Wednesday, July 9. 2008

Batch Deposits in Institutional Repositories (the SWORD protocol)

In the context of Nature's just-announced offer to do proxy deposits for its authors, Peter Suber has asked Les Carr of EPrints to comment on whether the software has the capability of downloading and uploading deposits automatically, in batch mode, rather than just singly, with the keystrokes done by hand.

In the context of Nature's just-announced offer to do proxy deposits for its authors, Peter Suber has asked Les Carr of EPrints to comment on whether the software has the capability of downloading and uploading deposits automatically, in batch mode, rather than just singly, with the keystrokes done by hand.Les Carr's reply is affirmative:

"Both EPrints and DSpace allow batch uploads, but more to the point, both of them support the new SWORD [Simple Web-service Offering Repository Deposit] protocol for making automatic deposits in repositories. We (the SWORD developers) very much hope that we will be able to work with established discipline [i.e., central] repositories to allow automatic feed through of deposits from Institutional Repositories into Discipline Repositories and vice versa."

Tuesday, July 8. 2008

Automatic search for OA versions of cited articles

Matt Cockerill (publisher of BioMed Central) makes the following comment on "The #1 Myth About Open Access":  That's exactly why Mike Jewell created Paracite. It would be a piece of cake to set up a bit of software that automatically transformed text that one highlights in a reference list into a Paracite or Google Scholar query. The only reason no one has yet bothered to create that piece of software is that most of that potential content is not yet OA. But Green OA self-archiving and mandates will take care of that...

That's exactly why Mike Jewell created Paracite. It would be a piece of cake to set up a bit of software that automatically transformed text that one highlights in a reference list into a Paracite or Google Scholar query. The only reason no one has yet bothered to create that piece of software is that most of that potential content is not yet OA. But Green OA self-archiving and mandates will take care of that...

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

You take issue with Mike Dunford's comment: "Just what is open access?... In an open access journal, there's no charge for reading articles..." and note that you feel that author deposit of manuscripts in open access repositories, in parallel to the existing subscription-based pay-to-access journals, is a faster and surer way to achieve open access.

But do you not agree that when a reader of an article spots an interesting item in a reference list, and clicks to follow a link to the article concerned, it does not "feel" like open access when they are faced with a publisher's pay-wall asking for a subscription or per-article fee to view the article. Of course, there are several ways they may be able to view a version of the article without paying. The would-be reader could search the net to see if they can track down a free copy of the article in a repository; they can send an email request to the author (who is hopefully not on holiday and has a legally sharable electronic version to hand); or they can try their luck down at their local library. Fair enough. But you must have some sympathy with a reader who would prefer simply to click a link and get straight to the article concerned, without being challenged to provide credit card details. It's not such a bad definition of open access.

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Thursday, October 18. 2007

Time to Update the BBB Definition of Open Access

On Mon, 15 Oct 2007, Frederick Friend wrote:[Update: See new definition of "Weak" and "Strong" OA, 29/4/2008]

SUMMARY: The definition of Open Access (OA) is still young, and not yet etched in stone; it stands only to benefit from a rational, corrective update. Parts of the (increasingly gilded) BBB formulation turn out to have been unnecessary, counterproductive, and even incoherent. The right to re-publish, re-sell and create derivative works may be essential for Free Online Scholarship (FOS), and for the Creative Commons, but they are not essential for OA, and it would be an unnecessary, self-imposed handicap to insist that they should be, merely raising barriers to OA where there are and need be none. It is a good idea for authors to retain extra rights for their published articles, wherever possible, but it is definitely not a necessary prerequisite for Green OA self-archiving, nor for Green OA self-archiving mandates.

For the 62% of articles published in the Green journals that have explicitly endorsed the immediate OA self-archiving of the author's postprint, no further rights are needed to self-archive it, hence no further rights need to be negotiated as a precondition. And robotic harvesting and data-mining (Google, Scirus, OAIster) all come with the free online territory as surely as individual usage does.

For the 38% of articles published in non-Green journals, authors can still deposit them in their Institutional Repositories (IRs), immediately upon acceptance for publication, setting access as Closed Access. With the help of the IR's "Email Eprint Request" Button, this provides for (1) accessing, (2) reading, (3) downloading, (4) storing (5) printing-off, (6) individual data-mining, and (7) re-using content (but not text) in further publications. That is still not OA; it is only almost-OA: Missing is full-text (8*) robotic harvesting and (9*) robotic data-mining.

If all or most universities already mandated exception-free immediate-deposit as above (Open Access for the Green 62% and Closed Access for the non-Green 38%), there would be no problem at all about then going still further and trying to negotiate the retention of more rights -- even unnecessary ones! But instead declaring successful rights retention to be a precondition (by BBB "definition") would simply hamstring both self-archiving and the adoption of self-archiving mandates, and hence the advent of OA itself.

"I also agree with [Peter Suber, Peter Murray-Rust and Robert Kiley] that the UKPMC re-use agreement is vital for future academic developments. With hindsight we were too slow to pick up on the significance of the changes to copyright transfer agreements in the 1990s by which authors now assign all electronic rights to publishers. Blanket assigning of electronic rights has created and is still creating barriers in the electronic re-use of subscription content. We cannot afford to make the same mistake of neglect on the arrangements for academic re-use of OA content, whether green or gold."I am afraid that this is more a matter of misunderstanding than of disagreement:

(1) The disagreement (with PS, PM-R and RK) was not about whether or not it is a good idea for the author to retain certain electronic rights. (It is a good idea for the author to do so, wherever possible. However, rights-retention is not a necessary prerequisite for Green OA self-archiving, nor for Green OA self-archiving mandates. Hence it would be a big mistake to imply otherwise: i.e., to imply that authors cannot self-archive, and/or their institutions/funders cannot mandate that they self-archive, until/unless the author successfully negotiates rights-retention. That would not only be incorrect, but it would be a gratuitous deterrent to self-archiving and to self-archiving mandates, hence to OA.)I am sorry to sound like a pedant, but these details are devilishly important, and need to be understood quite explicitly:

(2) The disagreement was instead about:(2a) whether or not certain electronic rights (not the same rights as in (1), above, by the way!), provided by certain Gold OA copyright agreements, were indeed necessary in order for research and researchers to derive the full benefits of OA (they are not)

and

(2b) whether or not there existed any further necessary rights or capabilities over and above those already inherent in Green OA self-archiving -- rights that therefore either had to be successfully negotiated with a non-OA publisher or had to be purchased from a Gold OA publisher in order to render an article OA (there are none)

Concerning (1) (i.e., rights retention as a prerequisite to Green OA self-archiving), what I said was that for the 62% of articles published in Green journals -- i.e., those that have explicitly endorsed the immediate OA self-archiving of the postprint (whether final draft or PDF) -- no further rights are needed to self-archive them, hence no further rights need to be negotiated as a precondition for self-archiving. The self-archived work is "protected" by standard copyright, and it is also OA, with all the attendant usage capabilities (of which I listed nine, covering all uses that research and researchers require, which are also all the self-same uses for which OA itself was proposed).

I also said that for the 38% of articles published in non-Green journals -- i.e., those journals that have not yet explicitly endorsed the immediate OA self-archiving, by the author, of the postprint (whether final draft or PDF) -- the strategy that I recommend is (a) mandated Immediate Deposit, Optional Closed Access and reliance on the semi-automatic "Email Eprint Request" Button to cover usage needs during the embargo.

I agreed, however, that it is possible to disagree on this strategic point, and to prefer instead (b) to try to negotiate rights retention with the non-Green publisher or else to (c) publish instead with a Gold OA publisher that provides the requisite rights. There is of course nothing at all wrong with strategy (b) and/or (c) as a matter of individual choice in each case. But strategy (a) is intended as the default strategy for facilitating exception-free self-archiving, and especially for facilitating the adoption of legal-objection-immune, exception-free self-archiving mandates.

So far, the only "right" at issue is the right to self-archive -- the right to provide immediate Green OA. It is that Green OA that I was arguing was sufficient to provide full OA (and the 62% of journals that are Green have already endorsed it.)

