Monday, November 30. 2009

From Here to Eternity

Ten years after the creation of the OAI interoperability protocol, 20 years after the creation of the Web and 40 years after the creation of the Net we are still light years from doing what it would take each of us only a few keystrokes to do overnight: freeing our refereed research online.

Ten years after the creation of the OAI interoperability protocol, 20 years after the creation of the Web and 40 years after the creation of the Net we are still light years from doing what it would take each of us only a few keystrokes to do overnight: freeing our refereed research online. It is too late now to do it early, but it's never too late to do it...

La liberté libre...

« Dans tous les cas, il ne s’agira pas de gratuité, mais de libre accès. La nuance est d’importance, car la gratuité n’existe pas... »

« Dans tous les cas, il ne s’agira pas de gratuité, mais de libre accès. La nuance est d’importance, car la gratuité n’existe pas... »Il y a non seulement deux voies vers la liberté d'accès -- la voie dorée de l'édition ouverte et la voie verte de l'autoarchivage ouvert -- mais il y a deux formes ou degrés de la liberté d'accès. (Leurs traductions -- maladroites -- seraient le libre accès « gratuit » [LAG] ("gratis open access") et le libre accès « libre » [LAL] ("libre open access").)

Le LAG est l'accès gratuit en ligne. Le LAL est le LAG plus certains droits de réutilisation, donc la « libération » d'un texte non seulement des barrières d'accès mais aussi des barrières de permission.

Mais la cible principale du mouvement pour le LA est la littérature lectorisée (contrôlée par les comités de lecture): les 2,5 millions d'articles publiés chaque année dans les 25,000 revues scientifiques qui se publient sur notre planète. Pour cette littérature-là, les auteurs/chercheurs ne souhaitent que ce que leurs textes soient accessibles gratuitement en ligne à tout utilisateur pour pouvoir les rechercher, télécharger, lire, imprimer, analyser, citer --

bref, pour utiliser leurs contenus -- mais pas pour réutiliser ou republier ou autrement tripoter avec leurs verbatims dans les sortes de « remixages » que souhaitent le mouvement pour les biens communs créatifs ( « creative commons » ) tels que dans le cas des dessins animés de Disney, remixés par les ados pour ensuite afficher sur youtube.

bref, pour utiliser leurs contenus -- mais pas pour réutiliser ou republier ou autrement tripoter avec leurs verbatims dans les sortes de « remixages » que souhaitent le mouvement pour les biens communs créatifs ( « creative commons » ) tels que dans le cas des dessins animés de Disney, remixés par les ados pour ensuite afficher sur youtube.Donc vive la gratuité, le coeur du LA! Nous l'aurons dès que nos universités et nos subventionnaires de recherche adoptent des politiques obligatoires ( « mandats » ) tel qu'en font déja une centaine.

Reportons la recherche de la liberté « libre » au lendemain de l'arrivée éventuelle de la gratuité pour laquelle nous sommes déja si longtemps en attente...

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Saturday, November 28. 2009

Collini on "Impact on humanities" in Times Literary Supplement

Commentary on:One can agree whole-heartedly with Professor Collini that much of the spirit and the letter of the RAE and the REF and their acronymous successors are wrong-headed and wasteful -- while still holding that measures ("metrics") of scholarly/scientific impact are not without some potential redeeming value, even in the Humanities. After all, even expert peer judgment, if expressed rather than merely silently mentalized, is measurable. (Bradley's observation on the ineluctability of metaphysics applies just as aptly to metrics: "Show me someone who wishes to refute metaphysics and I'll show you a metaphysician with a rival system.")

Collini, S. (2009) Impact on humanities: Researchers must take a stand now or be judged and rewarded as salesmen. Times Literary Supplement. November 13 2009.

The key is to gather as rich, diverse and comprehensive a spectrum of candidate metrics as possible, and then test and validate them jointly, discipline by discipline, against the existing criteria that each discipline already knows and trusts (such as expert peer judgment) so as to derive initial weights for those metrics that prove to be well enough correlated with the discipline's trusted existing criteria to be useable for prediction on their own.

Prediction of what? Prediction of future "success" by whatever a discipline's (or university's or funder's) criteria for success and value might be. There is room for putting a much greater weight on the kinds of writings that fellow-specialists within the discipline find useful, as Professor Collini has rightly singled out, rather than, say, success in promoting those writings to the general public. The general public may well derive more benefit indirectly, from the impact of specialised work on specialists, than from its direct impact on themselves. And of course industrial applications are an impact metric only for some disciplines, not others.

Ceterum censeo: A book-citation impact metric is long overdue, and would be an especially useful metric for the Humanities.

