Friday, August 19. 2011

Gaulé, Patrick & Maystre, Nicolas (2011) Getting cited: Does open access help? Research Policy (in press) G & M: "Cross-sectional studies typically find positive correlations between free availability of scientific articles (‘open access’) and citations… Using instrumental variables, we find no evidence for a causal effect of open access on citations. We provide theory and evidence suggesting that authors of higher quality papers are more likely to choose open access in hybrid journals which offer an open access option. Self-selection mechanisms may thus explain the discrepancy between the positive correlation found in Eysenbach (2006) and other cross-sectional studies and the absence of such correlation in the field experiment of Davis et al. (2008)… Our results may not apply to other forms of open access beyond journals that offer an open access option. Authors increasingly self-archive either on their website or through institutional repositories. Studying the effect of that type of open access is a potentially important topic for future research..."

What the Gaulé & Maystre (G&M) (2011) article shows -- convincingly, in my opinion -- is that in the case of paid hybrid gold OA, most of the observed citation increase is better explained by the fact that the authors of articles that are more likely to be cited are also more likely to pay for hybrid gold OA. (The effect is even stronger when one takes into account the phase in the annual funding cycle when there is more money available to spend.)

But whether or not to pay money for the OA is definitely not a consideration in the case of Green OA ( self-archiving), which costs the author nothing. (The exceedingly low infrastructure costs of hosting Green OA repositories per article are borne by the institution, not the author: like the incomparably higher journal subscription costs, likewise borne by the institution, they are invisible to the author.)

I rather doubt that G & M's economic model translates into the economics of doing a few extra author keystrokes -- on top of the vast number of keystrokes already invested in keying in the article itself and in submitting and revising it for publication.

It is likely, however -- and we have been noting this from the very outset -- that one of the multiple factors contributing to the OA citation advantage (alongside the article quality factor, the article accessibility factor, the early accessibility factor, the competitive [OA vs non-OA] factor and the download factor) is indeed an author self-selection factor that contributes to the OA citation advantage.

What G & M have shown, convincingly, is that in the special case of having to pay for OA in a hybrid Gold Journal ( PNAS: a high-quality journal that makes all articles OA on its website 6 months after publication), the article quality and author self-selection factors alone (plus the availability of funds in the annual funding cycle) account for virtually all the significant variance in the OA citation advantage: Paying extra to provide hybrid Gold OA during those first 6 months does not buy authors significantly more citations.

G & M correctly acknowledge, however, that neither their data nor their economic model apply to Green OA self-archiving, which costs the author nothing and can be provided for any article, in any journal (most of which are not made OA on the publisher's website 6 months after publication, as in the case of PNAS). Yet it is on Green OA self-archiving that most of the studies of the OA citation advantage (and the ones with the largest and most cross-disciplinary samples) are based.

I also think that because both citation counts and the OA citation advantage are correlated with article quality there is a potential artifact in using estimates of article or author quality as indicators of author self-selection effects: Higher quality articles are cited more, and the size of their OA advantage is also greater. Hence what would need to be done in a test of the self-selection advantage for Green OA would be to estimate article/author quality [but not from their citation counts, of course!] for a large sample and then -- comparing like with like -- to show that among articles/authors estimated to be at the same quality level, there is no significant difference in citation counts between individual articles (published in the same journal and year) that are and are not self-archived by their authors.

No one has done such a study yet -- though we have weakly approximated it ( Gargouri et al 2010) using journal impact-factor quartiles. In our approximation, there remains a significant OA advantage even when comparing OA (self-archived) and non-OA articles (same journal/year) within the same quality-quartile. There is still room for a self-selection effect between and within journals within a quartile, however (a journal's impact factor is an average across its individual articles; PNAS, for example, is in the top quartile, but its individual articles still vary in their citation counts). So a more rigorous study would have to tighten up the quality equation much more closely). But my bet is that a significant OA advantage will be observed even when comparing like with like.

Stevan Harnad

EnablingOpenScholarship

Monday, August 15. 2011

Across the eight years since its launch in 2003, SHERPA Romeo's importance and value as a resource have been steadily increasing. The most recently announced upgrade covers 18,000 journals and is (1) More up to Date, with (2) More Accurate Journal Level Searching, (3) More Search Options, (4) Electronic ISSNs, and (5) Faster Performance.

