Friday, July 17. 2009

OA in High Energy Physics Arxiv Yields Five-Fold Citation Advantage

SUMMARY: Evidence confirming that OA increases impact will not be sufficient to induce enough researchers to provide OA; only mandates from their institutions and funders can ensure that. HEP researchers continue to submit their papers to peer-reviewed journals, as they always did, depositing both their unrefereed preprints and their refereed postprints. None of that has changed. In fields like HEP and astrophysics, the journal affordability/accessibility problem is not as great as in many other fields, where it the HEP Early Access impact advantage translates into the OA impact advantage itself. Almost no one has ever argued that Gold OA provides a greater OA advantage than Green OA.The OA advantage is the OA advantage, whether Green or Gold.

Update Jan 1, 2010: See Gargouri, Y; C Hajjem, V Larivière, Y Gingras, L Carr,T Brody & S Harnad (2010) “Open Access, Whether Self-Selected or Mandated, Increases Citation Impact, Especially for Higher Quality Research”

Update Feb 8, 2010: See also "Open Access: Self-Selected, Mandated & Random; Answers & Questions"

Gentil-Beccot, Anne; Salvatore Mele, Travis Brooks (2009) Citing and Reading Behaviours in High-Energy Physics: How a Community Stopped Worrying about Journals and Learned to Love Repositories

EXCERPTS: from Gentil-Beccot et al:

This is an important study, and most of its conclusions are valid:(1) Making research papers open access (OA) dramatically increases their impact.However, the following caveats need to be borne in mind, in interpreting this paper:

(2) The earlier that papers are made OA, the greater their impact.

(3) High Energy Physics (HEP) researchers were among the first to make their papers OA (since 1991, and they did it without needing to be mandated to do it!)

(4) Gold OA provides no further impact advantage over and above Green OA.

(a) HEP researchers have indeed been providing OA since 1991, unmandated (and computer scientists have been doing so since even earlier). But in the ensuing years, the only other discipline that has followed suit, unmandated, has been economics, despite the repeated demonstration of the Green OA impact advantage across all disciplines. So whereas still further evidence (as in this paper by Gentil-Beccot et al) confirming that OA increases impact is always very welcome, that evidence will not be sufficient to induce enough researchers to provide OA; only mandates from their institutions and funders can ensure that they do so.

(b) From the fact that when there is a Green OA version available, users prefer to consult that Green OA version rather than the journal version, it definitely does not follow that journals are no longer necessary. Journals are (and always were) essentially peer-review service-providers and cerifiers, and they still are. That essential function is indispensable. HEP researchers continue to submit their papers to peer-reviewed journals, as they always did; and they deposit both their unrefereed preprints and then their refereed postprints in arxiv (along with the journal reference). None of that has changed one bit.

(c) Although it has not been systematically demonstrated, it is likely that in fields like HEP and astrophysics, the journal affordability/accessibility problem is not as great as in many other fields. OA's most important function is to provide immediate access to those who cannot afford access to the journal version. Hence the Early Access impact advantage in HEP -- arising from making preprints OA well before the published version is available -- translates, in the case of most other fields, into the OA impact advantage itself, because without OA many potential users simply do not have access even after publication, hence cannot make any contribution to the article's impact.

(d) Almost no one has ever argued (let alone adduced evidence) that Gold OA provides a greater OA advantage than Green OA. The OA advantage is the OA advantage, whether Green or Gold. (It just happens to be easier and more rigorous to test and demonstrate the OA advantage through within-journal comparisons [i.e Green vs. non-Green articles] than between-journal comparisons [Gold vs. non-Gold journals].)Stevan Harnad

ABSTRACT: Contemporary scholarly discourse follows many alternative routes in addition to the three-century old tradition of publication in peer-reviewed journals. The field of High- Energy Physics (HEP) has explored alternative communication strategies for decades, initially via the mass mailing of paper copies of preliminary manuscripts, then via the inception of the first online repositories and digital libraries.