Harnad, S. (2001) Research access, impact and assessment. Times Higher Education Supplement 1487: p. 16.

Harnad, S., Carr, L., Brody, T. & Oppenheim, C. (2003) Mandated online RAE CVs Linked to University Eprint Archives: Improving the UK Research Assessment Exercise whilst making it cheaper and easier. Ariadne 35.

Brody, T., Carr, L., Harnad, S. and Swan, A. (2007) Time to Convert to Metrics. Research Fortnight pp. 17-18.

Harnad, S. (2008) Open Access Book-Impact and "Demotic" Metrics Open Access Archivangelism October 10, 2008.

Harnad, S. (2008) Validating Research Performance Metrics Against Peer Rankings. Ethics in Science and Environmental Politics 8 (11) doi:10.3354/esep00088 Special Issue on "The Use And Misuse Of Bibliometric Indices In Evaluating Scholarly Performance"

Harnad, S. (2009) Open Access Scientometrics and the UK Research Assessment Exercise. Scientometrics 79 (1)

The Elephant in the Room

Fred Friend, Honorary Director Scholarly Communication UCL, wrote in liblicense:

The elephant in the room is Open Access (OA) self-archiving of journal articles by the "Slumbering Giant" -- the universal provider of all the content of the planet's 25,000 peer-reviewed journals: the planet's 10,000 universities and research institutions.

The elephant in the room is Open Access (OA) self-archiving of journal articles by the "Slumbering Giant" -- the universal provider of all the content of the planet's 25,000 peer-reviewed journals: the planet's 10,000 universities and research institutions.

As soon as the Slumbering Giant awakes to the fact that OA is fully within its reach -- all it has to do is to mandate it -- all the fuss about journal affordability, institutional serials crises, and publisher overpricing will fade, for researchers will have access to all refereed research, not just the fraction of it to which their institutions can afford to subscribe today.

And then, maybe, institutions will start canceling, their users' needs no longer being inelastic, thanks to the OA mandates.

And then publishers will cut costs, lower prices, and eventually make a transition to OA publishing, recovering the costs of peer review from institutional publication fees, paid out of a fraction of institutions' windfall subscription cancellation savings.

That's the real elephant in the room, if you like. But as long as we persist in imagining instead that it's something to do with journal pricing, "Big Deals," and the need for pricing reform, we will not only fail to notice the elephant, we will fail to grasp its tail, which is fully within our reach. Instead, we will, like the drunk and the lamp-post, keep fumbling where the elephant isn't (or, like the blind men and the elephant, fail to grasp what it is)!

Ganesh Loxodont

FF: "The phrase "the elephant in the room" was used by a librarian at a recent UK meeting to describe the big issues we were not allowed to discuss about how the current economic crisis is affecting scholarly communication. Representatives of all stakeholder groups present - including publishers - agreed that the economic crisis was hitting them badly, with cost-cutting happening across the board and hopes for growth put on hold. The curious feature of the conversation was that nobody present was able to discuss the one topic which could get us through the crisis and prevent the journals market collapsing, viz. the pricing structure for journal "big deals". Pricing can only be discussed in one-to-one meetings between suppliers and purchasers. It would be easy to blame legislators for anti-trust legislation and the dominance of contract law, but the legal web within which publishing is entwined is of our own making - and I include the academic community in that statement.The elephant in the room is not the prospect of journal subscription cancellations, because as long as researchers need access to peer-reviewed journals, and as long as peer-reviewed journals are accessible only via subscriptions, subscriptions will remain viable, and institutions will just have to keep paying for whatever fraction they can afford of them.

"The importance of this failure to discuss structural and pricing issues is that the dominance of library budgets by "big deal" expenditure has the potential to bring the journal publishing industry to its knees in the same way as sub-prime mortgages did for the banking industry. It will only take a few cancellations of "big deals" by major institutions to make investors nervous about the future of companies heavily dependent upon such deals, and a domino effect could follow. We may be sure that there will be no government bail-out of the journal publishing industry. This scenario would not be good for any of the current stakeholders. The big journal publishing companies have failed to respond positively to the ICOLC initiative on the economic crisis, and the inability to discuss structural and pricing issues in a collaborative way is preventing solutions which have been of benefit in other sectors of the economy. For example, heavily-discounted pricing (by which I do not mean 1%) could ease the burden upon library budgets for one or two years until the overall economic situation improved. No publisher will want to be the first to discuss such solutions, but equallly no publisher will want to be the first to feel the effects of cancellations of its 'big deals'."

The elephant in the room is Open Access (OA) self-archiving of journal articles by the "Slumbering Giant" -- the universal provider of all the content of the planet's 25,000 peer-reviewed journals: the planet's 10,000 universities and research institutions.

