Quicksearch

Your search for Davis returned 26 results:

Friday, September 7. 2007

Where There's No Access Problem There's No Open Access Advantage

Update Jan 1, 2010: See Gargouri, Y; C Hajjem, V Larivière, Y Gingras, L Carr,T Brody & S Harnad (2010) “Open Access, Whether Self-Selected or Mandated, Increases Citation Impact, Especially for Higher Quality Research”

Update Feb 8, 2010: See also "Open Access: Self-Selected, Mandated & Random; Answers & Questions"

Kurtz & Henneken (2007) report a very interesting new result:SUMMARY: Kurtz & Henneken (2007) report that the citation advantage of astrophysics papers self-archived as preprints in Arxiv is caused by (1) Early Advantage (EA) (earlier citations for papers self-archived earlier) and (2) Quality Bias (QB) (a self-selection bias toward self-archiving higher quality papers) and not by (3) Open Access (OA) itself (being freely accessible online to those who cannot afford subscription-toll access).

K & H suggest: "[T]here is no 'Open Access Advantage' for papers from the Astrophysical Journal" because "in a well funded field like astrophysics essentially everyone who is in a position to write research articles has full access to the literature."

This seems like a perfectly reasonable explanation for K&H's findings. Where there is no access problem, OA cannot be the cause of whatever higher citation count is observed for self-archived articles.

We (Hajjem & Harnad 2007) have conducted a similar study, but across the full spectrum of disciplines, measuring the citation advantage for mandated and unmandated self-archiving for articles from four Institutional Repositories that have self-archiving mandates, each compared to articles in the very same journal and year by authors from other institutions (on the assumption that mandated self-archiving should have less of a self-selection Quality Bias than unmandated self-archiving).

We again confirmed the citation advantage for self-archiving, and found no difference in the size of that advantage for mandated and unmandated self-archiving. It is likely that the size of the access problem differs from field to field, and with it the size of the OA citation advantage. Evidence suggests that most fields are not nearly as well-heeled as astrophysics.

"We demonstrate conclusively that there is no 'Open Access Advantage' for papers from the Astrophysical Journal. The two to one citation advantage enjoyed by papers deposited in the arXiv e-print server is due entirely to the nature and timing of the deposited papers. This may have implications for other disciplines."Earlier, Kurtz et al. (2005) had shown that the lion's share of the citation advantage of astrophysics papers self-archived as preprints in Arxiv was caused by (1) Early Advantage (EA) (earlier citations for papers self-archived earlier) and (2) Quality Bias (QB) (a self-selection bias toward self-archiving higher quality papers) and not by (3) Open Access (OA) itself (being freely accessible online to those who cannot afford subscription-toll access).

Kurtz et al. explained their finding by suggesting that:

"in a well funded field like astrophysics essentially everyone who is in a position to write research articles has full access to the literature."This seems like a perfectly reasonable explanation for their findings. Where there is no access problem, OA cannot be the cause of whatever higher citation count is observed for self-archived articles. Moed (2007) has recently reported a similar result in Condensed Matter Physics, and so have Davis & Fromerth (2007) in 4 mathematics journals.

Kurtz & Henneken's latest study confirms and strengthens their prior finding: They compared citation counts for articles published in two successive years of the Astrophysical Journal. For one of the years, the journal was freely accessible to everyone; for the other it was only accessible to subscribers. The citation counts for the self-archived articles, as expected, were twice as high as for the non-self-archived articles. They then compared the citation-counts for non-self-archived articles in the free-access year and in the toll-access year, and found no difference. They concluded, again, that OA does not cause increased citations.

But of course K&H's prior explanation -- which is that there is no access problem in astrophysics -- applies here too: It means that in a field where there is no access problem, whatever citation advantage comes from making an article OA by self-archiving cannot be an OA effect.

K&H conclude that "[t]his may have implications for other disciplines."

It should be evident, however, that the degree to which this has implications for other disciplines depends largely on the degree to which it is true in other disciplines that "essentially everyone who is in a position to write research articles has full access to the literature."

We (Hajjem & Harnad 2007) have conducted (and are currently replicating) a similar study, but across the full spectrum of disciplines, measuring the citation advantage for mandated and unmandated self-archiving for articles from 4 Institutional Repositories that have self-archiving mandates (three universities plus CERN), each compared to articles in the very same journal and year by authors from other institutions (on the assumption that mandated self-archiving should have less of a self-selection quality bias than unmandated self-archiving).

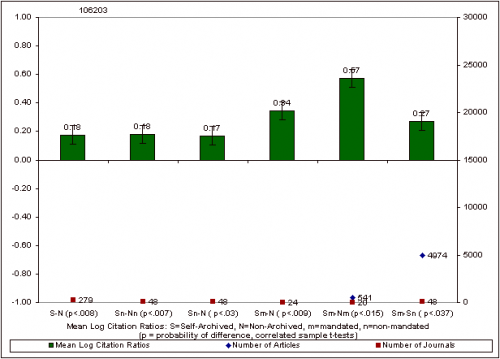

Figure 1. Self-Selected Self-Archiving vs. Mandated Self-Archiving: Within-Journal Citation Ratios (for 2004, 4 mandating institutions, all fields). S = citation counts for articles self-archived at institutions with (Sm) and without (Sn) a self-archiving mandate. N = citation counts for non-archived articles at institutions with (Nm) and without (Nn) mandate (i.e., Nm = articles not yet compliant with mandate). Grand average of (log) S/N ratios (106,203 articles; 279 journals) is the OA advantage (18%); this is about the same as for Sn/Nn (27972 articles, 48 journals, 18%) and Sn/N (17%); ratio is higher for Sm/N (34%), higher still for Sm/Nm (57%, 541 articles, 20 journals); and Sm/Sn = 27%, so self-selected self-archiving does not yield more citations than mandated (if anything, it is rather the reverse). (All six within-pair differences are significant: correlated sample t-tests.)We again confirmed the citation advantage for self-archiving, and found no difference in the size of that advantage for mandated and unmandated self-archiving. (The finding of an equally large self-archiving advantage for mandated and unmandated self-archiving was also confirmed for CERN, whose articles are all in physics -- although one could perhaps argue that CERN articles enjoy a quality advantage over articles from other institutions.)

(NB: preliminary, unrefereed results.)

A few closing points:

(1) It is likely that the size of the access problem differs from field to field, and with it the size of the OA citation advantage. Evidence suggests that most fields are not nearly as well-heeled as astrophysics. According to a JISC survey, 48% of researchers overall (biomedical sciences 53%, physical/engineering sciences 42%, social sciences 47%, language/linguistics 48% and arts/humanities 53%) have difficulty in gaining access to the resources they need to do their research. (The ARL statistics on US university serials holdings is consistent with this.) The overall access difficulty is roughly congruent with the reported OA access advantage.Stevan Harnad

(2) In Condensed Matter physics (and perhaps also mathematics) there is the further complication that it is mostly just preprints that are being self-archived, which reduces the scope for observing any postprint advantage, as opposed to just an Early Advantage (EA). (In fields that do have a significant access problem, the "Early Advantage" for postprints is the OA Advantage!) OA self-archiving mandates (and the OA movement in general) target refereed, accepted postprints, not unrefereed preprints.

(3) The positive correlation is between citation counts and the number of self-archived articles in each citation-range (Hajjem et al 2005). This could be caused by Quality Bias (QB) (higher quality articles being more likely to be self-archived) or Quality Advantage (QA) (higher quality articles benefiting more from being self-archived) or both. (The top 50% of articles tend to be cited 10 times as often as the bottom 50% [Seglen 1992]. This has nothing to do with OA or self-archiving.)

(4) Citations are of course not the only potential advantage of self-archiving. Downloads can increase too (Brody et al. 2006).

(5) We are now in the Institutional Repository (IR) era. Arxiv is a venerable Central Repository, one of the biggest and oldest and most successful of them all. But, institutions are the sources of OA content, institutions are in the best position to mandate self-archiving, and institutions share with their authors the benefits of enhancing the accessibility, usage and impact of their research output. Moreover, the nature of the web is distributed local websites, harvested by central service providers, rather than central websites.

Brody, T., Harnad, S. and Carr, L. (2006) Earlier Web Usage Statistics as Predictors of Later Citation Impact. Journal of the American Association for Information Science and Technology (JASIST) 57(8) pp. 1060-1072.