This field is uniquely placed to answer recurrent questions raised by the current trends in scholarly communication: is there an advantage for scientists to make their work available through repositories, often in preliminary form? Is there an advantage to publishing in Open Access journals? Do scientists still read journals or do they use digital repositories?

The analysis of citation data demonstrates that free and immediate online dissemination of preprints creates an immense citation advantage in HEP, whereas publication in Open Access journals presents no discernible advantage. In addition, the analysis of clickstreams in the leading digital library of the field shows that HEP scientists seldom read journals, preferring preprints instead....

...

...arXiv was first based on e-mail and then on the web, becoming the first repository and the first “green” Open Access5 platform... With the term “green” Open Access we denote the free online availability of scholarly publications in a repository. In the case of HEP, the submission to these repositories, typically arXiv, is not mandated by universities or funding agencies, but is a free choice of authors seeking peer recognition and visibility... The results of an analysis of SPIRES data on the citation behaviour of HEP scientists is presented... demonstrat[e] the “green” Open Access advantage in HEP... With the term “gold” Open Access we denote the free online availability of a scholarly publication on the web site of a scientific journals.... There is no discernable citation advantage added by publishing articles in “gold” Open Access journals...

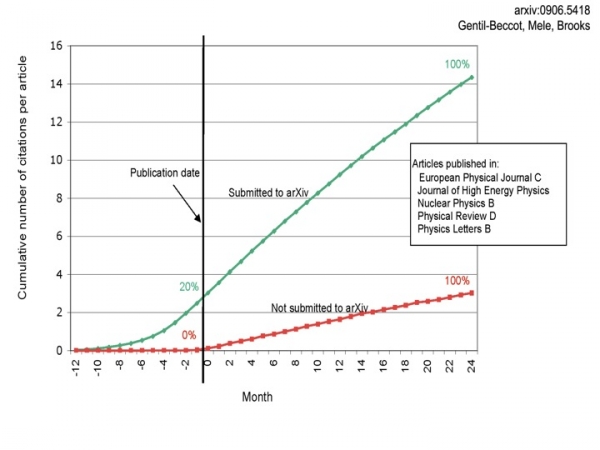

Figure (Gentil-Beccot et al. 2009): Cumulative citation count as a function of the age of the paper relative to its publication date. 4839 articles from 5 major HEP journals published in 2005 are considered....

7. Conclusions

Scholarly communication is at a cross road of new technologies and publishing models. The analysis of almost two decades of use of preprints and repositories in the HEP community provides unique evidence to inform the Open Access debate, through four main findings:

1. Submission of articles to an Open Access subject repository, arXiv, yields a citation advantage of a factor five.

2. The citation advantage of articles appearing in a repository is connected to their dissemination prior to publication, 20% of citations of HEP articles over a two-year period occur before publication.

3. There is no discernable citation advantage added by publishing articles in “gold” Open Access journals.

4. HEP scientists are between four and eight times more likely to download an article in its preprint form from arXiv rather than its final published version on a journal web site.

Taken together these findings lead to three general conclusions about scholarly communication in HEP, as a discipline that has long embraced green Open Access:

1. There is an immense advantage for individual authors, and for the discipline as a whole, in free and immediate circulation of ideas, resulting in a faster scientific discourse.

2. The advantages of Open Access in HEP come without mandates and without debates. Universal adoption of Open Access follows from the immediate benefits for authors.

3. Peer-reviewed journals have lost their role as a means of scientific discourse, which has effectively moved to the discipline repository.

HEP has charted the way for a possible future in scholarly communication to the full benefit of scientists, away from over three centuries of tradition centred on scientific journals. However, HEP peer-reviewed journals play an indispensable role, providing independent accreditation, which is necessary in this field as in the entire, global, academic community. The next challenge for scholarly communication in HEP, and for other disciplines embracing Open Access, will be to address this novel conundrum. Efforts in this direction have already started, with initiatives such as SCOAP3...