But now we come to (2): certain "re-use" rights and capabilities that purportedly go beyond those that already come with the territory, with Green OA self-archiving. Now we are no longer speaking of the right to self-archive, obviously, but of the right to create certain kinds of "derivative works" that one may re-publish (and perhaps even re-sell).

What I said there was that the right to re-publish, re-sell, and create derivative works for re-publication or re-sale is not part of OA. They are something extra (approaching certain kinds of Creative Commons Licenses). Most important, those extra rights are not necessary for research and researchers, they go far beyond OA, and they would handicap OA's already too-slow progress towards universality if added as a gratuitous extra precondition on counting as "full-blooded OA."

The very idea that these extra rights are needed comes not from the intuitions of the library community about how to include subscription content in course-packs -- those needs are trivially fulfilled by inserting the URLs of Green OA postprints in the course-packs, instead of inserting the documents themselves! -- but from intuitions about data-mining from (some sectors) of the biological and chemical community (inspired largely by the data-sharing of the human genome project as well as similar chemical-structure data-sharing in chemistry).

There are very valid concerns about research data sharing: note that such data are typically not contained in published articles, but are supplements to them that until the online era had no way of being published at all, because the data-sets were too big. So the concern is about licensing these data to make them openly accessible and to prevent their ever becoming subject to the same access-barriers as subscription content.

This is a very important and valid goal but, strictly speaking, it is not an OA matter, because these research data are not part of the published content of journal articles! So, yes, providing online access to these data does definitely require explicit rights licensing, but no one is stopping their authors (the holders of the data) from adopting those licenses! (The appropriate CC licenses exist.) And there's certainly no reason to pay a Gold OA publisher for those extra rights or rights agreements for data, which are hitherto unpublished content that can now be licensed and self-archived directly.

This brings us to the second case, the case that I suspect those who see an extra rights problem here have most in mind: It concerns the content of published journal articles, both inasmuch as the articles may indeed contain some primary data, as opposed to merely summaries, descriptions and analyses, and inasmuch as the article texts themselves can be seen as constituting potential data. This is where data-mining rights and derivative-works rights come in: "Naked" Green OA -- simply making these published full-texts accessible online, free for all -- is not enough (think these theorists) to guarantee that robots can data-mine their contents and that the results can be made accessible (published, or re-published) as "derivative works," unless those extra "rights" (to data-mine and create derivative works) are explicitly licensed.

My reply is very simple: robotic harvesting and data-mining come with the free online territory as surely as individual use does. Remember that we are talking about authors' self-archived postprints here, not the publishers' proprietary PDFs, whether Gray or Gold. If the journal is Green, it endorses the author's right to deposit the postprint in his OA IR. The rest (individual accessibility, Google, Scirus, OAIster, robotic harvestability, and data-mining) all come with that Green OA territory. So the contention is not about the Green OA self-archiving of the postprints published in the 62% of journals that are Green.

Is the contention then about the 38% of articles published in non-Green journals? I agree at once that if the author feels he cannot make those articles Green OA immediately, and instead deposits them as Closed Access, then, with the help of the IR's "Email Eprint Request" Button, only re-use capabilities (1)-(7) [(1) accessing, (2) reading, (3) downloading, (4) storing (5) printing, (6) individual data-mining, and (7) re-using content (but not text) in further publications] are possible.

This is definitely not OA; it is merely almost-OA. Missing is full-text (8*) robotic harvesting and (9*) robotic data-mining. If, to try to avoid this outcome, an author who fully intends to deposit his postprint immediately upon acceptance regardless of the outcome, first elects to try to negotiate the retention of more rights with his publisher -- or even elects to publish with a paid Gold publisher rather than deposit as Closed Access, with almost-OA -- that's just fine!That author is intent on self-archiving either way. The problem with holding out for and insisting upon more rights is (1) the author who would not deposit except if the publisher was Green (or Gold), and -- even more important -- (2) the institutions that would not mandate depositing except if all publishers were already Green (or Gold).

It is those authors and those institutions that are the main retardants on universal OA today. If most universities already mandated immediate-deposit either way (OA or CA), I would do nothing but applaud the efforts to negotiate the retention of more rights -- even unnecessary ones! -- But it would still remain true that no rights retention at all was necessary in order to deposit all postprints (and attain almost-OA), and that only a publisher endorsement of Green OA self-archiving was needed to attain full OA (1-9*). And it would remain true that re-publication, re-sale and "derivative-works" rights had nothing to do with either OA or the real needs of research and researchers.

[I am not, by the way, dear readers, "adulterating" OA; I am accelerating it, whereas those who are needlessly raising the barriers are (unintentionally) retarding it. Nor do, did or will I ever -- even should the string of B's get still longer! -- accept those parts of the increasingly gilded BBB "definition" of OA that are and ever have been unnecessary or incoherent, hence counterproductive for OA itself -- although I shame-facedly confess to having failed to pick up on that incoherence immediately in B1. That's what comes of being slow-witted. Blackballed from B2, I (with many others) was merely window-dressing at B3, which was really just, by now, ritually reiterating B2. If there is any "permission" barrier at all, it is a psychological one, and it pertains only to the "permission" to provide Green OA, no more -- something I always carefully call "endorse" (or sometimes "bless") rather than "permit" or "allow," because I think that's all just a matter of Wizard of Ozery too, and will be seen to have been such in hindsight, once this maddenly molluscan trek to the optimal and inevitable is at long last behind us...]

One last point -- made in full respect and admiration for Peter Suber. Peter understands every word I am saying and always has. His position, of all the people on this planet, is closest to my own. But Peter in fact has grander goals than I do. His "FOS" (Free Online Scholarship) movement predated OA, and had a much bigger target: It included no less than all of scholarship, online: not just journal articles, but books, multimedia, teaching materials, everything. And the freedom was a greater freedom than freedom to access and use the scholarship.

I greatly value, and fully support Peter's wider goals. But I don't think they are just OA. They are FOS. (I shall be remembered only as an impatient, testy, parochial OA archivangelist, whereas Peter will be rightly recognised as the patient, temperate, ecumenical archangel of FOS.) But OA does have the virtue of being the easier, nearer, surer subgoal.

I think that every time a little divergence arises between Peter and me, it is always a variant of this: He still has his heart and mind set on FOS, and it is good that he does. Someone eventually has to fight that fight too. But OA is narrower than that, and it is also nearer; indeed it is within reach. Hence it is ever so important that we should not over-reach, trying to attain something that is further, and more complicated than OA, when we don't yet even have OA! For we thereby risk needlessly complicating and further delaying the already absurdly overdue attainment of OA.

I think that is what is behind our strategic difference on (1) whether OA requires the elimination of all "permission" barriers or (2) whether, after all, the elimination of all "price" barriers -- via Green OA self-archiving (which is and always has been my model, and my ever-faithful "intuition pump") -- does give us all the capabilities worth having, and worth holding out for. Re-publication rights and the right to create derivative works may be essential for FOS, and for the Creative Commons in general. But they are not essential for OA in particular; and it would be an unnecessary, self-imposed handicap to insist that they should be. That would merely raise barriers for OA where there are and need be none.

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Tuesday, June 12. 2007

Open Access: What Comes With the Territory

Peter Murray-Rust's worries about OA are groundless. Peter worries he can't be be sure that:SUMMARY: Downloading, printing, saving and data-crunching come with the territory if you make your paper freely accessible online (Open Access). You may not, however, create derivative works out of the words of that text. It is the author's own writing, not an audio for remix. And that is as it should be. Its contents (meaning) are yours to data-mine and reuse, with attribution. The words themselves, however, are the author's (apart from attributed fair-use quotes). The frequent misunderstanding that what comes with the OA territory is somehow not enough seems to be based on conflating (1) the text of research articles with (2a) the raw research data on which the text is based, or with (2b) software, or with (2c) multimedia -- all the wrong stuff and irrelevant to OA.