In addition to congratulating SHERPA Romeo, let me use this occasion to repeat the plea I made eight years ago to adjust the colour code to provide the information that users need the most (and at the same time bring the colour coding in line with the terminology that has since gained wide currency: "Green OA"):

Although the distinction between journals that endorse the immediate OA self-archiving of both the refereed postprint and the pre-refereeing preprint ( P+p) and journals that endorse the immediate OA self-archiving of the refereed postprint but not the pre-refereeing preprint ( P) is not completely empty, it is of incomparably less importance and relevance to OA than the distinction between journals that do and do not endorse the immediate OA self-archiving of the refereed postprint ( P vs. not-P).

It is OA self-archiving of the refereed postprint that the OA movement is about and for. And it is OA self-archiving of the refereed postprint that is meant by the term "Green OA."

And yet SHERPA Romeo continues to code P+p as "green" and P as "blue"!

There is no "Blue OA." And the over 200 funders and institutions that have already mandated Green OA have not mandated "Blue OA": They could not care less whether the journals endorse the self-archiving of the unrefereed preprint in addition to the refereed postprint: Green OA only concerns the refereed postprint.

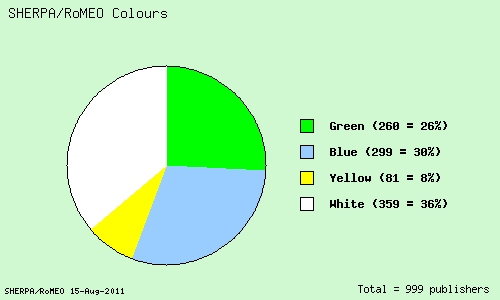

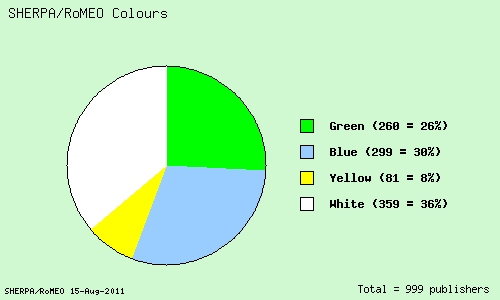

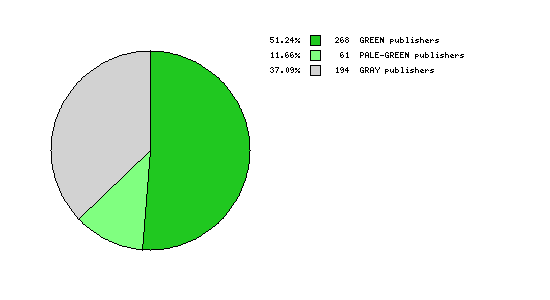

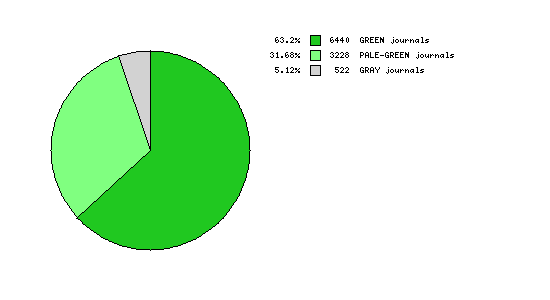

It is for this reason that EPrints Romeo has steadfastly generated a colour-corrected version of the SHERPA Romeo summary statistics pie-chart across these eight years -- in addition to generating the statistics for journals as well as for publishers. (SHERPA Romeo originally covered only publishers, but the statistics for journals are much more informative -- and positive -- than the statistics for publishers, since one publisher might publish one journal and another might publish 2000!.)

To see the immediate gain in clarity and consistency from suppressing the P+p/ P ("green"/"blue") distinction in the summary statistics, compare the SHERPA Romeo and EPrints Romeo summary pies for publishers below. (Note that the EPrints Romeo data are static, because they have not been updated for several years. The eye will show that for publishers the proportions are much the same, but have gotten somewhat better in recent years.)

I beg SHERPA Romeo to add the simplified, colour-corrected pie alongside its particoloured one (with the explanation that in the OA world, "Green" means P, not just P+p.). It would make a world of difference for user understanding.

