Wednesday, February 4. 2009

This is the timely and incisive analysis of what is at stake in the question of locus of deposit (institutional vs. central) for open access self-archiving mandates. It was written (in French, and then translated into English) by Prof. Bernard Rentier, Rector of the University of Liège and founder of EurOpenScholar. It is re-posted here from Prof. Rentier's blog.

This is the timely and incisive analysis of what is at stake in the question of locus of deposit (institutional vs. central) for open access self-archiving mandates. It was written (in French, and then translated into English) by Prof. Bernard Rentier, Rector of the University of Liège and founder of EurOpenScholar. It is re-posted here from Prof. Rentier's blog.

For more background on the important current issues underlying the question of institutional vs. central deposit mandates by universities and research funders, click here.

Liège is one of the c. 30 institutions (plus 30 funders) worldwide that have already adopted a Green OA self-archiving mandate .

Repositories: Institutional, Thematic, or Central?Posted by Bernard Rentier in Open Access

[Also recommended: a remarkable and very complete review of OA by Peter Suber.]

The “Green Open Access (OA)” solution, providing free access to research publications in Institutional Repositories (IRs) via the Web, is certainly the best one, but sooner or later it will face a new wave of centralised thematic or funder repositories (CRs).

The latest initiative comes from the very active EUROHORCs (European Association of Heads of Research Funding Organisations and Research Performing Organisations), well known for its EURYI prizes and its prominent influence on European thinking in the research area. EUROHORCs is working to convince the European Science Foundation (ESF) to set up, through a large subsidy from the EC, a centralised repository (CR) which would be both thematic (Biomedical) and geographic (European). The concept is inspired by PubMed Central, among others.

The EUROHORCs initiative is very well-intentioned. It is based on an awareness that many of us share: It is of the utmost importance that science funded by public money should be made freely and easily accessible to the public (OA). But the initiative also reveals a profound misunderstanding about what OA and researchers’ real needs are all about.

The vision underlying the EUROHORCs initiative is that research results should be deposited directly in a CR. However, if research results are not OA today, this is not because of the lack of a CR to deposit them in, but rather because most authors are simply not yet depositing their articles at all, not even in an IR.

Creating a new repository is hence not the solution for making research OA. The solution lies in universal deposit mandates, from both institutions and funding agencies. If this task is left to large funders such as the European Community, their central repositories will only contain publications of the research they have funded. From this it is easy to see that researchers will ultimately have to deposit their publications in as many repositories as there are funders supporting their research. Not only is this not practical, it is needlessly cumbersome.

The obvious solution is that both research institutions and funding agencies should jointly require IR deposit. Once that systematic coordination has been successfully implemented, if CRs are desired, they can easily be created and filled using compatible software for exporting or harvesting automatically from IRs to CRs.

What is worrisome is the needless double investment in creating two distinct kinds of repositories for direct deposit. This trend seems to rest on the naive notion that, in the Internet era, it is somehow still necessary to deposit things centrally. But in reality, the centralising tool is the harvester, and its search engine. Google Scholar, for example, is quite efficient in finding articles in any repository, institutional or central, yet no one deposits articles directly in Google Scholar. The perceived need for direct-deposit CRs is groundless, technically speaking. Such CRs even run the risk of serving as hosts for only the publications funded by a single funder. IRs guarantee OA webwide for all research output, in all disciplines, from all institutions, regardless of where (or whether) it has been funded.

It is understandable that funders may wish to host a complete collection of the research they have funded, but nowadays that can easily be accomplished by importing it automatically from the more complete collections of the distributed IRs -- since institutions are the universal providers of all research output, funded and unfunded -- as long as funders collaborate with institutions in first ensuring that all the IRs are filled with their own institutional research output.

Besides, the OA philosophy is global. It cannot be reduced to a single continent. Science is universal.

Giving priority to creating more CRs for direct deposit today is not only a waste of time: it is also counterproductive for the growth of convergent funder and institutional mandates. It would generate multiple competing loci of primary deposit for authors -- most of whom, we must not forget, are still not depositing at all.

In conclusion, it seems far more efficient to focus first on filling IRs at this time; once that is accomplished, if it is judged useful, CRs can be configured to collect their data from IRs rather than being used as divergent points of direct deposit themselves.