The elephant in the room is Open Access (OA) self-archiving of journal articles by the "Slumbering Giant" -- the universal provider of all the content of the planet's 25,000 peer-reviewed journals: the planet's 10,000 universities and research institutions. As soon as the Slumbering Giant awakes to the fact that OA is fully within its reach -- all it has to do is to mandate it -- all the fuss about journal affordability, institutional serials crises, and publisher overpricing will fade, for researchers will have access to all refereed research, not just the fraction of it to which their institutions can afford to subscribe today.

And then, maybe, institutions will start canceling, their users' needs no longer being inelastic, thanks to the OA mandates.

And then publishers will cut costs, lower prices, and eventually make a transition to OA publishing, recovering the costs of peer review from institutional publication fees, paid out of a fraction of institutions' windfall subscription cancellation savings.

That's the real elephant in the room, if you like. But as long as we persist in imagining instead that it's something to do with journal pricing, "Big Deals," and the need for pricing reform, we will not only fail to notice the elephant, we will fail to grasp its tail, which is fully within our reach. Instead, we will, like the drunk and the lamp-post, keep fumbling where the elephant isn't (or, like the blind men and the elephant, fail to grasp what it is)!

Ganesh Loxodont

Friday, November 27. 2009

OA McMemberships, Dismemberment and MC Escher

Gold OA institutional "membership" is incoherent and does not scale. It only gives the illusion of making sense if you think of it locally, and myopically. Annual institutional subscriptions to journals containing the annual outgoing refereed research of all other institutions do not morph into annual institutional memberships for publishing each institution's own outgoing refereed research. There are 25,000 journals and 10,000 institutions! Is every single institution to commit and contract in advance to pay for its authors' (potential) fraction of annual submissions to every single journal? Is that a "membership" or a distributed dismemberment? And is every journal to commit and contract in advance to accept every institution's annual fraction of submissions? (Is that peer review?) This is a global oligopolistic illusion that would fit publishers just about as well as it would fit McDonalds, except there are at least 25,000 different journals to "join", and institutions each have thousands of author-consumers with diverse dietary needs, varying day to day and year to year.

Gold OA institutional "membership" is incoherent and does not scale. It only gives the illusion of making sense if you think of it locally, and myopically. Annual institutional subscriptions to journals containing the annual outgoing refereed research of all other institutions do not morph into annual institutional memberships for publishing each institution's own outgoing refereed research. There are 25,000 journals and 10,000 institutions! Is every single institution to commit and contract in advance to pay for its authors' (potential) fraction of annual submissions to every single journal? Is that a "membership" or a distributed dismemberment? And is every journal to commit and contract in advance to accept every institution's annual fraction of submissions? (Is that peer review?) This is a global oligopolistic illusion that would fit publishers just about as well as it would fit McDonalds, except there are at least 25,000 different journals to "join", and institutions each have thousands of author-consumers with diverse dietary needs, varying day to day and year to year. Part of the illusion of coherence comes from thinking in terms of journal-fleet publishers instead of individual journal article submissions. But this is merely another variant of the "Big Deal" strategy that has done nothing to solve either the accessibility or the affordability problem. The reality is that (Gold) OA publishing is premature today, except as a proof of principle. What is needed first is for universal (Green) OA self-archiving mandates to be adopted by institutions and funders. That will provide universal (Green) OA, which may eventually generate cancellation pressure that will induce journals to cut obsolete costs and products/services by downsizing to just providing peer review, paid for by individual institutions on an individual outgoing article basis out of a fraction of their annual windfall savings from their institutional subscription cancellations. To buy into "memberships" with fleet publishers now, pre-emptively, and at current prices, while the money is still tied up in subscriptions (which cannot, of course, be cancelled in advance, before OA) is both penny- and pound-foolish -- and downright absurd if a "member" institution has not even first mandated Green OA self-archiving for all of its own refereed research output...

Part of the illusion of coherence comes from thinking in terms of journal-fleet publishers instead of individual journal article submissions. But this is merely another variant of the "Big Deal" strategy that has done nothing to solve either the accessibility or the affordability problem. The reality is that (Gold) OA publishing is premature today, except as a proof of principle. What is needed first is for universal (Green) OA self-archiving mandates to be adopted by institutions and funders. That will provide universal (Green) OA, which may eventually generate cancellation pressure that will induce journals to cut obsolete costs and products/services by downsizing to just providing peer review, paid for by individual institutions on an individual outgoing article basis out of a fraction of their annual windfall savings from their institutional subscription cancellations. To buy into "memberships" with fleet publishers now, pre-emptively, and at current prices, while the money is still tied up in subscriptions (which cannot, of course, be cancelled in advance, before OA) is both penny- and pound-foolish -- and downright absurd if a "member" institution has not even first mandated Green OA self-archiving for all of its own refereed research output...Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Wednesday, November 25. 2009

Institutional vs. Central Repositories: 2 (of 2)

Simeon Warner (Arxiv, Cornell) wrote in JISC-REPOSITORIES:

Simeon Warner (Arxiv, Cornell) wrote in JISC-REPOSITORIES:SW: "Lots of money is being spent on institutional repositories and, so far, the return on that investment is quite low."Low compared to what? It is undeniable that most of the thousands of institutional repositories are languishing near empty. The only exceptions are the fewer than a hundred mandated ones.

