Wednesday, November 28. 2007

Administrative Keystroke Mandates To Record Research Output Can Serve As Open Access Mandates Too

There is no need to keep waiting for governmental OA mandates.Harnad, Stevan (2005) The OA Policy of Southampton University (ECS), UK: the "Keystroke" Strategy [Putting the Berlin Principle into Practice: the Southampton Keystroke Policy] . Delivered at Berlin 3 Open Access: Progress in Implementing the Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities, University of Southampton (UK).University OA mandates are natural extensions of universities' existing record-keeping, asset management, and performance-assessment policies. They complement research-funder OA mandates, and are the most efficient and productive way to monitor and credit compliance and fulfillment for both. Australia's Arthur Sale has done the most work on this. Please read what he has to say:

Arthur Sale

Arthur Sale The evidence is quite clear that advocacy does not work by itself, and never has worked anywhere. To repeat the bleeding obvious once again: depositing in repositories is avoidable work under a voluntary regime, and like all avoidable work it will be avoided by most academics, even if perceived to be in their best interests, and even if the work is minor. The work needs to be (a) required and (b) integrated into the work pattern of researchers, so it becomes the norm. This is the purpose of mandates - to make it clear to researchers that they are expected to do this work.

My research and published papers show that mandates do work, and they take a couple of years for the message to sink in. Enforcement need only be a light touch - reporting to heads of departments for example. [See references below.]

At the risk of boring some, may I point to a similar case in Australia. All universities are required to produce an annual return to the Australian Government of publications in the previous year in the categories of refereed journal articles, refereed conference papers, books, and book chapters. The universities make this known to their staff (a mandate), and they all fill out forms and provide photocopies of the works. The workload is considerably more than depositing a paper in a repository. The scheme has been going for many years and is regarded as part of the academic routine. The data is used by Government to determine part of the university block grant. The result is near 100% compliance.

What I am doing in Australia is pressing for this already existing mandate to be extended to the repositories. If the researcher deposits in the repository, and the annual return is automatically derived from the repository, then (a) the researcher wins because it takes him/her less time, (b) it takes the administrators less time as the process is automated and only needs to be audited, and (c) the repository delivers its usual benefits for those with eyes to see. All we need is for the research office to promulgate such a policy in each university. It is in their own interests as well as the university's.

Arthur Sale

University of Tasmania

Swan, A. and Brown, S. (2005) Open access self-archiving: An author study. JISC Technical Report, Key Perspectives Inc. http://eprints.ecs.soton.ac.uk/10999/

Sale, Arthur (2006) Researchers and institutional repositories, in Jacobs, Neil, Eds. Open Access: Key Strategic, Technical and Economic Aspects, chapter 9, pages 87-100. Chandos Publishing (Oxford) Limited. http://eprints.utas.edu.au/257/

Sale, A. The Impact of Mandatory Policies on ETD Acquisition. D-Lib Magazine April 2006, 12(4). http://dx.doi.org/10.1045/april2006-sale

Sale, A. Comparison of content policies for institutional repositories in Australia. First Monday, 11(4), April 2006. http://firstmonday.org/issues/issue11_4/sale/index.html

Sale, A. The acquisition of open access research articles. First Monday, 11(9), October 2006. http://www.firstmonday.org/issues/issue11_10/sale/index.html

Sale, A. (2007) The Patchwork Mandate D-Lib Magazine 13 1/2 January/February http://www.dlib.org/dlib/january07/sale/01sale.html

Saturday, November 24. 2007

Victory for Labour, Research Metrics and Open Access Repositories in Australia

Posted by Arthur Sale in the American Scientist Open Access Forum:

Posted by Arthur Sale in the American Scientist Open Access Forum:Yesterday, Australia held a Federal Election. The Australian Labor Party (the previous opposition) have clearly won, with Kevin Rudd becoming the Prime-Minister-elect.

What has this to do with the American Scientist Open Access Forum? Well the policy of the ALP is that the plans for the Research Quality Framework (the RQF - our research assessment exercise) will be immediately scrapped, and it will be replaced by a cheaper and metrics-based assessment, presumably a year or two later.

At first sight this is a setback for open access in Australia, because institutional repositories are not essential for a metrics-based research assessment. They just help improve the metrics. However, the situation may be turned to advantage, and there are several major pluses.(1) Previous RQF grants should have ensured that every university in Australia now has a repository. Just mostly empty, or mostly dark, or both.It should now be crystal clear to every university in Australia that citations and other measures will be key in the future. It should be equally clear that they should do everything possible to increase their performance on these measures. Any university that fails to immediately implement an ID/OA mandate (Immediate Deposit, Open Access when possible) in its institutional repository is simply deciding to opt out of research competition, or mistakenly thinks that it knows better. Although I suppose there is still the weak excuse that it is all too hard to understand or think about.

(2) The advisers in the Department of Education, Science & Technology (DEST) haven’t changed. The Accessibility Framework (ie open access) is still in place as a goal.

(3) A new metric-based evaluation could and should be steered to be a multi-metric based one. The ALP has already stated that it will be discipline-dependent.

(4) If the Rudd government is serious about efficiency in higher education, they could simply instruct DEST to require universities to put all their currently reported publications in a repository (ID/OA policy), from which the annual reports would be automatically derived. In addition all the desired publication metrics would also be derived, at any time. The Accessibility Framework would be achieved.

Here is the edited text of a press release by the shadow minister before the election. The boldface over some paragraphs is mine.

Arthur Sale

Professor of Computer Science

University of Tasmania[BEGINS]

Senator Kim Carr

Labor Senator for Victoria

Shadow Minister for Industry, Innovation, Science and Research

Thursday, 15 November 2007 (58/07)

Building a strong future for Australian research

Federal Labor’s key research initiatives, announced during yesterday’s Campaign Launch, highlight our commitment to a research revolution.

[snip]

A Rudd Labor Government will be committed to rebuilding the national innovation system and, over time, doubling the amount invested in R&D in Australia.

· Labor will bring responsibility for innovation, industry, science and research into a single Commonwealth Department.

· Labor will develop a set of national innovation priorities to sit over the national research priorities. Together, these will provide a framework for a national innovation system, ensuring that the objectives of research programs and other innovation initiatives are complementary.

· Labor will abolish the Howard Government’s flawed Research Quality Framework, and replace it with a new, streamlined, transparent, internationally verifiable system of research quality assessment, based on quality measures appropriate to each discipline. These measures will be developed in close consultation with the research community. Labor will also address the inadequacies in current and proposed models of research citation. Labor’s model will recognise the contribution of Australian researchers to Australia and the world.

[snip]

· Labor recognises the importance of basic research in the creation of new knowledge, and also the value and breadth of Australian research effort across the humanities, creative arts and social sciences as well as scientific and technological disciplines.

The Howard Government has allocated $87 million for the implementation of the RQF. Labor will seek to redirect the residual funds to encourage genuine industry collaboration in research.

[snip]

Thursday, November 22. 2007

UK Research Evaluation Framework: Validate Metrics Against Panel Rankings

Once one sees the whole report, it turns out that the HEFCE/RAE Research Evaluation Framework is far better, far more flexible, and far more comprehensive than is reflected in either the press release or the Executive Summary.

SUMMARY: Three things need to be remedied in the UK's proposed HEFCE/RAE Research Evaluation Framework:

(1) Ensure as broad, rich, diverse and forward-looking a battery of candidate metrics as possible -- especially online metrics -- in all disciplines.

(2) Make sure to cross-validate them against the panel rankings in the last parallel panel/metric RAE in 2008, discipline by discipline. The initialized weights can then be fine-tuned and optimized by peer panels in ensuing years.