Sunday, July 5. 2009

Beyond Romary & Armbruster On Institutional Repositories

Critique of: Romary, L & Armbruster, C. (2009) Beyond Institutional Repositories.

R&A: "The current system of so-called institutional repositories, even if it has been a sensible response at an earlier stage, may not answer the needs of the scholarly community, scientific communication and accompanied stakeholders in a sustainable way."Almost all institutional repositories today are near-empty. Until and unless they are successfully filled with their target content, talk about their "answering needs" or being made "sustainable" is moot.

The primary target content of both the Open Access movement and the Institutional (and Central) Repository movement is refereed research: the 2.5 million articles per year published in the planet's 25,000 peer-reviewed journals. (That is why R&C speak, rather ambiguously, about "Publication Repositories.")

Institutions are the universal providers of all that refereed research output, funded and unfunded, in all scholarly and scientific disciplines, worldwide.

Institutions have a fundamental interest in hosting, inventorying, monitoring, managing, assessing, and showcasing their own research output, as well as in maximizing its uptake, usage and impact.

Yet not only is most of the research output of most institutions failing to be deposited in the institution's own repository: most of it is not being deposited in any other repository either. (Please keep this crucial fact in mind as you reflect on the critique below.)

R&A: "[H]aving a robust repository infrastructure is essential to academic work."A repository, be its "infrastructure" as "robust" as you like, is of no use for academic work as long as it is near-empty.

R&A: "[C]urrent institutional solutions, even when networked in a country or across Europe, have largely failed to deliver."Largely empty repositories, "networked" to largely empty repositories remain doomed to deliver next to nothing.

R&A: "Consequently, a new path for a more robust infrastructure and larger repositories is explored to create superior services that support the academy."Making largely empty repositories "larger" (by "networking" them) is as futile as "making their infrastructure more robust": What repositories lack and need is their target content.

The reason most repositories are near-empty is that most researchers are not depositing in them.

And the reasons most researchers are not depositing are multiple (there are at least 34 of them), but they boil down to one basic reason, and researchers have already indicated, clearly, in international surveys, what that one basic reason is: Deposit has not been mandated (by their institutions or their funders).

Ninety-five percent of researchers surveyed across all disciplines, worldwide, most of whom do not deposit, respond that they would deposit if deposit were mandated, 14% of them reluctantly, and 81% of them willingly. (Swan)

And outcome studies have shown that researchers do what they said they would do: When deposit is mandated, they do indeed deposit, in high proportions, within two years of adoption of the deposit mandate. (Sale)

Hence what institutions need in order to induce their researchers to deposit is not larger or more robust repositories, but deposit mandates.

The number of mandates is growing, but there are still as yet only 90 of them worldwide.

Hence what is urgently needed to fill repositories so they can begin providing "superior services" for the academy is more mandates, not larger repositories or "more robust infrastructure."

R&A: "[F]uture organisation of publication repositories is advocated that is based upon macroscopic academic settings providing a critical mass of interest as well as organisational coherence."The only "critical mass" that repositories need is their missing target OA content.

Researchers have an intrinsic interest in making their research output OA. Institutions have an interest in making their research OA. Funders have an interest in making their research output OA. And the tax-paying public has an interest in making the research they fund OA.

In contrast, subscription/license publishers do not have an intrinsic interest in making the research they publish OA except if they are paid for it (via Gold OA publication fees). Publishers view Green OA (via repository deposit) as putting their subscription and license revenues at risk. They haven't much choice but to endorse deposit by their authors, given the research benefits of OA, and particularly when it is mandated by their authors' institutions and funders; but publishers themselves certainly have no need or desire to do the depositing on their authors' behalf, for free.

The way to see this clearly is to realize that Green OA amounts to repository deposit by authors, for free, whereas Gold OA amounts to "repository deposit" by publishers, for a fee.

Most publishers are not depositing today because they are not being paid to do it.

Most authors are not depositing today because they are not being mandated to do it.

There is no solution in "amalgamating" these respective empty repositories (unmandated Green and unpaid Gold). The solution is either more mandates or more money.