But that's the point. What's needed is more mandates, not more "investment." Mandates are what will bring the return on the investment.

And there is another crucial point, constantly overlooked: Most central repositories are languishing near-empty too! The only reason it looks otherwise is that usually a subject repository has more content than an institutional repository. But the reason for that is quite simple:

The annual worldwide output of an entire field is incomparably bigger than the annual output of any single institution. So when an institution contains no more than the usual low baseline for annual unmandated self-archiving (c. 15% of total annual research output) it has a much smaller absolute number of annual deposits than a central repository (even though that too contains only the very same low baseline 15% of the annual output in the field as a whole, across all institutions, worldwide). (This is the "denominator fallacy.")

Yes, I know the physics Arxiv is an exception (with an incomparably higher unmandated central deposit rate for several of its subfields). But that's the point: Arxiv is, and has been, an exception for nearly 20 years now. No point continuing to hold our breath and hope that the longstanding spontaneous (unmandated) self-archiving practices of (some fields of) physics will be adopted by other fields. It's not happening, and 20 years is an awfully long time.

PubMedCentral (PMC) might -- and I say might, because no one has actually done the calculation -- possibly be doing better than the 15% default baseline, but that's because PMC deposit is mandatory (by NIH and other funders), not because PMC is central!

(Indeed, my whole point is that the NIH and kindred biomedical self-archiving mandates would get incomparably more bang for the buck if they mandated institutional deposit -- and then just harvested/imported to PMC -- rather than needlessly insisting on direct central (PMC) deposit. For if NIH mandated institutional deposit, it would help stir the Slumbering Giant -- the universal providers of all research, funded and unfunded, in all fields, namely, the world's universities and research institutes -- into mandating deposit for all the rest of their annual research output too.

SW: "I am still optimistic that institutional repositories will become more useful but for that to happen there need to be useful worldwide (not just UK or European focused because that doesn't match research communities) disciplinary services and portals built on top them. The Catch 22 here is that disciplinary services have exactly the same funding and sustainability issues that disciplinary repositories have."What institutional repositories need is deposit mandates, so they can have content that is worth building services on top of. It's not the potential (or the funding) for services that's missing, it's the content (85%). And to get that content deposited, we need (convergent) institutional and funder deposit mandates.

SW: "My group manages both Cornell's eCommons institutional repository and the arXiv.org disciplinary repository. The effective cost per item [footnote 1] submitted is more than 10 times higher for the institutional repository than the disciplinary repository and the benefit/utility/visibility is lower. However, I know exactly who should and will fund eCommons (Cornell), and that nicely matches the vested interest (Cornell). The community benefit from arXiv.org is enormous and the effective cost per new item very low (<$7/item), but given 60k new items per year that is a significant cost and sustainability is a challenge."The cost-per-item stats are funny-money. Cornell's problem is not that it costs too much per item to deposit, it's that the deposits are not being done, because Cornell has no mandate. That makes the ratio of IR costs to IR items unsatisfying, of course, but you are missing the real cause!

Moreover, if all institutions had mandates, the (equally small) cost per deposited item would be distributed across the planet's 10K institutions, instead of concentrated on a few central repositories (most near-empty, just like Cornell's institutional one, plus a [very] few serendipitously overstocked central ones, like Arxiv).

SW: "I think the best example of a disciplinary service over institutional repositories is RePEc in economics. This predates OAI and our current conception of IRs but fits the model: institutions (typically economics departments [footnote 2]) host articles and expose metadata/data via a standard interface. The institutionally held content is genuinely useful to the economics community because of the disciplinary services."All true. (And note that your "best example" is a central service over distributed institutional repositories, not a central repository in which authors deposit directly! Citeseer is another excellent example, in computer science, a field that has been self-archiving even longer than physics and economics.)

But here again, we have a community that has been self-archiving (spontaneously, and institutionally) unmandated for almost as long as Arxiv users. And again, this admirable practice has not generalized to other fields.