(3) Stress that it is important -- indeed imperative -- that all University Institutional Repositories (IRs) now get serious about systematically archiving all their research output assets (especially publications) so they can be counted and assessed (as well as accessed!), along with their IR metrics (downloads, links, growth/decay rates, harvested citation counts, etc.).

If these three things are systematically done -- (1) comprehensive metrics, (2) cross-validation and calibration of weightings, and (3) a systematic distributed IR database from which to harvest them -- continuous scientometric assessment of research will be well on its way worldwide, making research progress and impact more measurable and creditable, while at the same time accelerating and enhancing it.

It appears that there is indeed the intention to use many more metrics than the three named in the executive summary (citations, funding, students), that the metrics will be weighted field by field, and that there is considerable open-mindedness about further metrics and about corrections and fine-tuning with time. Even for the humanities and social sciences, where "light touch" panel review will be retained for the time being, metrics too will be tried and tested.

This is all very good, and an excellent example for other nations, such as Australia (also considering national research assessment with its Research Quality Framework), the US (not very advanced yet, but no doubt listening) and the rest of Europe (also listening, and planning measures of its own, such as EurOpenScholar).

There is still one prominent omission, however, and it is a crucial one:

The UK is conducting one last parallel metrics/panel RAE in 2008. That is the last and best chance to test and validate the candidate metrics -- as rich and diverse a battery of them as possible -- against the panel rankings. In all other fields of metrics -- biometrics, psychometrics, even weather forecasting metrics – before deployment the metric predictors first need to be tested and shown to be valid, which means showing that they do indeed predict what they were intended to predict. That means they must correlate with a "criterion" metric that has already been validated, or that has "face-validity" of some kind.

The RAE has been using the panel rankings for two decades now (at a great cost in wasted time and effort to the entire UK research community -- time and effort that could instead have been used to conduct the research that the RAE was evaluating: this is what the metric RAE is primarily intended to remedy).

But if the panel rankings have been unquestioningly relied upon for 2 decades already, then they are a natural criterion against which the new battery of metrics can be validated, initializing the weights of each metric within a joint battery, as a function of what percentage of the variation in the panel rankings each metric can predict.

This is called "multiple regression" analysis: N "predictors" are jointly correlated with one (or more) "criterion" (in this case the panel rankings, but other validated or face-valid criteria could also be added, if there were any). The result is a set of "beta" weights on each of the metrics, reflecting their individual predictive power, in predicting the criterion (panel rankings). The weights will of course differ from discipline by discipline.

Now these beta weights can be taken as an initialization of the metric battery. With time, "super-light" panel oversight can be used to fine-tune and optimize those weightings (and new metrics can always be added too), to correct errors and anomalies and make them reflect the values of each discipline.

(The weights can also be systematically varied to use the metrics to re-rank in terms of different blends of criteria that might be relevant for different decisions: RAE top-sliced funding is one sort of decision, but one might sometimes want to rank in terms of contributions to education, to industry, to internationality, to interdisciplinarity. Metrics can be calibrated continuously and can generate different "views" depending on what is being evaluated. But, unlike the much abused "university league table," which ranks on one metric at a time (and often a subjective opinion-based rather than an objectiveone), the RAE metrics could generate different views simply by changing the weights on some selected metrics, while retaining the other metrics as the baseline context and frame of reference.)

To accomplish all that, however, the metric battery needs to be rich and diverse, and the weight of each metric in the battery has to be initialised in a joint multiple regression on the panel rankings. It is very much to be hoped that HEFCE will commission this all-important validation exercise on the invaluable and unprecedented database they will have with the unique, one-time parallel panel/ranking RAE in 2008.

That is the main point. There are also some less central points:

The report says -- a priori -- that REF will not consider journal impact factors (average citations per journal), nor author impact (average citations per author): only average citations per paper, per department. This is a mistake. In a metric battery, these other metrics can be included, to test whether they make any independent contribution to the predictivity of the battery. The same applies to author publication counts, number of publishing years, number of co-authors -- even to impact before the evaluation period. (Possibly included vs. non-included staff research output could be treated in a similar way, with number and proportion of staff included also being metrics.)

The large battery of jointly validated and weighted metrics will make it possible to correct the potential bias from relying too heavily on prior funding, even if it is highly correlated with the panel rankings, in order to avoid a self-fulfilling prophecy which would simply collapse the Dual RAE/RCUK funding system into just a multiplier on prior RCUK funding.

Self-citations should not be simply excluded: they should be included independently in the metric battery, for validation. So should measures of the size of the citation circle (endogamy) and degree of interdisciplinarity.

Nor should the metric battery omit the newest and some of the most important metrics of all, the online, web-based ones: downloads of papers, links, growth rates, decay rates, hub/authority scores. All of these will be provided by the UK's growing network of UK Institutional Repositories. These will be the record-keepers -- for both the papers and their usage metrics -- and the access-providers, thereby maximizing their usage metrics.

REF should put much, much more emphasis on ensuring that the UK network of Institutional Repositories systematically and comprehensively records its research output and its metric performance indicators.

But overall, thumbs up for a promising initiative that is likely to serve as a useful model for the rest of the research world in the online era.

References

Harnad, S., Carr, L., Brody, T. & Oppenheim, C. (2003) Mandated online RAE CVs Linked to University Eprint Archives: Improving the UK Research Assessment Exercise whilst making it cheaper and easier. Ariadne 35.

Brody, T., Kampa, S., Harnad, S., Carr, L. and Hitchcock, S. (2003) Digitometric Services for Open Archives Environments. Proceedings of European Conference on Digital Libraries 2003, pp. 207-220, Trondheim, Norway.

Harnad, S. (2006) Online, Continuous, Metrics-Based Research Assessment. Technical Report, ECS, University of Southampton.

Harnad, S. (2007) Open Access Scientometrics and the UK Research Assessment Exercise. Proceedings of 11th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Scientometrics and Informetrics 11(1), pp. 27-33, Madrid, Spain. Torres-Salinas, D. and Moed, H. F., Eds.

Brody, T., Carr, L., Harnad, S. and Swan, A. (2007) Time to Convert to Metrics. Research Fortnight pp. 17-18.

Brody, T., Carr, L., Gingras, Y., Hajjem, C., Harnad, S. and Swan, A. (2007) Incentivizing the Open Access Research Web: Publication-Archiving, Data-Archiving and Scientometrics. CTWatch Quarterly 3(3).

See also: Prior Open Access Archivangelism postings on RAE and metrics

Stevan Harnad

The following had been based on the earlier press alone, before seeing the full report. The press release had said:"For the science-based disciplines, a new bibliometric indicator of research quality is proposed, based on the extent to which research papers are cited by other publications. This new indicator will be combined with research income and research student data, to drive the allocation of HEFCE research funding in these disciplines"Comments:

"For the arts, humanities and social sciences (where quantitative approaches are less developed) we will develop a light touch form of peer review, though we are not consulting on this aspect at this stage."

(1) Citations, prior funding and student counts are fine, as candidate metrics. (Citations, suitably processed and contextually weighted, are a strong candidate, but it is important not to give prior funding too high a weight, or else it collapses the UK's Dual RAE/RCUK funding system into just a multiplier effect on prior RCUK funding.

(2) But where are the rest of the candidate metrics? article counts, book counts, years publishing, co-author counts, co-citations, download counts, link counts, download/citation growth rates, decay rates, hub/authority index, endogamy index... There is such a rich and diverse set of candidate metrics. It is completely arbitrary, and unnecessary, to restrict consideration to just an a-priori three.

(3) And how and against what are the metrics to be validated? The obvious first choice is the RAE panel rankings themselves: RAE has been relying on them unquestioningly for two decades now, and the 2008 RAE will be a (last) parallel panel/metric exercise.