As subscriptions/licenses are covering the costs of publication today, there is neither the need to pay for Gold OA, pre-emptively, today nor the extra money to pay for it: The potential money is tied up in paying the subscription/license fees that are already covering the costs of publication.

Mandates do not depend on publishers but on institutions and funders; nor do mandates bind publishers: they bind only authors. It is hence incoherent to imagine macro-repositories fed by both authors and publishers. Nor is it necessary, since institutional (and funder) deposit mandates, along with institutional repositories are jointly necessary and sufficient to achieve 100% OA.

R&A: "Such a macro-unit may be geographical (a coherent national scheme), institutional (a large research organisation or a consortium thereof) or thematic (a specific research field organising itself in the domain of publication repositories).""Macro" organisations -- whether institutional consortia, national consortia or disciplinary consortia -- do not resolve this fundamental contradiction between free access and any scheme to pay for access.

(In principle, McDonalds and Burger King could give free access to hamburgers if a global consortium of some sort were to agree to bankroll it all up-front; however, that would hardly be free access: it would simply be global acquiescence to a global oligopoly on the sale of a product.)

So forget about counting on publishers to deposit articles in OA repositories -- whether institutional or central -- unless they are paid up-front to do so. And paying them to do so via licenses is not "organisational coherence" but what biologists would call an "evolutionarily unstable strategy," doomed to collapse because of its own intrinsic instability.

It is the articles' authors who need to deposit, and it is that deposit that their institutions and funders need to mandate.

R&A: "The argument proceeds as follows: firstly, while institutional open access mandates have brought some content into open access, the important mandates are those of the funders"This "argument" is demonstrably incorrect.

Not all or even most of research is funded, whereas all research originates from institutions. Hence institutional mandates cover all research, whereas funder mandates cover only funded research.

The NIH, RCUK and ERC funder mandates were indeed important because they set an example for other funders to follow (and many are indeed following); but that still only covers funded research. Funder mandates do not scale up to cover all research.

The Harvard, Stanford and MIT institutional mandates were hence far more important, because they set an example for other institutions to follow (and many are indeed following); and this does cover all research output, because institutions are the universal providers of all research output, whether funded or unfunded, across all disciplines.

R&A: "[Funder mandates] are best supported by a single infrastructure and large repositories, which incidentally enhances the value of the collection (while a transfer to institutional repositories would diminish the value)."This is again profoundly incorrect. The only "value enhancement" that empty collections need is their missing content. (Nor are we talking about "transfer" yet, since the target contents are not being deposited. We are talking about mandating deposit.)

Funder mandates can be fulfilled just as readily by depositing in institutional repositories or central ones. Repository size and locus of deposit are completely irrelevant. All OAI-compliant repositories are interoperable. The OAI-PMH allows central harvesting from distributed repositories. In addition, transfer protocols like SWORD allow direct, automatic repository-to-repository transfer of contents.

Hence there is no functional advantage whatsoever to direct central deposit, since central harvesting from institutional repositories achieves exactly the same functional result. Instead, direct central deposit mandates have the great disadvantage that they compete with institutional mandates instead of facilitating them.

Both the natural and the optimal locus of deposit is the institutional repository, for both institutions and funders. That way funder mandates and institutional mandates collaborate and converge, covering all research output.

And now an important correction of a widespread misinterpretation of the relative success of institutional and central repositories in capturing their target content:Summary:

(1) Repository size and "infrastructure" do not generate content.

(2) Empty repositories are useless.

(3) The only way to fill them is to mandate deposit.

(4) Not all or most research is funded.

(5) But all research originates from institutions.

(6) Institutions' interests are served by hosting and managing their own research assets.

(7) Hence both institutional and funder mandates should converge on institutional deposit.

(8) Any central collections can then be harvested from the global distributed of institutional repositories.