What physicists and economists (and computer scientists) seem to have in common is that they find the practice of publicly disseminating working papers -- unrefereed preprints -- useful and productive. That is splendid. I do too. But the majority of fields -- and hence of researchers -- do not find publicly disseminating their unrefereed drafts useful. And you certainly cannot mandate making authors' unrefereed drafts public; in some biomedical fields that might even be dangerous.

But you can mandate making refereed final drafts (published or accepted for publication) public: they are already being made public, since they're being published. So all you need to do is make it mandatory that they also be made freely accessible online (OA), so that not only subscribers can access and use them but all potential users can.

And that is what OA is about.

SW: "At the end of the day, researchers want and will use disciplinary services (look at usage stats for arXiv, ADS, SPIRES, RePEc, PMC, SSRN vs IRs). They probably don't care whether the items themselves are stored centrally or institutionally."Correct, for users. But users do care whether the items are accessible at all. And that's what deposit mandates (and OA itself) are for.

And authors do care about whether they need to do multiple deposits; and institutions do care about whether they host their own research output.

So it does matter whether deposit is mandated institutionally or centrally, by both institutions and funders.

The difference is not in functionality, but in content. And you have no functionality if you have no content!

SW: "Some of Stevan's arguments miss key points:"

sh: "(1) Institutions are the universal providers of all research output -- funded and unfunded, across all subjects, all institutions, and all nations."

SW: "Not true, researchers are the universal providers of research output. They often work in teams that span multiple institutions and their first allegiance is often to their discipline rather than their institution."That is (sometimes) true, but trivial. Researchers are answerable to their own institutions (employers) when it comes to the tallying of their research output for research performance assessment. (You may be more loyal to "Physics" than to Cornell U, but it is Cornell, not "Physics," that hires you, pays your salary, and evaluates your productivity; it is "for" Cornell that you "publish or perish" even if your heart belongs to "Physics.")

sh: "(3) OAI-compliant Repositories are all interoperable.

"(7) The metadata and/or full-text deposits of any OAI compliant repository can be harvested, exported or imported to any OAI compliant repository."

SW: "Interoperable to a point, and I say that as one of the creators of OAI-PMH. There is plenty of experience showing how hard it is to maintain large harvested collections and merge varying metadata (e.g. OAIster, NSDL). Institutional repositories are often managed with scant attention to maintaining interoperability, managers change the OAI-PMH base URL on a whim or do not monitor for errors. Full-text often has copyright/license issues preventing import into other repositories. "All extremely minor (and readily remediable) points, compared to the real problem of institutional repositories, which is not that they are errorful but that they are EMPTY. (No point even fixing the errors while content is so impoverished. And once content is rich enough, there's the requisite motivation to clean up errors and maximize interoperability -- and services.)

sh: "(11) The solution is to fix the funder locus-of-deposit specs, not to switch to central locus of deposit."

SW: "The solution is to build disciplinary services (either on disciplinary repositories or over harvested content) that are sufficiently useful to motivate researchers to submit of their own free will."The solution to what problem? The problem I am addressing ('lo these nigh on 20 years) is the absence of the target content over which the putative services are built. Arxiv does not suffer from this problem -- and saints be praised for that -- but that doesn't help the rest of us!

Yes, all kinds of powerful new services would be more than welcome (and will come) -- but they are useless in the absence of the content on which they are meant to operate.

And it is not researchers as users that are the problem. It is researchers as authors -- hence content-providers, depositors -- that are the problem. The reason they are failing to deposit is not -- let me save you the trouble of waiting more years to find out that this is so -- because the user-services (or even the author-services) are not spiffy enough yet.

They are failing to deposit because their fingers are "paralyzed" (for at least 34 reasons):

And the cure for that paralysis is deposit mandates: "keystroke mandates" from their institutions and funders.Harnad, S. (2006) Opening Access by Overcoming Zeno's Paralysis in Jacobs, N., Eds. Open Access: Key Strategic, Technical and Economic Aspects. Chandos.

And one of the (many) things holding up the universal adoption of those keystroke mandates is funders needlessly competing with institutions for their researchers' reluctant keystrokes by mandating central deposit, hence stoking instead of soothing paralyzed authors' (rightful) resistance to the prospect of having to do divergent multiple deposit at central sites instead of convergent one-time local deposit in their own institutional repository.

SW: "(footnote 1) I think effective cost per new item is a good measure of repository cost because almost all effort beyond relatively fixed costs of keeping the system going tends to be dealing with new items. I calculate as operating budget over some period divided by number of new items in that period."But surely you also see that the cost per item deposited depends on the overall number of items deposited!