(4) The weights on a rich, diverse battery of metrics should be jointly validated (using multiple regression analysis) against the panel rankings to initialize the weight of each metric, and then the weights should be calibrated and adjusted field by field, with the help of peer panels.

(5) It is not at all obvious that the humanities and social sciences do not have valid, predictive metrics too: They too write and read and use and cite articles and books, receive research funding, train postgraduate students, etc.

The metric RAE should be open-minded, open-ended forward-looking, in the digital online era, putting as many candidates as possible into the metric equation, testing the outcome against panel rankings, and then calibrating them, continuously, field by field, so as to optimise them. This is not the time to commit, a priori, to just 3 metrics, not yet validated and weighted, in science fields, nor to stick to panel review in other fields, again because of a priori assumptions about its metrics.

Let 1000 metric flowers bloom, initialize their weights against the parallel panel rankings (and any other validated or face-valid criteria) and then set to work optimising those initial weights, assessing continuously, field by field, across time. The metrics should be stored and harvestable from each institution's Open Access Institutional Repository, along with the research publications and data on which they are based.

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Wednesday, November 21. 2007

Creative Mix-and-Match Re-Use Is Not What Open Access Is About

In Newsweek, Brian Braiker discusses some interesting and important copyright, licensing and re-use issues -- about books re-using wikipedia material without attribution, about blogs posting published journal figures, about the re-use of free-culture text, photographs and music -- but it is important to understand that these are not Open Access (OA) issues.

In Newsweek, Brian Braiker discusses some interesting and important copyright, licensing and re-use issues -- about books re-using wikipedia material without attribution, about blogs posting published journal figures, about the re-use of free-culture text, photographs and music -- but it is important to understand that these are not Open Access (OA) issues. OA primarily concerns the very special case of research articles published in peer-reviewed journals (about 2.5 million articles a year, in about 25,000 journals). All those articles, without exception, are (and always have been) author give-aways, written exclusively for maximal research usage and impact, not for royalty revenue. OA means making them freely accessible online to all would-be users webwide (for reading, downloading, storing, printing-off, data-crunching, using the findings in further research, building upon them, citing them -- but not necessarily for verbatim re-publication or re-posting of the text or figures -- beyond quoting limited verbatim text excerpts, with attribution, under "Fair Use": more than that still requires the author's permission).

OA does not require adopting a special CC attribution/re-use license (although if desired by the author and accepted by the publisher, such a license is always welcome). Nor does OA require the kinds of blanket mix-and-match re-use rights that teenagers might like to have for making and posting their own creative re-mixes out of commercial music or movies. That is a problem, but not an OA problem.

It is not even clear whether a blanket right to mix-and-match scientific content (even with attribution) would be a good thing. (Figures need not be re-posted, for example; the OA version can be linked; HTML even allows pinpoint linking to the specific figure rather than to the document as a whole.)

What sets OA's primary target apart is that it is an exception-free give-away corpus, wanting only to be read and used (but not necessarily re-published). It should not be conflated with or constrained by the needs of the much larger and more complicated and exception-ridden body of creative digital work of which it is merely a small, special subset.

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Sunday, November 18. 2007

Open Access in the Last Millennium

I thought that as the American Scientist Open Access Forum approaches its 10th year, readers might find it amusing (and perhaps enlightening) to see where the discourse stood 20 years ago. That was before the Web, before online journals, and before Open Access -- yet many of the same issues were already being debated.

I thought that as the American Scientist Open Access Forum approaches its 10th year, readers might find it amusing (and perhaps enlightening) to see where the discourse stood 20 years ago. That was before the Web, before online journals, and before Open Access -- yet many of the same issues were already being debated.Alhough I might have traced it back still further, to BBS Open Peer Commentary, 30 years ago, and although my first substantive posting was September 27 1986, for me it feels as if it all began with a jolt on November 19 1986, on sci.lang, with "Saumya,...you have shit-for-brains" -- which led to "Skywriting" (c. 1987, unpublished, unposted), which turned into "Scholarly Skywriting" (1990), Psycoloquy (1991), "PostGutenberg Galaxy" (1991), CogPrints (1997), the Self-Archiving FAQ (as of 1997), the AmSci Forum (1998), the critique of the e-biomed proposal (1999), EPrints (2000), mandates and metrics (2001), and then the BOAI (2002).

See how much of it is already lurking in this 1990 posting on COMMED:

Date: Tues, Mar 13 1990 4:12 am

From: har...@Princeton.EDU (Stevan Harnad)

To: loeb@geocub

Subject: Re: Journals

Cc: PA...@phoenix.cambridge.ac.uk, jour_...@nyuacf.BITNET

ON THE SCHOLARLY AND EDUCATIONAL POTENTIAL OF MULTIPLE EMAIL NETWORKS

[From: COMMED]Stevan Harnad

Princeton University

Gerald M. Phillips, Professor, Speech Communication, Pennsylvania State

University (G...@PSUVM.BITNET) wrote on Commed against the idea of

"on-line journals." His critique contains enough of the oft-repeated

(and I think erroneous) criticisms of the new medium that I think it's

worth a point by point rebuttal. I write as the editor, for over a

decade now, of a refereed international journal published by Cambridge

University Press (in the conventional paper/print medium), but also as

an impassioned advocate of multiple-email networks and their (I think)

revolutionary potential. I am also the new moderator of PSYCOLOQUY,

an email list devoted to scholarly electronic discussion in psychology

and related disciplines. Professor Phillips wrote:

> There is [1] an explicit hostility to print media on computer networks.

> There is a crisis in the publishing industry because of [2] technological

> innovations, [3] TV, and second hand booksellers, and among book reviewers

> there is consternation because [4] the number of journals proliferates and

> the quality of the texts declines. I am responding to the proposal to

> establish an electronic journal, and I am responding negatively.

Not one of these points speaks against electronic journals; rather,

they are points in their favor: (1) The hostility to print is justified,

inasmuch as it wastes time and resources and confers no advantage (which

cannot be duplicated by resorting to hard copy when needed anyway).

(2) Technological innovations such as photo-copying are problems for

the print media -- unsolved and probably unsolvable -- but not for the

virtual media, whose economics will be established pre-emptively along

more realistic lines, given the new technology. The passive CRTs in (3)

TV may be competing with the written word, but the interactive CRTs in

the electronic media are in a position to fight back. (4) Word glut and

quality decline are problems with the message (and how we control its

quality -- a real problem, in which I am very interested), not with the

medium. This leaves nothing of this first list of objections. Let's go on:

> The book, magazine, or journal is still the most convenient learning

> center known to civilization. It is portable, requires no power supply, is

> easily stored, and one can write comments on the pages without resorting

> to hypertext.

These arguments would have been just as apt if applied to Gutenberg

on behalf of the illuminated manuscript, or against writing itself, in

favor of the oral tradition. Other than habit, they have no logical or

practical support at all. And the clincher is that the situation is not

"either/or." To the extent that people are addicted to their marginal

doodling (or to electricity-free yurts), hard copy will always be

available as a supplement.

> Furthermore, the contemplation that enters composition of the

> typical article is important. Hasty publication results in error and sometimes

> danger. I urge examination of the editorial policies of NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL

> OF MEDICINE or DAEDALUS as examples of the best editorial policies. It is

> crucial in publishing to have careful editing and responsible writing.

There is one logical error and one non sequitur here: (i) Making it

POSSIBLE for people to communicate faster and on a more global scale

does not imply that they are no longer allowed to wait and reflect as

long as they wish! (ii) Ceterum censeo: Quality control is a

medium-independent problem; I have plenty of ideas about how to

implement peer review in this medium even more effectively than in the

print media.

