Quicksearch

Your search for Davis returned 26 results:

Monday, February 8. 2010

Open Access: Self-Selected, Mandated & Random; Answers & Questions

Gargouri, Y., Hajjem, C., Lariviere, V., Gingras, Y., Brody, T., Carr, L. and Harnad, S. (2010) Self-Selected or Mandated, Open Access Increases Citation Impact for Higher Quality Research.(Submitted)We are happy to have performed these further analyses, and we are very much in favor of this sort of open discussion and feedback on pre-refereeing preprints of papers that have been submitted and are undergoing peer review. They can only improve the quality of the eventual published version of articles.

However, having carefully responded to Phil's welcome questions, below, we will, at the end of this posting, ask Phil to respond in kind to a question that we have repeatedly raised about his own paper (Davis et al 2008), published a year and a half ago...

RESPONSES TO DAVIS'S QUESTIONS ABOUT OUR PAPER:

PD:We are very appreciative of your concern and hope you will agree that we have not been interested only in what the referees might have to say. (We also hope you will now in turn be equally responsive to a longstanding question we have raised about your own paper on this same topic.)

"Stevan, Granted, you may be more interested in what the referees of the paper have to say than my comments; I'm interested in whether this paper is good science, whether the methodology is sound and whether you interpret your results properly."

PD:Our article supports its conclusions with several different, convergent analyses. The logistical analysis with the odds ratio is one of them, and its results are fully corroborated by the other, simpler analyses we also reported, as well as the supplementary analyses we append here now.

"For instance, it is not clear whether your Odds Ratios are interpreted correctly. Based on Figure 4, OA article are MORE LIKELY to receive zero citations than 1-5 citations (or conversely, LESS LIKELY to receive 1-5 citations than zero citations). You write: "For example, we can say for the first model that for a one unit increase in OA, the odds of receiving 1-5 citations (versus zero citations) increased by a factor of 0.957 [re: Figure 4 (p.9)]"... I find your odds ratio methodology unnecessarily complex and unintuitive..."

[Yassine has since added that your confusion was our fault because by way of an illustration we had used the first model (0 citations vs. 1-5 citations), with its odds ratio of 0.957 ("For example, we can say for the first model that for a one unit increase in OA, the odds of receiving 1-5 citations (versus zero citations) increased by a factor of 0.957 "). In the first model the value 0.957 is below and too close to 1 to serve as a good illustration of the meaning of the odds ratio. We should have chosen a better example. one in which (Exp(ß) is clearly greater than 1. We should have said: "For example, we can say for the second model that for a one unit increase in OA, the odds of receiving 5-10 citations (versus 1-5 citations) increased by a factor of 1.323." This clearer example will be used in the revised text of the paper. (See Figure 4S with a translation to display the deviations relative to an odds ratio of one rather than zero {although Excel here insists on labelling the baseline "0" instead of "1"! This too will be fixed in the revised text}.]

PD:Here is the analysis underlying Figure 4, re-done without CERN, and then again re-done without either CERN or Southampton. As will be seen, the outcome pattern, as well as its statistical significance, are the same whether or not we exclude these institutions. (Moreover, I remind you that those are multiple regression analyses in which the Beta values reflect the independent contributions of each of the variables: That means the significant OA advantage, whether or not we exclude CERN, is the contribution of OA independent of the contribution of each institution.)

"Similarly in Figure 4 (if I understand the axes correctly), CERN articles are more than twice as likely to be in the 20+ citation category than in the 1-5 citation category, a fact that may distort further interpretation of your data as it may be that institutional effects may explain your Mandated OA effect. See comments by Patrick Gaule and Ludo Waltman on the review"

PD:As noted in Yassine's reply to Phil, that formula was incorrectly stated in our text, once; in all the actual computations, results, figures and tables, however, the correct formula was used.

"Changing how you report your citation ratios, from the ratio of log citations to the log of citation ratios is a very substantial change to your paper and I am surprised that you point out this reporting error at this point."

PD:The log of the citation ratio was used only in displaying the means (Figure 2), presented for visual inspection. The paired-sample t-tests of significance (Table 2) were based on the raw citation counts, not on log ratios, hence had no leverage in our calculations or their interpretations. (The paired-sample t-tests were also based only on 2004-2006, because for 2002-2003 not all the institutional mandates were yet in effect.)

"While it normalizes the distribution of the ratios, it is not without problems, such as: 1. Small citation differences have very large leverage in your calculations. Example, A=2 and B=1, log (A/B)=0.3"

Moreover, both the paired-sample t-test results (2004-2006) and the pattern of means (2002-2006) converged with the results of the (more complicated) logistical regression analyses and subdivisions into citation ranges.

PD:As noted, the log ratios were only used in presenting the means, not in the significance testing, nor in the logistic regressions.

"2. Similarly, any ratio with zero in the denominator must be thrown out of your dataset. The paper does not inform the reader on how much data was ignored in your ratio analysis and we have no information on the potential bias this may have on your results."

However, we are happy to provide the additional information Phil requests, in order to help readers eyeball the means. Here are the means from Figure 2, recalculated by adding 1 to all citation counts. This restores all log ratios with zeroes in the numerator (sic); the probability of a zero in the denominator is vanishingly small, as it would require that all 10 same-issue control articles have no citations!

The pattern is again much the same. (And, as noted, the significance tests are based on the raw citation counts, which were not affected by the log transformations that exclude numerator citation counts of zero.)

This exercise suggested a further heuristic analysis that we had not thought of doing in the paper, even though the results had clearly suggested that the OA advantage is not evenly distributed across the full range of article quality and citeability: The higher quality, more citeable articles gain more of the citation advantage from OA.

In the following supplementary figure (S3), for exploratory and illustrative purposes only, we re-calculate the means in the paper's Figure 2 separately for OA articles in the citation range 0-4 and for OA articles in the citation range 5+.

The overall OA advantage is clearly concentrated on articles in the higher citation range. There is even what looks like an OA DISadvantage for articles in the lower citation range. This may be mostly an artifact (from restricting the OA articles to 0-4 citations and not restricting the non-OA articles), although it may also be partly due to the fact that when unciteable articles are made OA, only one direction of outcome is possible, in the comparison with citation means for non-OA articles in the same journal and year: OA/non-OA citation ratios will always be unflattering for zero-citation OA articles. (This can be statistically controlled for, if we go on to investigate the distribution of the OA effect across citation brackets directly.)

PD:We will be doing this in our next study, which extends the time base to 2002-2008. Meanwhile, a preview is possible from plotting the mean number of OA and non-OA articles for each citation count. Note that zero citations is the biggest category for both OA and non-OA articles, and that the proportion of articles at each citation level decreases faster for non-OA articles than for OA articles; this is another way of visualizing the OA advantage. At citation counts of 30 or more, the difference is quite striking, although of course there are few articles with so many citations:

"Have you attempted to analyze your citation data as continuous variables rather than ratios or categories?"

REQUEST FOR RESPONSE TO QUESTION ABOUT DAVIS ET AL'S (2008) PAPER:

Davis, PN, Lewenstein, BV, Simon, DH, Booth, JG, & Connolly, MJL (2008)Davis et al had taken a 1-year sample of biological journal articles and randomly made a subset of them OA, to control for author self-selection. (This is comparable to our mandated control for author self-selection.) They reported that after a year, they found no significant OA Advantage for the randomized OA for citations (although they did find an OA Advantage for downloads) and concluded that this showed that the OA citation Advantage is just an artifact of author self-selection, now eliminated by the randomization.

Open access publishing, article downloads, and citations: randomised controlled trial British Medical Journal 337

Critique of Davis et al's paper: "Davis et al's 1-year Study of Self-Selection Bias: No Self-Archiving Control, No OA Effect, No Conclusion" BMJ Responses.

What Davis et al failed to do, however, was to demonstrate that -- in the same sample and time-span -- author self-selection does generate the OA citation Advantage. Without showing that, all they have shown is that in their sample and time-span, they found no significant OA citation Advantage. This is no great surprise, because their sample was small and their time-span was short, whereas many of the other studies that have reported finding an OA Advantage were based on much larger samples and much longer time spans.