"I can save my own copy (the MIT [site] suggests you cannot print it and may not be allowed to save it)"Pay no attention. Download, print, save and crunch (just as you could have done if you had keyed in the text from reading the pages of a paper book)! [Free Access vs. Open Access (Dec 2003)]

"that it will be available next week"It will. The University OA IRs all see to that. That's why they're making it OA. [Proposed update of BOAI definition of OA: Immediate and Permanent (Mar 2005)]

"that it will be unaltered in the future or that versions will be tracked"Versions are tracked by the IR software, and updated versions are tagged as such. Versions can even be DIFFed.

"that I can create derivative works"You may not create derivative works. We are talking about someone's own writing, not an audio for remix, And that is as it should be. The contents (meaning) are yours to data-mine and reuse, with attribution. The words, however, are the author's (apart from attributed fair-use quotes). Link to them if you need to re-use them verbatim (or ask for permission).

"that I can use machines to text- or data-mine it"Yes, you can. Download and crunch away.

This is all common sense, and all comes with the OA territory when the author makes his full-text freely accessible for all, online. The rest seems to be based on some conflation between (1) the text of research articles and (2a) the raw research data on which the text is based, and with (2b) software, and with (2c) multimedia -- all the wrong stuff and irrelevant to OA).

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Thursday, June 7. 2007

British Classification Society post-RAE Scientometrics

British Classification Society Meeting , "Analysis Methodologies for Post-RAE Scientometrics", Friday 6 July 2007, International Building room IN244 Royal Holloway, University of London, EghamThe selection of appropriate and/or best data analysis methodologies is a result of a number of issues: the overriding goals of course, but also the availability of well formatted, and ease of access to such, data. The meeting will focus on the early stages of the analysis pipeline. An aim of this meeting is to discuss data analysis methodologies in the context of what can be considered as open, objective and universal in a metrics context of scholarly and applied research.

Les Carr and Tim Brody (Intelligence, Agents, Media group, Electronics and Computer Science, University of Southampton): "Open Access Scientometrics and the UK Research Assessment Exercise"Harnad, S. (2007) Open Access Scientometrics and the UK Research Assessment Exercise. In Proceedings of 11th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Scientometrics and Informetrics (in press), Madrid, Spain.

Brody, T., Harnad, S. and Carr, L. (2006) Earlier Web Usage Statistics as Predictors of Later Citation Impact. Journal of the American Association for Information Science and Technology (JASIST) 57(8) pp. 1060-1072.

Carr, L., Hitchcock, S., Oppenheim, C., McDonald, J. W., Champion, T. and Harnad, S. (2006) Extending journal-based research impact assessment to book-based disciplines.

Saturday, May 26. 2007

Craig et al.'s Review of Studies on the OA Citation Advantage

Update Jan 1, 2010: See Gargouri, Y; C Hajjem, V Larivière, Y Gingras, L Carr,T Brody & S Harnad (2010) “Open Access, Whether Self-Selected or Mandated, Increases Citation Impact, Especially for Higher Quality Research”

Update Feb 8, 2010: See also "Open Access: Self-Selected, Mandated & Random; Answers & Questions"

I've read Craig et al.'s critical review concerning the OA citation impact effect and will shortly write a short, mild review. But first here is Sally Morris's posting announcing Craig et al's review, on behalf of the Publishing Research Consortium (which "proposed" the review), followed by a commentary from Bruce Royan on diglib, a few remarks from me, then commentary by JWT Smith on jisc-repositories, followed by my response, and, last, a commentary by Bernd-Christoph Kaemper on SOAF, followed by my response.SUMMARY: The thrust of Craig et al.'s critical review (which was proposed by the Publishing Research Consortium and conducted by the staff of three publishers) is that despite the fact that virtually all studies comparing the citation counts for OA and non-OA articles keep finding the OA citation counts to be higher, it has not been proved beyond a reasonable doubt that the relationship is causal.

I agree: It is merely highly probable, not proved beyond a reasonable doubt. And I also agree that not one of the studies done so far is without some methodological flaw that could be corrected. But it is also highly probable that the results of the methodologically flawless versions of all those studies will be much the same as the results of the current studies. That's what happens when you have a robust major effect, detected by virtually every study, and only ad hoc methodological cavils and special pleading to rebut each of them with. Here is a common sense overview:

(1) Research quality is a necessary, but not a sufficient condition for citation impact: The research must also be accessible to be cited.

(2) Research accessibility is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for citation impact: The research must also be of sufficient quality to be cited.

(3) The OA impact effect is the finding that an article's citation counts are positively correlated with the probability that that article has been made OA: The more an article's citations, the more likely that that article has been made OA.

(4) That correlation has at least three (compatible) causal interpretations:

(4a) OA articles are more likely to be cited.

(4b) More-cited articles are more likely to be made OA.

(4c) A third factor makes it more likely that certain articles will be both more cited and made OA.

(5) Each of these causal interpretations is probably correct, and hence a contributor to the OA impact effect:

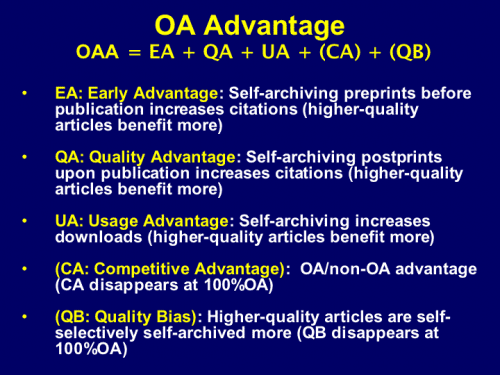

(5a) The better the article, the more likely it is to be cited, hence the more citations it gains if it is made more accessible (4a). (OA Article Quality Advantage, QA)

(5b) The better the article, the more likely it is to be made OA (4b). (OA Article Quality Bias, QB)

(5c) 10% of articles (and authors) receive 90% of citations. The authors of the better articles know they are better, and hence are more likely both to be cited and to make their articles OA, so as to maximize their visibility, accessibility and citations (4c). (OA Author QB and QA)

(6) In addition to QB and QA, there is an OA Early Access effect (EA): providing access earlier increases citations.

(7) The OA citation studies have not yet isolated and estimated the relative sizes of each of these (and other) contributing components. (OA also gives a Download Advantage (DA), and downloads are correlated with later citations; OA articles also have a Competitive Advantage (CA), but CA will vanish -- along with QB -- when all articles are OA).

(8) But the handwriting is on the wall as to the benefits of making articles OA, for those with eyes to see, and no conflicting interests to blind them.

Given all of this, here is a challenge for Craig et al: Instead of striving, like OJ Simpson's Dream Team, only to find flaws in the positive evidence for the OA impact differential, which is equally compatible with either interpretation (OA causes higher citations or higher citations cause OA) why don't Craig et al. do a simple study of their own? Since it is known that (in science) the top 10% of articles published receive 90% of the total citations made, why not test whether and to what extent the top 10% of articles published is over-represented among the c. 15% of articles that are being spontaneously made OA by their authors today? It is, after all, a logical possibility that all or most of the top 10% are already among the 15% that are being made OA: I think it's improbable; but it may repay Craig et al's effort to check whether it is so.

For if it did turn out that all or most of the top-cited 10% of articles are already among the c.15% of articles that are already being made OA, then reaching 100% OA would be far less urgent and important than I have been arguing, and OA mandates would likewise be less important. I for one would no longer find it important enough to archivangelize if I knew it was just for the bottom 90% of articles, the top 10% of articles having already been self-archived, spontaneously and sensibly, by their top 10% authors without having to be mandated. But it is Craig et al. who think this is closer to the truth, not me. So let them go out and demonstrate it.

Sally Morris (Publishing Research Consortium):Craig, Ian; Andrew Plume, Marie McVeigh, James Pringle & Mayur Amin (2007) Do Open Access Articles Have Greater Citation Impact? A critical review of the literature. Journal of Informetrics.A new, comprehensive review of recent bibliometric literature finds decreasing evidence for an effect of 'Open Access' on article citation rates. The review, now accepted for publication in the Journal of Informetrics, was proposed by the Publishing Research Consortium (PRC) and is available at its web site at www.publishingresearch.net. It traces the development of this issue from Steve Lawrence's original study in Nature in 2001 to the most recent work of Henk Moed and others.