> I do not wish to indict users of electronic media, but I have encountered

> a fair share of irresponsible people who write out of passion or worse --

> cuteness.

The problem here is a demographic one, having to do with the anarchic

initial conditions in which the new medium was developed. "Flaming"

was what the first electronic discussion was called, and it began as

spontaneous combustion among the creators of the medium (computer hackers,

for the most part) and students (who have a lot of idle time on their

hands). The form of trivial pursuit that ensued is no more representative

of the intrinsic possibilities of this medium than it would have been

if we had left it up to Gutenberg and a legion of linotype operators

to decide for us all what should appear on the printed page. Again, the

problem is with implementation and quality control, not the medium itself.

> I realize how important some exchanges are and I will argue

> with data and without passion for the efficacy of applying CMC to some

> aspects of classroom operation. Computerized cardfiles and other databases

> are essential to good scholarship. Networks like AMANET and similar

> medical operations provide important information conveniently. What

> characterizes a totally responsible network, however, is the willingness

> to spend money to make it work. Accumulating a database and monitoring its

> contents is crucial for uses of a network must have confidence in what they read.

These applications are all commendable, but supremely unimaginative.

The real revolutionary potential of electronic network communication is

in scholarship rather than education. I am convinced that the medium

is better matched to the pace and scope and interactiveness of human

mentation than any of its predecessors. In fact, it is as much of a

milestone as the advent of writing, and finally returns the potential pace

of the interaction -- which writing and print slowed down radically --

to the tempo of the natural speech from which so much of our cognitive

capacity arose.

> A great many scholars (mostly untenured) rail at the policies of contempo-

> rary scholarly journals, and often they are "on target." Journals sometimes

> use an "old boy" network to exclude new and vital ideas. Journals are often

> ponderously slow and it is difficult for many people to take editorial

> criticism. On the other hand, journals protect us from egregious error and

> and libel and the copyright laws protect us from plagiarism.

But the egregious error here is to fail to realize that electronic

networks can exercise peer review just as rigorously (or unrigorously)

as any other medium. And just as there are hierarchies of print

journals (ranked with respect to how rigorously they are refereed),

this can be done here too, including levels at which manuscripts or

ideas are circulated to one's peers for pre-referee scrutiny, as in

symposia and conferences, or even informal discussion. The possibilities

are enormous; objections like the above ones (and they are not unique

to Professor Phillips) serve only to demonstrate how the entrenched old

medium and its habits can blind us to promising alternatives.

> Plagiarism is a major concern in using an electronic network. I am

> hesitant to share material that might be useful because my copyrights are

> not protected on this network. I enjoy the chitchat effect, but I have

> told several people who have contacted me about my "on-line" course, that

> I would be happy to share articles or have them come out an observe. I

> would not attempt to offer advice using this medium. It would be

> guaranteed to be half-baked and inapposite.

I have two replies here; one objective and quite decisive, the other

a somewhat subjective observation: There are ways to implement peer

discussion that will preserve priority as safely as the ordinary

mail, telephone and word-processor media (none completely immune to

techno-vandalism these days, by the way) to which we already entrust

our prepublication ideas and findings. I'll discuss these in the future.

As food for thought, consider that it would be simple to implement a

network with read/write access only for a group of peers in a given

specialty, where every posting is seen by everyone who matters in the

specialty (and is archived for the record, to boot). These are the people

who ASSIGN the priorities. A wider circle might have read-only access,

and perhaps one of them might try (and even succeed) to purloin an

idea and publish it as his own -- either in a low-level print journal

or a low-level electronic group. So what? The peers saw it first, and

know whence it came, and where and when, with the archive to confirm it

(printed out in hard copy, if you insist!). That's the INTRINSIC purpose

of scholarly priority. If some enterprising vita-stuffer up for promotion

at New Age College pries the covers off my book and substitutes his own,

that's not a strike against the printed medium, is it?

Now the subjective point: It seems paradoxical, to say the least, to be

worried about word glut and quality decline at the same time as being

preoccupied with priority and plagiarism. Here is some more food for

thought: The few big ideas that there are will not fail to be attributed

to their true source as a result of the net. As to the many little ones

(the "minimal publishable units," or what have you), well, I suppose

that a scholar can spend his time trying to protect those too -- or he

can be less niggardly with them in the hope that something bigger might

be spawned by the interaction.

It's all a matter of scale. I'm inclined to think that for the really

creative thinker, ideas are not in short supply. It's the tree that

bears the fruit that matters: "He who steals my apples, steals trash,"

or something like that. The rival anecdote is that Einstein was asked

in the fifties by some tiresome journalist -- a harbinger of our

self-help/new-age era -- what activity he was usually engaged in when

he got his creative ideas (shaving? showering? walking? sleeping?), and

he replied that he really couldn't say, because he had only had one or

two creative ideas in his entire lifetime... (Nor was he particularly

secretive about them, I might add, engaging in intense scholarly

correspondence about them with his peers, most of whom could not even

grasp, much less pass them off as their own.)

> While serving on a promotion and tenure committee, I opposed consideration

> of materials "published" on-line in examining the credentials of candidates.

> That is an antediluvian view, I know, but in the sciences especially,

> accuracy and responsibility is critical and to date, only the referee

> process give us any assurance at all.

Too bad. Promotion/tenure review is a form of peer review too, and is

not such an oracular machine as to afford to ignore potentially

informative data. I, for one, might even consider looking at

unpublished (hence, a fortiori, unrefereed) manuscripts if there

appeared to be grounds for doing so, in order to make a more informed

decision. But never mind; if the direction I am advocating prevails,

peer review, such as it is, will soon be alive and well on the

electronic networks, and contributions will be certifiably CV-worthy.

> Interchanges like this are useful. We get a chance to exchange views with

> people we do not know and often we find some intriguing possibilities in

> these notes and messages. But I still do not know who I am communicating

> with and I have no confirmation of their data. I can use caveat emptor on

> their ideas, but I cannot give them professional credit for them, nor can

> I claim any for my own.In short, here is your extreme argument AGAINST

> electronic journals.

There is, I am told, a complexity-theoretic bottom-line in networking

called the "authentication problem." I can in principle post a libelous,

plagiaristic message in your name without being detected; hence it will be

difficult to formulate enforceable laws to regulate the net. In practice,

this need not be a problem, however, so look on the bright side. I

really am the one indicated on my login. And even if I weren't, it hardly

matters for THIS discussion (as opposed to the future peer-reviewed ones

mentioned earlier). All that matters is my message, which can stand on

its own merits as a counterargument FOR electronic journals.

Stevan Harnad

Gerald M. Phillips

> Two points you did not attack were (1) the problem of protection of

> copyrights and (2) the convenience of books. Note, please that read

> only does not protect anyone so long as personal computers have print

> screen keys.

Currently, copyright is protected if you copyright a hard copy of what

you have written. Anyone is free to do this prior to every screenful,

but it sure would slow "skywriting" down to the old terrestrial pace.

In practice, however, we don't bother to copyright until we're much

further downstream: Our scholarly correspondence, our conference papers

and our preliminary drafts circulated for "comment without quotation"

do not enjoy copyright, so why be more protective of electronic

drafts? Because they're easier to abscond with? But, as I wrote earlier,

if the primary read/write network to which it is posted consists of

all the peers of the realm, and they see it first, and it's archived

when they see it, what is there to fear? What better way to establish

priority? Isn't it their eyes that matter?

Books are much more a habit than a convenience. I'm sure that if you

gave me an itemized list of their virtues I could match them (and then

some) with the merits of electronic text. (E.g., books are portable,

but they have to be physically duplicated and lugged; in principle,

everything written could be available everywhere there's a plug or

antenna, to anyone, anytime... etc.)