The question raised was about controlling for self-selected OA. If one tests for the OA Advantage, whether self-selected or randomized, there is a great deal of variability, across articles and disciplines, especially for the first year or so after publication. In order to have a statistically reliable measure of OA effects, the sample has to be big enough, both in number of articles and in the time allowed for any citation advantage to build up to become detectable and statistically reliable.

Davis et al need to do with their randomization methodology what we have done with our mandating methodology, namely, to demonstrate the presence of a self-selected OA Advantage in the same journals and years. Then they can compare that with randomized OA in those same journals and years, and if there is a significant OA Advantage for self-selected OA and no OA Advantage for randomized OA then they will have evidence that -- contrary to our findings -- some or all of the OA Advantage is indeed just a side-effect of self-selection. Otherwise, all they have shown is that with their journals, sample size and time-span, there is no detectable OA Advantage at all.

What Davis et al replied in their BMJ Authors' Response was instead this:

PD:This is not an adequate response. If a control condition was needed in order to make an outcome meaningful, it is not sufficient to reply that "the publisher and sample allowed us to do the experimental condition but not the control condition."

"Professor Harnad comments that we should have implemented a self-selection control in our study. Although this is an excellent idea, it was not possible for us to do so because, at the time of our randomization, the publisher did not permit author-sponsored open access publishing in our experimental journals. Nonetheless, self-archiving, the type of open access Prof. Harnad often refers to, is accounted for in our regression model (see Tables 2 and 3)... Table 2 Linear regression output reporting independent variable effects on PDF downloads for six months after publication Self-archived: 6% of variance p = .361 (i.e., not statistically significant)... Table 3 Negative binomial regression output reporting independent variable effects on citations to articles aged 9 to 12 months Self-archived: Incidence Rate 0.9 p = .716 (i.e., not statistically significant)..."

Nor is it an adequate response to reiterate that there was no significant self-selected self-archiving effect in the sample (as the regression analysis showed). That is in fact bad news for the hypothesis being tested.

Nor is it an adequate response to say, as Phil did in a later posting, that even after another half year or more had gone by, there was still no significant OA Advantage. (That is just the sound of one hand clapping again, this time louder.)

The only way to draw meaningful conclusions from Davis et al's methodology is to demonstrate the self-selected self-archiving citation advantage, for the same journals and time-span, and then to show that randomization wipes it out (or substantially reduces it).

Until then, our own results, which do demonstrate the self-selected self-archiving citation advantage for the same journals and time-span (and on a much bigger and more diverse sample and a much longer time scale), show that mandating the self-archiving does not wipe out the citation advantage (nor does it substantially reduce it).

Meanwhile, Davis et al's finding that although their randomized OA did not generate a citation increase, it did generate a download increase, suggests that with a larger sample and time-span there may well be scope for a citation advantage as well: Our own prior work and that of others has shown that higher early download counts tend to lead to higher citation counts later.

Bollen, J., Van de Sompel, H., Hagberg, A. and Chute, R. (2009) A principal component analysis of 39 scientific impact measures in PLoS ONE 4(6): e6022,

Brody, T., Harnad, S. and Carr, L. (2006) Earlier Web Usage Statistics as Predictors of Later Citation Impact. Journal of the American Association for Information Science and Technology (JASIST) 57(8) 1060-1072.

Lokker, C., McKibbon, K. A., McKinlay, R.J., Wilczynski, N. L. and Haynes, R. B. (2008) Prediction of citation counts for clinical articles at two years using data available within three weeks of publication: retrospective cohort study BMJ, 2008;336:655-657

Moed, H. F. (2005) Statistical Relationships Between Downloads and Citations at the Level of Individual Documents Within a Single Journal. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 56(10): 1088- 1097

O'Leary, D. E. (2008) The relationship between citations and number of downloads Decision Support Systems 45(4): 972-980

Watson, A. B. (2009) Comparing citations and downloads for individual articles Journal of Vision 9(4): 1-4

Thursday, January 7. 2010

Log Ratios, Effect Size, and a Mandated OA Advantage?

Update Feb 8, 2010: See also "Open Access: Self-Selected, Mandated & Random; Answers & Questions"

Phil Davis: "An interesting bit of research, although I have some methodological concerns about how you treat the data, which may explain some inconsistent and counter-intuitive results, see: http://j.mp/8LK57u A technical response addressing the methodology is welcome."Thanks for the feedback. We reply to the three points of substance, in order of importance:

(1) LOG RATIOS: We analyzed log citation ratios to adjust for departures from normality. Logs were used to normalize the citations and attenuate distortion from high values. Moed's (2007) point was about (non-log) ratios that were not used in this study. We used log citation ratios. This approach loses some values when the log tranformation makes the denominator zero, but despite these lost data, the t-test results were significant, and were further confirmed by our second, logistic regression analysis. It is highly unlikely that any of this would introduce a systematic bias in favor of OA, but if the referees of the paper should call for a "simpler and more elegant" analysis to make sure, we will be glad to perform it.

(2) EFFECT SIZE: The size of the OA Advantage varies greatly from year to year and field to field. We reported this in Hajjem et al (2005), stressing that the important point is that there is virtually always a positive OA Advantage, absent only when the sample is too small or the effect is measured too early (as in Davis et al's 2008 study). The consistently bigger OA Advantage in physics (Brody & Harnad 2004) is almost certainly an effect of the Early Access factor, because in physics, unlike in most other disciplines (apart from computer science and economics), authors tend to make their unrefereed preprints OA well before publication. (This too might be a good practice to emulate, for authors desirous of greater research impact.)

(3) MANDATED OA ADVANTAGE? Yes, the fact that the citation advantage of mandated OA was slightly greater than that of self-selected OA is surprising, and if it proves reliable, it is interesting and worthy of interpretation. We did not interpret it in our paper, because it was the smallest effect, and our focus was on testing the Self-Selection/Quality-Bias hypothesis, according to which mandated OA should have little or no citation advantage at all, if self-selection is a major contributor to the OA citation advantage.

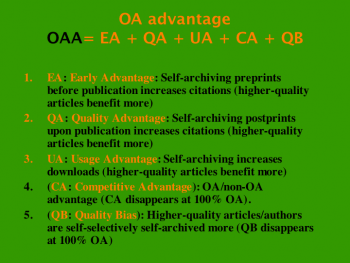

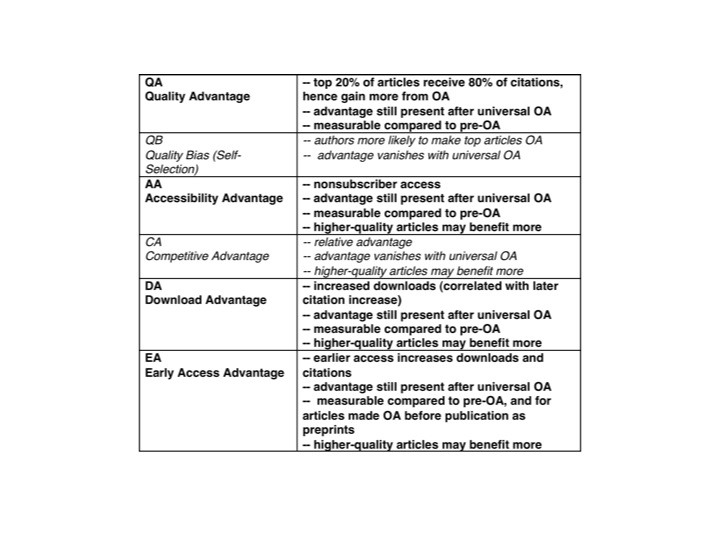

Our sample was 2002-2006. We are now analyzing 2007-2008. If there is still a statistically significant OA advantage for mandated OA over self-selected OA in this more recent sample too, a potential explanation is the inverse of the Self-Selection/Quality-Bias hypothesis (which, by the way, we do think is one of the several factors that contribute to the OA Advantage, alongside the other contributors: Early Advantage, Quality Advantage, Competitive Advantage, Download Advantage, Arxiv Advantage, and probably others).

