Because it is being intoned so shrilly and with such 'conviction', it is to be taken at face value, and we are simply to begin our reckoning with accepting it as an unchallenged premise: but that premise is without any objective foundation whatsoever.

As ALPSP mentions peer review, however, is this not the point to remind ourselves that among the many (unquestionable) values that the publisher does add, peer-review is a rather anomalous one, being an unpaid service that researchers themselves are rendering to the publisher gratis (just as they give their articles gratis, without seeking any payment)?

As noted above, peer review and the certification of its outcome could in principle be sold as a separate service to the author-institution, instead of being bundled with a product to the subscriber-institution; hence it is not true that it would be 'impossible to support' peer review even if journals' subscription base were to collapse entirely. But as there is no evidence of any tendency toward a collapse of the subscription base, this is all just hypothetical speculation at this point.

ALPSP: "but in addition, the research community will lose all the other value and prestige which is added, for both author and reader, through inclusion in a highly rated journal with a clearly understood audience and rich online functionality."Wherever authors and readers value either the paper edition or the rich online functionality -- both provided only by the publisher -- they will continue to subscribe to the journal as long as they can afford it, either personally or through their institutional library. As noted above, this clearly continues to be the case for the physics journals that are the most advanced in testing the waters of self-archiving. Publishers who add sufficient value create a product that the market will pay for (by the definition of supply, demand and sufficient-value). However, surely the interests of research and the public that funds it are not best-served if those researchers (potential users) who happen to be unable to afford the particular journal in which the functionally enriched, value-added version is published are denied access to the basic research finding itself. Even more important and pertinent to the RCUK proposal: The fundee's and funder's research should not be denied the impact potential from all those researchers who cannot afford access.

Researchers have always given away all their findings (to their publishers as well as to all requesters of reprints) so that other researchers could further advance the research by using, applying and building upon their findings. Access-denial has always limited the progress, productivity and impact of science and scholarship. Now the online age has at last made it possible to put an end to this needless access-denial and resultant impact-loss; the RCUK is simply the first to propose systematically applying the natural, optimal, and inevitable remedy to all research output.

Whatever publisher-added value is truly value continues to be of value when it co-exists with author self-archiving. Articles continue to appear in journals, and the enriched functionality of the official value-added online edition (as well as the paper edition) are still there to be purchased. It is just that those who could not afford them previously will no longer be deprived of access to the research findings themselves.

ALPSP: "This in turn will deprive learned societies of an important income stream, without which many will be unable to support their other activities -- such as meetings, bursaries, research funding, public education and patient information -- which are of huge benefit both to their research communities and to the general public."(Notice, first, that this is all still predicated on the truth of the doomsday conviction -- 'that self-archiving will inevitably destroy journals' -- which is contradicted by all existing evidence.)

But insofar as learned-societies 'other activieties' are concerned, there is a very simple, straight-forward way to put the proposition at issue: Does anyone imagine -- if an either/or choice point were ever actually reached, and the trade-off and costs/benefits were made completely explicit and transparent -- that researchers would knowingly and willingly choose to continue subsidising learned societies' admirable good works -- meetings, bursaries, research funding, public education and patient information -- at the cost of their own lost research impact?

The ALPSP doomsday 'conviction', however, has no basis in evidence, hence there is no either/or choice that needs to be made. All indications to date are that learned societies will continue to publish journals -- adding value and successfully selling that added-value -- in peaceful co-existence with RCUK-mandated self-archiving. But entirely apart from that, ALPSP certainly has no grounds for asking researchers to renounce maximising their own research impact for the sake of financing learned societies' good works (like meetings, bursaries and public education) -- good works that could finance themselves in alternative ways that were not parasitic on research progress, if circumstances were ever to demand it

The ALPSP letter began by stating that the mission of ALPSP publisher members is to 'disseminate and maximise access to research information'. Some of the journal-publishing learned societies do indeed affirm that this is their mission; yet by their restrictive publishing practices they actively contradict it, while defending the resulting inescapable contradiction by pleading a disaster scenario (very like the one ALPSP repeatedly invokes) in the name of protecting the publishing profits that support all of the society's other activities. Yet this is not the attitude of forward-thinking, member-oriented societies that understand properly what researchers in their fields need and know how to deliver it. Here is a quote from Dr Elizabeth Marincola, Executive Director of the American Society for Cell Biology, a sizeable but not huge society (10,000 members; many US scientific and medical societies have over 100,000 members):