> Furthermore, the overwhelming number of faculties do not

> participate in networks. It is somewhat like the problem people are

> having with VCRs. Most people can learn how to play movies. Few bother

> to learn how to record from broadcasts. Most PC users really have

> expensive typewriters. I know -- it is their own fault. And it is

> probably different in the sciences, but it seems to me that designing

> access to knowledge for a minority will only widen the ignorance gap.

Computers and networks have become so friendly that everyone is just a

2-minute demo away from sufficient facility for full access. The barrier

is so tiny that it's absurd to think that it can hold people back,

particularly once the revolutionary potential of scholarly skywriting is

demonstrated and a quorum of the peers of each realm become addicted. The

"virtual" environment can mimic what we're used to as closely as necessary

to mediate a total transition. In fact, nothing has a better chance

to NARROW the ignorance gap than the global, interactive and virtually

instantaneous airwaves of the friendly skies.

> I'd be interested in your proposals about ensuring quality. I am not so sure

> of your proposals re: read only, but I'd be happy to look at them. I am not

> a Luddite. I believe I have the largest enrollment class learning entirely

> via computer-mediated communication. And it is a performance class (group

> problem solving). It is both popular and effective, but the computer has

> been adapted to the needs of the class not the reverse. I think that

> putting journals on-line (at least at the moment) is a case of "we have the

> machinery, why not use it?"

The idea is to have a vertical (peer expertise) and a horizontal

(temporal-archival) dimension of quality control. The vertical dimension

would be a hierarchy of expertise, with read/write access for an

accredited group of peers at a given level and read-only access at the

level immediately below it, but with the right to post to a peer at

the next higher level, who can in turn post your contribution for you,

if he judges that it to is good enough. (A record of valuable mediated

postings could result in being voted up a level.) A single editor, or an

editorial board, are simply a special case of this very same mechanism,

where one person or only a few mediate all writing privileges.

That's the vertical hierarchy, based on degrees of expertise,

specialization, and record of contributions in a given field. In

principle, this hierarchy can trickle down all the way to general access

for nonspecialists and students at the lowest read/write level (the

equivalent of "flaming," and, unfortunately, the only level that exists

among the "unmoderated" groups on the net currently, while in today's

so-called "moderated" groups all contributions are filtered through one

person, usually one with no special qualifications or answerability).

So far, even among the elite, this would still be just brainstorming,

at the pilot stage of inquiry. The horizontal dimension would then take

the surviving products of all this skywriting, referee them the usual

way (by having them read, criticized and revised under peer scrutiny)

and then archiving them (electronically) according to the level of rigor

of the refereeing system they have gone through (corresponding, more or

less, to the current "prestige hierarchy" and level of specialization

among print journals). Again, an unrefereed "vanity press" could be the

bottom of the horizontal hierarchy.

> And please address the issue of those of us who make our living out of the

> printed word and fear plagiarism above earthquakes and forest fires.

> Gerald M. Phillips, Pennsylvania State University

I imagine that a different system of values and expectations will be

engendered by the net. One may have to make one's reputation increasingly

by being a fertile collaborator rather than a prolific monad. I think

interactive productivity ("interproductivity") will turn out to be

just as viable, answerable and rewardable a way of establishing one's

intellectual territory as the old way; it's just that the territory will

be much less exclusive, more overlapping and interdependent. That's the

cumulative direction in which inquiry has been heading all along anyway.

As to words themselves: I think it will be possible to protect them

just as well as in the old media. The ones who are really able to use

the language (like the ones who have really new ideas or findings) will

still be a tiny minority, as they are now and always will be, and we'll

know even better who they are and what they have written. It'll be easier

to steal a few of their screenfuls for lowly use, but, as always, it will

be impossible to steal their source. As to the rest -- marginal ideas and

marginal prose -- I can't really work up a sense of urgency about them;

it seems to me, however, that it will be just as easy as before to make

sure they get their dubious due, in terms of their official standing in

the two-dimensional hierarchy.

Stevan Harnad

Harnad, S. (1990) Scholarly Skywriting and the Prepublication Continuum of Scientific Inquiry Psychological Science 1: 342 - 343 (reprinted in Current Contents 45: 9-13, November 11 1991).Stevan Harnad

Harnad, S. (1991) Post-Gutenberg Galaxy: The Fourth Revolution in the Means of Production of Knowledge. Public-Access Computer Systems Review 2 (1): 39 - 53 (also reprinted in PACS Annual Review Volume 2 1992; and in R. D. Mason (ed.) Computer Conferencing: The Last Word. Beach Holme Publishers, 1992; and in: M. Strangelove & D. Kovacs: Directory of Electronic Journals, Newsletters, and Academic Discussion Lists (A. Okerson, ed), 2nd edition. Washington, DC, Association of Research Libraries, Office of Scientific & Academic Publishing, 1992); and in Hungarian translation in REPLIKA 1994; and in Japanese in Research and Development of Scholarly Information Dissemination Systems 1994-1995.

Harnad, S. (1995) Universal FTP Archives for Esoteric Science and Scholarship: A Subversive Proposal. In: Ann Okerson & James O'Donnell (Eds.) Scholarly Journals at the Crossroads; A Subversive Proposal for Electronic Publishing. Washington, DC., Association of Research Libraries, June 1995.

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Friday, November 16. 2007

OA As "Research Spam": II

On Thu, 15 Nov 2007, Joseph Esposito wrote:

On Thu, 15 Nov 2007, Joseph Esposito wrote: "Hey, Stevan, come off it. Read the article. Once again you pick a fight when I mostly agree with you."I was commenting on your interview rather than your article, but if you insist, here goes. The comments are much the same. I think we are galaxies apart, Joe, because you keep on imagining that OA is about unrefereed peer-to-peer content, whereas it is about making all peer-reviewed journal articles freely accessible online:

Comments on: Esposito, J. (2007) Open Access 2.0: The nautilus: where - and how - OA will actually work. The Scientist 21(11) 52.

open access does not appear to increase dissemination significantly... [because] Most researchers are affiliated with institutions, whether academic, governmental, or corporate, that have access to most of the distinguished literature in the field.Strongly disagree. You think there is little or no access problem; user surveys and library budget statistics suggest otherwise.

Thus, though there may be some exceptional situations, especially in the short term, the increased dissemination brought about by open access takes place largely at the margins of the research community.Strongly disagree. On the contrary, it is the top 10-20% of articles -- the ones most users use and cite -- that benefit most from being made OA. (They receive 80-90% of the citations.)

Another important reason open access does not significantly increase dissemination is that attention, not scholarly content, is the scarce commodity. You can build it, but they may not come.Strongly disagree. To repeat, OA is about published journal articles; so making them free online merely adds to whatever access they enjoy already.

It is one thing to write an article and upload it to a Web server somewhere, where it will be indexed by Google and its ilk. It is fully another thing for someone to find that article out of the growing millions on the Internet by happening upon just the right combination of keywords to type into a search bar.Strongly disagree, and this is the heart of the equivocation. You are speaking here about self-publishing of unrefereed, unpublished papers, whereas OA is about making published, peer-reviewed articles OA -- whether by publishing them in an OA journal or by self-archiving them in an OA Institutional Repository (IR).

The very same indices and search engines that find the published articles will find the OA ones too, because making them OA is just an add-on to publishing them in the first place. It is only because you keep seeing the OA papers as not being peer-reviewed and published, Joe, that you give yourself and others the impression that there is an either/or here -- when in reality OA is about both/and.