The Self-Selection/Quality-Bias (SSQB) consists of better authors being more likely to make their papers OA, and/or authors being more likely to make their better papers OA, because they are better, hence more citeable. The hypothesis we tested was that all or most of the widely reported OA Advantage across all fields and years is just due to SSQB. Our data show that it is not, because the OA Advantage is no smaller when it is mandated. If it turns out to be reliably bigger, the most likely explanation is a variant of the "Sitting Pretty" (SP) effect, whereby some of the more comfortable authors have said that the reason they do not make their articles OA is that they think they have enough access and impact already. Such authors do not self-archive spontaneously. But when OA is mandated, their papers reap the extra benefit of OA, with its Quality Advantage (for the better, more citeable papers). In other words, if SSQB is a bias in favor of OA on the part of some of the better authors, mandates reverse an SP bias against OA on the part of others of the better authors. Spontaneous, unmandated OA would be missing the papers of these SP authors.

There may be other explanations too. But we think any explanation at all is premature until it is confirmed that this new mandated OA advantage is indeed reliable and replicable. Phil further singles out the fact that the mandate advantage is present in the middle citation ranges and not the top and bottom. Again, it seems premature to interpret these minor effects whose unreliability is unknown, but if forced to pick an interpretation now, we would say it was because the "Sitting Pretty" authors may be the middle-range authors rather than the top ones...

Brody, T. and Harnad, S. (2004) Comparing the Impact of Open Access (OA) vs. Non-OA Articles in the Same Journals. D-Lib Magazine 10(6).Yassine Gargouri, Chawki Hajjem, Vincent Lariviere, Yves Gingras, Les Carr, Tim Brody, Stevan Harnad

Davis, P.M., Lewenstein, B.V., Simon, D.H., Booth, J.G., Connolly, M.J.L. (2008) Open access publishing, article downloads, and citations: randomised controlled trial British Medical Journal 337:a568

Hajjem, C., Harnad, S. and Gingras, Y. (2005) Ten-Year Cross-Disciplinary Comparison of the Growth of Open Access and How it Increases Research Citation Impact. IEEE Data Engineering Bulletin 28(4) 39-47.

Moed, H. F. (2006) The effect of 'Open Access' upon citation impact: An analysis of ArXiv's Condensed Matter Section Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 58(13) 2145-2156

Tuesday, November 17. 2009

On Self-Selection Bias In Publisher Anti-Open-Access Lobbying

Response to Comment by Ian Russell on Ann Mroz's 12 November 2009 editorial "Put all the results out in the open" in Times Higher Education:

Update Jan 1, 2010: See Gargouri, Y; C Hajjem, V Larivière, Y Gingras, L Carr,T Brody & S Harnad (2010) “Open Access, Whether Self-Selected or Mandated, Increases Citation Impact, Especially for Higher Quality Research”

Update Feb 8, 2010: See also "Open Access: Self-Selected, Mandated & Random; Answers & Questions"

"It’s not 'lobbying from subscription publishers' that has stalled open access, it’s the realization that the simplistic arguments of the open access lobby don’t hold water in the real world... [with] open access lobbyists constantly referring to the same biased and dubious ‘evidence’ (much of it not in the peer reviewed literature)."Please stay tuned for more peer-reviewed evidence on this, but for now note only that the study Ian Russell selectively singles out as not "biased or dubious" -- the "first randomized trial" (Davis et al 2008), which found that "Open access [OA] articles were no more likely to be cited than subscription access articles in the first year after publication” -- is the study that argued that in the host of other peer-reviewed studies that have kept finding OA articles to be more likely to be cited (the effect usually becoming statistically significant not during but after the first year), the OA advantage (according to Davis et al) is simply a result of a self-selection bias on the part of their authors: Authors selectively make their better (hence more citeable) articles OA.

Russell selectively cites only this negative study -- the overhastily (overoptimistically?) published first-year phase of a still ongoing three-year study by Davis et al -- because its result sounds more congenial to the publishing lobby. Russell selectively ignores as "biased and dubious" the many positive (peer-reviewed) studies that do keep finding the OA advantage, as well as the critique of this negative study (as having been based on too short a time interval and too small a sample, not even long enough to replicate the widely reported effect that it was attempting to demonstrate to be merely an artifact of a self-selection bias). Russell also selectively omits to mention that even the Davis et al study found an OA advantage for downloads within the first year -- with other peer-reviewed studies having found that a download advantage in the first year translates into a citation advantage in the second year (e.g., Brody et al 2006). (If one were uncharitable, one might liken this sort of self-serving selectivity to that of the tobacco industry lobby in its time of tribulation, but here it is not public health that is at stake, merely research impact...)

But fair enough. We've now tested whether the self-selected OA impact advantage is reduced or eliminated when the OA is mandated rather than self-selective. The results will be announced as soon as they have gone through peer review. Meanwhile, place your bets...

Brody, T., Harnad, S. and Carr, L. (2006) Earlier Web Usage Statistics as Predictors of Later Citation Impact. Journal of the American Association for Information Science and Technology (JASIST) 57(8) pp. 1060-1072.

Davis, PN, Lewenstein, BV, Simon, DH, Booth, JG, & Connolly, MJL (2008) Open access publishing, article downloads, and citations: randomised controlled trial British Medical Journal 337: a568

Harnad, S. (2008) Davis et al's 1-year Study of Self-Selection Bias: No Self-Archiving Control, No OA Effect, No Conclusion.

Hitchcock, S. (2009) The effect of open access and downloads ('hits') on citation impact: a bibliography of studies.

Tuesday, November 10. 2009

OA's Continuing Misadventures: Columbia the 4th to Buy Pyrite Instead of First Sowing Green

Ironically, I'll have to leave it to Phil Davis (of the Society for Scholarly Publishing's "Scholarly Kitchen") to flesh out the futility and fatuity of this latest outbreak of pre-emptive gold fever.

Ironically, I'll have to leave it to Phil Davis (of the Society for Scholarly Publishing's "Scholarly Kitchen") to flesh out the futility and fatuity of this latest outbreak of pre-emptive gold fever. (Only known antidote: Green OA Mandates, which Harvard and MIT had had the good sense and foresight to adopt first, before signing on to COPE; Columbia instead shadows the somnambulism of Cornell, Dartmouth and Berkeley.)

SSP (and STM and AAP and ALPSP) have been handed (on a gold platter) yet another free ingredient with which to roast OA.

Meanwhile, as we keep fiddling, our access and impact keep burning.

Thursday, September 17. 2009

Fund Gold OA Only AFTER Mandating Green OA, Not INSTEAD

"If the creation of a funding line to support a particular form of publishing is designed as a hypothesis, what result are they expecting? What constitutes a successful or failed experiment?... If this is about access, let’s talk about whether this type of publishing results in disseminating scientific results to more readers. If this debate is about economics, let’s talk about whether Cornell and the four other signatory institutions will save money under this model."Underlying the proposed “Compact” is the usual conflation of the access problem with the affordability problem, as well as the conflation of their respective solutions: Green OA self-archiving and Gold OA publishing.

Open Access (OA) is about access, not about journal economics. The journal affordability problem is only relevant (to OA) inasmuch as it reduces access; and Gold OA publishing is only relevant (to OA) inasmuch as it increases access -- which for a given university, is not much (today): Authors must remain free to publish in their journal of choice. Most refereed journals are not Gold OA journals today. Nor could universities afford to pay Gold OA fees for the publication of all or most of their authors' research output today, because universities are already paying for publication via their subscription fees today.

Hence the only measure of the success of a university's OA policy (for OA) is the degree to which it provides OA to the university's own research article output. By that measure, a Gold OA funding compact provides OA to the fraction of a university's total research output for which there exist Gold OA journals today that are suitable to the author and affordable to the university today. That fraction will vary with the institution, but it will always be small (today).

In contrast, a Green OA self-archiving mandate provides OA to most or all of a university's research article output within two years of adoption.