The Denominator Fallacy. With one prominent exception -- which has absolutely nothing to do with the fact that the exceptional repository in question, the physics Arxiv, happens to be central rather than institutional -- unmandated central repositories (and there are many) are no more successful in getting themselves filled with their target content than unmandated institutional repositories. The critical causal variable is the mandate, not the repository's centrality or size.

The way to arrive at a clear understanding of this fundamental fact is to note that the denominator -- i.e., the total target content relative to which we are trying to reckon, for a given repository, what proportion of it is being deposited -- is far bigger for a central disciplinary repository than for an institutional repository.

For an institutional repository, its denominator is the total number of refereed journal articles, across all disciplines, produced by that institution annually.

For a central disciplinary repository, its denominator is the total number of refereed journal articles, across all institutions worldwide, published in that discipline annually. (For a national repository, like HAL, its denominator is the total research output of all the nation's institutions, across all disciplines.)

So it is no wonder that central repositories are "larger" than institutional ones: Their total target content is much larger. But this difference in absolute size is not only irrelevant but deeply misleading. For the proportion of their total annual target content that unmandated central repositories are actually capturing is every bit as minuscule as the proportion that unmandated institutional repositories are capturing. And whereas the total size of a mandated institutional repository remains much smaller than an unmandated central repository, the reality is that the mandated institutional repositories are capturing (or near capturing) their total target outputs, whereas the unmandated central repositories are far from capturing theirs.

The reason Arxiv is a special case is not at all because it is a central repository but because the physicists that immediately began depositing in Arxiv way back in 1991, with no need whatsoever of a mandate to impel them to do so, had already long been doing much the same thing in paper (at the CERN and SLAC paper depositories), and necessarily centrally, because in the paper medium there is no way one can send one's paper to "everyone," nor to get everyone to access or "harvest" each new paper from each author's own institutional depository (if there had been such a thing).

All of that is over now. And if physicists had made the transition from paper preprint deposit to online preprint deposit directly today rather than in 1991, in the OAI-MPH era of repository interoperability and harvesting, there is no doubt that they would have deposited in their own respective institutional repositories and CERN and SLAC and Arxiv would simply have harvested the metadata automatically from there (with the obvious computational alerting mechanisms set up for harvesting, export and import).

But that longstanding cultural practice of preprint deposit among physicists would be just as anomalous if physicists had begun it all by depositing institutionally rather than centrally, for no other (unmandated) central repository (or discipline) is capturing the high portion of its annual total target content that the physics Arxiv is capturing (in certain preprint-sharing subfields of physics) and has been capturing ever since since 1991, in the absence of any deposit mandate.

So the centrality, size and success of Arxiv is completely irrelevant to the problem of how to fill all other unmandated repositories, whether central or institutional, large or small, in any other discipline, and regardless of the "robustness" of the repository's "infrastructure." Only the mandated repositories are successfully capturing their target content, and there is no longer any need to deposit directly in central repositories: In the OAI-compliant OA era, central "repositories" need only be collections, harvested from the distributed local repositories of the universal research providers: the institutions.

R&A: "Secondly, we compare and contrast a system based on central research publication repositories with the notion of a network of institutional repositories to illustrate that across central dimensions of any repository solution the institutional model is more cumbersome and less likely to achieve a high level of service."The assumption is made here -- with absolutely no supporting evidence, and with all existing evidence (other than the single special case of Arxiv, discussed above) flatly contradicting it -- that researchers are more likely to deposit their refereed journal articles in big central repositories than in their own institutional repositories.

All evidence is that researchers are equally unlikely to deposit in either kind of repository unless deposit is mandated, in which case it makes no difference whether the repository is institutional or central -- except that if both funders and institutions mandate institutional deposit then their mandates converge and reinforce one another, whereas if funders mandate central deposit and institutions mandate institutional deposit then their mandates diverge and compete with one another.

(And of course the natural direction for harvesting is from local to central, not vice versa: We all deposit on our institutional websites and google harvests from there; it would be absurd for everyone to deposit in google and then back-harvest to their own institutional website. The same is true for any central OAI harvesting service.)