In addition, now that SHERPA is covering the data at the individual journal level, I urge providing the journal-level pie too, for it not only gives a more realistic picture, but an even more positive one.

SHERPA Romeo's current "Green = Green" & "Blue = Green" publisher pie-chart (based on proportions of publishers):

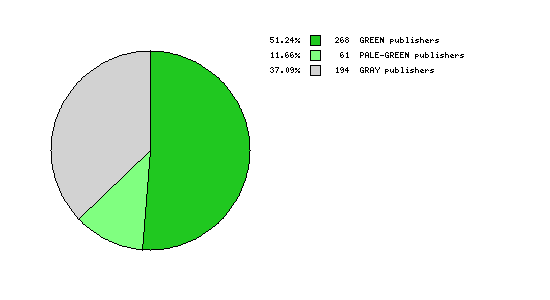

EPrints Romeo's colour-corrected publisher pie-chart, in which Green = Green OA (and preprints-only endorsements are coded as "pale green") (based on proportions of publishers, but out of date by several years):

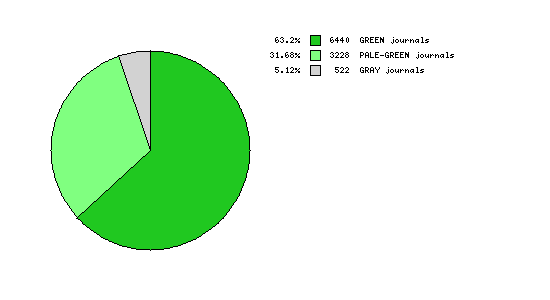

EPrints Romeo's colour-corrected journals pie-chart, in which Green = Green OA (and preprints-only endorsements are coded as "pale green") (based on proportions of journals). Note that the overall proportions are even better (but these data are out of date by several years, hence need updating, though they will not change much, as they already covered most of the big publishers, with the largest number of journals):

Stevan Harnad

EnablingOpenScholarship

Saturday, August 13. 2011

Comments on: Ginsparg, Paul (2011) Arxiv at 20. Nature 476: 145–147 doi:10.1038/476145a

&

Fischman, Josh (2011) Anonymous FTP Achives. The First Free Research-Sharing Site, arXiv, Turns 20 With an Uncertain Future. Chronicle of Higher Education August 10, 2011 Anonymous FTP archives. Arxiv (1991) was an invaluable milestone on the road to Open Access. But it was not the first free research-sharing site: That began in the 1970's with the internet itself, with authors making their papers freely accessible to all users net-wide by self-archiving them in their own local institutional " anonymous FTP archives."

Distributed local websites. With the creation of the world wide web in 1990, HTTP began replacing FTP sites for the self-archiving of papers on authors' institutional websites. FTP and HTTP sites were mostly local and distributed, but accessible free for all, webwide. Arxiv was the first important central HTTP site for research self-archiving, with physicists webwide all depositing their papers in one central locus (first hosted at Los Alamos). Arxiv's remarkable growth and success were due to both its timeliness and the fact that it had emerged from a widespread practice among high energy physicists that had already predated the web, namely, to share hard copies of their papers before publication by mailing them to central preprint distribution sites such as SLAC and CERN.

Central harvesting and search. At the same time, while physicists were taking to central self-archiving, in other disciplines (particularly computer science), distributed self-archiving continued to grow. Later web developments, notably google and webwide harvesting and search engines, continued to make distributed self-archiving more and more powerful and attractive. Meanwhile, under the stimulus of Arxiv itself, the Open Archives Initiative (OAI) was created in 1999 -- a metadata-harvesting protocol that made all distributed OAI-compliant websites interoperable, as if their distributed local contents were all in one global, searchable archive.

No need for direct central deposit in google! Together, google and OAI probably marked the end of the need for central archives. The cost and effort can instead be distributed across institutions, with all the essential search and retrieval functionality provided by automated central "overlay" services for harvesting, indexing, search and retrieval (e.g., OAIster, Scirus, Base and Google Scholar). Arxiv continues to flourish, because two decades of invaluable service to the physics community has several generations of users deeply committed to it. But no other dedicated central archive has arisen since. Like computer scientists, whose local, distributed self-archiving is harvested centrally by Citeseerx, economists, for example, self-archive institutionally, with central harvesting by RepEc.