SW: "(footnote 2) I'm pleased to say that the section of arXiv that overlaps with RePEc -- Quantitative Finance (q-fin) -- is also included in RePEc (http://ideas.repec.org/s/arx/papers.html)."Splendid. And I wish both Arxiv and RePec all the best in taking their very useful place among (many) central collections and service-providers.

But let the one-time locus of deposit be where it belongs, and needs to be: in the researcher's own local institutional repository. And let that be the designated convergent locus of deposit for both institutional and funder mandates.

Amen

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Institutional vs. Central Repositories: 1 (of 2)

Chris Armbruster wrote (in the American Scientist Open Access Forum):

(2) The ones who need to reconsider their strategy are the (few) research funders who have needlessly and counterproductively stipulated that locus of deposit should be central rather than institutional.

(3) Institutions are the universal providers of all research output -- funded and unfunded, across all subjects, all institutions, and all nations.

(4) Institutions have a vested interest in hosting, monitoring, showcasing and archiving their own research output.

(5) OAI-compliant Repositories are all interoperable.

(6) Either funders or institutions can in principle stipulate any locus of deposit for a mandate, either institutional or central.

(7) But mandates are still growing too slowly, and one big reason is that no one wants to do -- or mandate -- multiple deposit.

(8) There are potentially multiple, diverse and divergent central loci for any piece of research output: subject collections, national collections, funder collections, multidisciplinary collections, etc.

(9) The metadata and/or full-text deposits of any OAI-compliant repository can be harvested, exported or imported to any OAI-compliant repository.

(10) The natural, economical, rational and systematic solution (one-to-many, unitary-local -- multiple-distal) is for all researchers to deposit locally, in their own institional repository -- and for distal central collections to harvest, import or export -- not the reverse (many-to-one, distal to local, willy-nilly, with institutions having to back-harvest their very own output from here, there and everywhere!), or both, or neither.

(11) The only thing that stands in the way of that optimal solution -- whereby institutional and funder mandates can collaborate, converge, and mutually reinforce one another instead of diverging and competing -- is the arbitrary and ill-thought-through requirement by some funders (but by no means all) to deposit centrally instead of institutionally.

(12) This obstacle is neither a functional one (it has nothing whatsoever to do with the relative functionality of institutional and central repositories -- they are interoperable and equipotent in every respect) nor a "cultural" one (since self-archiving culture is still very new and all too rare): the problem is simply the needless adoption of arbitrary and ill-thought-out locus-of-deposit requirements by some of the initial funders.

(13) The solution is to fix the funder locus-of-deposit specs, not to switch to central locus of deposit.

(14) Prediction: The notion of a "central repository" -- new as it is -- is already obsolescent: Is Google a "central repository" or merely a harvester of local content?

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

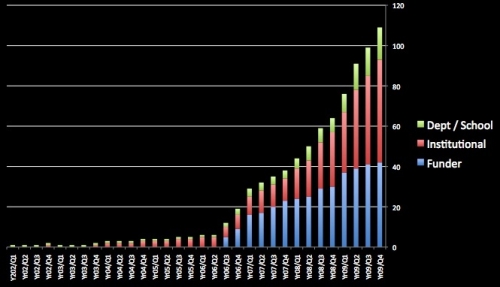

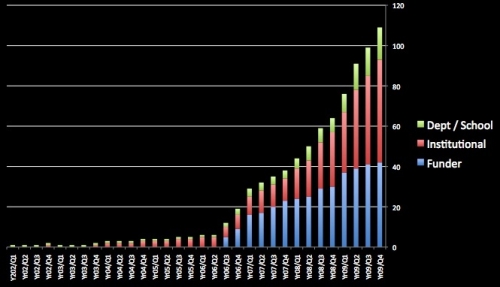

CA: "Much hope and a lot of money has been invested in institutional repositories - but, for example, in the UK the significant mandates are now research funder mandates and all the life science RCUKs have joined UK PMC. It would thus seem important and urgent that IRs reconsider their strategy and take a closer look at the idea of being a research repository or joining forces for building a national (or regional) system."(1) It is not at all clear that the "significant mandates" are the funder mandates, especially in view of the past year's burst in institutional mandates (UCL, Harvard, MIT, Stanford...). See Alma Swan's latest graph of mandate growth in ROARMAP:

Armbruster, C and Romary, L (2009) Comparing Repository Types: Challenges and Barriers for Subject-Based Repositories, Research Repositories, National Repository Systems and Institutional Repositories in Serving Scholarly Communication

Click here for Latest Growth Graph Update

(2) The ones who need to reconsider their strategy are the (few) research funders who have needlessly and counterproductively stipulated that locus of deposit should be central rather than institutional.

(3) Institutions are the universal providers of all research output -- funded and unfunded, across all subjects, all institutions, and all nations.