Researchers have delved more deeply into such factors as 'selection bias' and 'early view' effects, and began to control more carefully for the effects of disciplinary differences and publication dates. As they have applied these more sophisticated techniques, the relationship between open access and citation, once thought to be almost self-evident, has almost disappeared.

Commenting on the paper, Lord May of Oxford, FRS, past president of the Royal Society, said 'In December 2005, the Royal Society called for an evidence-based approach to the scholarly communications debate. This excellent paper demonstrates that there is actually little evidence of a citation advantage for open access articles.'

The debate will certainly continue, and further studies will continue to refine current work. The PRC welcomes this discussion, and hopes that this latest paper may be a catalyst for a new round of informed scholarly exchange.

Sally Morris on behalf of the Publishing Research Consortium

It is notoriously tricky (at least since David Hume) to "prove" causality empirically. The thrust of the Craig et al. critique is that despite the fact that virtually all studies comparing the citation counts for OA and non-OA articles keep finding the OA citation counts to be higher, it has not been proven beyond a reasonable doubt that the relationship is causal.Bruce Royan wrote on diglib:

Sally claims that according to this article "the relationship between open access and citation, once thought to be almost self-evident, has almost disappeared."

Now I'm no Informetrician, but my reading of the article is that the authors reluctantly acknowledge that Open Access articles do have greater citation impact, but claim that this is less because they are Open Access per se, and more because:-they are available sooner than more conventionally published articles, orSally's point of view is understandable, since she is employed by a consortium of conventional publishers. It's interesting to note that the employers of the authors of this article are Wiley-Blackwell, Thomson Scientific, and Elsevier.

-they tend to be better articles, by more prestigious authors

Even more interesting is that, though this article has been accepted for publication in the conventional "Journal of Informetrics", a pdf of it (described as a summary, but there are 20 pages in JOI format, complete with diagrams, references etc) has already been mounted on the web for free download, in what might be mistaken for an example of green route open access.

Could this possibly be in order to improve the article's impact?

Professor Bruce Royan,

Concurrent Computing Limited.

I agree: It is merely highly probable, not proven beyond a reasonable doubt, that articles are more cited because they are OA, rather than OA merely because they are more cited (or both OA and more cited merely because of a third factor).

And I also agree that not one of the studies done so far is without some methodological flaw that could be corrected.

But it is also highly probable that the results of the methodologically flawless versions of all those studies will be much the same as the results of the current studies. That's what happens when you have a robust major effect, detected by virtually every study, and only ad hoc methodological cavils and special pleading to rebut each of them with.

But I am sure those methodological flaws will not be corrected by these authors, because -- OJ Simpson's "Dream Team" of Defense Attorneys comes to mind -- Craig et al's only interest is evidently in finding flaws and alternative explanations, not in finding out the truth -- if it goes against their client's interests...

Iain D.Craig: Wiley-BlackwellHere is a preview of my rebuttal. It is mostly just common sense, if one has no conflict of interest, hence no reason for special pleading and strained interpretations:

Andrew M.Plume, Mayur Amin: Elsevier

Marie E.McVeigh, James Pringle: Thomson Scientific

(1) Research quality is a necessary, but not a sufficient condition for citation impact: The research must also be accessible to be cited.

(2) Research accessibility is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for citation impact: The research must also be of sufficient quality to be cited.

(3) The OA impact effect is the finding that an article's citation counts are positively correlated with the probability that that article has been made OA: The more an article's citations, the more likely that that article has been made OA.

(4) This correlation has at least three causal interpretations that are not mutually exclusive:

(4a) OA articles are more likely to be cited.(5) Each of these causal interpretations is probably correct, and hence a contributor to the OA impact effect:

(4b) More-cited articles are more likely to be made OA.

(4c) A third factor makes it more likely that certain articles will be both more cited and made OA.

(5a) The better the article, the more likely it is to be cited, hence the more citations it gains if it is made more accessible (4a). (OA Article Quality Advantage, QA)(6) In addition to QB and QA, there is an OA Early Access effect (EA): providing access earlier increases citations.

(5b) The better the article, the more likely it is to be made OA (4b). (OA Article Quality Bias, QB)

(5c) 10% of articles (and authors) receive 90% of citations. The authors of the better articles know they are better, and hence are more likely both to be cited and to make their articles OA, so as to maximize their visibility, accessibility and citations (4c). (OA Author QB and QA)

(7) The OA citation studies have not yet isolated and estimated the relative sizes of each of these (and other) contributing components. (OA also gives a Download Advantage (DA), and downloads are correlated with later citations; OA articles also have a Competitive Advantage (CA), but CA will vanish -- along with QB -- when all articles are OA).

(8) But the handwriting is on the wall as to the benefits of making articles OA, for those with eyes to see, and no conflicting interests to blind them.

I do agree completely, however, with erstwhile (Princetonian and) Royal Society President Bob May's slightly belated call for "an evidence-based approach to the scholarly communications debate."

John Smith (JS) wrote in jisc-repositories:

I wonder if we can come at this discussion concerning the impact of OA on citation counts from another angle? Assuming we have a traditional academic article of interest to only a few specialists there is a simple upper bound to the number of citations it will have no matter how accessible it is.That is certainly true. It is also true that 10% of articles receive 90% of the citations. OA will not change that ratio, it will simply allow the usage and citations of those articles that were not used and cited because they could not be accessed to rise to what they would have been if they could have been used and cited.

JS: Also, the majority of specialist academics work in educational institutions where they have access to a wide range of paid for sources for their subject.OA is not for those articles and those users that already have paid access; it is for those that do not. No institution can afford paid access to all or most of the 2.5 million articles published yearly in the world's 24,000 peer-reviewed journals, and most institutions can only afford access to a small fraction of them.

OA is hence for that large fraction (the complement of the small fraction) of those articles that most users and most institutions cannot access. The 10% of that fraction that merit 90% of the citations today will benefit from OA the most, and in proportion to their merit. That increase in citations also corresponds to an increase in scholarly and scientific productivity and progress for everyone.

JS: Therefore any additional citations must mainly come from academics in smaller institutions that do not provide access to all relevant titles for their subject and/or institutions in the poorer countries of the world.It is correct that the additional citations will come from academics at the institutions that cannot afford paid access to the journals in which the cited articles appeared. It might be the case that the access denial is concentrated in the smaller institutions and the poorer countries, but no one knows to what extent that is true, and one can also ask whether it is relevant. For the OA problem is not just an access problem but an impact problem. And the research output of even the richest institutions is losing a large fraction of its potential research impact because it is inaccessible to the fraction to whom it is inaccessible, whether or not that missing fraction is mainly from the smaller, poorer institutions.

JS: Should it not be possible therefore to examine the citers to these OA articles where increased citation is claimed and show they include academics in smaller institutions or from poorer parts of the world?Yes, it is possible, and it would be a good idea to test the demography of access denial and OA impact gain. But, again, one wonders: Why would one assign this question of demographic detail a high priority at this time, when the access and impact loss have already been shown to be highly probable, when the remedy (mandated OA self-archiving) is at hand and already overdue, and when most of the skepticism about the details of the OA impact advantage comes from those who have a vested interest in delaying or deterring OA self-archiving mandates from being adopted?

(It is also true that a portion of the OA impact advantage is a competitive advantage that will disappear once all articles are OA. Again, one is inclined to reply: So what?)

This is not just an academic exercise but a call to action to remedy a remediable practical problem afflicting research and researchers.