R&A: "Next, three key functions of publication repositories are reconsidered, namely a) the fast and wide dissemination of results; b) the preservation of the record; and c) digital curation for dissemination and preservation."Again, these functions in no way distinguish central and institutional repositories (both can and do provide them) and have no bearing whatsoever on the real problem, which is the absence of the target content -- for which the remedy is to mandate deposit. Otherwise there's nothing to curate, preserve and disseminate.

R&A: "Fourth, repositories and their ecologies are explored with the overriding aim of enhancing content and enhancing usage."You cannot enhance content if the content is not there. And you cannot enhance the usage of absent content. Hence it is it not enhancements that are needed but deposit mandates to generate the nonexistent content for which all these enhancements are being contemplated...

R&A: "Fifth, a target scheme is sketched, including some examples."The target scheme includes a suggestion that publishers should do the depositing, of their own proprietary version of the refereed article. This is perhaps the worst suggestion of all. Just when institutions are at last realizing that after decades of outsourcing it to publishers, they can now host and manage their own research output by mandating that their researchers deposit their final refereed drafts in their own institutional repositories, Romary & Armbruster instead suggest "consolidated" central "publication repositories" in which publishers do the depositing. (The question to contemplate is: If it requires a mandate to induce researchers to deposit, what will it require to induce publishers to deposit -- other than paying them to do it? And if so, who will pay how much for what, out of what money -- and why?)

Most of the rest of R&C's suggestions are superfluous, and fail completely to address the real problem: the absence of OA's target content. You can't go "beyond" institutional repositories until you first succeed in filling them.

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Saturday, July 4. 2009

What's in a Word? To "Legislate" and/or to "Legitimize": the Double-Meaning of (Open Access) "Mandate"

SUMMARY: Stuart Shieber is right in his reflections on the word "mandate," which is only useful if it helps get a deposit policy adopted and complied with. Author surveys and outcome studies show that most authors comply with self-archiving mandates willingly, so why do they need a mandate at all? Authors worry that self-archiving (1) is illegal, (2) puts acceptance for publication at risk and (3) and is time-consuming. Because it means both "legislate" and "legitimize," a "mandate" alleviates (1) - (3) by making self-archiving an official institutional requirement. Mandates need to ensure that authors deposit their final refereed drafts upon acceptance for publication whether or not they opt out of making access to their deposits immediately Open Access. The option of Closed Access deposit moots worries about legality or journal prejudice, making deposit merely an institution-internal record-keeping matter. But there is still a big difference between a request and a requirement. The failure of the first version of the NIH policy (merely a request) has shown that only an official requirement can generate deposits and fill repositories. There need be no penalties for noncompliance. Citations count, and OA enhances citations. Hence making one's research output OA is already connected causally to the existing "publish-or-perish" reward system of academia. A number of mandating institutions have accordingly coupled their deposit mandates procedurally to their performance review system: Faculty already have to submit their refereed publication lists for performance review today, so the only other thing needed is an administrative notice that henceforth the official mode of submission of publications for performance review will be via deposit in the Institutional Repository.

What's in a word? Although there is a hint of the hermeneutic in his reflections on the uses of the word "mandate," I think Stuart Shieber, the architect of Harvard's historic Open Access (OA) policy is quite right in spirit. The word "mandate" is only useful to the extent that it helps get a deposit policy officially adopted -- and one that most faculty will actually comply with.

What's in a word? Although there is a hint of the hermeneutic in his reflections on the uses of the word "mandate," I think Stuart Shieber, the architect of Harvard's historic Open Access (OA) policy is quite right in spirit. The word "mandate" is only useful to the extent that it helps get a deposit policy officially adopted -- and one that most faculty will actually comply with.Carrots not sticks. First, note that it has never been suggested that there need to be penalties for noncompliance. OA, after all, is based solely on benefits to the researcher; the idea is not to coerce researchers into doing something that is not in their interest, or something they would really prefer not to do.