(4) Institutions have a vested interest in hosting, monitoring, showcasing and archiving their own research output.

(5) OAI-compliant Repositories are all interoperable.

(6) Either funders or institutions can in principle stipulate any locus of deposit for a mandate, either institutional or central.

(7) But mandates are still growing too slowly, and one big reason is that no one wants to do -- or mandate -- multiple deposit.

(8) There are potentially multiple, diverse and divergent central loci for any piece of research output: subject collections, national collections, funder collections, multidisciplinary collections, etc.

(9) The metadata and/or full-text deposits of any OAI-compliant repository can be harvested, exported or imported to any OAI-compliant repository.

(10) The natural, economical, rational and systematic solution (one-to-many, unitary-local -- multiple-distal) is for all researchers to deposit locally, in their own institional repository -- and for distal central collections to harvest, import or export -- not the reverse (many-to-one, distal to local, willy-nilly, with institutions having to back-harvest their very own output from here, there and everywhere!), or both, or neither.

(11) The only thing that stands in the way of that optimal solution -- whereby institutional and funder mandates can collaborate, converge, and mutually reinforce one another instead of diverging and competing -- is the arbitrary and ill-thought-through requirement by some funders (but by no means all) to deposit centrally instead of institutionally.

(12) This obstacle is neither a functional one (it has nothing whatsoever to do with the relative functionality of institutional and central repositories -- they are interoperable and equipotent in every respect) nor a "cultural" one (since self-archiving culture is still very new and all too rare): the problem is simply the needless adoption of arbitrary and ill-thought-out locus-of-deposit requirements by some of the initial funders.

(13) The solution is to fix the funder locus-of-deposit specs, not to switch to central locus of deposit.

(14) Prediction: The notion of a "central repository" -- new as it is -- is already obsolescent: Is Google a "central repository" or merely a harvester of local content?

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Tuesday, November 24. 2009

Open Access Mandate Sweepstakes: 109 And Growing

Latest Green Open Access Mandates in  ROARMAP:

ROARMAP:

Oberlin College (institutional)

University of Kansas (institutional total now 51)

Brigham Young University 1, 2 (departmental total now 16)

Institutional + Departmental + Funder: 109

University of Central Florida (thesis total now 37)

All mandates: 146 adopted (15 more proposed -- including the blockbuster US Federal Research Public Access Act [FRPAA] multi-funder mandate proposal, for which momentum is growing)

ROARMAP:

ROARMAP:Oberlin College (institutional)

University of Kansas (institutional total now 51)

Brigham Young University 1, 2 (departmental total now 16)

Institutional + Departmental + Funder: 109

University of Central Florida (thesis total now 37)

All mandates: 146 adopted (15 more proposed -- including the blockbuster US Federal Research Public Access Act [FRPAA] multi-funder mandate proposal, for which momentum is growing)

Monday, November 23. 2009

Chronique du libre accès

26e Colloque annuel de l’Association des administratrices et des administrateurs de recherche universitaire du Québec (ADARUQ) Château Laurier, Québec 19 novembre 2009

26e Colloque annuel de l’Association des administratrices et des administrateurs de recherche universitaire du Québec (ADARUQ) Château Laurier, Québec 19 novembre 2009« Accès libre et auto-archivage : carnet de bord de bonnes pratiques »

Cet atelier porta sur la problématique de l'accès libre à la documentation scientifique sous format numérique. Y furent présentés l'historique de l'accès libre, les concepts qui le délimitent ainsi que les outils mis à la disposition de la communauté de recherche afin de rendre publics les résultats de la recherche subventionnée. Stevan Harnad, titulaire de la Chaire de recherche du Canada en sciences cognitives à l'UQAM, présenta ce portrait détaillé.

Tanja Niemann, ÉRUDIT, et Michael Eberle-Sinatra, Professeur, UDEM, SYNERGIES de l'Université de Montréal présentèrent ces deux plateformes d'accès libre, instaurées grâce au soutien financier des fonds québécois et de la Fondation canadienne pour l'innovation (FCI).

Comment un établissement de recherche peut-il par ailleurs établir une archive institutionnelle de publications numériques ? L'expérience d'Archipel, l'Archive de publications électroniques de l'UQAM, fut relatée par Magada Fusaro, titulaire de la Chaire Unesco-Bell en communication et développement international et présidente-fondatrice du Comité institutionnel sur l'auto-archivage qui a supervisé les travaux préliminaires au lancement d'Archipel, ainsi que par Marc Couture, Professeur à la TÉLUQ.