There are 5 signatories to the Gold OA "Compact" so far. Two of them (Harvard and MIT) have already mandated Green OA, so what they go on to do with their available funds does not matter here, one way or the other.

The other three signatories (Cornell, Dartmouth and Berkeley), however, have not yet mandated Green OA. As such, their "success" in providing OA to their own research article output will not only be minimal, but they will be setting an extremely bad example for other universities, who may likewise decide that they are doing their part for OA by signing this compact for Gold OA (in exchange for next to no OA, at a high cost) instead of mandating Green OA (in exchange for OA to most or all their research articles output, at next to no extra cost).

What universities, funders, researchers and research itself need, urgently, is Green OA mandates, not Gold OA Compacts. Mandate Green OA first, and then compact to do whatever you like with your spare cash. But on no account commit to spending it pre-emptively on funding Gold OA instead of mandating Green OA -- not if OA is your goal, rather than something else.

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Tuesday, February 24. 2009

The Evans & Reimer OA Impact Study: A Welter of Misunderstandings

Update Jan 1, 2010: See Gargouri, Y; C Hajjem, V Larivière, Y Gingras, L Carr,T Brody & S Harnad (2010) “Open Access, Whether Self-Selected or Mandated, Increases Citation Impact, Especially for Higher Quality Research”

Update Feb 8, 2010: See also "Open Access: Self-Selected, Mandated & Random; Answers & Questions"

Basken, Paul (2009) Fee-Based Journals Get Better Results, Study in Fee-Based Journal Reports. Chronicle of Higher Education February 23, 2009(Re: Paul Basken) No, the Evans & Reimer (E & R) study in Science does not show that

"researchers may find a wider audience if they make their findings available through a fee-based Web site rather than make their work freely available on the Internet."This is complete nonsense, since the "fee-based Web site" is immediately and fully accessible -- to all those who can and do pay for access in any case. (It is simply the online version of the journal; for immediate permanent access to it, an individual or institution pays a subscription or license fee.) The free version is extra: a supplement to that fee-based online version, not an alternative to it: it is provided for those would-be users who cannot afford the access-fee. In E & R's study, the free access is provided -- after an access-embargo of up to a year or more -- by the journal itself. In studies by others, the free access is provided by the author, depositing the final refereed draft of the article on his own website, free for all (usually immediately, with no prior embargo). E & R did not examine the latter form of free online access at all. (Paul Basken has confused (1) the size of the benefits of fee-based online access over fee-based print-access alone with (2) the size of the benefits of free online access over fee-based online-access alone. The fault is partly E & R's for describing their findings in such an equivocal way.)

(Re: Phil Davis) No, E & R do not show that

"the effect of OA on citations may be much smaller than originally reported."E & R show that the effect of free access on citations after an access-embargo (fee-based access only) of up to a year or longer is much smaller than the effect of the more immediate OA that has been widely reported.

(Re: Phil Davis) No, E & R do not show that

"the vast majority of freely-accessible scientific articles are not published in OA journals, but are made freely available by non-profit scientific societies using a subscription model."E & R did not even look at the vast majority of current freely-accessible articles (per year), which are the ones self-archived by their authors. E & R looked only at journals that make their entire contents free after an access-embargo of up to a year or more. (Cumulative back-files will of course outnumber any current year, but what current research needs, especially in fast-moving fields, is immediate access to current, ongoing research, not just legacy research.)

See: "Open Access Benefits for the Developed and Developing World: The Harvards and the Have-Nots"

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Thursday, February 19. 2009

Open Access Benefits for the Developed and Developing World: The Harvards and the Have-Nots

Update Jan 1, 2010: See Gargouri, Y; C Hajjem, V Larivière, Y Gingras, L Carr,T Brody & S Harnad (2010) “Open Access, Whether Self-Selected or Mandated, Increases Citation Impact, Especially for Higher Quality Research”

Update Feb 8, 2010: See also "Open Access: Self-Selected, Mandated & Random; Answers & Questions"

The portion of Evans & Reimer's (2009) study (E & R) is valid is timely and useful, showing that a large portion of the Open Access citation impact advantage comes from providing the developing world with access to the research produced by the developed world. Using a much bigger database, E & R refute (without citing!) a recent flawed study (Frandsen 2009) that reported that there was no such effect (as well as a premature response hailing it as "Open Access: No Benefit for Poor Scientists").

SUMMARY: Evans & Reimer (2009) (E & R) show that a large portion of the increased citations generated by making articles freely accessible online ("Open Access," OA) comes from Developing-World authors citing OA articles more.It is very likely that a within-US comparison based on the same data would show much the same effect: making articles OA should increase citations from authors at the Have-Not universities (with the smaller journal subscription budgets) more than from Harvard authors. Articles by Developing World (and US Have-Not) authors should also be cited more if they are made OA, but the main beneficiaries of OA will be the best articles, wherever they are published. This raises the question of how many citations – and how much corresponding research uptake, usage, progress and impact – are lost when articles are embargoed for 6-12 months or longer by their publishers against being made OA by their authors.

(It is important to note that E & R's results are not based on immediate OA but on free access after an embargo of up to a year or more. Theirs is not an estimate of the increase in citation impact that results from immediate Open Access; it is just the increase that results from ending Embargoed Access. In a fast-moving field of science, an access lag of a year can lose a lot of research impact, permanently.)

E & R found the following. (Their main finding is number #4):

#1 When articles are made commercially available online their citation impact becomes greater than when they were commercially available only as print-on-paper. (This is unsurprising, since online access means easier and broader access than just print-on-paper access.)

#2 When articles are made freely available online their citation impact becomes greater than when they were not freely available online. (This confirms the widely reported "Open Access" (OA) Advantage.)

(E & R cite only a few other studies that have previously reported the OA advantage, stating that those were only in a few fields, or within just one journal. This is not correct; there have been many other studies that likewise reported the OA advantage, across nearly as many journals and fields as E & R sampled. E & R also seem to have misunderstood the role of prepublication preprints in those fields (mostly physics) that effectively already have post-publication OA. In those fields, all of the OA advantage comes from the year(s) before publication -- "the Early OA Advantage", which is relevant to the question, raised below, about the harmful effects of access embargoes. And last, E&R cite the few negative studies that have been published -- mostly the deeply flawed studies of Phil Davis -- that found no OA Advantage or even a negative effect (as if making papers freely available reduced their citations!).#3 The citation advantage of commercial online access over commercial print-only access is greater than the citation advantage of free access over commercial print plus online access only. (This too is unsurprising, but it is also somewhat misleading, because virtually all journals have commercial online access today: hence the added advantage of free online access is something that occurs over and above mere online (commercial) access -- not as some sort of competitor or alternative to it! The comparison today is toll-based online access vs. free online access.)

(There may be some confusion here between the size of the OA advantage for journals whose contents were made free online after a pospublication embargo period, versus those whose contents were made free online immediately upon publication -- i.e., the OA journals. Commercial online access is of course never embargoed: you get access as soon as its paid for! Previous studies have made within-journal comparisons, field by field, between OA and non-OA articles within the same journal and year. These studies found much bigger OA Advantages because they were comparing like with like and because they were based on a longer time-span: The OA advantage is still small after only a year, because it takes time for citations to build up; this is even truer if the article becomes "OA" only after it has been embargoed for a year or longer!)#4 The OA Advantage is far bigger in the Developing World (i.e., Developing-World first-authors, when they cite OA compared to non-OA articles). This is the main finding of this article, and this is what refutes the Frandsen study.

What E & R have not yet done (and should!) is to check for the very same effect, but within the Developed World, by comparing the "Harvards vs. the Have-Nots" within, say the US: The ARL has a database showing the size of the journal holdings of most research university libraries in the US. Analogous to their comparison's between Developed and Developing countries, E & R could split the ARL holdings into 10 deciles, as they did with the wealth (GNI) of countries. I am almost certain this will show that a large portion of the OA impact advantage in the US comes from the US's "Have-Nots", compared to its Harvards.