The potential success of OA, without conflicting head-on with publishers, rests on the deposit of authors' own final drafts of their published articles, through a one-time, simple action on the part of the author. All research is generated from research institutions: IRs are hence the natural locus for author deposit, providing optimal proximity, convenience and congruence with the mission of the author's own institution. The rest is merely technical: a matter of automated data transfer to external CRs.

The EUROHORCs proposal is only worthwhile if it contributes to the secondary harvesting of data from primary IRs. Otherwise, it is missing the point of OA.

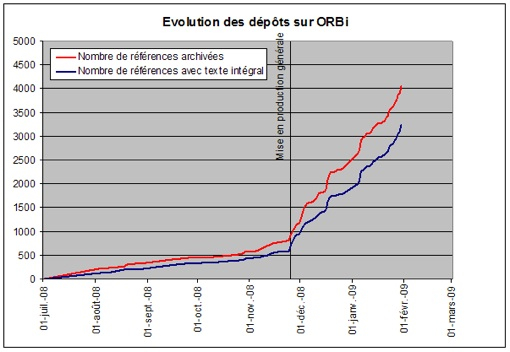

ORBi wins its challenge

U. Liège's IR "ORBi" (Open Repository and Bibliography) is fulfilling its promise: over 4,000 references have already been filed since November 26th and, in a happy surprise, 79% of these articles turn out to be full text. This is thus ahead of schedule for our institutional Green OA Mandate (announced in March 2007 to take effect in October 2009): "Whenever the university reviews faculty publications for promotion, tenure, funding, or any other internal purpose, the review will be based exclusively on full texts deposited in the IR."

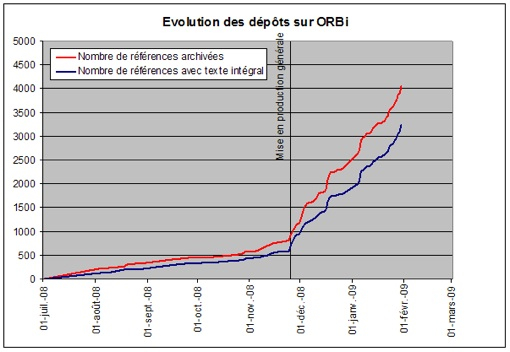

The graph below shows clearly how the IR contents are growing. And yet a quick calculation also reminds us that we are still far from capturing the actual number of papers published yearly by our university authors.

[Funder mandates can help accelerate and motivate both the adoption of institutional mandates like ours, and author compliance with them -- provided the funder mandates stipulate the author's IR as the single convergent locus for direct deposit (followed by automatized harvest to CRs). If funders instead insist upon direct central deposit in their external CRs, they simply create a needless retardant and disincentive for author compliance, and hence for universal OA, rather than reinforcing and facilitating them.]

Posté par Bernard Rentier dans Open Access

A lire: une remarquable revue très complète de l’OA par Peter Suber.

La formule des dépôts institutionnels permettant la libre consultation de publications de recherche par l’Internet est certes la meilleure, mais elle est, tôt ou tard, menacée par une nouvelle tendance visant à créer des dépôts thématiques ou des dépôts gérés par des organismes finançant la recherche.

La dernière initiative provient de la très active association EUROHORCs (European association of the heads of research funding organisations and research performing organisations), bien connue pour ses prix EURYI et dont l’influence sur la réflexion européenne en matière de recherche est considérable. Elle tente de convaincre l’European Science Foundation (ESF) de mettre sur pied, grâce à une subvention considérable des Communautés européennes, un dépôt centralisé qui serait à la fois thématique (sciences biomédicales) et localisé (Europe) sur base du principe qui a conduit à la création de PubMed Central, par exemple.

L’idée part d’un bon sentiment. Elle est née d’une prise de conscience que nous partageons tous: il est impératif que la science financée par les deniers publics soit rendue publique gratuitement et commodément. Mais en même temps, elle est fondée sur une profonde méconnaissance de l’Open Access, de l’Open Access Initiative et des besoins réels des chercheurs et des pouvoirs subsidiants.

La notion qui sous-tend cette initiative est que les résultats de la recherche doivent être déposés directement dans un dépôt centralisé. Mais si les résultats de la recherche ne sont pas aujourd’hui en accès libre et ouvert, ce n’est pas parce qu’il manque des dépôts centralisés, c’est tout simplement parce que la plupart des auteurs ne déposent pas leurs articles du tout, même pas dans un dépôt institutionnel.