Modératrice et responsable : Dominique Michaud, UQAM

Participants :

Stevan Harnad, Professeur, UQAM Chronique du Libre Accès

Tanja Niemann, ÉRUDIT

Michael Eberle-Sinatra, Professeur, UDEM, SYNERGIES

Magda Fusaro, Professeure, UQAM

Marc Couture, Professeur, TELUQ

Tuesday, November 17. 2009

On Self-Selection Bias In Publisher Anti-Open-Access Lobbying

Response to Comment by Ian Russell on Ann Mroz's 12 November 2009 editorial "Put all the results out in the open" in Times Higher Education:

Update Jan 1, 2010: See Gargouri, Y; C Hajjem, V Larivière, Y Gingras, L Carr,T Brody & S Harnad (2010) “Open Access, Whether Self-Selected or Mandated, Increases Citation Impact, Especially for Higher Quality Research”

Update Feb 8, 2010: See also "Open Access: Self-Selected, Mandated & Random; Answers & Questions"

"It’s not 'lobbying from subscription publishers' that has stalled open access, it’s the realization that the simplistic arguments of the open access lobby don’t hold water in the real world... [with] open access lobbyists constantly referring to the same biased and dubious ‘evidence’ (much of it not in the peer reviewed literature)."Please stay tuned for more peer-reviewed evidence on this, but for now note only that the study Ian Russell selectively singles out as not "biased or dubious" -- the "first randomized trial" (Davis et al 2008), which found that "Open access [OA] articles were no more likely to be cited than subscription access articles in the first year after publication” -- is the study that argued that in the host of other peer-reviewed studies that have kept finding OA articles to be more likely to be cited (the effect usually becoming statistically significant not during but after the first year), the OA advantage (according to Davis et al) is simply a result of a self-selection bias on the part of their authors: Authors selectively make their better (hence more citeable) articles OA.

Russell selectively cites only this negative study -- the overhastily (overoptimistically?) published first-year phase of a still ongoing three-year study by Davis et al -- because its result sounds more congenial to the publishing lobby. Russell selectively ignores as "biased and dubious" the many positive (peer-reviewed) studies that do keep finding the OA advantage, as well as the critique of this negative study (as having been based on too short a time interval and too small a sample, not even long enough to replicate the widely reported effect that it was attempting to demonstrate to be merely an artifact of a self-selection bias). Russell also selectively omits to mention that even the Davis et al study found an OA advantage for downloads within the first year -- with other peer-reviewed studies having found that a download advantage in the first year translates into a citation advantage in the second year (e.g., Brody et al 2006). (If one were uncharitable, one might liken this sort of self-serving selectivity to that of the tobacco industry lobby in its time of tribulation, but here it is not public health that is at stake, merely research impact...)

But fair enough. We've now tested whether the self-selected OA impact advantage is reduced or eliminated when the OA is mandated rather than self-selective. The results will be announced as soon as they have gone through peer review. Meanwhile, place your bets...

Brody, T., Harnad, S. and Carr, L. (2006) Earlier Web Usage Statistics as Predictors of Later Citation Impact. Journal of the American Association for Information Science and Technology (JASIST) 57(8) pp. 1060-1072.

Davis, PN, Lewenstein, BV, Simon, DH, Booth, JG, & Connolly, MJL (2008) Open access publishing, article downloads, and citations: randomised controlled trial British Medical Journal 337: a568

Harnad, S. (2008) Davis et al's 1-year Study of Self-Selection Bias: No Self-Archiving Control, No OA Effect, No Conclusion.

Hitchcock, S. (2009) The effect of open access and downloads ('hits') on citation impact: a bibliography of studies.

(Page 1 of 2, totaling 16 entries)

» next page

EnablingOpenScholarship (EOS)

Quicksearch

Syndicate This Blog

Materials You Are Invited To Use To Promote OA Self-Archiving:

Videos:

audio WOS

Wizards of OA -

audio U Indiana

Scientometrics -

The American Scientist Open Access Forum has been chronicling and often directing the course of progress in providing Open Access to Universities' Peer-Reviewed Research Articles since its inception in the US in 1998 by the American Scientist, published by the Sigma Xi Society.

The American Scientist Open Access Forum has been chronicling and often directing the course of progress in providing Open Access to Universities' Peer-Reviewed Research Articles since its inception in the US in 1998 by the American Scientist, published by the Sigma Xi Society.

The Forum is largely for policy-makers at universities, research institutions and research funding agencies worldwide who are interested in institutional Open Acess Provision policy. (It is not a general discussion group for serials, pricing or publishing issues: it is specifically focussed on institutional Open Acess policy.)

You can sign on to the Forum here.

Archives

Calendar

Categories

Blog Administration

Statistics

Last entry: 2018-09-14 13:27

1129 entries written

238 comments have been made