Would you rather double the amount of published information available to you, or increase the amount of time you have to review information you can already access by one hour a day? We are awash in information, but short on time to evaluate it. Open access only worsens this by opening the floodgates to more and more unfiltered information.This is a false opposition: OA is about accessing all journal articles, not just the minority that your institution can afford. If there are too many articles and too little time, affordability is surely not the way to cope with it! Let it all be OA and then decide how much of it you can afford the time to read. The candidates are all available via exactly the same indexes and search engines. The only difference is that without OA, many are inaccessible, whereas with OA they all are.

open access is most meaningful within a small community whose members know each other and formally and informally exchange the terms of discourse.You are again thinking of direct, peer-to-peer exchange of unrefereed content, whereas OA is about peer-reviewed, published journal articles, irrespective of community size. (The usership of most published research journal articles is very small.)

Many of the trappings of formal publishing are of little interest to many tight-knit communities of researchers. Who needs peer review, copy editing, or sales and marketing?I agree about not needing the sales and marketing, and perhaps the copy editing too; but since OA is about peer-reviewed journal articles, the answer to that is: all users need it.

what of the work for which there is little or no audience? What if there is simply no market? This is the ideal province of open access publishing: providing services to authors whose work is so highly specialized as to make it impossible to command the attention of a wide readership.Most journal articles have little or no audience. This is a spurious opposition. And we are talking about OA, not necessarily OA publishing.

the innermost spiral of the shell of a nautilus, where a particular researcher wishes to communicate with a handful of intimates and researchers working in precisely the same area. Many of the trappings of formal publishing are of little interest to this group. Peer review? But these are the peers; they can make their own judgments.The peers are quite capable of making the distinction between one another's unrefereed preprints and their peer-reviewed journal articles; and the difference is essential, regardless of the size of the field. OA is not about dispensing with peer review. It is about maximizing access to its outcome.

the next spiral is for people in the field but not working exactly on the topic of interest to the author; one more spiral and we have the broader discipline (e.g., biochemistry); beyond that are adjacent disciplines (e.g., organic chemistry); until we move to scientists in general, other highly educated individuals, university administrators, government policy-makers, investors, and ultimately to the outer spirals, where we have consumer media, whose task is to inform the general public.I can't follow all of this: It seems to me all these "spirals" need peer-reviewed content. There is definitely a continuum from unrefereed preprints to peer-reviewed postprints -- I've called that the "Scholarly Skywriting" continuum -- but peer-review continues to be an essential function in ensuring the quality of the outcome, and certifying it as worth the time to read and the effort of trying to build upon or apply.

Harnad, S. (1990) Scholarly Skywriting and the Prepublication Continuum of Scientific Inquiry. Psychological Science 1: 342 - 343 (reprinted in Current Contents 45: 9-13, November 11 1991).

not all brands are created equal.That's what journal names, peer-review standards and track records are for

Whatever the virtues of traditional publishing, authors may choose to work in an open-access environment for any number of reasons. For one, they simply may want to share information with fellow researchers, and posting an article on the Internet is a relatively easy way to do thatAgain the false opposition: It is not "traditional publishing" vs. an unrefereed free-for-all. OA is about making traditionally peer-reviewed and published articles free for all online.

(I think some of the funding agencies have been misinformed about the benefits of open access, and they certainly have been misinformed about the costs, especially over the long term, but it certainly is within the prerogatives of a funding agency to stipulate open-access publishing.)The funding agencies are mandating OA, not OA publishing. They have been correctly informed about the benefits of OA (it maximizes research access, usage and impact); the costs of IRs and Green OA self-archiving are negligible and the costs of Gold OA publishing are irrelevant (since OA publishing is not what is being mandated).

Whether in the long term mandated Green OA will lead to a transition to Gold OA is a matter of speculation: No one knows whether or when. But if and when it does, the institutional money currently paying for non-OA subscriptions will be more than enough to pay for Gold OA publishing (which will amount to peer review alone) several times over.

open access would be useful for: an article that may have been rejected by one or more publishers, but the author still wants to get the material "out there";No, OA is not for "research spam" (as you called it, more candidly, in your Interview): OA is for all peer-reviewed research; all 2.5 million articles published in all 25,000 peer-reviewed research journals, in all disciplines, countries and languages, at all levels of the journal quality hierarchy.

an author who may be frustrated by the process and scheduling of traditional publishers;Authors can certainly self-archive their preprints early if they wish,

but OA begins with the refereed postprint (and that can be self-archived on the day the final draft is accepted).

an author who may have philosophical reservations about working with large organizations, especially those in the for-profit sector, not to mention deep and growing suspicions about the whole concept of intellectual property.I am not sure what all that means, but it's certainly not researchers' primary motivation for providing OA, nor its primary benefit.

A reason to publish in an open-access format need not be very strong, as the barriers to such publication are indeed low. It takes little: an Internet connection, a Web server somewhere, and an address for others to find the material.Again, the equivocation: There is no "OA format." The target content is published, peer-reviewed journal articles, and OA means making them accessible free for all online. Peer-to-peer exchange of unrefereed papers is useful, but that is not what OA is about, or for.

Over time the list of invited readers may grow, and some names may be dropped from the list. The author, in other words, controls access to the document. This access can be extended to an academic department or to the members of a professional society; access can be granted to any authenticated directory of users.This is all just about the exchange of unrefereed content. It is not about OA.

At some point the author may remove all access restrictions, making the document fully open access.Making unrefereed content freely accessible online is useful, but it is not what OA is about.

It is a matter of debate as to whether any of these steps, including the final one, constitutes "publication," but it is indisputable that access can be augmented and that the marginal cost of doing so approaches zero. Providing free online access to unrefereed, unpublished content is not what OA is about, or for.

The fundamental tension in scholarly communications today is between the innermost spiral of the nautilus, where peers, narrowly defined, communicate directly with peers, and the outer spirals, which have been historically well-served by traditional means. Open-access advocates sit at the center and attempt to take their model beyond the peers.There is no tension at all. Unrefereed preprints, circulated for peer feedback, are and have always been an earlier embryological stage of the publication continuum, with peer-review and publication the later stage. OA does not sit at the center. It is very explicitly focused on the published postprint, though self-archiving the preprint is always welcome too.

Now, Joe, can we agree that we do indeed disagree?

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Thursday, November 15. 2007

Publishing Management Consultant: "Open Access Is Research Spam"

Joseph Esposito is an independent management consultant (the "portable CEO") with a long history in publishing, specializing in "interim management and strategy work at the intersection of content and digital technology."

SUMMARY: Joseph Esposito, a management consultant, says Open Access (OA) is "research spam." But OA's explicit target content is all 2.5 million peer-reviewed articles published annually in the world's 25,000 peer-reviewed research journals. (So either all research is spam or OA is not spam after all!).

Esposito says researchers' problem isn't access to journal articles (they already have that): rather, it's not having the time to read them. This will come as news to the countless researchers worldwide who are denied access daily to the articles in the journals their institution cannot afford, and to the authors of those articles, who are losing all that potential research impact.

Search engines find it all, tantalizingly, but access depends on being able to afford the subscription tolls. Esposito also says OA is just for a small circle of peers: How big does he imagine the actual usership of most journal articles is?

Esposito applauds the American Chemical Society (ACS) executives' bonuses for publishing profit, even though ACS is supposed to be a Learned Society devoted to maximizing research access, usage and progress, not a commercial company devoted to deriving profit from restricting research access only to those who can afford to pay them for it (and for their bonuses).

Esposito describes the efforts of researchers to inform their institutions and funders of the benefits of mandating OA as lobbying, but he does not attach a name to what anti-OA publishers are doing when they hire expensive pit-bull consultants to spread disinformation about OA in an effort to prevent OA self-archiving from being mandated. (Another surcharge for researchers, in addition to paying for their bonuses?)