Mandating self-archiving. In biomedicine, PubMed Central looks to be an exception, with direct central depositing rather than local. But PubMed Central was not a direct author initiative, like anonymous FTP, author websites or Arxiv. It was designed by NLM, deposit was mandated by NIH, and deposit is done not only by authors but by publishers.

Institutions are the universal research providers. Open Access is still growing far more slowly than it might, and one of the factors holding it back might be notional conflicts between institutional and central archiving. It is clear that Open Access self-archiving will have to be universally mandated, if all disciplines are to enjoy its benefits (maximized research access, uptake, usage and impact, minimized costs). The universal providers of all research paper output, funded and unfunded, are the world's universities and research institutions, distributed globally across all scholarly and scientific disciplines, all languages, and all national boundaries.

Deposit institutionally, harvest centrally. Hence funder self-archiving mandates like NIH's and institutional self-archiving mandates like Harvard's need to join forces to reinforce one another rather than to complete for the same papers, and the most natural, efficient and economical way to do this is for both institutiions and funders to mandate that all self-archivingshould be done locally, in the author's institutional OAI-compliant repository. The contents of the institutional repositories can then be harvested automatically by central OAI-compliant repositories such as PubMed Central (as well as by google and other central harvesters) for global indexing and search.

Distribute the archiving, rather than the cost. In this light, Arxiv's self-funding pains may be a wake-up call: Why should Cornell University (or a "wealthy donor") subsidize a cost that institutions can best "sponsor" by each doing (and mandating) their own distributed archiving locally (thereby reducing total cost, to boot)? After all, no one deposits directly in Google…

Stevan Harnad

EnablingOpenScholarship

"How to Integrate University and Funder Open Access Mandates"

SUMMARY: Research funder open-access mandates (such as NIH's) and university open-access mandates (such as Harvard's) are complementary. There is a simple way to integrate them to make them synergistic and mutually reinforcing:

Universities' own Institutional Repositories (IRs) are the natural locus for the direct deposit of their own research output: Universities (and research institutions) are the universal research providers of all research (funded and unfunded, in all fields) and have a direct interest in archiving, monitoring, measuring, evaluating, and showcasing their own research assets -- as well as in maximizing their uptake, usage and impact.

Both universities and funders should accordingly mandate deposit of all peer-reviewed final drafts (postprints), in each author's own university IR, immediately upon acceptance for publication, for institutional and funder record-keeping purposes. Access to that immediate postprint deposit in the author's university IR may be set immediately as Open Access if copyright conditions allow; otherwise access can be set as Closed Access, pending copyright negotiations or embargoes. All the rest of the conditions described by universities and funders should accordingly apply only to the timing and copyright conditions for setting open access to those deposits, not to the depositing itself, its locus or its timing.

As a result, (1) there will be a common deposit locus for all research output worldwide; (2) university mandates will reinforce and monitor compliance with funder mandates; (3) funder mandates will reinforce university mandates; (4) legal details concerning open-access provision, copyright and embargoes will be applied independently of deposit itself, on a case by case basis, according to the conditions of each mandate; (5) opt-outs will apply only to copyright negotiations, not to deposit itself, nor its timing; and (6) any central OA repositories can then harvest the postprints from the authors' IRs under the agreed conditions at the agreed time, if they wish.

Thursday, August 11. 2011

Re: Re: " Research intelligence - 'We all aspire to universal access'" Times Higher Education 11 August 2011

The publishing community can afford to be leisurely about how long it takes for open access (OA) to reach 100% (it's 10% now for Gold OA publishing, plus another 20% for Green OA self-archiving). But the research community need not be so leisurely about it. Research articles no longer need to be accessible only to those researchers whose institution can afford to subscribe to the journal in which it was published, rather than to all researchers who want to use, apply and build upon it. Lost research access means lost research progress. Research is funded, conducted and published for the sake of research progress and its public benefits, not in order to provide revenue to the publishing industry, nor to sustain the subscription model of cost-recovery.