This perfectly encapsulates why we should not be too credulous about the dire warnings emanating from learned societies to the effect that self-archiving will damage research and its dissemination. The dissemination of research findings should, as avowed, be a high-priority service for societies -- a direct end in itself, not just a trade activity to generate profit so as to subsidise other activities, at the expense of research itself."I think the more dependent societies are on their publications, the farther away they are from the real needs of their members. If they were really doing good work and their members were aware of this, then they wouldn't be so fearful'' When my colleagues come to me and say they couldn't possibly think of putting their publishing revenues at risk, I think 'why haven't you been diversifying your revenue sources all along and why haven't you been diversifying your products all along?' The ASCB offers a diverse range of products so that if publications were at risk financially, we wouldn't lose our membership base because there are lots of other reasons why people are members." (Footnote 3)

ALPSP: "The damaging effects will not be limited to UK-published journals and UK societies; UK research authors publish their work in the most appropriate journals, irrespective of the journals' country of origin."The thrust of the above statement is rather unclear: The RCUK-mandated self-archiving itself will indeed be distributed across all journals, worldwide. Hence, if it had indeed been 'damaging', that damage would likewise be distributed (and diluted) across all journals, not concentrated on any particular journal. So what is the point being made here?

But in fact there is no evidence at all that self-archiving is damaging to journals, rather than co-existing peacefully with them; and a great deal of evidence that it is extremely beneficial to research, researchers, their institutions and their funders.

ALPSP: "We absolutely reject unsupported assertions that self-archiving in publicly accessible repositories does not and will not damage journals. Indeed, we are accumulating a growing body of evidence that the opposite is the case [emphasis added], even at this early stage"We shall now examine whose assertions need to be absolutely rejected as unsupported, and whether there is indeed 'a growing body of evidence that the opposite is the case'.

What follows is the ALPSP's 5 pieces of putative evidence in support of their expressed 'conviction' that self-archiving will damage journals. Please follow carefully, as the first two pieces of evidence [1]-[2] -- concerning usage and citation statistics -- will turn out to be positive evidence rather than negative evidence, and the last three pieces of evidence [3]-[5] -- concerning journals that make all of their own articles free online -- turn out to have nothing whatsoever to do with author self-archiving:

ALPSP: "For example:How does example [1] show that 'the opposite is the case'? As has already been reported above, the Institute of Physics Publishing (UK) and the American Physical Society (US) have both stated publicly that they can identify no loss of subscriptions as a result of nearly 15 years of self-archiving by physicists! (Moreover, publishers and institutional repositories can and will easily work out a collaborative system of pooled usage statistics, all credited to the publisher's official version; so that is no principled obstacle either.)

[1] Increasingly, librarians are making use of COUNTER-compliant (and therefore comparable) usage statistics to guide their decisions to renew or cancel journals. The Institute of Physics Publishing is therefore concerned to see that article downloads from its site are significantly lower for those journals whose content is substantially replicated in the ArXiV repository than for those which are not."

The easiest thing in the world for Institutional Repositories (IRs) to provide to publishers (along with the link from the self-archived supplement in the IR to the official journal version on the publisher's website -- something that is already dictated by good scholarly practice) is the IR download statistics for the self-archived version of each article. These can be pooled with the download statistics for the official journal version and all of it (rightly) credited to the article itself. Another bonus that the self-archived supplements already provide is enhanced citation impact -- of which it is not only the article, the author, the institution and the funder who are the co-beneficiaries, but also the journal and the publisher, in the form of an enhanced journal impact factor (average citation count). It has also been demonstrated recently that download impact and citation impact are correlated, downloads in the first six months after publication being predictive of citations after 2 years.

All these statistics and benefits are there to be shared between publishers, librarians and research institutions in a cooperative, collaborative atmosphere that welcomes the benefits of self-archiving to research and that works to establish a system that shares them among the interested parties. Collaboration on the sharing of the benefits of self-archiving is what learned societies should be setting up meetings to do -- rather than just trying to delay and oppose what is so obviously a substantial and certain benefit to research, researchers, their institutions and funders, as well as a considerable potential benefit to journals, publishers and libraries. If publishers take an adversarial stance on self-archiving, all they do is deny themselves of its potential benefits (out of the groundless but self-sustaining 'conviction' that self-archiving can inevitably bring them only disaster). Its benefits to research are demonstrated and incontestable, hence will incontestably prevail. (ALPSP's efforts to delay the optimal and inevitable will not redound to learned societies' historic credit; the sooner they drop their filibustering and turn to constructive cooperation and collaboration, the better for all parties concerned.)