Esposito finds it tautological that surveys report that authors would comply with OA mandates, but he omits to mention that over 80% of those researchers report that they would self-archive willingly if mandated. (And where does Esposito think publishers would be without existing publish-or-perish mandates?)

Esposito is right, though, that OA is a matter of time -- but not reading time, as he suggests. The only thing standing between the research community and 100% OA to all of its peer-reviewed research article output is the time it takes to do the few keystrokes per article it takes to provide OA. That is what the mandates (and the metrics that reward them) are meant to accomplish at long last.

In an interview by The Scientist (a follow-up to his article, "The nautilus: where - and how - OA will actually work"), Esposito says Open Access (OA) is "research spam" -- making unrefereed or low quality research available to researchers whose real problem is not insufficient access but insufficient time.

In arguing for his "model," which he calls the "nautilus model," Esposito manages to fall (not for the first time) into many of the longstanding fallacies that have been painstakingly exposed and corrected for years in the self-archiving FAQ. (See especially Peer Review, Sitting Pretty, and Info-Glut.)

Like so many others, with and without conflicting interests, Esposito does the double conflation (1) of OA publishing (Gold OA) with OA self-archiving (of non-OA journal articles) (Green OA), and (2) of peer-reviewed postprints of published articles with unpublished preprints. It would be very difficult to call OA research "spam" if Esposito were to state, veridically, that Green OA self-archiving means making all articles published in all peer-reviewed journals (whether Gold or not) OA. (Hence either all research is spam or OA is not spam after all!).

Instead, Esposito implies that OA is only or mainly for unrefereed or low quality research, which is simply false: OA's explicit target is the peer-reviewed, published postprints of all the 2.5 million articles published annually in all the planet's 25,000 peer-reviewed journals, from the very best to the very worst, without exception. (The self-archiving of pre-refereeing preprints is merely an optional supplement, a bonus; it is not what OA is about, or for.)

Esposito says researchers' problem is not access to journal articles: They already have that via their institution's journal subscriptions; their real problem is not having the time to read those articles, and not having the search engines that pick out the best ones.

Tell that to the countless researchers worldwide who are denied access daily to the specific articles they need in the journals to which their institution cannot afford to subscribe. (No institution comes anywhere near being able to subscribe to all 25,000, and many are closer to 250.)

And tell it also to the authors of all those articles to which all those would-be users are being denied access; their articles are being denied all that research impact. Ask users and authors alike whether they are happy with affordability being the "filter" determining what can and cannot be accessed. Search engines find it all for them, tantalizingly, but whether they can access it depends on whether their institutions can afford a subscription.

Esposito says OA is just for a small circle of peers ("6? 60? 600? but not 6000"): How big does he imagine the actual usership of most of the individual 2.5 million annual journal articles to be? Peer-reviewed research is an esoteric, peer-to-peer process, for the contents of all 25,000 journals: research is conducted and published, not for royalty income, but so that it can be used, applied and built upon by all interested peer specialists and practitioners, to the benefit of the tax-payers who fund their research; the size of the specialties varies, but none are big, because research itself is not big (compared to trade, and trade publication).

Esposito applauds the American Chemical Society (ACS) executives' bonuses for publishing profit, oblivious to the fact that the ACS is supposed to be a Learned Society devoted to maximizing research access, usage and progress, not a commercial company devoted to deriving profit from restricting research access only to those who can afford to pay them for it.

Esposito also refers (perhaps correctly) to researchers' amateurish efforts to inform their institutions and funders of the benefits of mandating OA as lobbying -- passing in silence over the fact that the real lobbying pro's are the wealthy anti-OA publishers who hire expensive pit-bull consultants to spread disinformation about OA in an effort to prevent Green OA from being mandated.

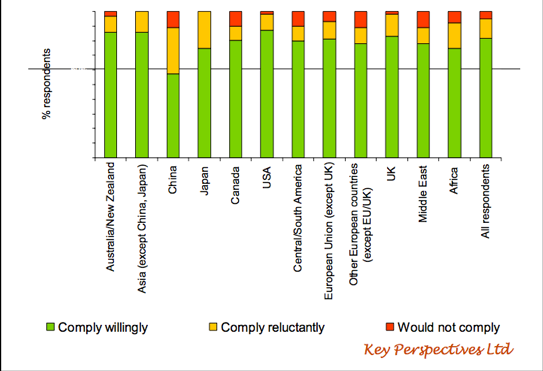

Esposito finds it tautological that surveys report that authors would comply with OA mandates ("it's not news that people would comply with a requirement"), but he omits to mention that most researchers surveyed recognised the benefits of OA, and over 80% reported they would self-archive willingly if it was mandated, only 15% stating they would do so unwillingly. (One wonders whether Esposito also finds the existing and virtually universal publish-or-perish mandates of research institutions and funders tautological -- and where he thinks the publishers for whom he consults would be without those mandates.)

Esposito is right, though, that OA is a matter of time -- but not reading time, as he suggests. The only thing standing between the research community and 100% OA to all of its peer-reviewed research output is the time it takes to do a few keystrokes per article. That, and only that, is what the mandates are all about, for busy, overloaded researchers: Giving those few keystrokes the priority they deserve, so they can at last start reaping the benefits -- in terms of research access and impact -- that they desire. The outcome is optimal and inevitable for the research community; it is only because this was not immediately obvious that the outcome has been so long overdue.

But the delay has been in no small part also because of the conflicting interests of the journal publishing industry for which Esposito consults. So it is perhaps not surprising that he should perceive it otherwise, unperturbed if things continue at a (nautilus) snail's pace for as long as possible...

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Wednesday, November 14. 2007

Who Downgraded the WHO OA Mandate -- And Why?

Why was the WHO IGWG OA recommendation downgraded from "requiring" OA to just "strongly encouraging" it? As Manon Ress and Peter Suber point out, this is simply a replay of the failed NIH policy, likewise downgraded from a requirement, tried for 2 years, resoundingly unsuccessful, and now being upgraded again to a requirement by the US Congress (only to be vetoed by George Bush). As repeatedly shown by Alma Swan's surveys of what authors say they will do and Arthur Sale's studies of what authors actually do, only a requirement (mandate) works.

Why was the WHO IGWG OA recommendation downgraded from "requiring" OA to just "strongly encouraging" it? As Manon Ress and Peter Suber point out, this is simply a replay of the failed NIH policy, likewise downgraded from a requirement, tried for 2 years, resoundingly unsuccessful, and now being upgraded again to a requirement by the US Congress (only to be vetoed by George Bush). As repeatedly shown by Alma Swan's surveys of what authors say they will do and Arthur Sale's studies of what authors actually do, only a requirement (mandate) works. The following prior wording:

(b) promote public access to the results of government funded research, through requirements that all investigators funded by governments submit to an open access database an electronic version of their final, peer-reviewed manuscripts.has for some reason been changed in the November Geneva version to:

(b) promote public access to the results of government funded research, by strongly encouraging that all investigators funded by governments submit to an open access database an electronic version of their final, peer-reviewed manuscripts.George Santayana (on being condemned to repeat history) comes to mind.

Candour prompts the following shame-faced disclosure: In the very first mandate recommendation of them all, this feckless archivangelist also cravenly allowed himself to be persuaded once -- but only once! -- to equivocate on mandating vs. "strongly encouraging," despite having insisted on the need to mandate self-archiving from the outset. To mortify me, compare the original wording of the 2003 recommendation first submitted to the UK Parliamentary Select Committee with the subsequent (downgraded) version. Fortunately, only one mention of "mandate" was diluted to "strong encouragement." The rest of the mentions are all the m-word, and it was that, fortunately, that the wise members of the Select Committee hewed to in their actual recommendation...