The other question is the converse: The OA advantage for articles authored (rather than cited) by Developing World authors. OA does not just give the Developing World more access to the input it needs (mostly from the Developed World), as E & R showed; but OA also provides more impact for the Developing World's research output, by making it more widely accessible (to both the Developing and Developed world) -- something E & R have not yet looked at either, though they have the data! Because of what Seglen (1992) called the "skewness of science," however, the biggest beneficiaries of OA will of course be the best articles, wherever their authors: 90% of citations go to the top 10% of articles.

Last, there is the crucial question of the effect of access embargoes. It is essential to note that E & R's results are not based on immediate OA but on free access after an embargo of up to a year or more. Theirs is hence not an estimate of the increase in citation impact that results from immediate Open Access; it is just the increase that results from ending Embargoed Access.

It will be important to compare the effect of OA on embargoed versus unembargoed content, and to look at the size of the OA Advantage after an interval of longer than just a year. (Although early access is crucial in some fields, citations are not instantaneous: it may take a few years' work to generate the cumulative citation impact of that early access. But it is also true in some fast-moving fields that the extra momentum lost during a 6-12-month embargo is never really recouped.)

Evans, JA & Reimer, J. (2009) Open Access and Global Participation in Science Science 323(5917) (February 20 2009)Stevan Harnad

Hajjem, C., Harnad, S. and Gingras, Y. (2005) Ten-Year Cross-Disciplinary Comparison of the Growth of Open Access and How it Increases Research Citation Impact. IEEE Data Engineering Bulletin 28(4) pp. 39-47.

Seglen PO (1992) The skewness of science. Journal of the American Society for Information Science 43:628-38

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Wednesday, January 14. 2009

Comparing OA/non-OA in Developing Countries

"[A]n investigation of the use of open access by researchers from developing countries... show[s] that open access journals are not characterised by a different composition of authors than the traditional toll access journals... [A]uthors from developing countries do not cite open access more than authors from developed countries... [A]uthors from developing countries are not more attracted to open access than authors from developed countries. [underscoring added]"(Frandsen 2009, J. Doc. 65(1))Open Access is not the same thing as Open Access Journals.

(See also "Open Access: No Benefit for Poor Scientists")

Articles published in conventional non-Open-Access journals can also be made Open Access (OA) by their authors -- by self-archiving them in their own Institutional Repositories.

The Frandsen study focused on OA journals, not on OA articles. It is problematic to compare OA and non-OA journals, because journals differ in quality and content, and OA journals tend to be newer and fewer than non-OA journals (and often not at the top of the quality hierarchy).

Some studies have reported that OA journals are cited more, but because of the problem of equating journals, these findings are limited. In contrast, most studies that have compared OA and non-OA articles within the same journal and year have found a significant citation advantage for OA. It is highly unlikely that this is only a developed-world effect; indeed it is almost certain that a goodly portion of OA's enhanced access, usage and impact comes from developing-world users.

It is unsurprising that developing world authors are hesitant about publishing in OA journals, as they are the least able to pay author/institution publishing fees (if any). It is also unsurprising that there is no significant shift in citations toward OA journals in preference to non-OA journals (whether in the developing or developed world): Accessibility is a necessary -- not a sufficient -- condition for usage and citation: The other necessary condition is quality. Hence it was to be expected that the OA Advantage would affect the top quality research most. That's where the proportion of OA journals is lowest.

The Seglen effect ("skewness of science") is that the top 20% of articles tend to receive 80% of the citations. This is why the OA Advantage is more detectable by comparing OA and non-OA articles within the same journal, rather than by comparing OA and non-OA journals.

We will soon be reporting results showing that the within-journal OA Advantage is higher in "higher-impact" (i.e., more cited) journals. Although citations are not identical with quality, they do correlate with quality (when comparing like with like). So an easy way to understand the OA Advantage is as a quality advantage -- with OA "levelling the playing field" by allowing authors to select which papers to cite on the basis of their quality, unconstrained by their accessibility. This effect should be especially strong in the developing world, where access-deprivation is greatest.

Leslie Chan -- "Associate Director of Bioline International, co-signatory of the Budapest Open Access Initiative, supervisor in the new media and international studies programs at the University of Toronto, and tireless champion for the needs of the developing world" (Poynder 2008) -- has added the following in the American Scientist Open Access Forum:I concur with Stevan's comments, and would like to add the following:

1. From our perspective, OA is as much about the flow of knowledge from the South to the North as much as the traditional concern with access to literature from the North. So the question to ask is whether with OA, authors from the North are starting to cite authors from the South. This is a study we are planning. We already have good evidence that more authors from the North are publishing in OA journals in the South (already an interesting reversal) but we need a more careful analysis of the citation data.

2. The more critical issue regarding OA and developing country scientists is that most of those who publish in "international" journals cannot access their own publications. This is where open repositories are crucial, to provide access to research from the South that is otherwise inaccessible.

3. The Frandsen study focuses on biology journals and I am not sure what percentage of them are available to DC researchers through HINARI/AGORA. This would explain why researchers in this area would not need to rely on OA materials as much. But HINARI etc. are not OA programs, and local researchers will be left with nothing when the programs are terminated. OA is the only sustainable way to build local research capacity in the long term.

4. Norris et. al's (2008) "Open access citation rates and developing countries" focuses instead on Mathematics, a field not covered by HINARI and they conclude that "the majority of citations were given by Americans to Americans, but the admittedly small number of citations from authors in developing countries do seem to show a higher proportion of citations given to OA articles than is the case for citations from developed countries. Some of the evidence for this conclusion is, however, mixed, with some of the data pointing toward a more complex picture of citation behaviour."

5. Citation behaviour is complex indeed and more studies on OA's impact in the developing world are clearly needed. Davis's eagerness to pronounce that there is "No Benefit for Poor Scientists" based on one study is highly premature.

If there should be a study showing that people in developing countries prefer imported bottled water over local drinking water, should efforts to ensure clean water supplies locally be questioned?

Leslie Chan

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Monday, August 25. 2008

Confirmation Bias and the Open Access Advantage: Some Methodological Suggestions for Davis's Citation Study

Update Jan 1, 2010: See Gargouri, Y; C Hajjem, V Larivière, Y Gingras, L Carr,T Brody & S Harnad (2010) “Open Access, Whether Self-Selected or Mandated, Increases Citation Impact, Especially for Higher Quality Research”

Update Feb 8, 2010: See also "Open Access: Self-Selected, Mandated & Random; Answers & Questions"

SUMMARY: Davis (2008) analyzes citations from 2004-2007 in 11 biomedical journals. For 1,600 of the 11,000 articles (15%), their authors paid the publisher to make them Open Access (OA). The outcome, confirming previous studies (on both paid and unpaid OA), is a significant OA citation Advantage, but a small one (21%, 4% of it correlated with other article variables such as number of authors, references and pages). The author infers that the size of the OA advantage in this biomedical sample has been shrinking annually from 2004-2007, but the data suggest the opposite. In order to draw valid conclusions from these data, the following five further analyses are necessary:

(1) The current analysis is based only on author-choice (paid) OA. Free OA self-archiving needs to be taken into account too, for the same journals and years, rather than being counted as non-OA, as in the current analysis.Davis proposes that an author self-selection bias for providing OA to higher-quality articles (the Quality Bias, QB) is the primary cause of the observed OA Advantage, but this study does not test or show anything at all about the causal role of QB (or of any of the other potential causal factors, such as Accessibility Advantage, AA, Competitive Advantage, CA, Download Advantage, DA, Early Advantage, EA, and Quality Advantage, QA). The author also suggests that paid OA is not worth the cost, per extra citation. This is probably true, but with OA self-archiving, both the OA and the extra citations are free.

(2) The proportion of OA articles per journal per year needs to be reported and taken into account.

(3) Estimates of journal and article quality and citability in the form of the Journal Impact Factor and the relation between the size of the OA Advantage and journal as well as article “citation-bracket” need to be taken into account.

(4) The sample-size for the highest-impact, largest-sample journal analyzed, PNAS, is restricted and is excluded from some of the analyses. An analysis of the full PNAS dataset is needed, for the entire 2004-2007 period.