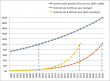

The publishing community is understandably "wary" about Green OA self-archiving, mindful of its subscription revenue streams. But the transition to Green OA self-archiving, unlike the transition to Gold OA publishing, is entirely in the hands of the research community, which need not wait passively for the "market" to shift to Gold OA publishing: Springer publishers' projections suggest that at its current growth rate Gold OA will not reach 100% till the year 2029.

The research community need not wait, because it is itself the universal provider of all the published research, and its institutions and funders can mandate (i.e., require) that their authors self-archive their peer-reviewed final drafts (not the publishers' version of record) in their institutional Green OA repositories immediately upon acceptance for publication. And a growing number of funders and institutions (including all the UK funding councils, the ERC, EU and NIH in the US, as well as University College London, Harvard and MIT) are doing just that.

Green OA self-archiving mandates generate 60% OA within two years of adoption, and climb toward 100% within a few years thereafter. The earliest mandates (U. Southampton School of Electrons and Computer Science, 2003, and CERN, 2004 are already at or near 100% Green OA.

Stevan Harnad

EnablingOpenScholarshipHarnad, S. (2011) Gold Open Access Publishing Must Not Be Allowed to Retard the Progress of Green Open Access Self-Archiving. Logos 21(3-4): 86-93 /

ABSTRACT: Universal Open Access (OA) is fully within the reach of the global research community: Research institutions and funders need merely mandate (green) OA self-archiving of the final, refereed drafts of all journal articles immediately upon acceptance for publication. The money to pay for gold OA publishing will only become available if universal green OA eventually makes subscriptions unsustainable. Paying for gold OA pre-emptively today, without first having mandated green OA not only squanders scarce money, but it delays the attainment of universal OA.

Harnad, S. (2011) Open Access to Research: Changing Researcher Behavior Through University and Funder Mandates. JEDEM Journal of Democracy and Open Government 3 (1): 33-41.

ABSTRACT: The primary target of the worldwide Open Access initiative is the 2.5 million articles published every year in the planet's 25,000 peer-reviewed research journals across all scholarly and scientific fields. Without exception, every one of these articles is an author give-away, written, not for royalty income, but solely to be used, applied and built upon by other researchers. The optimal and inevitable solution for this give-away research is that it should be made freely accessible to all its would-be users online and not only to those whose institutions can afford subscription access to the journal in which it happens to be published. Yet this optimal and inevitable solution, already fully within the reach of the global research community for at least two decades now, has been taking a remarkably long time to be grasped. The problem is not particularly an instance of "eDemocracy" one way or the other; it is an instance of inaction because of widespread misconceptions (reminiscent of Zeno's Paradox). The solution is for the world's research institutions and funders to (1) extend their existing "publish or perish" mandates so as to (2) require their employees and fundees to maximize the usage and impact of the research they are employed and funded to conduct and publish by (3) depositing their final drafts in their Open Access (OA) Institutional Repositories immediately upon acceptance for publication in order to (4) make their findings freely accessible to all their potential users webwide. OA metrics can then be used to measure and reward research progress and impact; and multiple layers of links, tags, commentary and discussion can be built upon and integrated with the primary research.

Harnad, S. (2010) The Immediate Practical Implication of the Houghton Report: Provide Green Open Access Now. Prometheus 28 (1): 55-59.

ABSTRACT: Among the many important implications of Houghton et al’s (2009) timely and illuminating JISC analysis of the costs and benefits of providing free online access (“Open Access,” OA) to peer-reviewed scholarly and scientific journal articles one stands out as particularly compelling: It would yield a forty-fold benefit/cost ratio if the world’s peer-reviewed research were all self-archived by its authors so as to make it OA. There are many assumptions and estimates underlying Houghton et al’s modelling and analyses, but they are for the most part very reasonable and even conservative. This makes their strongest practical implication particularly striking: The 40-fold benefit/cost ratio of providing Green OA is an order of magnitude greater than all the other potential combinations of alternatives to the status quo analyzed and compared by Houghton et al. This outcome is all the more significant in light of the fact that self-archiving already rests entirely in the hands of the research community (researchers, their institutions and their funders), whereas OA publishing depends on the publishing community. Perhaps most remarkable is the fact that this outcome emerged from studies that approached the problem primarily from the standpoint of the economics of publication rather than the economics of research.

|

Re: "

Re: "