Davis, P. M. and Fromerth, M. J. (2007) Does the arXiv lead to higher citations and reduced publisher downloads for mathematics articles? Scientometics, Vol. 71, No. 2.

Hajjem, C., Harnad, S. and Gingras, Y. (2005) Ten-Year Cross-Disciplinary Comparison of the Growth of Open Access and How it Increases Research Citation Impact. IEEE Data Engineering Bulletin 28(4) pp. 39-47.

Hajjem, C. and Harnad, S. (2007) The Open Access Citation Advantage: Quality Advantage Or Quality Bias? Technical Report, Electronics and Computer Science, University of Southampton.

Kurtz, M. J. and Henneken, E. A. (2007) Open Access does not increase citations for research articles from The Astrophysical Journal. Preprint deposited in arXiv September 6, 2007.

Kurtz, M. J., Eichhorn, G., Accomazzi, A., Grant, C. S., Demleitner, M., Murray, S. S. (2005, The Effect of Use and Access on Citations. Information Processing and Management, 41, 1395-1402)

Moed, H. F. (2007) The effect of 'open access' on citation impact: An analysis of ArXiv's condensed matter section, Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology (JASIST) , August 30, 2007.

Seglen, P. O. (1992) The skewness of science. Journal of the American Society for Information Science 43:628-38

Saturday, May 26. 2007

Craig et al.'s Review of Studies on the OA Citation Advantage

Update Jan 1, 2010: See Gargouri, Y; C Hajjem, V Larivière, Y Gingras, L Carr,T Brody & S Harnad (2010) “Open Access, Whether Self-Selected or Mandated, Increases Citation Impact, Especially for Higher Quality Research”

Update Feb 8, 2010: See also "Open Access: Self-Selected, Mandated & Random; Answers & Questions"

I've read Craig et al.'s critical review concerning the OA citation impact effect and will shortly write a short, mild review. But first here is Sally Morris's posting announcing Craig et al's review, on behalf of the Publishing Research Consortium (which "proposed" the review), followed by a commentary from Bruce Royan on diglib, a few remarks from me, then commentary by JWT Smith on jisc-repositories, followed by my response, and, last, a commentary by Bernd-Christoph Kaemper on SOAF, followed by my response.SUMMARY: The thrust of Craig et al.'s critical review (which was proposed by the Publishing Research Consortium and conducted by the staff of three publishers) is that despite the fact that virtually all studies comparing the citation counts for OA and non-OA articles keep finding the OA citation counts to be higher, it has not been proved beyond a reasonable doubt that the relationship is causal.

I agree: It is merely highly probable, not proved beyond a reasonable doubt. And I also agree that not one of the studies done so far is without some methodological flaw that could be corrected. But it is also highly probable that the results of the methodologically flawless versions of all those studies will be much the same as the results of the current studies. That's what happens when you have a robust major effect, detected by virtually every study, and only ad hoc methodological cavils and special pleading to rebut each of them with. Here is a common sense overview:

(1) Research quality is a necessary, but not a sufficient condition for citation impact: The research must also be accessible to be cited.

(2) Research accessibility is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for citation impact: The research must also be of sufficient quality to be cited.

(3) The OA impact effect is the finding that an article's citation counts are positively correlated with the probability that that article has been made OA: The more an article's citations, the more likely that that article has been made OA.

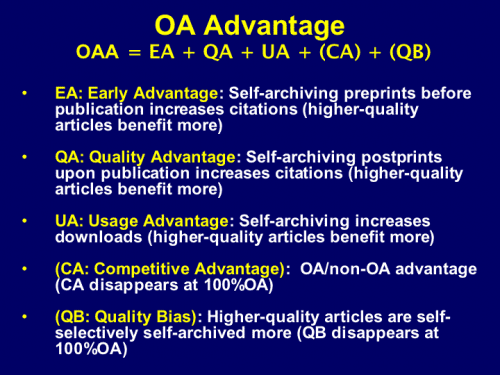

(4) That correlation has at least three (compatible) causal interpretations:

(4a) OA articles are more likely to be cited.

(4b) More-cited articles are more likely to be made OA.

(4c) A third factor makes it more likely that certain articles will be both more cited and made OA.

(5) Each of these causal interpretations is probably correct, and hence a contributor to the OA impact effect:

(5a) The better the article, the more likely it is to be cited, hence the more citations it gains if it is made more accessible (4a). (OA Article Quality Advantage, QA)

(5b) The better the article, the more likely it is to be made OA (4b). (OA Article Quality Bias, QB)

(5c) 10% of articles (and authors) receive 90% of citations. The authors of the better articles know they are better, and hence are more likely both to be cited and to make their articles OA, so as to maximize their visibility, accessibility and citations (4c). (OA Author QB and QA)

(6) In addition to QB and QA, there is an OA Early Access effect (EA): providing access earlier increases citations.

(7) The OA citation studies have not yet isolated and estimated the relative sizes of each of these (and other) contributing components. (OA also gives a Download Advantage (DA), and downloads are correlated with later citations; OA articles also have a Competitive Advantage (CA), but CA will vanish -- along with QB -- when all articles are OA).

(8) But the handwriting is on the wall as to the benefits of making articles OA, for those with eyes to see, and no conflicting interests to blind them.

Given all of this, here is a challenge for Craig et al: Instead of striving, like OJ Simpson's Dream Team, only to find flaws in the positive evidence for the OA impact differential, which is equally compatible with either interpretation (OA causes higher citations or higher citations cause OA) why don't Craig et al. do a simple study of their own? Since it is known that (in science) the top 10% of articles published receive 90% of the total citations made, why not test whether and to what extent the top 10% of articles published is over-represented among the c. 15% of articles that are being spontaneously made OA by their authors today? It is, after all, a logical possibility that all or most of the top 10% are already among the 15% that are being made OA: I think it's improbable; but it may repay Craig et al's effort to check whether it is so.

For if it did turn out that all or most of the top-cited 10% of articles are already among the c.15% of articles that are already being made OA, then reaching 100% OA would be far less urgent and important than I have been arguing, and OA mandates would likewise be less important. I for one would no longer find it important enough to archivangelize if I knew it was just for the bottom 90% of articles, the top 10% of articles having already been self-archived, spontaneously and sensibly, by their top 10% authors without having to be mandated. But it is Craig et al. who think this is closer to the truth, not me. So let them go out and demonstrate it.

Sally Morris (Publishing Research Consortium):Craig, Ian; Andrew Plume, Marie McVeigh, James Pringle & Mayur Amin (2007) Do Open Access Articles Have Greater Citation Impact? A critical review of the literature. Journal of Informetrics.A new, comprehensive review of recent bibliometric literature finds decreasing evidence for an effect of 'Open Access' on article citation rates. The review, now accepted for publication in the Journal of Informetrics, was proposed by the Publishing Research Consortium (PRC) and is available at its web site at www.publishingresearch.net. It traces the development of this issue from Steve Lawrence's original study in Nature in 2001 to the most recent work of Henk Moed and others.

Researchers have delved more deeply into such factors as 'selection bias' and 'early view' effects, and began to control more carefully for the effects of disciplinary differences and publication dates. As they have applied these more sophisticated techniques, the relationship between open access and citation, once thought to be almost self-evident, has almost disappeared.

Commenting on the paper, Lord May of Oxford, FRS, past president of the Royal Society, said 'In December 2005, the Royal Society called for an evidence-based approach to the scholarly communications debate. This excellent paper demonstrates that there is actually little evidence of a citation advantage for open access articles.'

The debate will certainly continue, and further studies will continue to refine current work. The PRC welcomes this discussion, and hopes that this latest paper may be a catalyst for a new round of informed scholarly exchange.

Sally Morris on behalf of the Publishing Research Consortium

It is notoriously tricky (at least since David Hume) to "prove" causality empirically. The thrust of the Craig et al. critique is that despite the fact that virtually all studies comparing the citation counts for OA and non-OA articles keep finding the OA citation counts to be higher, it has not been proven beyond a reasonable doubt that the relationship is causal.Bruce Royan wrote on diglib:

Sally claims that according to this article "the relationship between open access and citation, once thought to be almost self-evident, has almost disappeared."