Authors are willing. Indeed, the author surveys and outcome studies that I have so often cited provide evidence that -- far from being opposed to deposit mandates -- authors welcome them, and comply with them, over 80% of them willingly.

So why bother mandating? It is hence natural to ask: if researchers welcome and willingly comply with deposit mandates, why don't they deposit without a mandate?

To legitimize by legislating. I think this is a fundamental question; that it has an answer; and that its answer is very revealing and especially relevant here, because it is related to the double meaning of "mandate", which means both to "legislate" and to "legitimize":

Alleviating worries. There are many worries (at least 34 of them, all groundless and easily answered) keeping most authors from self-archiving on their own, unmandated. But the principle three are worries (1) that self-archiving is illegal, (2) that self-archiving may put acceptance for publication by their preferred journals at risk and (3) that self-archiving is a time-consuming, low-priority task for already overloaded academics. Formal institutional mandates to self-archive alleviate worries (1) - (3) (and the 31 lesser worries as well) by making it clear to all that self-archiving is now an official institutional policy of high priority.

Opt-outs. Harvard's mandate alleviates the three worries (although not, in my opinion, in the optimal way) by (1) mandating rights-retention, but (2) allowing a waiver or opt-out if the author has any reason not to comply. This covers legal worries about copyright and practical worries about publisher prejudice. The ergonomic worry is mooted by (3) having a proxy service (from the provost's office, not the dean's!) do the deposit on the author's behalf.

Optimality. The reason I say the Harvard mandate is not optimal is that -- as Stuart notes -- the crucial condition for the success and universality of OA self-archiving mandates is to ensure that the deposit itself gets done, under all conditions, even if the author opts out because of worries about legality or publisher prejudice.

Deposit in any case. This distinction is clearly made in the FAQ accompanying the Harvard mandate, informing authors that they should deposit their final refereed drafts upon acceptance for publication whether or not they opt out of making access to their deposits immediately OA.

Institutional record-keeping. Hence it is Harvard's mandate itself (not just the accompanying FAQ) that should require immediate deposit; and the opt-out clause should only pertain to whether or not access to that mandatory deposit is immediately made OA. The reason is that Closed Access deposit moots both the worry about legality and the worry about journal prejudice. It is merely an institution-internal record-keeping matter, not an OA or publication issue.

After the FAQ. But even though the Harvard mandate in its current form is suboptimal in this regard, this probably does not matter greatly, because the combination of Harvard's official mandate and Harvard's accompanying FAQ have almost the same effect as including the deposit requirement in the official mandate would have had. The mandate is in any case noncoercive. There are no penalties for noncompliance. It merely provides Harvard's official institutional sanction for self-archiving and it officially enjoins all faculty to do so. (Note that both "injunction" and "sanction" likewise have the double-meaning of "mandate": each can mean either officially legislating something or officially legitimizing something, or both.)

Lesson from NIH. Now to something closer to ordinary English: There is definitely a difference between an official request and an official requirement; and the total failure of the first version of the NIH policy (merely a request) -- as well as the persistent failure of the current request-policies of all the nonmandatory institutional repositories to date -- has confirmed that only an official requirement can successfully generate deposits and fill repositories -- as the subsequent NIH policy upgrade to a mandate and the 90 other institutional and funder mandates worldwide are demonstrating.

Requirements work, requests don't. So whereas the word "mandate" (or "requirement") may sometimes be a handicap at the stage where an institution is still debating about whether or not to adopt a deposit policy at all, it is definitely an advantage, indeed a necessity, if the policy, once adopted, is to succeed in generating compliance: Requirements work, requests don't.

No penalties for noncompliance. All experience to date has also shown that whereas adding various positive incentives (rewards for first depositors, "cream of science" showcasing, librarian assistance and proxy-depositing) to a mandate can help accelerate compliance, no penalties for noncompliance are needed. Mandates work if they are officially requirements and not requests, if compliance monitoring and implementation procedures are in place, and if the researcher population is well informed of both the mandate requirements and the benefits of OA.