JS: However, even if this were done and positive results found there is still another possible explanation. Items published in both paid for and free form are indexed in additional indexing services including free services like OAIster and CiteSeer. So it may be that it is not the availability per se that increases citation but the findability? Those who would have had access anyway have an improved chance of finding the article. Do we have proof that the additional citers accessed the OA version (assuming there is both an OA and paid for version)?Increased visibility and improved searching are always welcome, but that is not the OA problem. OAIster's usefulness is limited by the fact that it only contains the c. 15% of the literature that is being self-archived spontaneously (i.e., unmandated) today. Citeseer is a better niche search engine because computer scientists self-archive a much higher proportion of their research. But the obvious benchmark today is Google Scholar, which is increasingly covering all cited articles, whether OA or non-OA. It is in vain that Google Scholar enhances the visibility of non-OA articles for those would-be users to whom they are not accessible. Those users could already have accessed the metadata of those articles from online indices such as Web of Science or PubMed, only to reach a toll-access barrier when it came to accessing the inaccessible full-text corresponding to the visible metadata.

JS: It is possible that my queries above have already been answered. If so a reference to the work will suffice as a response.Accessibility is a necessary (but not a sufficient) condition for usage and impact. There is no risk that maximising accessibility will fail to maximise usage and impact. The only barrier between us and 100% OA is a few keystrokes.

I am a supporter of OA but also concerned that it is not falsely praised. If it is praised for some advantage and that advantage turns out not to be there it will weaken the position of OA proponents.

It is appalling that we continue to dither about this; it is analogous to dithering about putting on (or requiring) seat-belts until we have made sure that the beneficiaries are not just the small and the poor, and that seat-belts do not simply make drivers more safety-conscious.

JS: Even if the apparent citation advantage of OA turns out to be false it does not weaken the real advantages of OA. We should not be drawn into a time and effort wasting defence of it while there is other work to be done to promote OA.The real advantage of Open Access is Access. The advantage of Access is Usage and Impact (of which citations are one indicator). The Craig et al. study has not shown that the OA Impact Advantage is not real. It has simply pointed out that correlation does not entail causation. Duly noted. I agree that no time or effort should be spent now trying to demonstrate causation. The time and effort should be used to provide OA.

Bernd-Christoph Kaemper (B-CK) wrote on SOAF:I couldn't quite follow the logic of this posting. It seemed to be saying that, yes, there is evidence that OA increases impact, it is even trivially obvious, but, no, we cannot estimate how much, because there are possible confounding factors and the size of the increase varies.

Elsevier said that citation rates of their journals had gone up considerably because of the increased access through wide- spread online availability of their journals...

Online availability clearly increased the IF [journal citation impact factor]. In the FUTON subcategory, there was an IF gradient favoring journals with freely available articles. ..."

I think it is quite obvious why sources available with open access will be used and cited more often than others...

So the usefulness of open access is a matter of daily experience, not so much of academic discussions whether there is any empirical proof for a citation advantage of open access that may be isolated by eliminating all possible confounders...

That open access leads to more visibility and thereby potentially more citations is trivial, but this relative open access advantage will vary from journal to journal...

Due to the multitude of possible confounding factors I would not believe any of the figures calculated by Stevan Harnad as the cumulated lost impact, or conversely, the possible gain.

All studies have found that the size of the OA impact differential varies from field to field, journal to journal, and year to year. The range of variation is from +25% to over +250% percent. But the differential is always positive, and mostly quite sizeable. That is why I chose a conservative overall estimate of +50% for the potential gain in impact if it were not just the current 15% of research that was being made OA, but also the remaining 85%. (If you think 50% is not conservative enough, use the lower-bound 25%: You'll still find a substantial potential impact gain/loss. If you think self-selection accounts for half the gain, split it in half again: there's still plenty of gain, once you multiply by 85% of total citations.)

An interesting question that has since arisen (and could be answered by similar studies) is this:

It is a logical possibility that all or most of the top 10% are already among the 15% that are being made OA: I rather doubt it; but it would be worth checking whether it is so. [Attention lobbyists against OA mandates! Get out your scissors here and prepare to snip an out-of-context quote...]Since it is known that (in science) the top 10% of articles published receive 90% of the total citations made (Seglen 1992), to what extent is the top 10% of articles published over-represented among the c. 15% of articles that are being spontaneously made OA by their authors today?

[snip]The empirical studies of the relation between OA and impact have been mostly motivated by the objective of accelerating the growth of OA -- and thereby the growth of research usage and impact. Those who are oersuaded that the OA impact differential is merely or largely a non-causal self-selection bias are encouraged to demonstrate that that is the case.

If it did turn out that all or most of the top-cited 10% of articles are already among the c.15% of articles that are already being made OA, then reaching 100% OA would be far less urgent and important than I had argued, and OA mandates would likewise be less important. I for one would no longer find it important enough to archivangelize if I knew it was just for the bottom 90% of articles, the top 10% of articles having already been self-archived, spontaneously and sensibly, by their top 10% authors without having to be mandated.

[/snip]

Note very carefully, though, that the observed correlation between OA and citations takes the form of a correlation between the number of OA articles, relative to non-OA articles, at each citation level. The more highly cited an article, the more likely it is OA. This is true within journals, and within and across years, in every field tested.

And this correlation can arise because more-cited articles are more likely to be made OA or because articles that are made OA are more likely to be cited (or both -- which is what I think is in reality the case). It is certainly not the case that self-selection is the default or null hypothesis, and that those who interpret the effect as OA causing the citation increase hence have the burden of proof: The situation is completely symmetric numerically; so your choice between the two hypotheses is not based on the numbers, but on other considerations, such as prima facie plausibility -- or financial interest.

Until and unless it is shown empirically that today's OA 15% already contains all or most of the top-cited 10% (and hence 90% of what researchers cite), I think it is a much more plausible interpretation of the existing findings that OA is a cause of the increased usage and citations, rather than just a side-effect of them, and hence that there is usage and impact to be gained by providing and mandating OA. (I can quite understand why those who have a financial interest in its being otherwise [Craig et al. 2007] might prefer the other interpretation, but clearly prima facie plausibility cannot be their justification.)

I also think that 50% of total citations is a plausible overall estimate of the potential gain from OA, as long as it is understood clearly that that the 50% gain does not apply to every article made OA. Many articles are not found useful enough to cite no matter how accessible you make them. The 50% citation gain will mostly accrue to the top 10% of articles, as citations always do (though OA will no doubt also help to remedy some inequities and will sometimes help some neglected gems to be discovered and used more widely). In other words, the OA advantage to an article will be roughly proportional to that article's intrinsic citation value (independent of OA).

Other interesting questions: The top-cited articles are not evenly distributed among journals. The top journals tend to get the top-cited articles. It is also unlikely that journal subscriptions are evenly distributed among journals: The top journals are likely to be subscribed to more, and are hence more accessible.

So if someone is truly interested in these questions (as I am not!), they might calculate a "toll-accessibility index" (TAI) for each article, based on the number of researchers/institutions that have toll access to the journal in which that article is published. An analysis of covariance can then be done to see whether and how much the OA citation advantage is reduced if one controls for the article's TAI. (I suspect the answer will be: somewhat, but not much.)

B-CK: Could we do a thought experiment? From a representative group of authors, choose a sample of authors randomly and induce them to make their next article open access. Do you believe they will see as much gain in citations compared to their previous average citation levels as predicted from the various current "OA advantage" studies where several confounding factors are operating? Probably not - but what would remain of that advantage? -- I find that difficult to predict or model.From a random sample, I would expect an increase of around 50% or more in total citations, 90% of the increased citations going to the top 10%, as always.

B-CK: As I learned from your posting, you seem to predict that it will anyway depend on the previous citedness of the members of that group (if we take that as a proxy for the unknown actual intrinsic citation value of those articles), in the sense that more-cited authors will see a larger percentage increase effect.I don't think it's just a Matthew Effect; I think the highest quality papers get the most citations (90%), and the highest quality papers are apparently about 10% (in science, according to Seglen).

B-CK: To turn your argument around, most authors happily going open access in expectation of increased citation might be disappointed because the 50% increase will only apply to a small minority of them.That's true; but you could say the same for most authors going into research at all. There is no guarantee that they will produce the highest quality research, but I assume that researchers do what they do in the hope that they will, if not this time, then the next time, produce the highest quality research.