Now I'm no Informetrician, but my reading of the article is that the authors reluctantly acknowledge that Open Access articles do have greater citation impact, but claim that this is less because they are Open Access per se, and more because:-they are available sooner than more conventionally published articles, orSally's point of view is understandable, since she is employed by a consortium of conventional publishers. It's interesting to note that the employers of the authors of this article are Wiley-Blackwell, Thomson Scientific, and Elsevier.

-they tend to be better articles, by more prestigious authors

Even more interesting is that, though this article has been accepted for publication in the conventional "Journal of Informetrics", a pdf of it (described as a summary, but there are 20 pages in JOI format, complete with diagrams, references etc) has already been mounted on the web for free download, in what might be mistaken for an example of green route open access.

Could this possibly be in order to improve the article's impact?

Professor Bruce Royan,

Concurrent Computing Limited.

I agree: It is merely highly probable, not proven beyond a reasonable doubt, that articles are more cited because they are OA, rather than OA merely because they are more cited (or both OA and more cited merely because of a third factor).

And I also agree that not one of the studies done so far is without some methodological flaw that could be corrected.

But it is also highly probable that the results of the methodologically flawless versions of all those studies will be much the same as the results of the current studies. That's what happens when you have a robust major effect, detected by virtually every study, and only ad hoc methodological cavils and special pleading to rebut each of them with.

But I am sure those methodological flaws will not be corrected by these authors, because -- OJ Simpson's "Dream Team" of Defense Attorneys comes to mind -- Craig et al's only interest is evidently in finding flaws and alternative explanations, not in finding out the truth -- if it goes against their client's interests...

Iain D.Craig: Wiley-BlackwellHere is a preview of my rebuttal. It is mostly just common sense, if one has no conflict of interest, hence no reason for special pleading and strained interpretations:

Andrew M.Plume, Mayur Amin: Elsevier

Marie E.McVeigh, James Pringle: Thomson Scientific

(1) Research quality is a necessary, but not a sufficient condition for citation impact: The research must also be accessible to be cited.

(2) Research accessibility is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for citation impact: The research must also be of sufficient quality to be cited.

(3) The OA impact effect is the finding that an article's citation counts are positively correlated with the probability that that article has been made OA: The more an article's citations, the more likely that that article has been made OA.

(4) This correlation has at least three causal interpretations that are not mutually exclusive:

(4a) OA articles are more likely to be cited.(5) Each of these causal interpretations is probably correct, and hence a contributor to the OA impact effect:

(4b) More-cited articles are more likely to be made OA.

(4c) A third factor makes it more likely that certain articles will be both more cited and made OA.

(5a) The better the article, the more likely it is to be cited, hence the more citations it gains if it is made more accessible (4a). (OA Article Quality Advantage, QA)(6) In addition to QB and QA, there is an OA Early Access effect (EA): providing access earlier increases citations.

(5b) The better the article, the more likely it is to be made OA (4b). (OA Article Quality Bias, QB)

(5c) 10% of articles (and authors) receive 90% of citations. The authors of the better articles know they are better, and hence are more likely both to be cited and to make their articles OA, so as to maximize their visibility, accessibility and citations (4c). (OA Author QB and QA)

(7) The OA citation studies have not yet isolated and estimated the relative sizes of each of these (and other) contributing components. (OA also gives a Download Advantage (DA), and downloads are correlated with later citations; OA articles also have a Competitive Advantage (CA), but CA will vanish -- along with QB -- when all articles are OA).

(8) But the handwriting is on the wall as to the benefits of making articles OA, for those with eyes to see, and no conflicting interests to blind them.

I do agree completely, however, with erstwhile (Princetonian and) Royal Society President Bob May's slightly belated call for "an evidence-based approach to the scholarly communications debate."

John Smith (JS) wrote in jisc-repositories:

I wonder if we can come at this discussion concerning the impact of OA on citation counts from another angle? Assuming we have a traditional academic article of interest to only a few specialists there is a simple upper bound to the number of citations it will have no matter how accessible it is.That is certainly true. It is also true that 10% of articles receive 90% of the citations. OA will not change that ratio, it will simply allow the usage and citations of those articles that were not used and cited because they could not be accessed to rise to what they would have been if they could have been used and cited.

JS: Also, the majority of specialist academics work in educational institutions where they have access to a wide range of paid for sources for their subject.OA is not for those articles and those users that already have paid access; it is for those that do not. No institution can afford paid access to all or most of the 2.5 million articles published yearly in the world's 24,000 peer-reviewed journals, and most institutions can only afford access to a small fraction of them.

OA is hence for that large fraction (the complement of the small fraction) of those articles that most users and most institutions cannot access. The 10% of that fraction that merit 90% of the citations today will benefit from OA the most, and in proportion to their merit. That increase in citations also corresponds to an increase in scholarly and scientific productivity and progress for everyone.

JS: Therefore any additional citations must mainly come from academics in smaller institutions that do not provide access to all relevant titles for their subject and/or institutions in the poorer countries of the world.It is correct that the additional citations will come from academics at the institutions that cannot afford paid access to the journals in which the cited articles appeared. It might be the case that the access denial is concentrated in the smaller institutions and the poorer countries, but no one knows to what extent that is true, and one can also ask whether it is relevant. For the OA problem is not just an access problem but an impact problem. And the research output of even the richest institutions is losing a large fraction of its potential research impact because it is inaccessible to the fraction to whom it is inaccessible, whether or not that missing fraction is mainly from the smaller, poorer institutions.

JS: Should it not be possible therefore to examine the citers to these OA articles where increased citation is claimed and show they include academics in smaller institutions or from poorer parts of the world?Yes, it is possible, and it would be a good idea to test the demography of access denial and OA impact gain. But, again, one wonders: Why would one assign this question of demographic detail a high priority at this time, when the access and impact loss have already been shown to be highly probable, when the remedy (mandated OA self-archiving) is at hand and already overdue, and when most of the skepticism about the details of the OA impact advantage comes from those who have a vested interest in delaying or deterring OA self-archiving mandates from being adopted?

(It is also true that a portion of the OA impact advantage is a competitive advantage that will disappear once all articles are OA. Again, one is inclined to reply: So what?)

This is not just an academic exercise but a call to action to remedy a remediable practical problem afflicting research and researchers.

JS: However, even if this were done and positive results found there is still another possible explanation. Items published in both paid for and free form are indexed in additional indexing services including free services like OAIster and CiteSeer. So it may be that it is not the availability per se that increases citation but the findability? Those who would have had access anyway have an improved chance of finding the article. Do we have proof that the additional citers accessed the OA version (assuming there is both an OA and paid for version)?Increased visibility and improved searching are always welcome, but that is not the OA problem. OAIster's usefulness is limited by the fact that it only contains the c. 15% of the literature that is being self-archived spontaneously (i.e., unmandated) today. Citeseer is a better niche search engine because computer scientists self-archive a much higher proportion of their research. But the obvious benchmark today is Google Scholar, which is increasingly covering all cited articles, whether OA or non-OA. It is in vain that Google Scholar enhances the visibility of non-OA articles for those would-be users to whom they are not accessible. Those users could already have accessed the metadata of those articles from online indices such as Web of Science or PubMed, only to reach a toll-access barrier when it came to accessing the inaccessible full-text corresponding to the visible metadata.

JS: It is possible that my queries above have already been answered. If so a reference to the work will suffice as a response.Accessibility is a necessary (but not a sufficient) condition for usage and impact. There is no risk that maximising accessibility will fail to maximise usage and impact. The only barrier between us and 100% OA is a few keystrokes.

I am a supporter of OA but also concerned that it is not falsely praised. If it is praised for some advantage and that advantage turns out not to be there it will weaken the position of OA proponents.

It is appalling that we continue to dither about this; it is analogous to dithering about putting on (or requiring) seat-belts until we have made sure that the beneficiaries are not just the small and the poor, and that seat-belts do not simply make drivers more safety-conscious.

JS: Even if the apparent citation advantage of OA turns out to be false it does not weaken the real advantages of OA. We should not be drawn into a time and effort wasting defence of it while there is other work to be done to promote OA.The real advantage of Open Access is Access. The advantage of Access is Usage and Impact (of which citations are one indicator). The Craig et al. study has not shown that the OA Impact Advantage is not real. It has simply pointed out that correlation does not entail causation. Duly noted. I agree that no time or effort should be spent now trying to demonstrate causation. The time and effort should be used to provide OA.