La solution n’est donc pas de créer un nouveau dépôt. Elle est dans l’obligation pour les chercheurs de déposer leur travail dans un dépôt électronique, cette obligation devant être exigée par les universités et institutions de recherche ainsi que par les organismes finançant la recherche. Si l’on se contente de laisser faire les grands pourvoyeurs de fonds tels que l’Union européenne, on ne disposera dans le dépôt central que des publications de la recherche qu’ils ont financée. On comprend donc qu’àterme, le chercheur sera amené à encoder ses publications dans autant de dépôts différents qu’il bénéficiera de fonds d’origine différente. Ce n’est pas pratique, c’est même inutilement lourd.

Comme les institutions de recherche la produisent (avec ou sans financement public, dans toutes les disciplines, dans tous les pays, dans toutes les langues), la solution qui saute aux yeux est qu’ensemble, les institutions de recherche et les organismes finançants doivent encourager la mise en place de dépôts institutionnels. Ensuite, si l’on tient à réaliser des dépôts centralisés, on pourra toujours le faire, en redondance, et ce sera facile si les logiciels sont compatibles.

Ce qui est inquiétant, c’est l’investissement, redondant à ce stade, qu’implique la création de dépôts centralisés. En fait, ceci correspond à une vision naïve qui laisse penser qu’à l’heure de l’Internet, il faille encore centraliser quoi que ce soit. L’élément centralisateur, c’est le moteur de recherche. Prenons Google Scholar: il est parfaitement efficace pour retrouver les articles dans l’ensemble des dépôts institutionnels, aussi bien que dans un dépôt central. L’utilité des dépôts centralisés n’est donc pas justifiable sur le plan technique. Le risque est même qu’ils ne solidifient uniquement que le dépôt des travaux faits avec les fonds d’un seul bailleur de fonds. Les dépôts institutionnels assurent la présence sur le web de tous les travaux scientifiques quels qu’ils soient, peu importe comment ils sont financés.

On peut comprendre que les bailleurs de fonds et organismes finançants aient envie de disposer d’un répertoire complet des travaux qu’ils subsidient, mais il est logique alors qu’ils collectent les données — c’est maintenant très aisé techniquement et cela nécessite juste un peu d’organisation pour être systématique — à partir des dépôts institutionnels plus complets ou que ces derniers leur communiquent automatiquement l’information.

Par ailleurs, la philosophie qui sous-tend l’Open Access est planétaire. Elle ne peut se confiner à une dimension européenne. La science est plus universelle que cela.

La création de dépôts centralisés n’est pas seulement une perte de temps, elle est aussi contre-productive pour la généralisation du dépôt obligatoire car elle multiplie, pour des chercheurs qui résistent déjà à déposer ne fût-ce qu’une fois leurs travaux, elle multiplie les endroits où ils doivent les déposer !

Nous sommes donc en présence d’une initiative de très bonne volonté, qui a du sens pour l’ESF, mais qui est un peu maladroite. Il eût été préférable de développer le principe que les dépôts centralisés soient des récoltants d’informations à partir des dépôts institutionnels et non des endroits de dépôt direct. Le principe même des dépôts thématiques (par sujet, par domaine de la science, par nationalité, par continent, par source de financement, etc.) ne peut qu’ajouter à la confusion dans un domaine qui n’est déjà pas facile à mettre en place et où le succès le plus complet est lié à la proximité du niveau de pouvoir et d’exigence. Les dépôts thématiques (ici, il serait doublement sectoriel: Europe & Biomédecine) ont beaucoup de sens, mais doivent rester secondaires par rapport à l’exigence fondamentale du “tout accessible”.

En d’autres termes, le succès de l’Open Access, sans se heurter de front aux éditeurs, repose sur les dépôts d’articles publiés par ailleurs et sur l’exigence d’un travail unique pour l’auteur. Le plus simple et le plus efficace pour cela est le dépôt institutionnel. Toute recherche provient d’institutions: le dépôt idéal le plus efficace et le plus complet ne peut donc être qu’institutionnel. Le reste est technique: ce n’est plus qu’une affaire de récolte d’informations.

La proposition de l’ESF n’est donc intéressante que si elle se situe au niveau de la récolte secondaire des données à partir des dépôts institutionnels primaires. Dans sa présentation actuelle, elle manque son but.

|