"Publish-or-perish." Having said all that, I would like to close by pointing out one sanction/incentive (depending on how you look at it) that is already implicitly built into the academic reward system: Is "publish-or-perish" a mandate, or merely an admonition?

Research impact. Academics are not "required" to publish, but they are well-advised to do so, for success in getting a job, a grant, or a promotion. Nor are publications merely counted any more, in performance review, like beans. Their research impact is taken into account too. And it is precisely research impact that OA enhances.

Performance review. So making one's research output OA is already connected causally to the existing "publish-or-perish" reward system of academia, whether or not OA is mandated. An OA mandate simply closes the causal loop and makes the causal connection explicit. Indeed, a number of the mandating institutions have procedurally linked their deposit mandates to their performance review system as follows:

Submission format. Faculty just about everywhere already have to submit their refereed publication lists for performance review today. Several of the universities that mandate deposit have simply updated their submission procedure such that henceforth the official mode of submission of publications for performance review will be via deposit in the Institutional Repository.

"Online or invisible." This simple, natural procedural update -- not unlike the transition from submitting paper CVs to submitting digital CVs -- is at the same time all the sanction/incentive that academics need: To borrow the title of Steve Lawrence's seminal 2001 Nature paper on the OA impact advantage: "Online or Invisible."

Keystroke mandate. Hence an OA "mandate" is in essence just another bureaucratic requirement to do a few extra keystrokes per paper, to deposit a digital copy in one's institution's IR. This amounts to no more than a trivial extension to academia's existing "mandate" to do the keystrokes to write and publish the paper in the first place: Publish or Perish, Deposit to Flourish.

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Friday, July 3. 2009

Australia's 8th Green OA Mandate: Victoria University

ROARMAP (Registry of Open Access Repository Material Archiving Policies)

Institution's OA Self-Archiving Mandate:

Authors of material which represents publicly available research and scholarly output of the University must ensure its submission to the University's Institutional repository, subject to the exclusions noted.

The following materials are to be included:

Register your Institutional Policy in ROARMAP

Register your Institutional Repository in ROAR

Victoria University (AUSTRALIA institutional-mandate)

Institution's OA Repository

Institution's OA Self-Archiving Mandate:

Authors of material which represents publicly available research and scholarly output of the University must ensure its submission to the University's Institutional repository, subject to the exclusions noted.

The following materials are to be included:

• Refereed scholarly and research articles and contributions by current VU staff and students at the post-print stage (subject to any necessary agreement with the publisher)

• Refereed scholarly and research literature by current VU staff and students at the pre-print stage (with corrigenda added subsequently if necessary at the discretion of the author)

• PhD and Masters by Research degree theses by VU students

• University related research material such as books, working papers, discussion papers, government submissions, reports and inaugural professorial lectures

« previous page

(Page 2 of 2, totaling 14 entries)

EnablingOpenScholarship (EOS)

Quicksearch

Syndicate This Blog

Materials You Are Invited To Use To Promote OA Self-Archiving:

Videos:

audio WOS

Wizards of OA -

audio U Indiana

Scientometrics -

The American Scientist Open Access Forum has been chronicling and often directing the course of progress in providing Open Access to Universities' Peer-Reviewed Research Articles since its inception in the US in 1998 by the American Scientist, published by the Sigma Xi Society.

The American Scientist Open Access Forum has been chronicling and often directing the course of progress in providing Open Access to Universities' Peer-Reviewed Research Articles since its inception in the US in 1998 by the American Scientist, published by the Sigma Xi Society.

The Forum is largely for policy-makers at universities, research institutions and research funding agencies worldwide who are interested in institutional Open Acess Provision policy. (It is not a general discussion group for serials, pricing or publishing issues: it is specifically focussed on institutional Open Acess policy.)

You can sign on to the Forum here.

Archives

Calendar

Categories

Blog Administration

Statistics

Last entry: 2018-09-14 13:27

1129 entries written

238 comments have been made