Bernd-Christoph Kaemper (B-CK) wrote on SOAF:I couldn't quite follow the logic of this posting. It seemed to be saying that, yes, there is evidence that OA increases impact, it is even trivially obvious, but, no, we cannot estimate how much, because there are possible confounding factors and the size of the increase varies.

Elsevier said that citation rates of their journals had gone up considerably because of the increased access through wide- spread online availability of their journals...

Online availability clearly increased the IF [journal citation impact factor]. In the FUTON subcategory, there was an IF gradient favoring journals with freely available articles. ..."

I think it is quite obvious why sources available with open access will be used and cited more often than others...

So the usefulness of open access is a matter of daily experience, not so much of academic discussions whether there is any empirical proof for a citation advantage of open access that may be isolated by eliminating all possible confounders...

That open access leads to more visibility and thereby potentially more citations is trivial, but this relative open access advantage will vary from journal to journal...

Due to the multitude of possible confounding factors I would not believe any of the figures calculated by Stevan Harnad as the cumulated lost impact, or conversely, the possible gain.

All studies have found that the size of the OA impact differential varies from field to field, journal to journal, and year to year. The range of variation is from +25% to over +250% percent. But the differential is always positive, and mostly quite sizeable. That is why I chose a conservative overall estimate of +50% for the potential gain in impact if it were not just the current 15% of research that was being made OA, but also the remaining 85%. (If you think 50% is not conservative enough, use the lower-bound 25%: You'll still find a substantial potential impact gain/loss. If you think self-selection accounts for half the gain, split it in half again: there's still plenty of gain, once you multiply by 85% of total citations.)

An interesting question that has since arisen (and could be answered by similar studies) is this:

It is a logical possibility that all or most of the top 10% are already among the 15% that are being made OA: I rather doubt it; but it would be worth checking whether it is so. [Attention lobbyists against OA mandates! Get out your scissors here and prepare to snip an out-of-context quote...]Since it is known that (in science) the top 10% of articles published receive 90% of the total citations made (Seglen 1992), to what extent is the top 10% of articles published over-represented among the c. 15% of articles that are being spontaneously made OA by their authors today?

[snip]The empirical studies of the relation between OA and impact have been mostly motivated by the objective of accelerating the growth of OA -- and thereby the growth of research usage and impact. Those who are oersuaded that the OA impact differential is merely or largely a non-causal self-selection bias are encouraged to demonstrate that that is the case.

If it did turn out that all or most of the top-cited 10% of articles are already among the c.15% of articles that are already being made OA, then reaching 100% OA would be far less urgent and important than I had argued, and OA mandates would likewise be less important. I for one would no longer find it important enough to archivangelize if I knew it was just for the bottom 90% of articles, the top 10% of articles having already been self-archived, spontaneously and sensibly, by their top 10% authors without having to be mandated.

[/snip]

Note very carefully, though, that the observed correlation between OA and citations takes the form of a correlation between the number of OA articles, relative to non-OA articles, at each citation level. The more highly cited an article, the more likely it is OA. This is true within journals, and within and across years, in every field tested.

And this correlation can arise because more-cited articles are more likely to be made OA or because articles that are made OA are more likely to be cited (or both -- which is what I think is in reality the case). It is certainly not the case that self-selection is the default or null hypothesis, and that those who interpret the effect as OA causing the citation increase hence have the burden of proof: The situation is completely symmetric numerically; so your choice between the two hypotheses is not based on the numbers, but on other considerations, such as prima facie plausibility -- or financial interest.

Until and unless it is shown empirically that today's OA 15% already contains all or most of the top-cited 10% (and hence 90% of what researchers cite), I think it is a much more plausible interpretation of the existing findings that OA is a cause of the increased usage and citations, rather than just a side-effect of them, and hence that there is usage and impact to be gained by providing and mandating OA. (I can quite understand why those who have a financial interest in its being otherwise [Craig et al. 2007] might prefer the other interpretation, but clearly prima facie plausibility cannot be their justification.)

I also think that 50% of total citations is a plausible overall estimate of the potential gain from OA, as long as it is understood clearly that that the 50% gain does not apply to every article made OA. Many articles are not found useful enough to cite no matter how accessible you make them. The 50% citation gain will mostly accrue to the top 10% of articles, as citations always do (though OA will no doubt also help to remedy some inequities and will sometimes help some neglected gems to be discovered and used more widely). In other words, the OA advantage to an article will be roughly proportional to that article's intrinsic citation value (independent of OA).

Other interesting questions: The top-cited articles are not evenly distributed among journals. The top journals tend to get the top-cited articles. It is also unlikely that journal subscriptions are evenly distributed among journals: The top journals are likely to be subscribed to more, and are hence more accessible.

So if someone is truly interested in these questions (as I am not!), they might calculate a "toll-accessibility index" (TAI) for each article, based on the number of researchers/institutions that have toll access to the journal in which that article is published. An analysis of covariance can then be done to see whether and how much the OA citation advantage is reduced if one controls for the article's TAI. (I suspect the answer will be: somewhat, but not much.)

B-CK: Could we do a thought experiment? From a representative group of authors, choose a sample of authors randomly and induce them to make their next article open access. Do you believe they will see as much gain in citations compared to their previous average citation levels as predicted from the various current "OA advantage" studies where several confounding factors are operating? Probably not - but what would remain of that advantage? -- I find that difficult to predict or model.From a random sample, I would expect an increase of around 50% or more in total citations, 90% of the increased citations going to the top 10%, as always.

B-CK: As I learned from your posting, you seem to predict that it will anyway depend on the previous citedness of the members of that group (if we take that as a proxy for the unknown actual intrinsic citation value of those articles), in the sense that more-cited authors will see a larger percentage increase effect.I don't think it's just a Matthew Effect; I think the highest quality papers get the most citations (90%), and the highest quality papers are apparently about 10% (in science, according to Seglen).

B-CK: To turn your argument around, most authors happily going open access in expectation of increased citation might be disappointed because the 50% increase will only apply to a small minority of them.That's true; but you could say the same for most authors going into research at all. There is no guarantee that they will produce the highest quality research, but I assume that researchers do what they do in the hope that they will, if not this time, then the next time, produce the highest quality research.

B-CK: That was the reason why I said that (as an individual author) I would rather not believe in any "promised" values for the possible gain.Where there is life, and effort, there is hope. I think every researcher should do research, and publish, and self-archive, with the ambition of doing the best quality work, and having it rewarded with valuable findings, which will be used and cited.

My "promise", by the way, was never that each individual author would get 50% more citations. (That would actually have been absurd, since over 50% of papers get no citations at all -- apart from self-citation -- and 50% of 0 is still 0.)

My promise, in calculating the impact gain/loss that you doubted, was to countries, research funders and institutions. On the assumption that the research output of each roughly covers the quality spectrum, they can expect their total citations to increase by 50% or more with OA, but that increase will be mostly at their high-quality end. (And the total increase is actually about 85% of 50%, as the baseline spontaneous self-archiving rate is about 15%.)

B-CK: That doesn't mean though that there are not enough other reasons to go for open access (I mentioned many of them in my posting).There are other reasons, but researchers' main motivation for conducting and publishing research is in order to make a contribution to knowledge that will be found useful by, and used by, and built upon by other researchers. There are pedagogic goals too, but I think they are secondary, and I certainly don't think they are strong enough to induce a researcher to make his publications OA, if the primary reason was not reason enough to induce them.

(Actually, I don't think any of the reasons are enough to induce enough researchers to provide OA, and that's why Green OA mandates are needed -- and being provided -- by researchers' institutions and funders.)

B-CK: With respect to the toll accessibility index, I completely agree. The occasional good article in an otherwise "obscure" journal probably has a lot to gain from open access, as many people would not bother to try to get hold of a copy should they find it among a lot of others in a bibliographic database search, if it doesn't look from the beginning like a "perfect match" of what they are looking for.You agree with the toll-accessibility argument prematurely: There are as yet no data on it, whereas there are plenty of data on the correlation between OA and impact.

B-CK: An interesting question to look at would also be the effect of open access on non-formal citation modes like web linking, especially social bookmarking. Clearly NPG is interested in Connotea also as a means to enhance the visibility of articles in their own toll access articles. Has anyone already tried such investigations?Although I cannot say how much it is due to other kinds of links or from citation links themselves, the University of Southampton, the first institution with a (departmental) Green OA self-archiving mandate, and also the one with the longest-standing mandate also has a surprisingly high webmetric, university-metric and G-factor rank:

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Bollen, J., Van de Sompel, H., Smith, J. and Luce, R. (2005) Toward alternative metrics of journal impact: A comparison of download and citation data. Information Processing and Management, 41(6): 1419-1440.