B-CK: That was the reason why I said that (as an individual author) I would rather not believe in any "promised" values for the possible gain.Where there is life, and effort, there is hope. I think every researcher should do research, and publish, and self-archive, with the ambition of doing the best quality work, and having it rewarded with valuable findings, which will be used and cited.

My "promise", by the way, was never that each individual author would get 50% more citations. (That would actually have been absurd, since over 50% of papers get no citations at all -- apart from self-citation -- and 50% of 0 is still 0.)

My promise, in calculating the impact gain/loss that you doubted, was to countries, research funders and institutions. On the assumption that the research output of each roughly covers the quality spectrum, they can expect their total citations to increase by 50% or more with OA, but that increase will be mostly at their high-quality end. (And the total increase is actually about 85% of 50%, as the baseline spontaneous self-archiving rate is about 15%.)

B-CK: That doesn't mean though that there are not enough other reasons to go for open access (I mentioned many of them in my posting).There are other reasons, but researchers' main motivation for conducting and publishing research is in order to make a contribution to knowledge that will be found useful by, and used by, and built upon by other researchers. There are pedagogic goals too, but I think they are secondary, and I certainly don't think they are strong enough to induce a researcher to make his publications OA, if the primary reason was not reason enough to induce them.

(Actually, I don't think any of the reasons are enough to induce enough researchers to provide OA, and that's why Green OA mandates are needed -- and being provided -- by researchers' institutions and funders.)

B-CK: With respect to the toll accessibility index, I completely agree. The occasional good article in an otherwise "obscure" journal probably has a lot to gain from open access, as many people would not bother to try to get hold of a copy should they find it among a lot of others in a bibliographic database search, if it doesn't look from the beginning like a "perfect match" of what they are looking for.You agree with the toll-accessibility argument prematurely: There are as yet no data on it, whereas there are plenty of data on the correlation between OA and impact.

B-CK: An interesting question to look at would also be the effect of open access on non-formal citation modes like web linking, especially social bookmarking. Clearly NPG is interested in Connotea also as a means to enhance the visibility of articles in their own toll access articles. Has anyone already tried such investigations?Although I cannot say how much it is due to other kinds of links or from citation links themselves, the University of Southampton, the first institution with a (departmental) Green OA self-archiving mandate, and also the one with the longest-standing mandate also has a surprisingly high webmetric, university-metric and G-factor rank:

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Bollen, J., Van de Sompel, H., Smith, J. and Luce, R. (2005) Toward alternative metrics of journal impact: A comparison of download and citation data. Information Processing and Management, 41(6): 1419-1440.

Brody, T., Harnad, S. and Carr, L. (2006) Earlier Web Usage Statistics as Predictors of Later Citation Impact. Journal of the American Association for Information Science and Technology (JASIST) 57(8) pp. 1060-1072.

Craig, Ian; Andrew Plume, Marie McVeigh, James Pringle & Mayur Amin (2007) Do Open Access Articles Have Greater Citation Impact? A critical review of the literature. Journal of Informetrics.

Davis, P. M. and Fromerth, M. J. (2007) Does the arXiv lead to higher citations and reduced publisher downloads for mathematics articles? Scientometrics 71: 203-215.

See critiques: 1 and 2.

Diamond, Jr. , A. M. (1986) What is a Citation Worth? Journal of Human Resources 21:200-15, 1986,

Eysenbach, G. (2006) Citation Advantage of Open Access Articles. PLoS Biology 4: 157.

Hajjem, C., Harnad, S. and Gingras, Y. (2005) Ten-Year Cross-Disciplinary Comparison of the Growth of Open Access and How it Increases Research Citation Impact. IEEE Data Engineering Bulletin 28(4) pp. 39-47.

Hajjem, C. and Harnad, S. (2006) Manual Evaluation of Robot Performance in Identifying Open Access Articles. Technical Report, Institut des sciences cognitives, Universite du Quebec a Montreal.

Hajjem, C. and Harnad, S. (2006) The Self-Archiving Impact Advantage: Quality Advantage or Quality Bias? Technical Report, ECS, University of Southampton.

Hajjem, C. and Harnad, S. (2007) Citation Advantage For OA Self-Archiving Is Independent of Journal Impact Factor, Article Age, and Number of Co-Authors. Technical Report, Electronics and Computer Science, University of Southampton.

Hajjem, C. and Harnad, S. (2007) The Open Access Citation Advantage: Quality Advantage Or Quality Bias? Technical Report, Electronics and Computer Science, University of Southampton.

Harnad, S. & Brody, T. (2004) Comparing the Impact of Open Access (OA) vs. Non-OA Articles in the Same Journals, D-Lib Magazine 10 (6) June

Harnad, S. (2005) Making the case for web-based self-archiving. Research Money 19(16).

Harnad, S. (2005) Maximising the Return on UK's Public Investment in Research. (Unpublished ms.)

Harnad, S. (2005) OA Impact Advantage = EA + (AA) + (QB) + QA + (CA) + UA. (Unpublished ms.)

Harnad, S. (2005) On Maximizing Journal Article Access, Usage and Impact. Haworth Press (occasional column).

Harnad, S. (2006) Within-Journal Demonstrations of the Open-Access Impact Advantage: PLoS, Pipe-Dreams and Peccadillos (LETTER). PLOS Biology 4(5).

Henneken, E. A., Kurtz, M. J., Eichhorn, G., Accomazzi, A., Grant, C., Thompson, D., and Murray, S. S. (2006) Effect of E-printing on Citation Rates in Astronomy and Physics. Journal of Electronic Publishing, Vol. 9, No. 2, Summer 2006

Henneken, E. A., Kurtz, M. J., Warner, S., Ginsparg, P., Eichhorn, G., Accomazzi, A., Grant, C. S., Thompson, D., Bohlen, E. and Murray, S. S. (2006) E-prints and Journal Articles in Astronomy: a Productive Co-existence Learned Publishing.

Kurtz, M. J., Eichhorn, G., Accomazzi, A., Grant, C. S., Demleitner, M., Murray, S. S. (2005) The Effect of Use and Access on Citations. Information Processing and Management, 41 (6): 1395-1402.

Kurtz, Michael and Brody, Tim (2006) The impact loss to authors and research. In, Jacobs, Neil (ed.) Open Access: Key strategic, technical and economic aspects. Oxford, UK, Chandos Publishing.

Lawrence, S, (2001) Online or Invisible?, Nature 411 (2001) (6837): 521.

Metcalfe, Travis S (2006) The Citation Impact of Digital Preprint Archives for Solar Physics Papers. Solar Physics 239: 549-553

Moed, H. F. (2006) The effect of 'Open Access' upon citation impact: An analysis of ArXiv's Condensed Matter Section (preprint)

Perneger, T. V. (2004) Relation between online 'hit counts' and subsequent citations: prospective study of research papers in the British Medical Journal. British Medical Journal 329:546-547.

Seglen, P.O. (1992) The skewness of science. The American Society for Information Science 43: 628-638

Tuesday, May 1. 2007

OA Citation Impact Study: No Conclusions Possible

Update Jan 1, 2010: See Gargouri, Y; C Hajjem, V Larivière, Y Gingras, L Carr,T Brody & S Harnad (2010) “Open Access, Whether Self-Selected or Mandated, Increases Citation Impact, Especially for Higher Quality Research”

Update Feb 8, 2010: See also "Open Access: Self-Selected, Mandated & Random; Answers & Questions"

Tonta, Yaşar and Ünal, Yurdagül and Al, Umut (2007) The Research Impact of Open Access Journal Articles. In Proceedings ELPUB 2007, the 11th International Conference on Electronic Publishing, Focusing on challenges for the digital spectrum, pp. 1-11, Vienna (Austria).The above article compared average citation counts in several different fields for a sample of articles in a sample of OA journals in the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ).

The average citation counts for articles in the OA journals were found to vary across fields. It was concluded that OA research impact varies across fields.