ALPSP: "[2] Citation statistics and the resultant impact factors are of enormous importance to authors and their institutions; they also influence librarians' renewal/cancellation decisions. Both the Institute of Physics and the London Mathematical Society are therefore troubled to note an increasing tendency for authors to cite only the repository version of an article, without mentioning the journal in which it was later published."Librarians' decisions about which journals to renew or cancel take into account a variety of comparative measures, citation statistics being one of them (footnote 2). Self-archiving has now been analysed extensively and shown to increase journal article citations substantially in field after field; so journals carrying self-archived articles will have higher impact factors, and will hence perform better under this measure in competing for their share of libraries' serials budgets. This refutes example [2].

As to the proper citation of the official journal version: This is merely a question of proper scholarly practice, which is evolving and will of course adapt naturally to the new medium; a momentary lag in scholarly rigour is certainly no argument against the practice of self-archiving or its benefits to research and researchers. Moreover, publishers and institutional repositories can and will easily work out a collaborative system of pooled citation and reference statistics -- all credited to the official published version. So that is no principled obstacle either. This is all just a matter of adapting scholarly practices naturally to the new medium (and is likewise inevitable). It borders on the absurd to cite something whose solution is so simple and obvious as serious grounds for preventing research impact from being maximised by universal self-archiving!

ALPSP: "[3] Evidence is also growing that free availability of content has a very rapid negative effect on subscriptions. Oxford University Press made the contents of Nucleic Acids Research freely available online six months after publication; subscription loss was much greater than in related journals where the content was free after a year. The journal became fully Open Access this year, but offered a substantial reduction in the publication charge to those whose libraries maintained a print subscription; however, the drop in subscriptions has been far more marked than was anticipated."This is a non-sequitur, having nothing to do with self-archiving, one way or the other (as was already pointed out in the prior rebuttal of APLSP's April critique of the RCUK proposal): This example refers to an entire journal's contents -- the official value-added versions, all being made freely accessible, all at once, by the publisher -- not to the anarchic, article-by-article self-archiving of the author's final draft by the author, which is what the RCUK is mandating. This example in fact reinforces what was noted earlier: that RCUK-mandated self-archiving does not single out any individual journal (as OU Press did above with one of its own) and drive its self-archived content to 100%. Self-archiving is distributed randomly across all journals. Since journals compete (somewhat) with one another for their share of each institution's finite journal acquisitions budget, it is conceivable that if one journal gives away 100% of its official, value-added contents online and the others don't, that journal might be making itself more vulnerable to differential cancellation (though not necessarily: there are reported examples of the exact opposite effect too, with the free online version increasing not only visibility, usage and citations, but thereby also increasing subscriptions, serving as an advertisement for the journal). But this is in any case no evidence for cancellation-inducing effects of self-archiving, which involves only the author's final drafts and is not focussed on any one journal but randomly distributed across all journals, leaving them to continue to compete for subscriptions amongst themselves, on the basis of their relative merits, exactly as they did before.

ALPSP: "[4] The BMJ Publishing Group has noted a similar effect; the journals that have been made freely available online on publication have suffered greatly increased subscription attrition, and access controls have had to be imposed to ensure the survival of these titles."Exactly the same reply as above: The risks of making 100% of one journal's official, value-added contents free online while all other journals are not doing likewise has nothing whatosever to do with anarchic self-archiving, by authors, of the final drafts of their own articles, distributed randomly across journals.

ALPSP: "[5] In the USA, the Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences found that two of its journals had, without its knowledge, been made freely available on the Web. For one of these, an established journal, they noted a subscriptions decline which was more than twice as steep as the average for their other established journals; for the other, a new journal where subscriptions would normally have been growing, they declined significantly. While the unauthorised free versions have now been removed, it is too early to tell whether the damage is permanent."Exactly the same artifact as in the prior two cases. (The trouble with self-generated Doomsday Scenarios is that they tend to assume such a grip on the imagination that their propounders cannot distinguish objective evidence from the 'corroboration' that comes from merely begging the question or changing the subject!)