Brody, T., Harnad, S. and Carr, L. (2006) Earlier Web Usage Statistics as Predictors of Later Citation Impact. Journal of the American Association for Information Science and Technology (JASIST) 57(8) pp. 1060-1072.

Craig, Ian; Andrew Plume, Marie McVeigh, James Pringle & Mayur Amin (2007) Do Open Access Articles Have Greater Citation Impact? A critical review of the literature. Journal of Informetrics.

Davis, P. M. and Fromerth, M. J. (2007) Does the arXiv lead to higher citations and reduced publisher downloads for mathematics articles? Scientometrics 71: 203-215.

See critiques: 1 and 2.

Diamond, Jr. , A. M. (1986) What is a Citation Worth? Journal of Human Resources 21:200-15, 1986,

Eysenbach, G. (2006) Citation Advantage of Open Access Articles. PLoS Biology 4: 157.

Hajjem, C., Harnad, S. and Gingras, Y. (2005) Ten-Year Cross-Disciplinary Comparison of the Growth of Open Access and How it Increases Research Citation Impact. IEEE Data Engineering Bulletin 28(4) pp. 39-47.

Hajjem, C. and Harnad, S. (2006) Manual Evaluation of Robot Performance in Identifying Open Access Articles. Technical Report, Institut des sciences cognitives, Universite du Quebec a Montreal.

Hajjem, C. and Harnad, S. (2006) The Self-Archiving Impact Advantage: Quality Advantage or Quality Bias? Technical Report, ECS, University of Southampton.

Hajjem, C. and Harnad, S. (2007) Citation Advantage For OA Self-Archiving Is Independent of Journal Impact Factor, Article Age, and Number of Co-Authors. Technical Report, Electronics and Computer Science, University of Southampton.

Hajjem, C. and Harnad, S. (2007) The Open Access Citation Advantage: Quality Advantage Or Quality Bias? Technical Report, Electronics and Computer Science, University of Southampton.

Harnad, S. & Brody, T. (2004) Comparing the Impact of Open Access (OA) vs. Non-OA Articles in the Same Journals, D-Lib Magazine 10 (6) June

Harnad, S. (2005) Making the case for web-based self-archiving. Research Money 19(16).

Harnad, S. (2005) Maximising the Return on UK's Public Investment in Research. (Unpublished ms.)

Harnad, S. (2005) OA Impact Advantage = EA + (AA) + (QB) + QA + (CA) + UA. (Unpublished ms.)

Harnad, S. (2005) On Maximizing Journal Article Access, Usage and Impact. Haworth Press (occasional column).

Harnad, S. (2006) Within-Journal Demonstrations of the Open-Access Impact Advantage: PLoS, Pipe-Dreams and Peccadillos (LETTER). PLOS Biology 4(5).

Henneken, E. A., Kurtz, M. J., Eichhorn, G., Accomazzi, A., Grant, C., Thompson, D., and Murray, S. S. (2006) Effect of E-printing on Citation Rates in Astronomy and Physics. Journal of Electronic Publishing, Vol. 9, No. 2, Summer 2006

Henneken, E. A., Kurtz, M. J., Warner, S., Ginsparg, P., Eichhorn, G., Accomazzi, A., Grant, C. S., Thompson, D., Bohlen, E. and Murray, S. S. (2006) E-prints and Journal Articles in Astronomy: a Productive Co-existence Learned Publishing.

Kurtz, M. J., Eichhorn, G., Accomazzi, A., Grant, C. S., Demleitner, M., Murray, S. S. (2005) The Effect of Use and Access on Citations. Information Processing and Management, 41 (6): 1395-1402.

Kurtz, Michael and Brody, Tim (2006) The impact loss to authors and research. In, Jacobs, Neil (ed.) Open Access: Key strategic, technical and economic aspects. Oxford, UK, Chandos Publishing.

Lawrence, S, (2001) Online or Invisible?, Nature 411 (2001) (6837): 521.

Metcalfe, Travis S (2006) The Citation Impact of Digital Preprint Archives for Solar Physics Papers. Solar Physics 239: 549-553

Moed, H. F. (2006) The effect of 'Open Access' upon citation impact: An analysis of ArXiv's Condensed Matter Section (preprint)

Perneger, T. V. (2004) Relation between online 'hit counts' and subsequent citations: prospective study of research papers in the British Medical Journal. British Medical Journal 329:546-547.

Seglen, P.O. (1992) The skewness of science. The American Society for Information Science 43: 628-638

Saturday, March 17. 2007

Why Cornell's Institutional Repository Is Near-Empty

Critique of:SUMMARY: Cornell University's Institutional Repository (IR) so far houses only a very small percentage of its own annual research output, even though this output is the target content for Open Access (OA) IRs. As such, Cornell's IR is no different from all other IRs worldwide except those that have already adopted a "Green OA" deposit mandate. Alma Swan's international, multidisciplinary surveys have found that most researchers report they will not deposit without a mandate but will comply willingly if deposit is mandated by their institutions and/or their funders. Arthur Sale's comparative analyses of mandated and unmandated IRs have confirmed this in actual practise. Cornell's IR too has confirmed this with high deposit rates for the few subcollections that are mandated. IRs with Green OA mandates approach 100% OA within about 2 years. The worldwide baseline for unmandated self-archiving is about 15%.

Davis & Connolly's 2007 D-Lib article takes no cognizance of this prior published information. It surveys a sample of Cornell researchers for their attitudes to self-archiving and finds the usual series of uninformed misunderstandings, already long-catalogued and answered in published FAQs. The article then draws some incorrect conclusions derived entirely from incorrect assumptions it first makes, among them the following:

(1) The purpose of Green OA self-archiving is to compete with journals? (No, the purpose is to supplement subscription access by depositing the author's final draft online, free for all users who cannot access the subscription-based version.)The only thing Cornell needs to do if it wants its IR filled with Cornell's own research output is to mandate it.

(2) IRs should instead store the "grey literature"? (No, OA's target content is peer-reviewed research.)

(3) IRs are for preservation? (No, they are for research access-provision.)

(4) Some disciplines may not benefit from Green OA self-archiving? (The only disciplines that would not benefit would be those that do not benefit from maximizing the usage and impact of their peer-reviewed journal article output.)

Institutional Repositories: Evaluating the Reasons for Non-use of Cornell University's Installation of DSpace. Davis, P.M. & Connolly, M.J.L. D-Lib Magazine 13(3/4) March/April 2007On the contrary; little has been done to develop IRs apart from creating them; moreover, many surveys and analyses have evaluated faculty non-participation and identified how and why to remedy it: By mandating deposit. (See Sale and Swan references at the end of this posting.)

D & C: "Problem: While there has been considerable attention dedicated to the development and implementation of Institutional Repositories [IRs], there has been little done to evaluate them, especially with regards [sic] to faculty participation."

D & C: "Results: Cornell's DSpace is largely underpopulated and underused by its faculty."This is most decidedly true! The reason is that Cornell researchers are being given equivocal advice instead of an unequivocal mandate. (See: Cornell's Copyright Advice: Guide for the Perplexed Self-Archiver)

(I note that, unlike Harvard, Cornell is not one of the 132 Universities that have signed in support of the US Federal Green OA Mandate, the FRPAA; this may be a sign of equivocation, but in Cornell's defense, none of the 132 have yet practised what they petitioned (by adopting locally the global mandate they are urging federally). European, Australian and Asian Universities have been faster off the mark.

D & C: "[The only] steady growth [is in] collections in which [Cornell] university has made an administrative investment, such [as] requiring deposits of theses and dissertations into DSpace."This passage states the problem (empty IRs) as well as the solution (mandating deposit) -- but the article itself then proceeds to ignore this obvious and already known outcome, and instead goes on and on about the many groundless (and easily answered) reasons faculty cite for not depositing unless it is mandated.