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

No Need To Keep Waiting For Gold OA

On Tue, 13 Nov 2007, Michael Smith [MS] (Anthropology, ASU, wrote in the American Scientist Open Access Forum):

On Tue, 13 Nov 2007, Michael Smith [MS] (Anthropology, ASU, wrote in the American Scientist Open Access Forum): MS: "The practice of author payment for open access journals may work for the hard sciences, but it presents major difficulties for various categories of scholars..."Paying to publish journal articles presents difficulties for any author who does not have the money to pay, regardless of field. But it is not an obstacle to providing Open Access (OA) itself:

Although only about 10% of journals are OA journals ("Gold OA Publishing"), over 62% of journals are "Green," meaning that they have already given their green light to all their authors to make their own peer-reviewed final drafts ("postprints") OA by depositing them in their own Institutional (or Central) Repositories (IRs) upon acceptance for publication -- and immediately making them OA ("Green OA Self-Archiving"). Another 29% of journals endorse immediate OA self-archiving of the pre-refereeing preprint, with embargoes of various lengths on making the postprint OA.

(The IR software also makes it possible for all users to request and for all authors to provide almost-instant almost-OA even for Closed or Embargoed Access postprints on an individual Fair-Use basis by means of a semi-automatic "Email Eprint Request" button. That means 62% instant OA plus 38% almost-instant almost-OA.)

OA self-archiving (Green OA) costs nothing. But it should also be pointed out that the majority of Gold OA journals today do not charge for publication -- and those that do, waive the fee if the author cannot afford to pay. (The much larger number of hybrid-Gold publishers -- offering the author the option to pay for Gold OA -- do not waive the Gold OA fee, but most of them are also Green.)

MS: "(1) social sciences and humanities, where grants are smaller and fewer than in the natural and physical sciences."All authors in the social sciences and humanities should therefore provide Green OA (62% instant, 38% almost-instant) to all their articles now, by depositing all their postprints in their IRs immediately upon acceptance for publication.

MS: "(2) graduate students and younger scholars."All graduate students and younger scholars should therefore provide Green OA (62% instant, 38% almost-instant) to all their articles now, by depositing all their postprints in their IRs immediately upon acceptance for publication.

MS: "(3) scholars in the third world."Scholars in the third world should therefore provide Green OA (62% instant, 38% almost-instant) to all their articles now, by depositing all their postprints in their IRs immediately upon acceptance for publication.

MS: "The author-pay model puts people in the above categories (and others) at a serious disadvantage. It would effectively leave out an entire sector of scholarship in the third world. Panglossian arguments about convincing funding agencies to pay for author charges, or transferring university library budgets from subscriptions to author charges, ignore the current financial plight of research in most of the world today."No need of Pangloss for OA: All authors can provide Green OA to articles (62% immediate full OA, 38% almost-immediate almost-OA) by self-archiving their postprints in their IRs, today.

Green OA self-archiving mandates from researchers' own institutions and funders are now on the way worldwide. (The US congress has recently approved a particular big NIH Green OA Mandate, in a Health Bill which has just been vetoed by President Bush, but it may still be adopted if the veto is over-ridden, and could be implemented by NIH and US universities in light of congressional adoption in either case. Six of seven UK research funding councils have already mandated Green OA after it was recommended but not adopted by Parliament. There are already a total of 32 funder and university mandates adopted worldwide, and at least nine more proposed or pending.)

Once adopted globally, these Green OA mandates will immediately provide 62% OA and 38% almost-OA, and the Closed Access embargoes will soon recede under the growing pressure from the powerful and obvious benefits of OA to research, researchers, their institutions, their funders, the tax-paying public that funds them, and the vast R&D industry.

(Eventually, 100% Green OA may even lead to the cancellation of non-OA journals, thereby releasing those institutional subscription funds to pay the much lower costs of Gold OA publishing for an institution's researchers -- costs which reduce to just those of peer-review alone, with all access-provision and archiving now offloaded onto the distributed global network of Green OA IRs.)

But there is no need to keep waiting for Gold OA: Green OA can be provided right now.

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Tuesday, November 13. 2007

Bush vetoes LHHS appropriations bill

"The headline says it all, but here's some detail from Jennifer Loven for the Associated Press":

President Bush, escalating his budget battle with Congress, on Tuesday vetoed a spending measure for health and education programs prized by congressional Democrats....Comments (from Peter Suber):

The president's action was announced on Air Force One as Bush flew to New Albany, Ind., on the Ohio River across from Louisville, Ky., for a speech criticizing the Democratic-led Congress on its budget priorities.

In excerpts of his remarks released in advance by the White House, Bush hammered Democrats for what he called a tax-and-spend philosophy....

More than any other spending bill, the $606 billion education and health measure defines the differences between Bush and majority Democrats. The House fell three votes short of winning a veto-proof margin as it sent the measure to Bush.

Rep. David Obey, the Democratic chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, pounced immediately on Bush's veto.

"This is a bipartisan bill supported by over 50 Republicans," Obey said. "There has been virtually no criticism of its contents. It is clear the only reason the president vetoed this bill is pure politics."

Since winning re-election, Bush has sought to cut the labor, health and education measure below the prior year level. But lawmakers have rejected the cuts. The budget that Bush presented in February sought almost $4 billion in cuts to this year's bill.

Democrats responded by adding $10 billion to Bush's request for the 2008 bill. Democrats say spending increases for domestic programs are small compared with Bush's pending war request totaling almost $200 billion....

Peter Suber: Open Access News-- First, don't panic. This has been expected for months and the fight is not over. Here's a reminder from my November newsletter: "There are two reasons not to despair if President Bush vetoes the LHHS appropriations bill later this month. If Congress overrides the veto, then the OA mandate language will become law. Just like that. If Congress fails to override the veto, and modifies the LHHS appropriation instead, then the OA mandate is likely to survive intact." (See the rest of the newsletter for details on both possibilities.)

-- Also as expected, Bush vetoed the bill for its high level of spending, not for its OA provision.

-- Second, it's time for US citizens to contact their Congressional delegations again. This time around, contact your Representative in the House as well as your two Senators. The message is: vote yes on an override of the President's veto of the LHHS appropriations bill. (Note that the LHHS appropriations bill contains much more than the provision mandating OA at the NIH.)

-- The override vote hasn't yet been scheduled. It may come this week or it may be delayed until after Thanksgiving. But it will come and it's not too early to contact your Congressional delegation. For the contact info for your representatives (phone, email, fax, local offices), see CongressMerge.

-- Please spread the word!

(Page 1 of 2, totaling 16 entries)

» next page

EnablingOpenScholarship (EOS)

Quicksearch

Syndicate This Blog

Materials You Are Invited To Use To Promote OA Self-Archiving:

Videos:

audio WOS

Wizards of OA -

audio U Indiana

Scientometrics -

The American Scientist Open Access Forum has been chronicling and often directing the course of progress in providing Open Access to Universities' Peer-Reviewed Research Articles since its inception in the US in 1998 by the American Scientist, published by the Sigma Xi Society.

The American Scientist Open Access Forum has been chronicling and often directing the course of progress in providing Open Access to Universities' Peer-Reviewed Research Articles since its inception in the US in 1998 by the American Scientist, published by the Sigma Xi Society.

The Forum is largely for policy-makers at universities, research institutions and research funding agencies worldwide who are interested in institutional Open Acess Provision policy. (It is not a general discussion group for serials, pricing or publishing issues: it is specifically focussed on institutional Open Acess policy.)

You can sign on to the Forum here.

Archives

Calendar

Categories

Blog Administration

Statistics

Last entry: 2018-09-14 13:27

1129 entries written

238 comments have been made