Joseph Esposito [JE]

Joseph Esposito [JE] asks, in liblicense-l:

JE: “What happens when the number of author-pays open access sites grows and these various services have to compete with one another to get the finest articles deposited in their respositories?”

Green OA mandates require deposit in each author's own institutional repository. The hypothesis of Post-Green-OA subscription cancellations (which is only a hypothesis, though I think it will eventually prove to be right) is that the Green OA version will prove to be enough for users, leaving peer review as the only remaining essential publishing service a journal will need to perform.

Whether on the non-OA subscription model or on the Gold-OA author-pays model, the only way scholarly/scientific journals compete for content is through their peer-review standards: The higher-quality journals are the ones with more rigorous and selective criteria for acceptability. This is reflected in their track records for quality, including correlates of quality and impact such as citations, downloads and the many rich new metrics that the online and OA era will be generating.

JE: “What will the cost of marketing to attract the best authors be?”

It is not "marketing" but the journal's track record for quality standards and impact that attract authors and content in peer-reviewed research publication. Marketing is for subscribers (institutional and individual); for authors and their institutions it is standards and metrics that matter.

And, before someone raises the question: Yes, metrics can be manipulated and abused, in the short term, but cheating can also be detected, especially as deviations within a rich context of multiple metrics. Manipulating a single metric (e.g., robotically inflating download counts) is easy, but manipulating a battery of systematically intercorrelated metrics is not; and abusers can and will be named and shamed. In research and academia, this risk to track record and career is likely to counterbalance the temptation to cheat. (Let's not forget that metrics, like the content they are derived from, will be OA too...)

JE: “I am not myself aware of any financial modeling that attempts to grapple with an environment where there are not a handful of such services but 200, 400, more.”

There are already at least 25,000 such services (journals) now! There will be about the same number post-Green-OA.

The only thing that would change (on the hypothesis that universal Green OA will eventually make subscriptions unsustainable) is that the 25,000 post-Green-OA journals would only provide peer review: no more print edition, online edition, distribution, archiving, or marketing (other than each journal's quality track record itself, and its metrics). Gone too would be the costs of these obsolete products and services, and their marketing.

(Probably gone too will be the big-bucks era of journal-fleet publishing. Unlike with books, it has always been the individual journal's name and track record that has mattered to authors and their institutions and funders, not their fleet-publisher's imprimatur. Software for implementing peer review online will provide the requisite economy of scale at the individual journal level: no need to co-bundle a fleet of independent journals and fields under the same operational blanket.)

JE: “As these services develop and authors seek the best one, what new investments will be necessary in such areas as information technology?”

The best peer review is provided by the best peers (for free), applying the highest quality standards. OA metrics will grow and develop (independent of publishers), but peer review software is pretty trivial and probably already quite well developed (hence hopes of

"patenting" new peer review "systems" are probably pipe-dreams.)

JE: “Will the fixed costs of managing such a service rise along with greater demands by the most significant authors?”

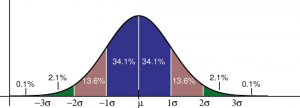

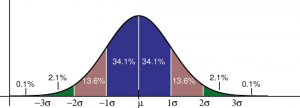

The journal quality hierarchy will remain pretty much as it is now, with the highest-quality (hence most selective) journals the fewest, at the top, grading down to the many average-level journals, and then the near-vanity press at the bottom (since just about everything eventually gets published somewhere, especially in the online era).

(I also think that "

no-fault peer review" will evolve as a natural matter of course -- i.e., authors will pay a standard fee per round of peer review,

independent of outcome: acceptance, revision/re-refereeing or rejection. So being rejected by a higher-level journal will not be a dead loss, if the author is ready to revise for a lower-level journal in response to the higher-level journal's review. Nor will rejected papers be an unfair burden, bundled into the fee of the authors of accepted papers.)

JE: “As more services proliferate, what will the cost of submitting material on an author-pays basis be?”

There will be no more new publishing services, apart from peer review (and possibly some copy-editing), and no more new journals either; 25,000 is probably enough already! And the cost per round of refereeing should not prove more than about $200.

JE: “Will the need to attract the best authors drive prices down?”

There will be no "need to attract the best authors," but the best journals will get them by maintaining the highest standards.

Since the peers review for free, the cost per round of refereeing is small and pretty fixed.

JE: “If prices are driven down, is there any way for such a service to operate profitably as the costs of marketing and technology grow without attempting to increase in volume what is lost in margin?”

Peer-reviewed journal publishing will no longer be big business; just a modest scholarly service, covering its costs.

JE: “If such services must increase their volume, will there be inexorable pressure to lower some of the review standards in order to solicit more papers?”

There will be no pressure to increase volume (why should there be)? Scholars try to meet the highest quality standards they can meet. Journals will try to maintain the highest quality standards they can maintain.

JE: “What is the proper balance between the right fee for authors, the level of editorial scrutiny, and the overall scope of the service, as measured by the number of articles developed?”

Much ado about little, here.

The one thing to remember is that there is a trade-off between quality-standards and volume: The more selective a journal, the smaller is the percentage of all articles in a field that will meet its quality standards. The "price" of higher selectivity is lower volume, but that is also the prize of peer-reviewed publishing: Journals aspire to high quality and authors aspire to be published in journals of high quality.

No-fault refereeing fees will help distribute the refereeing load (and cost) better than (as now) inflating the fees of accepted papers to cover the costs of rejected papers (rather like a shop-lifting surcharge!). Journals lower in the quality hierarchy will (as always) be more numerous, and will accept more papers, but authors are likely to continue to try a top-down strategy (as now), trying their luck with a higher-quality journal first.

There will no doubt be unrealistic submissions that can (as now) be summarily rejected without formal refereeing (or fee). The authors of papers that do merit full refereeing may elect to pay for refereeing by a higher-level journal, at the risk of rejection, but they can then use their referee reports to submit a more roadworthy version to a lower-level journal. With no-fault refereeing fees, both journals are paid for their costs, regardless of how many articles they actually accept for publication. (PotGutenberg publication means, I hasten to add, that accepted papers are certified with the name and track-record of the accepting journal, but those names just serve as the metadata for the Green OA version self-archived in the author's institutional repository.)

Harnad, S. (2009) The PostGutenberg Open Access Journal. In: Cope, B. & Phillips, A (Eds.) The Future of the Academic Journal. Chandos.

Harnad, S (2010) No-Fault Refereeing Fees: The Price of Selectivity Need Not Be Access Denied or Delayed. (Draft under refereeing).

And let's not forget what peer-reviewed research publishing is about, and for: It is not about provisioning a publishing industry but about providing a service to research, researchers, their institutions and their funders. Gutenberg-era publication costs meant that the Gutenberg publisher evolved, through no fault of its own, into the tail that wagged the paper-trained research pooch; in the PostGutenberg era, things will at last rescale into more proper and productive anatomic proportions...

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Whether on the non-OA subscription model or on the Gold-OA author-pays model, the only way scholarly/scientific journals compete for content is through their peer-review standards: The higher-quality journals are the ones with more rigorous and selective criteria for acceptability. This is reflected in their track records for quality, including correlates of quality and impact such as citations, downloads and the many rich new metrics that the online and OA era will be generating.

Whether on the non-OA subscription model or on the Gold-OA author-pays model, the only way scholarly/scientific journals compete for content is through their peer-review standards: The higher-quality journals are the ones with more rigorous and selective criteria for acceptability. This is reflected in their track records for quality, including correlates of quality and impact such as citations, downloads and the many rich new metrics that the online and OA era will be generating.