The D & C article also wrongly imagines that the primary purpose of IRs is to preserve digital content, rather than to maximise research usage and access by supplementing paid journal access with free access to the author's final draft: (See: Against Conflating OA Self-Archiving With Preservation-Archiving )

D & C: "Cornell faculty have little knowledge of and little motivation to use DSpace."Correct. And in that respect Cornell faculty are exactly like faculty at all other universities worldwide that have IRs but no deposit mandate:

Swan, A. (2006) The culture of Open Access: researchers' views and responses, in Jacobs, N., Eds. Open Access: Key Strategic, Technical and Economic Aspects, chapter 7. Chandos.

D & C: "Many faculty use alternatives to institutional repositories, such as their personal Web pages and disciplinary repositories"If all or most faculty were indeed spontaneously despositing their peer-reviewed articles on their personal Web pages or in central disciplinary repositories (CRs) (like Arxiv), there would be no problem: 100% Open Access (OA) would already be upon us, for IRs could easily fill themselves by simply harvesting their faculty's output from their web-pages and CRs.

The trouble is that -- except where mandated -- most faculty are not depositing their articles on their Web pages today, and only a few sub-disciplines are depositing in CRs. Hence OA is only at about 15% today.

D & C: "[CRs] are perceived to have higher community salience than one's affiliate institution."Right now, the only two CRs with any appreciable content -- Arxiv and PubMed Central -- certainly do have "higher community salience" than IRs, since most IRs are mostly empty. But institutions need merely mandate depositing and the "salience" of their IRs will sail, along with the size of their contents.

(Moreover, the true success rate of a repository -- whether IR or CR -- is the percentage of its total annual target content that it is currently capturing. By that proportionate measure, central disciplinary CRs are in fact doing just as badly as unmandated IRs and the real champions are (unsurprisingly) the harvesters like Citeseer, OAIster and Google Scholar that trawl their contents from the distributed IRs and CRs.)

All IRs are OAI-compliant and interoperable. Researchers' institutions cover all of research output space. Hence researchers' own IRs are the natural and optimal locus for direct deposit. Institutions also have a proprietary interest in showcasing, monitoring, evaluating and storing their own research output -- as well as in maximizing its research impact. Hence both funders and institutions should mandate direct deposit in the researcher's own IR. (CRs can then harvest therefrom, if they wish.) (See: Optimizing OA Self-Archiving Mandates: What? Where? When? Why? How?)

D & C: "Faculty gave many reasons for not using repositories: redundancy with other modes of disseminating information"There is no "redundancy" with OA's target content: peer-reviewed journal articles. Those users who can afford paid access, have paid access. Those who do not, have no access. The purpose of OA self-archiving in IRs is to supplement the existing paid access, providing free access to the author's final draft, self-archived online, for those would-be users who do not have paid access to the journal's proprietary version.

(The authors of this article, D & C, as we shall see, draw precisely the conclusions from their article that they have themselves put into it, in the form of assumptions, often incorrect ones. Apart from that, all the do is amplify the volume of the faculty misunderstandings they sample, instead of correcting them.)

The purpose of maximizing research access is to maximise research impact (download, usage, applications, citations, productivity, progress).

D & C: "the learning curve [for depositing articles online]"A non-problem, cured by a few moments of instruction, plus a mandate:

Carr, L. and Harnad, S. (2005) Keystroke Economy: A Study of the Time and Effort Involved in Self-Archiving)

D & C: "confusion with copyright"A non-problem, already completely mooted by the Immediate-Deposit/Optional-Access Mandate: (See: Generic Rationale and Model for University Open Access Self-Archiving Mandate: Immediate-Deposit/Optional Access (ID/OA))

Only the depositing itself is mandated; setting access to the deposit as Open Access versus Closed Access is recommended but optional.

D & C: "fear of plagiarism"An old canard, cured by referring to Self-Archiving FAQ.

D & C: "having one's work scooped"Another old canard.

D & C: "associating one's work with inconsistent quality"Yet another old canard.

D & C: "concerns about whether posting a manuscript constitutes 'publishing'."One of the oldest canards of them all.

D & C: "Conclusion: While some librarians perceive a crisis in scholarly communication as a crisis in access to the literature, Cornell faculty perceive this essentially as a non-issue."Librarians' journal affordability problems helped draw attention to the research accessibility problem, but the affordability and accessibility problems are not the same, nor are their solutions.

Cornell faculty are right to regard the affordability problem as not their problem. The accessibility problem, however, is their problem, both from the point of view of Cornell researchers' own lost access to the work of researchers at other institutions (in journals that even Cornell cannot afford to subscribe to) and -- even more important (as most researchers at other institutions are not sitting as pretty as Cornell for subscriptions) -- from the point of view of Cornell researchers' lost research impact (owing to the access problems of would-be users at other institutions).

D & C: "Each discipline has a normative culture, largely defined by their reward system and traditions. If the goal of institutional repositories is to capture and preserve the scholarship of one's faculty, institutional repositories will need to address this cultural diversity."The target content of OA IRs is peer-reviewed journal articles. If there are any disciplines that do not care about maximising the usage and impact of their peer-reviewed journal article output, then there are indeed reasons to examine discipline differences. If not, then what is needed is not discipline-difference studies but pandisciplinary deposit mandates.

D & C: "most faculty host their digital objects on a personal website, where their long-term preservation is not secure. If institutions truly value the content created by their faculty, they must take some responsibility for the long-term curation of this content."OA IRs are for supplementary access-provision and usage-maximisation, not for preservation. (What needs preservation is the journal published version, not the author's OA draft.) (See: Against Conflating OA Self-Archiving With Preservation-Archiving)

But of course IRs can and will preserve their contents, to make sure their supplementary access provision perdures.

D & C: "There are two opposing philosophical camps among those who work to justify institutional repositories: one that views IRs as competition for traditional publishing, the other that sees IRs as a supplement to traditional publishing."There are indeed two opposing views of what IRs are for, but the opposition is certainly not about whether IRs compete with or supplement traditional publishing. It is about whether IRs are primarily for OA content (i.e., peer-reviewed research) or for other kinds of content (e.g., "grey literature"). (There is also some related confusion about whether IRs are primarily for supplementing access or for digital preservation.)

Among OA advocates there is no divergence whatsoever on the fact that OA IRs (Green OA) supplement journal publishing; they are not a substitute for it, nor a competitor to it.

(There is competition between subscription-based publishing and Gold OA publishing, but that is an entirely different matter, having nothing to do with IRs or Green OA.)

Here is a core example of how the authors of this article first make incorrect assumptions, and then simply proceed to derive their inevitably incorrect consequences:

D & C: "In 1994, Stevan Harnad wrote his Subversive Proposal for Electronic Publishing, in which he argued that all academics should make their research articles publicly available through open repositories. This collective effort would help to reduce the power wielded by publishers who have built economic barriers to limit scholars' access to the literature."(1) From the very outset, the Subversive Proposal was to supplement traditional publishing with (what we have since come to call) Green OA self-archiving of the author's peer-reviewed final draft. Self-archiving was never proposed as a substitute for peer-reviewed journal publication -- as a google search on "harnad supplement substitute" will repeatedly confirm!

Latent in the Subversive Proposal -- a Green OA supplement proposal -- was, of course, the possibility of an eventual transition to Gold OA publishing. But that is and always was treated as a hypothetical possibility, whereas Green OA self-archiving (which eventually led to the first OA IR software, EPrints, and eventually to the OA IR movement) was proposed as a concrete, practical action, within reach of all researchers -- a practical action that has since been widely tried, tested, and confirmed empirically to work, and to deliver the enhanced research usage and impact for which it was intended.

(2) Davis & Connolly have also completely conflated the explicitly stated purpose of the Subversive Proposal -- which was to maximize research access and usage -- with the library community's struggle with the journal affordability problem. Green OA self-archiving is not about "reducing publisher power" nor about changing economics. It is just about maximizing research access.

D & C: "In opposition, Clifford Lynch views IRs as supplements, not primary venues for scholarly publishing, and warns against assuming the role of certification in the scholarly publishing process."All OA IR advocates view IRs as supplements: a way to provide free access to the author's peer-reviewed final draft, accepted for publication by the "primary venue" (the journal) -- not as a substitute form of peer review or certification or publication.

D & C: "[Lynch] argues that "the institutional repository isn't a journal, or a collection of journals, and should not be managed like one""Preaching to the choir: No one thinks IRs are journals.

D & C: "Lynch fears that viewing IRs as instruments for undermining the economics of the current publishing system discounts their importance and reduces their ability to promote a broader spectrum of scholarly communication."IRs are not "instruments for undermining the economics of the current publishing system" they are instruments for maximizing the access and impact of currently published research articles.