(5) The analysis of the interaction between OA and time, 2004-2007, is based on retrospective data from a June 2008 total cumulative citation count. The analysis needs to be redone taking into account the dates of both the cited articles and the citing articles, otherwise article-age effects and any other real-time effects from 2004-2008 are confounded.

The Davis (2008) preprint is an analysis of the citations from years c. 2004-2007 in 11 biomedical journals: c. 11,000 articles, of which c. 1,600 (15%) were made Open Access (OA) through “Author Choice” (AC-OA): author chooses to pay publisher for OA). Author self-archiving (SA-OA) articles from the same journals was not measured.Comments on: Davis, P.M. (2008) Author-choice open access publishing in the biological and medical literature: a citation analysis. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology (JASIST) (in press) http://arxiv.org/pdf/0808.2428v1

The result was a significant OA citation advantage (21%) over time, of which 4% was correlated with variables other than OA and time (number of authors, pages, references; whether article is a Review and has a US co-author).

This outcome confirms the findings of numerous previous studies (some of them based on far larger samples of fields, journals, articles and time-intervals) of an OA citation advantage (ranging from 25%-250%) in all fields, across a 10-year range (Hitchcock 2008).

The preprint also states that the size of the OA advantage in this biomedical sample diminishes annually from 2004-2007. But the data seem to show the opposite: that as an article gets older, and its cumulative citations grow, its absolute and relative OA advantage grow too.

The preprint concludes, based on its estimate of the size of the OA citation Advantage, that AC-OA is not worth the cost, per extra citation. This is probably true -- but with SA-OA the OA and the extra citations can be had at no cost at all.

The paper is accepted for publication in JASIST. It is not clear whether the linked text is the unrefereed preprint, or the refereed, revised postprint. On the assumption that it is the unrefereed preprint, what follows is an extended peer commentary with recommendations on what should be done in revising it for publication.

(It is very possible, however, that some or all of these revisions were also recommended by the JASIST referees and that some of the changes have already been made in the published version.)

As it stands currently, this study (i) confirms a significant OA citation Advantage, (ii) shows that it grows cumulatively with article age and (iii) shows that it is correlated with several other variables that are correlated with citation counts.

Although the author argues that an author self-selection bias for preferentially providing OA to higher-quality articles (the Quality Bias, QB) is the primary causal factor underlying the observed OA Advantage, in fact this study does not test or show anything at all about the causal role of QB (or of any of the other potential causal factors underlying the OA Advantage, such as Accessibility Advantage, AA, Competitive Advantage, CA, Download Advantage, DA, Early Advantage, EA, and Quality Advantage, QA; Hajjem & Harnad 2007b).

The following 5 further analyses of the data are necessary. The size and pattern of the observed results, as well as their interpretations, could all be significantly altered (as well as deepened) by their outcome:

(1) The current analysis is based only on author-choice (paid) OA. Free author self-archiving OA needs to be taken into account too, for the same journals and years, rather than being counted as non-OA, as in the current analysis.Commentary on the text of the preprint:

(2) The proportion of OA articles per journal per year needs to be reported and taken into account.

(3) Estimates of journal and article quality and citability in the form of the Journal Impact Factor (journal’s average citations) and the relation between the size of the OA Advantage and journal and article “citation-bracket” need to be taken into account.

(4) The sample-size for the highest-impact, largest-sample journal, PNAS, is restricted and is excluded from some of the analyses. A full analysis of the full PNAS dataset is needed, for the entire 2004-2007 period.

(5) The analysis of the interaction between OA and time, 2004-2007, is based on retrospective data from a June 2008 total cumulative citation count. The analysis needs to be redone taking into account the dates of both the cited articles and the citing articles, otherwise article-age effects and any other real-time effects from 2004-2008 are confounded.

“ABSTRACT… there is strong evidence to suggest that the open access advantage is declining by about 7% per year, from 32% in 2004 to 11% in 2007”It is not clearly explained how these figures and their interpretation are derived, nor is it reported how many OA articles there were in each of these years. The figures appear to be based on a statistical interaction between OA and article-age in a multiple regression analysis for 9 of the 11 journals in the sample. (a) The data from PNAS, the largest and highest-impact journal, are excluded from this analysis. (b) The many variables included in the (full) multiple regression equation (across journals) omit one of the most obvious ones: journal impact factor. (c) OA articles that are self-archived rather than paid author-choice are not identified and included as OA, hence their citations are counted as being non-OA. (d) The OA/age interaction is not based on yearly citations after a fixed interval for each year, but on cumulative retrospective citations in June 2008.

The natural interpretation of Figure 1 accordingly seems to be the exact opposite of the one the author makes: Not that the size of the OA Advantage shrinks from 2004-2007, but that the size of the OA Advantage grows from 2007-2004 (as articles get older and their citations grow). Not only do cumulative citations grow for both OA and non-OA articles from year 2007 articles to year 2004 articles, but the cumulative OA advantage increases (by about 7% per year, even on the basis of this study’s rather slim and selective data and analyses).

This is quite natural, as not only do citations grow with time, but the OA Advantage -- barely detectable in the first year, being then based on the smallest sample and the fewest citations -- emerges with time.

“See Craig et al. [2007] for a critical review of the literature [on the OA citation advantage]”Craig et al’s rather slanted 2007 review is the only reference to previous findings on the OA Advantage cited by the Davis preprint (Harnad 2007a). Craig et al. had attempted to reinterpret the many times replicated positive finding of an OA citation advantage, on the basis of 4 negative findings (Davis & Fromerth, 2007; Kurtz et al., 2005; Kurtz & Henneken, 2007; Moed, 2007), in maths, astronomy and condensed matter physics, respectively. Apart from Davis’s own prior study, these studies were based mainly on preprints that were made OA well before publication. The observed OA advantage consisted mostly of an Early Access Advantage for the OA prepublication preprint, plus an inferred Quality Bias (QB) on the part of authors towards preferentially providing OA to higher quality preprints (Harnad 2007b).

The Davis preprint does not cite any of the considerably larger number of studies that have reported large and consistent OA advantages for postprints, based on many more fields, some of them based on far larger samples and longer time intervals (Hitchcock 2008). Instead, Davis focuses rather single-mindedly on the hypothesis that most or all of the OA Advantage is the result for the self-selection bias (QB) toward preferentially making higher-quality (hence more citeable) articles OA:

“authors selectively choose which articles to promote freely… [and] highly cited authors disproportionately choose open access venues”It is undoubtedly true that better authors are more likely to make their articles OA, and that authors in general are more likely to make their better articles OA. This Quality or “Self-Selection” Bias (QB) is one of the probable causes of the OA Advantage.

However, no study has shown that QB is the only cause of the OA Advantage, nor even that it is the biggest cause. Three of the studies cited (Kurtz et al., 2005; Kurtz & Henneken, 2007; Moed, 2007) showed that another causal factor is Early Access (EA: providing OA earlier results in more citations).

There are several other candidate causal factors in the OA Advantage, besides QB and EA (Hajjem & Harnad 2007b):

There is the Download (or Usage) Advantage (DA): OA articles are downloaded significantly more, and this early DA has also been shown to be predictive of a later citation advantage in Physics (Brody et al. 2006).

There is the Download (or Usage) Advantage (DA): OA articles are downloaded significantly more, and this early DA has also been shown to be predictive of a later citation advantage in Physics (Brody et al. 2006).There is a Competitive Advantage (CA): OA articles are in competition with non-OA articles, and to the extent that OA articles are relatively more accessible than non-OA articles, they can be used and cited more. Both QB and CA, however, are temporary components of the OA advantage that will necessarily shrink to zero and disappear once all research is OA. EA and DA, in contrast, will continue to contribute to the OA advantage even after universal OA is reached, when all postprints are being made OA immediately upon publication, compared to pre-OA days (as Kurtz has shown for Astronomy, which has already reached universal post-publication OA).

There is an Accessibility Advantage (AA) for those users whose institutions do not have subscription access to the journal in which the article appeared. AA too (unlike CA) persists even after universal OA is reached: all articles then have AA's full benefit.