No comparison was made with non-OA journals in the same fields. Hence it is impossible to say whether any of these differences have anything to do with OA. Fields no doubt differ in their average number of citations. Journals no doubt differ too, in subject matter, quality, and citation impact, hence must be equated: It is not clear whether the OA journals in each field are the top, medium or bottom journals, relative to the non-OA journals.

No conclusions at all can be drawn from this study. The authors are encouraged to do the necessary controls.

Note also that Hajjem et al. 2005 (and others) report that the ratio of OA/non-OA articles is positively correlated with citation counts. This can mean that higher-quality articles are more likely to be made OA (Quality Bias), or that the OA impact advantage is greater for higher-quality articles (Quality Advantage) -- or, most likely, both (Hajjem & Harnad 2006).

Hajjem, C., Harnad, S. and Gingras, Y. (2005) Ten-Year Cross-Disciplinary Comparison of the Growth of Open Access and How it Increases Research Citation Impact. IEEE Data Engineering Bulletin 28(4) pp. 39-47.

Hajjem, C. and Harnad, S. (2006) The Open Access Impact Advantage: Quality Advantage or Quality Bias? Technical Report, ECS, University of Southampton.

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Sunday, January 21. 2007

The Open Access Citation Advantage: Quality Advantage Or Quality Bias?

Update Jan 1, 2010: See Gargouri, Y; C Hajjem, V Larivière, Y Gingras, L Carr,T Brody & S Harnad (2010) “Open Access, Whether Self-Selected or Mandated, Increases Citation Impact, Especially for Higher Quality Research”

Update Feb 8, 2010: See also "Open Access: Self-Selected, Mandated & Random; Answers & Questions"

This is a preview of some preliminary data (not yet refereed), collected by my doctoral student at UQaM, Chawki Hajjem. This study was done in part by way of response to Henk Moed's replies to my comments on Moed's (self-archived) preprint:

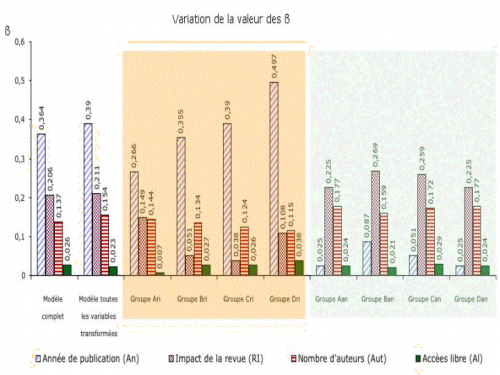

SUMMARY: Many studies have now reported the positive correlation between Open Access (OA) self-archiving and citation counts ("OA Advantage," OAA). But does this OAA occur because articles that are self-archived are more likely to be cited ("Quality Advantage": QA) or because articles that are more likely to be cited are more likely to be self-archived ("Quality Bias," QB)? The probable answer is both. Three studies [by Kurtz and co-workers in astrophysics, Moed in condensed matter physics, and Davis & Fromerth in mathematics] had attributed the OAA to QB [and to EA, the Early Advantage of self-archiving the preprint before publication] rather than QA. These three fields, however, happen to be among the minority of fields that (1) make heavy use of prepublication preprints and (2) have less of a postprint access problem than most other fields. Chawki Hajjem has now analyzed preliminary evidence based on over 100,000 articles from multiple fields, comparing self-selected self-archiving with mandated self-archiving to estimate the contributions of QB and QA to the OAA. Both factors contribute, and the contribution of QA is greater.

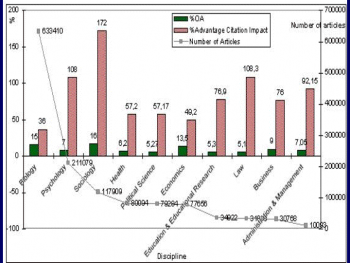

Moed, H. F. (2006) The effect of 'Open Access' upon citation impact: An analysis of ArXiv's Condensed Matter SectionMoed's study is about the "Open Access Advantage" (OAA) -- the higher citation counts of self-archived articles -- observable across disciplines as well as across years as in the following graphs from Hajjem et al. 2005 (red bars are the OAA):

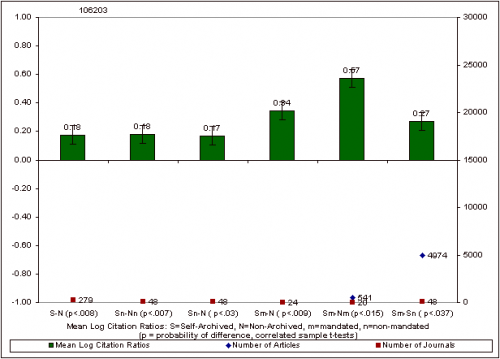

The focus of the present discussion is the factors underlying the OAA. There are at least five potential contributing factors, but only three of them are under consideration here: (1) Early Advantage (EA), (2) Quality Advantage (QA) and (3) Quality Bias (QB -- also called "Self-Selection Bias").FIGURE 1. Open Access Citation Advantage By Discipline and By Year.

Green bars are percentage of articles self-archived (%OA); red bars, percentage citation advantage (%OAA) for self-archived articles for 10 disciplines (upper chart) across 12 years (lower chart, 1992-2003). Gray curve indicates total articles by discipline and year.

Source: Hajjem, C., Harnad, S. and Gingras, Y. (2005) Ten-Year Cross-Disciplinary Comparison of the Growth of Open Access and How it Increases Research Citation Impact. IEEE Data Engineering Bulletin 28(4) pp. 39-47.

Preprints that are self-archived before publication have an Early Advantage (EA): they get read, used and cited earlier. This is uncontested.

Kurtz, Michael and Brody, Tim (2006) The impact loss to authors and research. In, Jacobs, Neil (ed.) Open Access: Key strategic, technical and economic aspects. Oxford, UK, Chandos Publishing.In addition, the proportion of articles self-archived at or after publication is higher in the higher "citation brackets": the more highly cited articles are also more likely to be the self-archived articles.

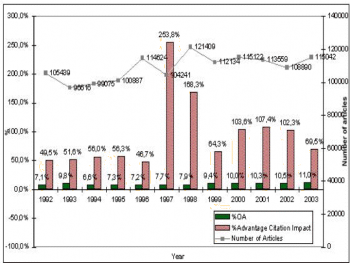

The question, then, is about causality: Are self-archived articles more likely to be cited because they are self-archived (QA)? Or are articles more likely to be self-archived because they are more likely to be cited (QB)?FIGURE 2. Correlation between Citedness and Ratio of Open Access (OA) to Non-Open Access (NOA) Ratios.

The (OAc/TotalOAc)/(NOAc/TotalNOAc) ratio (across all disciplines and years) increases as citation count (c) increases (r = .98, N=6, p<.005). The more cited an article, the more likely that it is OA. (Hajjem et al. 2005)

The most likely answer is that both factors, QA and QB, contribute to the OAA: the higher quality papers gain more from being made more accessible (QA: indeed the top 10% of articles tend to get 90% of the citations). But the higher quality papers are also more likely to be self-archived (QB).

As we will see, however, the evidence to date, because it has been based exclusively on self-selected (voluntary) self-archiving, is equally compatible with (i) an exclusive QA interpretation, (ii) an exclusive QB interpretation or (iii) the joint explanation that is probably the correct one.

The only way to estimate the independent contributions of QA and QB is to compare the OAA for self-selected (voluntary) self-archiving with the OAA for imposed (obligatory) self-archiving. We report some preliminary results for this comparison here, based on the (still small sample of) Institutional Repositories that already have self-archiving mandates (chiefly CERN, U. Southampton, QUT, U. Minho, and U. Tasmania).

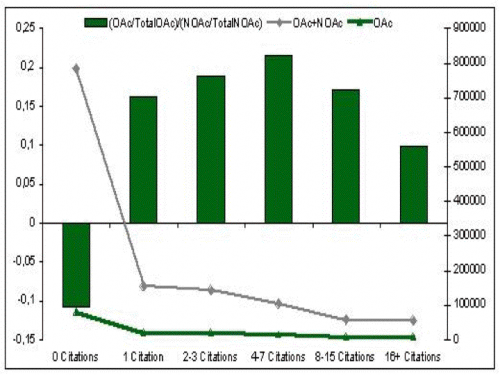

FIGURE 3. Self-Selected Self-Archiving vs. Mandated Self-Archiving: Within-Journal Citation Ratios (for 2004, all fields).