D & C: "Institutional repositories may better serve to disseminate the so-called "grey literature": documents such as pamphlets, bulletins, visual conference presentations, and other materials that are typically ignored by traditional publishers."The idea that IRs should focus on the grey (unpublished) literature instead of the OA Green literature remains just as off-the-mark and wrong-headed today as on the day it was first mooted: (See: Cliff Lynch on Institutional Archives)

D & C: "DSpace was not conceived as competition to commercial publishers, but as a resource to capture, preserve and communicate the diversity of intellectual output of an institution's faculty and researchers It was designed specifically to deal with a wide range of content types including research articles, grey literature, theses, cultural materials, scientific datasets, institutional records, and educational materials, among others."More's the pity that DSpace does not now, nor did it ever, have its priorities straight. The #1 priority for IRs is and always has been (or ought to have been!) OA. (See: EPrints, DSpace or ESpace?)

D & C: "On May 1st, 2005, a policy was enacted that recommended, not required, that all researchers receiving grant monies from the National Institutes of Heath deposit final copies of their manuscripts in PubMed Central (PMC), a free digital archive of biomedical and life sciences journal literature. PMC offers many valuable services to authors, such as indexing in Medline (the primary literature index for the biomedical and life sciences), as well as dynamic links to the published version of their article. After eight months, the participation rate remained a dismal 3.8%. Lack of awareness of the policy was not cited as contributing to the low compliance rate. On December 14th, 2005, Senator Joseph Lieberman introduced the CURES Act (S.2104), which would require (not recommend) mandatory deposit of final manuscripts"The NIH Public Access Policy failed for three reasons (in order of priority):

The remedy for this was pointed out in advance to NIH (but went unheeded): "A Simple Way to Optimize the NIH Public Access Policy")(1) because it was not a mandate, but merely a request,

(2) because it allowed deposit to be delayed (up to a year) rather than immediate,

(3) and because it insisted upon central deposit, in PMC, instead of local deposit (in the fundee's own IR, harvestable by PMC).

The remedy -- the ID/OA mandate -- has since been taken on board in the European Research Advisory Board's policy recommendation.

ID/OA has just been adopted by University of Liege -- the first, let's hope, of many adopters, including the US's omnibus Federal Research Public Access Act (FRPAA). (See: How to Counter All Opposition to the FRPAA Self-Archiving Mandate)

D & C: "Cornell's DSpace is largely underpopulated and underused by its faculty. Its complex organization is seen at comparable institutions, but may discourage contributions to DSpace by making it appear empty. In addition, faculty have little knowledge of and no motivation to use DSpace."The only thing Cornell's DSpace is missing is the ID/OA mandate. That mandate needs to replace or at least complement Cornell's Copyright Advice: Guide for the Perplexed Self-Archiver.

D & C: "Each discipline has a normative culture, largely defined by their reward system and inertia. If the goal of institutional repositories is to capture and preserve the scholarship of one's faculty, IRs will need to address this cultural diversity."No, the remedy is not to delve into disciplinary diversity. It is to promote what all disciplines (indeed all of research) have in common, which is the need to maximize the usage and impact of their peer-reviewed research findings -- by mandating Green OA.

Stevan HarnadSwan, A. (2005) Open access self-archiving: An Introduction. JISC Technical Report.

Swan, Alma and Brown, Sheridan (2005) Open Access self-archiving. An author study. Published by JISC.

Swan, A., Needham, P., Probets, S., Muir, A., Oppenheim, C., O'Brien, A., Hardy, R., Rowland, F. and Brown, S. (2005) Developing a model for e-prints and open access journal content in UK further and higher education. Learned Publishing 18(1) pp. 25-40.

Swan, A. (2006) The culture of Open Access: researchers' views and responses, in Jacobs, N., Eds. Open Access: Key Strategic, Technical and Economic Aspects, chapter 7. Chandos Publishing (Oxford) Limited.

Sale, A. (2006) The Impact of Mandatory Policies on ETD Acquisition. D-Lib Magazine April 2006, 12(4).

Sale, A. (2006) Comparison of content policies for institutional repositories in Australia. First Monday, 11(4), April 2006.

Sale, A. (2006) The acquisition of open access research articles. First Monday, 11(9), October 2006.

Sale, A. (2007) The Patchwork Mandate D-Lib Magazine 13 1/2 January/February

Sale, Arthur (2006) Researchers and institutional repositories, in Jacobs, Neil, Eds. Open Access: Key Strategic, Technical and Economic Aspects, chapter 9, pages 87-100. Chandos Publishing (Oxford) Limited.

Harnad, S., Carr, L., Brody, T. & Oppenheim, C. (2003) Mandated online RAE CVs Linked to University Eprint Archives: Improving the UK Research Assessment Exercise whilst making it cheaper and easier. Ariadne 35 (April 2003).

Harnad, S. (2006) Opening Access by Overcoming Zeno's Paralysis, in Jacobs, N., Eds. Open Access: Key Strategic, Technical and Economic Aspects, chapter 8. Chandos Publishing (Oxford) Limited. .

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Sunday, January 21. 2007

The Open Access Citation Advantage: Quality Advantage Or Quality Bias?

Update Jan 1, 2010: See Gargouri, Y; C Hajjem, V Larivière, Y Gingras, L Carr,T Brody & S Harnad (2010) “Open Access, Whether Self-Selected or Mandated, Increases Citation Impact, Especially for Higher Quality Research”

Update Feb 8, 2010: See also "Open Access: Self-Selected, Mandated & Random; Answers & Questions"

This is a preview of some preliminary data (not yet refereed), collected by my doctoral student at UQaM, Chawki Hajjem. This study was done in part by way of response to Henk Moed's replies to my comments on Moed's (self-archived) preprint:

SUMMARY: Many studies have now reported the positive correlation between Open Access (OA) self-archiving and citation counts ("OA Advantage," OAA). But does this OAA occur because articles that are self-archived are more likely to be cited ("Quality Advantage": QA) or because articles that are more likely to be cited are more likely to be self-archived ("Quality Bias," QB)? The probable answer is both. Three studies [by Kurtz and co-workers in astrophysics, Moed in condensed matter physics, and Davis & Fromerth in mathematics] had attributed the OAA to QB [and to EA, the Early Advantage of self-archiving the preprint before publication] rather than QA. These three fields, however, happen to be among the minority of fields that (1) make heavy use of prepublication preprints and (2) have less of a postprint access problem than most other fields. Chawki Hajjem has now analyzed preliminary evidence based on over 100,000 articles from multiple fields, comparing self-selected self-archiving with mandated self-archiving to estimate the contributions of QB and QA to the OAA. Both factors contribute, and the contribution of QA is greater.

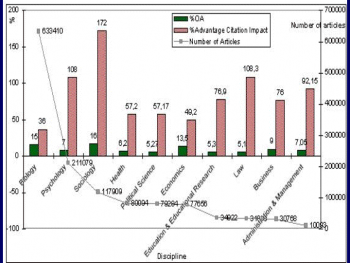

Moed, H. F. (2006) The effect of 'Open Access' upon citation impact: An analysis of ArXiv's Condensed Matter SectionMoed's study is about the "Open Access Advantage" (OAA) -- the higher citation counts of self-archived articles -- observable across disciplines as well as across years as in the following graphs from Hajjem et al. 2005 (red bars are the OAA):

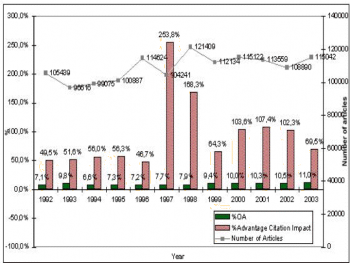

The focus of the present discussion is the factors underlying the OAA. There are at least five potential contributing factors, but only three of them are under consideration here: (1) Early Advantage (EA), (2) Quality Advantage (QA) and (3) Quality Bias (QB -- also called "Self-Selection Bias").FIGURE 1. Open Access Citation Advantage By Discipline and By Year.

Green bars are percentage of articles self-archived (%OA); red bars, percentage citation advantage (%OAA) for self-archived articles for 10 disciplines (upper chart) across 12 years (lower chart, 1992-2003). Gray curve indicates total articles by discipline and year.