And there is at least one more important causal component in the OA Advantage, apart from AA, CA, DA and QB, and that is a Quality Advantage (QA), which has often been erroneously conflated with QB (Quality Bias):

Ever since Lawrence’s original study in 2001, the OA Advantage can be estmated in two different ways: (1) by comparing the average citations for OA and non-OA articles (log citation ratios within the same journal and year, or regression analyses like Davis’s) and (2) by comparing the proportion of OA articles in different “citation brackets” (0, 1, 2, 3-4, 5-8, 9-16, 17+ citations).

In method (2), the OA Advantage is observed in the form of an increase in the proportion of OA articles in the higher citation brackets. But this correlation can be explained in two ways. One is QB, which is that authors are more likely to make higher-quality articles OA. But it is also at least as plausible that higher-quality articles benefit more from OA! It is already known that the top c. 10-20% of articles receive c. 80-90% of all citations (Seglen’s 1992 “skewness of science”). It stands to reason, then, that when all articles are made OA, it is the top 20% of articles that are most likely to be cited more: Not all OA articles benefit from OA equally, because not all articles are of equally citable quality.

Hence both QB and QA are likely to be causal components in the OA Advantage, and the only way to tease them apart and estimate their individual contributions is to control for the QB effect by imposing the OA instead of allowing it to be determined by self-selection. We (Gargouri, Hajjem, Gingras, Carr & Harnad, in prep.) are completing such a study now, comparing mandated and unmandated OA; and Davis et al 2008 have just published another study on randomized OA for 11 journals:

“In the first controlled trial of open access publishing where articles were randomly assigned to either open access or subscription-access status, we recently reported that no citation advantage could be attributed to access status (Davis, Lewenstein, Simon, Booth, & Connolly, 2008)”This randomized OA study by Davis et al. was very welcome and timely, but it had originally been announced to cover a 4-year period, from 2007-2010, whereas it was instead prematurely published in 2008, after only one year. No OA advantage at all was observed in that 1-year interval, and this too agrees with the many existing studies on the OA Advantage, some based on far larger samples of journals, articles and fields: Most of those studies (none of them randomized) likewise detected no OA citation advantage at all in the first year: It is simply too early. In most fields, citations take longer than a year to be made, published, ISI-indexed and measured, and to make any further differentials (such as the OA Advantage) measurable. (This is evident in Davis’s present preprint too, where the OA advantage is barely visible in the first year (2007).)

The only way the absence of a significant OA advantage in a sample with randomized OA can be used to demonstrate that the OA Advantage is only or mostly just a self-selection bias (QB) is by also demonstrating the presence of a significant OA advantage in the same (or comparable) sample with nonrandomized (i.e., self-selected) OA.

But Davis et al. did not do this control comparison (Harnad 2008b). Finding no OA Advantage with randomized OA after one year merely confirms the (widely observed) finding that one year is usually too early to detect any OA Advantage; but it shows nothing whatsoever about self-selection QB.

“we examine the citation performance of author-choice open access”It is quite useful and interesting to examine citations for OA and non-OA articles where the OA is provided through (self-selected) “Author-Choice” (i.e., authors paying the publisher to make the article OA on the publisher’s website).

Most prior studies of the OA citation Advantage, however, are based on free self-archiving by authors on their personal, institutional or central websites. In the bigger studies, a robot trawls the web using ISI bibliographic metadata to find which articles are freely available on the web (Hajjem et al. 2005).

Hence a natural (indeed essential) control test that has been omitted from Davis’s current author-choice study – a test very much like the control test omitted from the Davis et al randomized OA study – is to identify the articles in the same sample that were made OA through author self-archiving. If those articles are identified and counted, that not only provides an estimate of the relative uptake of author-choice OA vs OA self-archiving in the same sample interval, but it allows a comparison of their respective OA Advantages. More important, it corrects the estimate of an OA Advantage based on author-choice OA alone: For, as Davis has currently done the analysis, any OA Advantage from OA self-archiving in this sample would in fact reduce the estimate of the OA Advantage based on author-choice OA (mistakenly counting as non-OA the articles and citation-counts for self-archived OA articles)

“METHODS… The uptake of the open access author-choice programs for these [11] journals ranged from 5% to 22% over the dates analyzed”Davis’s preprint does not seem to provide the data – either for individual journals or for the combined totals – on the percentage of author-choice OA (henceforth AC-OA) by year, nor on the relation between the proportion uptake of AC-OA and the size of the OA Advantage, by year.

As Davis has been careful to do multiple regression analyses on many of the article-variables that might correlate with citations and OA (article age, number of authors, number of references, etc.), it seems odd not to take into account the relation between the size of the AC-OA Advantage and the degree of uptake of AC-OA, by year. The other missing information is the corresponding data for self-archiving OA (henceforth SA-OA).

“[For] All of the journals… all articles roll into free access after an initial period [restricted to subscription access only for 12 months (8 journals), 6 months (2 journals) or 24 months (1 journal)]”(This is important in relation to the Early Access (EA) Advantage, which is the biggest contributor to the OA Advantage in the two cited studies by Kurtz on Astronomy. Astronomy has free access to the postprints of all articles in all astronomy journals immediately upon publication. Hence Astronomy has scope for an OA Advantage only through an EA Advantage, arising from the early posting of preprints before publication. The size of the OA Advantage in other fields -- in which (unlike in Astronomy) access to the postprint is restricted to subscribers-only for 6, 12, or 24 months -- would then be the equivalent of an estimate of an “EA Advantage” for those potential users who lack subscription access – i.e., the Accessibility Advantage, AA.)

“Cumulative article citations were retrieved on June 1, 2008. The age of the articles ranged from 18 to 57 months”Most of the 11 journals were sampled till December 2007. That would mean that the 2007 OA Advantage was based on even less than one year from publication.

“STATISTICAL ANALYSIS… Because citation distributions are known to be heavily skewed (Seglen, 1992) and because some of the articles were not yet cited in our dataset, we followed the common practice of adding one citation to every article and then taking the natural log”(How well did that correct the skewness? If it still was not normal, then citations might have to be dichotomized as a 0/1 variable, comparing, by citation-bracket slices, (1) 0 citations vs 1 or more citations, (2) 0 or 1 vs more than 1, (3) 2 or fewer vs. more than 2, (4) 3 or fewer vs. more than 3… etc.)

“For each journal, we ran a reduced [2 predictor] model [article age and OA] and a full [7 predictor] regression model [age, OA; log no. of authors, references, pages; Review; US author]”Both analyses are, of course, a good idea to do, but why was Journal Impact Factor (JIF) not tested as one of the predictor variables in the cross-journal analyses (Hajjem & Harnad 2007a)? Surely JIF, too, correlates with citations: Indeed, the Davis study assumes as much, as it later uses JIF as the multiplier factor in calculating the cost per extra citation for author-choice OA (see below).

Analyses by journal JIF citation-bracket, for example, can provide estimates of QA (Quality Advantage) if the OA Advantage is bigger in the higher journal citation-brackets. (Davis’s study is preoccupied with the self-selection QB bias, which it does not and cannot test, but it fails to test other candidate contributors to the OA Advantage that it can test.)

(An important and often overlooked logical point should also be noted about the correlates of citations and the direction of causation: The many predictor variables in the multiple regression equations predict not only the OA citation Advantage; they also predict citation counts themselves. It does not necessarily follow from the fact that, say, longer articles are more likely to be cited that article length is therefore an artifact that must be factored out of citation counts in order to get a more valid estimate of how accurately citations measure quality. One possibility is that length is indeed an artifact. But the other possibility is that length is a valid causal factor in quality! If length is indeed an artifact, then longer articles are being cited more just because they are longer, rather than because they are better, and this length bias needs to be subtracted out of citation counts as measures of quality. But if the extra length is a causal contributor to what makes the better articles better, then subtracting out the length effect simply serves to make citation counts a blunter, not a sharper instrument for measuring quality. The same reasoning applies to some of the other correlates of citation counts, as well as their relation to the OA citation Advantage. Systematically removing them all, even if they are not artifactual, systematically divests citation counts of their potential power to predict quality. This is another reason why citation counts need to be systematically validated against other evaluative measures [Harnad 2008a].)

“Because we may lack the statistical power to detect small significant differences for individual journals, we also analyze our data on an aggregate level”It is a reasonable, valid strategy, to analyze across journals. Yet this study still persists in drawing individual-journal level conclusions, despite having indicated (correctly) that its sample may be too small to have the power to detect individual-journal level differences (see below).

(On the other hand, it is not clear whether all the OA/non-OA citation comparisons were always within-journal, within-year, as they ought to be; no data are presented for the percentage of OA articles per year, per journal. OA/non-OA comparisons must always be within-journal/year comparisons, to be sure to compare like with like.)

“The first model includes all 11 journals, and the second omits the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), considering that it contributed nearly one-third (32%) of all articles in our dataset”Is this a justification for excluding PNAS? Not only was the analysis done with and without PNAS, but, unlike all the other journals, whose data were all included, for the entire time-span, PNAS data were only included from the first and last six months.

Why? PNAS is a very high impact factor journal, with highly cited articles. A study of PNAS alone, with its much bigger sample size, would be instructive in itself – and would almost certainly yield a bigger OA Advantage than the one derived from averaging across all 11 journals (and reducing the PNAS sample size, or excluding PNAS altogether).

There can be a QB difference between PNAS and non-PNAS articles (and authors), to be sure, because PNAS publishes articles of higher quality. But a within-PNAS year-by-year comparison of OA and non-OA that yielded a bigger OA Advantage than a within-journal OA/non-OA comparison for lower-quality journals would also reflect the contribution of QA. (With these data in hand, the author should not be so focused on confirming his hypotheses: take the opportunity to falsify them too!)

“we are able to control for variables that are well-known to predict future citations [but] we cannot control for the quality of an article”This is correct. One cannot control for the quality of an article; but in comparing within a journal/year, one can compare the size of the OA Advantage for higher and lower impact journals; if the advantage is higher for higher-impact journals, that favors QA over QB.

One can also take target OA and non-OA articles (within each citation bracket), and match the title words of each target article with other articles (in the same journal/year):

If one examines N-citation OA articles and N-citation non-OA articles, are their title-word-matched (non-OA) control articles equally likely to have N or more citations? Or are the word-matched control articles for N-citation OA articles less likely to have N or more citations than the controls for N-citation non-OA articles (which would imply that the OA has raised the OA article’s citation bracket)? And would this effect be greater in the higher citation brackets than in the lower ones (N = 1 to N = >16)?

If one is resourceful, there are ways to control, or at least triangulate on quality indirectly.

“spending a fee to make one’s article freely available from a publisher’s website may indicate there is something qualitatively different [about that article]”Yes, but one could probably tell a Just-So story either way about the direction of that difference: paying for OA because one thinks one's article is better, or paying for OA because one thinks one's article worse! Moreover, this is AC-OA, which costs money; the stakes are different with SA-OA, which only costs a few keystrokes. But this analysis omitted to identify or measure SA-OA.

“RESULTS…The difference in citations between open access and subscription-based articles is small and non-significant for the majority of the journals under investigation”(1) Compare the above with what is stated earlier: “Because we may lack the statistical power to detect small significant differences for individual journals, we also analyze our data on an aggregate level.”

(2) Davis found an OA Advantage across the entire sample of 11 journals, whereas the individual journal samples were too small. Why state this as if it were some sort of an empirical effect?

“where only time and open access status are the model predictors, five of the eleven journals show positive and significant open access effects.”(That does not sound too bad, considering that the individual journal samples were small and hence lacked the statistical power to detect small significant differences, and that the PNAS sample was made deliberately small!)

“Analyzing all journals together, we report a small but significant increase in article citations of 21%.”Whether that OA Advantage is small or big remains to be seen. The bigger published OA Advantages have been reported on the basis of bigger samples.

“Much of this citation increase can be explained by the influence of one journal, PNAS. When this journal is removed from the analysis, the citation difference reduces to 14%.”This reasoning can appeal only if one has a confirmation bias: PNAS is also the journal with the biggest sample (of which only a fraction was used); and it is also the highest impact journal of the 11 sampled, hence the most likely to show benefits from a Quality Advantage (QA) that generates more citations for higher citation-bracket articles. If the objective had not been to demonstrate that there is little or no OA Advantage (and that what little there is is just due to QB), PNAS would have been analyzed more closely and fully, rather than being minimized and excluded.

“When other explanatory predictors of citations (number of authors, pages, section, etc.) are included in the full model, only two of the eleven journals show positive and significant open access effects. Analyzing all journals together, we estimate a 17% citation advantage, which reduces to 11% if we exclude PNAS.”In other words partialling out 5 more correlated variables from this sample reduces the residual OA Advantage by 4%. And excluding the biggest, highest-quality journal’s data, reduces it still further.

If there were not this strong confirmation bent on the author’s part, the data would be treated in a rather different way: The fact that a journal with a bigger sample enhances the OA Advantage would be treated as a plus rather than a minus, suggesting that still bigger samples might have the power to detect still bigger OA Advantages. And the fact that PNAS is a higher quality journal would also be the basis for looking more closely at the role of the Quality Advantage (QA). (With less of a confirmation bent, OA Self-archiving, too, would have been controlled for, instead of being credited to non-OA.)

Instead, the awkward persistence of a significant OA Advantage even after partialling out the effects of so many correlated variables, despite restricting the size of the PNAS sample, and even after removing PNAS entirely from the analysis, has to be further explained away:

“The modest citation advantage for author-choice open access articles also appears to weaken over time. Figure 1 plots the predicted number of citations for the average article in our dataset. This difference is most pronounced for articles published in 2004 (a 32% advantage), and decreases by about 7% per year (Supplementary Table S2) until 2007 where we estimate only an 11% citation advantage.”(The methodology is not clearly described. We are not shown the percent OA per journal per year, nor what the dates of the citing articles were, for each cited-article year. What is certain is that a 1-year-old 2007 article differs from a 4-year-old 2004 article not just in its total cumulative citations in June 2008, but in that the estimate of its citations per year is based on a much smaller sample, again reducing the power of the statistic: This analysis is not based on 2005 citations to 2004 articles, plus 2006 citations to 2005 articles, plus 2007 citations to 2006 articles, etc. It is based on cumulative 2004-2008 citations to 2004, 2005, 2006 etc. articles, reckoned in June 2008. 2007 articles are not only younger: they are also more recent. Hence it is not clear what the Age/OA interaction in Table S2 really means: Has (1) the OA advantage for articles really been shrinking across those 4 years, or are citation rates for younger articles simply noisier, because based on smaller citation spans, hence (2) the OA Advantage grows more detectable as articles get older?)

From what is described and depicted in Figure 1, the natural interpretation of the Age/OA interaction seems to be the latter: As we move from one-year-old articles (2007) toward four-year-old articles, three things are happening: non-OA citations are growing with time, OA citations are growing with time, and the OA/non-OA Advantage is emerging with time.

“[To] calculate… the estimated cost per citation [$400 - $9000]… we multiply the open access citation advantage for each journal (a multiplicative effect) by the impact factor of the journal… Considering [the] strong evidence of a decline of the citation advantage over time, the cost…would be much higher…”Although these costs are probably overestimated (because the OA Advantage is underestimated, and there is no decline but rather an increase) the thrust of these figures is reasonable: It is not worth paying for AC-OA for the sake of the AC-OA Advantage: It makes far more sense to get the OA Advantage for free, through OA Self-Archiving.

Note, however, that the potentially informative journal impact factor (JIF) was omitted from the full-model multiple regression equation across journals (#6). It should be tested. So should the percentage OA for each journal/year. And after that the analysis should be redone separately for, say, the four successive JIF quartiles. If adding the JIF to the equation reduces the OA Advantage further, whereas without JIF the OA Advantage increases in each successive quartile, then that implies that a big factor in the OA Advantage is the Quality Advantage (QA).