Source: Hajjem, C., Harnad, S. and Gingras, Y. (2005) Ten-Year Cross-Disciplinary Comparison of the Growth of Open Access and How it Increases Research Citation Impact. IEEE Data Engineering Bulletin 28(4) pp. 39-47.

Preprints that are self-archived before publication have an Early Advantage (EA): they get read, used and cited earlier. This is uncontested.

Kurtz, Michael and Brody, Tim (2006) The impact loss to authors and research. In, Jacobs, Neil (ed.) Open Access: Key strategic, technical and economic aspects. Oxford, UK, Chandos Publishing.In addition, the proportion of articles self-archived at or after publication is higher in the higher "citation brackets": the more highly cited articles are also more likely to be the self-archived articles.

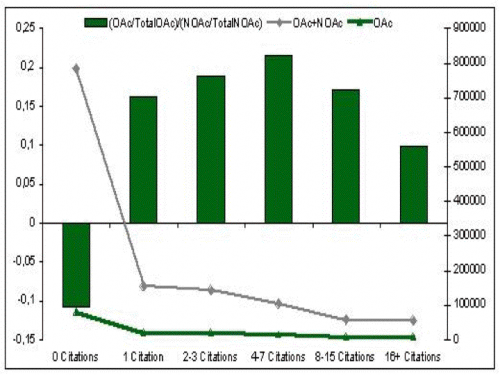

The question, then, is about causality: Are self-archived articles more likely to be cited because they are self-archived (QA)? Or are articles more likely to be self-archived because they are more likely to be cited (QB)?FIGURE 2. Correlation between Citedness and Ratio of Open Access (OA) to Non-Open Access (NOA) Ratios.

The (OAc/TotalOAc)/(NOAc/TotalNOAc) ratio (across all disciplines and years) increases as citation count (c) increases (r = .98, N=6, p<.005). The more cited an article, the more likely that it is OA. (Hajjem et al. 2005)

The most likely answer is that both factors, QA and QB, contribute to the OAA: the higher quality papers gain more from being made more accessible (QA: indeed the top 10% of articles tend to get 90% of the citations). But the higher quality papers are also more likely to be self-archived (QB).

As we will see, however, the evidence to date, because it has been based exclusively on self-selected (voluntary) self-archiving, is equally compatible with (i) an exclusive QA interpretation, (ii) an exclusive QB interpretation or (iii) the joint explanation that is probably the correct one.

The only way to estimate the independent contributions of QA and QB is to compare the OAA for self-selected (voluntary) self-archiving with the OAA for imposed (obligatory) self-archiving. We report some preliminary results for this comparison here, based on the (still small sample of) Institutional Repositories that already have self-archiving mandates (chiefly CERN, U. Southampton, QUT, U. Minho, and U. Tasmania).

FIGURE 3. Self-Selected Self-Archiving vs. Mandated Self-Archiving: Within-Journal Citation Ratios (for 2004, all fields).

S = citation counts for articles self-archived at institutions with (Sm) and without (Sn) a self-archiving mandate. N = citation counts for non-archived articles at institutions with (Nm) and without (Nn) mandate (i.e., Nm = articles not yet compliant with mandate). Grand average of (log) S/N ratios (106,203 articles; 279 journals) is the OA advantage (18%); this is about the same as for Sn/Nn (27972 articles, 48 journals, 18%) and Sn/N (17%); ratio is higher for Sm/N (34%), higher still for Sm/Nm (57%, 541 articles, 20 journals); and Sm/Sn = 27%, so self-selected self-archiving does not yield more citations than mandated; rather the reverse. (All six within-pair differences are significant: correlated sample t-tests.) (NB: preliminary, unrefereed results.)

Summary: These preliminary results suggest that both QA and QB contribute to OAA, and that the contribution of QA is greater than that of QB.

Discussion: On Fri, 8 Dec 2006, Henk Moed [HM] wrote:

HM: "Below follow some replies to your comments on my preprint 'The effect of 'Open Access' upon citation impact: An analysis of ArXiv's Condensed Matter Section'...The findings are definitely consistent for Astronomy and for Condensed Matter Physics. In both cases, most of the observed OAA came from the self-archiving of preprints before publication (EA).

"1. Early view effect. [EA] In my case study on 6 journals in the field of condensed matter physics, I concluded that the observed differences between the citation age distributions of deposited and non-deposited ArXiv papers can to a large extent - though not fully - be explained by the publication delay of about six months of non-deposited articles compared to papers deposited in ArXiv. This outcome provides evidence for an early view [EA] effect upon citation impact rates, and consequently upon ArXiv citation impact differentials (CID, my term) or Arxiv Advantage (AA, your term)."SH: "The basic question is this: Once the AA (Arxiv Advantage) has been adjusted for the "head-start" component of the EA (by comparing articles of equal age -- the age of Arxived articles being based on the date of deposit of the preprint rather than the date of publication of the postprint), how big is that adjusted AA, at each article age? For that is the AA without any head-start. Kurtz never thought the EA component was merely a head start, however, for the AA persists and keeps growing, and is present in cumulative citation counts for articles at every age since Arxiving began".HM: "Figure 2 in the interesting paper by Kurtz et al. (IPM, v. 41, p. 1395-1402, 2005) does indeed show an increase in the very short term average citation impact (my terminology; citations were counted during the first 5 months after publication date) of papers as a function of their publication date as from 1996. My interpretation of this figure is that it clearly shows that the principal component of the early view effect is the head-start: it reveals that the share of astronomy papers deposited in ArXiv (and other preprint servers) increased over time. More and more papers became available at the date of their submission to a journal, rather than on their formal publication date. I therefore conclude that their findings for astronomy are fully consistent with my outcomes for journals in the field of condensed matter physics."

Moreover, in Astronomy there is already 100% "OA" to all articles after publication, and this has been the case for years now (for the reasons Michael Kurtz and Peter Boyce have pointed out: all research-active astronomers have licensed access as well as free ADS access to all of the closed circle of core Astronomy journals: otherwise they simply cannot be research-active). This means that there is only room for EA in Astronomy's OAA. And that means that in Astronomy all the questions about QA vs QB (self-selection bias) apply only to the self-archiving of prepublication preprints, not to postpublication postprints, which are all effectively "OA."

To a lesser extent, something similar is true in Condensed-Matter Physics (CondMP): In general, research-active physicists have better access to their required journals via online licensing than other fields do (though one does wonder about the "non-research-active" physicists, and what they could/would do if they too had OA!). And CondMP too is a preprint self-archiving field, with most of the OAA differential again concentrated on the prepublication preprints (EA). Moreover, Moed's test for whether or not a paper was self-archived was based entirely on its presence/absence in ArXiv (as opposed to elsewhere on the Web, e.g., on the author's website or in the author's Institutional Repository).

Hence Astronomy and CondMP are fields that are "biassed" toward EA effects. It is not surprising, therefore, that the lion's share of the OAA turns out to be EA in these fields. It also means that the remaining variance available for testing QA vs. QB in these fields is much narrower than in fields that do not self-archive preprints only, or mostly.

Hence there is no disagreement (or surprise) about the fact that most of the OAA in Astronomy and CondMP is due to EA. (Less so in the slower-moving field of maths; see: "Early Citation Advantage?.")

I agree with all this: The probable quality of the article was estimated from the probable quality of the author, based on citations for non-OA articles. Now, although this correlation, too, goes both ways (are authors' non-OA articles more cited because their authors self-archive more or do they self-archive more because they are more cited?), I do agree that the correlation between self-archiving-counts and citation-counts for non-self-archived articles by the same author is more likely to be a QB effect. The question then, of course, is: What proportion of the OAA does this component account for?SH: "The fact that highly-cited articles (Kurtz) and articles by highly-cited authors (Moed) are more likely to be Arxived certainly does not settle the question of cause and effect: It is just as likely that better articles benefit more from Arxiving (QA) as that better authors/articles tend to Arxive/be-Arxived more (QB)."HM: "2. Quality bias. I am fully aware that in this research context one cannot assess whether authors publish [sic] their better papers in the ArXiv merely on the basis of comparing citation rates of archived and non-archived papers, and I mention this in my paper. Citation rates may be influenced both by the 'quality' of the papers and by the access modality (deposited versus non-deposited). This is why I estimated author prominence on the basis of the citation impact of their non-archived articles only. But even then I found evidence that prominent, influential authors (in the above sense) are overrepresented in papers deposited in ArXiv."