S = citation counts for articles self-archived at institutions with (Sm) and without (Sn) a self-archiving mandate. N = citation counts for non-archived articles at institutions with (Nm) and without (Nn) mandate (i.e., Nm = articles not yet compliant with mandate). Grand average of (log) S/N ratios (106,203 articles; 279 journals) is the OA advantage (18%); this is about the same as for Sn/Nn (27972 articles, 48 journals, 18%) and Sn/N (17%); ratio is higher for Sm/N (34%), higher still for Sm/Nm (57%, 541 articles, 20 journals); and Sm/Sn = 27%, so self-selected self-archiving does not yield more citations than mandated; rather the reverse. (All six within-pair differences are significant: correlated sample t-tests.) (NB: preliminary, unrefereed results.)

Summary: These preliminary results suggest that both QA and QB contribute to OAA, and that the contribution of QA is greater than that of QB.

Discussion: On Fri, 8 Dec 2006, Henk Moed [HM] wrote:

HM: "Below follow some replies to your comments on my preprint 'The effect of 'Open Access' upon citation impact: An analysis of ArXiv's Condensed Matter Section'...The findings are definitely consistent for Astronomy and for Condensed Matter Physics. In both cases, most of the observed OAA came from the self-archiving of preprints before publication (EA).

"1. Early view effect. [EA] In my case study on 6 journals in the field of condensed matter physics, I concluded that the observed differences between the citation age distributions of deposited and non-deposited ArXiv papers can to a large extent - though not fully - be explained by the publication delay of about six months of non-deposited articles compared to papers deposited in ArXiv. This outcome provides evidence for an early view [EA] effect upon citation impact rates, and consequently upon ArXiv citation impact differentials (CID, my term) or Arxiv Advantage (AA, your term)."SH: "The basic question is this: Once the AA (Arxiv Advantage) has been adjusted for the "head-start" component of the EA (by comparing articles of equal age -- the age of Arxived articles being based on the date of deposit of the preprint rather than the date of publication of the postprint), how big is that adjusted AA, at each article age? For that is the AA without any head-start. Kurtz never thought the EA component was merely a head start, however, for the AA persists and keeps growing, and is present in cumulative citation counts for articles at every age since Arxiving began".HM: "Figure 2 in the interesting paper by Kurtz et al. (IPM, v. 41, p. 1395-1402, 2005) does indeed show an increase in the very short term average citation impact (my terminology; citations were counted during the first 5 months after publication date) of papers as a function of their publication date as from 1996. My interpretation of this figure is that it clearly shows that the principal component of the early view effect is the head-start: it reveals that the share of astronomy papers deposited in ArXiv (and other preprint servers) increased over time. More and more papers became available at the date of their submission to a journal, rather than on their formal publication date. I therefore conclude that their findings for astronomy are fully consistent with my outcomes for journals in the field of condensed matter physics."

Moreover, in Astronomy there is already 100% "OA" to all articles after publication, and this has been the case for years now (for the reasons Michael Kurtz and Peter Boyce have pointed out: all research-active astronomers have licensed access as well as free ADS access to all of the closed circle of core Astronomy journals: otherwise they simply cannot be research-active). This means that there is only room for EA in Astronomy's OAA. And that means that in Astronomy all the questions about QA vs QB (self-selection bias) apply only to the self-archiving of prepublication preprints, not to postpublication postprints, which are all effectively "OA."

To a lesser extent, something similar is true in Condensed-Matter Physics (CondMP): In general, research-active physicists have better access to their required journals via online licensing than other fields do (though one does wonder about the "non-research-active" physicists, and what they could/would do if they too had OA!). And CondMP too is a preprint self-archiving field, with most of the OAA differential again concentrated on the prepublication preprints (EA). Moreover, Moed's test for whether or not a paper was self-archived was based entirely on its presence/absence in ArXiv (as opposed to elsewhere on the Web, e.g., on the author's website or in the author's Institutional Repository).

Hence Astronomy and CondMP are fields that are "biassed" toward EA effects. It is not surprising, therefore, that the lion's share of the OAA turns out to be EA in these fields. It also means that the remaining variance available for testing QA vs. QB in these fields is much narrower than in fields that do not self-archive preprints only, or mostly.

Hence there is no disagreement (or surprise) about the fact that most of the OAA in Astronomy and CondMP is due to EA. (Less so in the slower-moving field of maths; see: "Early Citation Advantage?.")

I agree with all this: The probable quality of the article was estimated from the probable quality of the author, based on citations for non-OA articles. Now, although this correlation, too, goes both ways (are authors' non-OA articles more cited because their authors self-archive more or do they self-archive more because they are more cited?), I do agree that the correlation between self-archiving-counts and citation-counts for non-self-archived articles by the same author is more likely to be a QB effect. The question then, of course, is: What proportion of the OAA does this component account for?SH: "The fact that highly-cited articles (Kurtz) and articles by highly-cited authors (Moed) are more likely to be Arxived certainly does not settle the question of cause and effect: It is just as likely that better articles benefit more from Arxiving (QA) as that better authors/articles tend to Arxive/be-Arxived more (QB)."HM: "2. Quality bias. I am fully aware that in this research context one cannot assess whether authors publish [sic] their better papers in the ArXiv merely on the basis of comparing citation rates of archived and non-archived papers, and I mention this in my paper. Citation rates may be influenced both by the 'quality' of the papers and by the access modality (deposited versus non-deposited). This is why I estimated author prominence on the basis of the citation impact of their non-archived articles only. But even then I found evidence that prominent, influential authors (in the above sense) are overrepresented in papers deposited in ArXiv."

HM: "But I did more that that. I calculated Arxiv Citation Impact Differentials (CID, my term, or ArXiv Advantage, AA, your term) at the level of individual authors. Next, I calculated the median CID over authors publishing in a journal. How then do you explain my empirical finding that for some authors the citation impact differential (CID) or ArXiv Advantage is positive, for others it is negative, while the median CID over authors does not significantly differ from zero (according to a Sign test) for all journals studied in detail except Physical Review B, for which it is only 5 per cent? If there is a genuine 'OA advantage' at stake, why then does it for instance not lead to a significantly positive median CID over authors? Therefore, my conclusion is that, controlling for quality bias and early view effect, in the sample of 6 journals analysed in detail in my study, there is no sign of a general 'open access advantage' of papers deposited in ArXiv's Condensed Matter Section."My interpretation is that EA is the largest contributor to the OAA in this preprint-intensive field (i.e., most of the OAA comes from the prepublication component) and that there is considerable variability in the size of the (small) residual (non-EA) OAA. For a small sample, at the individual journal level, there is not enough variance left for a significant OAA, once one removes the QB component too. Perhaps this is all that Henk Moed wished to imply. But the bigger question for OA concerns all fields, not just those few that are preprint-intensive and that are relatively well-heeled for access to the published version. Indeed, the fundamental OA and OAA questions concern the postprint (not the preprint) and the many disciplines that do have access problems, not the happy few that do not!

The way to test the presence and size of both QB and QA in these non-EA fields is to impose the OA, preferably randomly, on half the sample, and then compare the size of the OAA for imposed ("mandated") self-archiving (Sm) with the size of the OAA for self-selected ("nonmandated") self-archiving (Sn), in particular by comparing their respective ratios to non-self-archived articles in the same journal and year: Sm/N vs. Sn/N).

If Sn/N > Sm/N then QB > QA, and vice versa. If Sn/N = 1, then QB is 0. And if Sm/N = 1 then QA is 0.

It is a first approximation to this comparison that has just been done (FIGURE 3) by my doctoral student, Chawki Hajjem, across fields, for self-archived articles in five Institutional Repositories (IRs) that have OA self-archiving mandates, for 106,203 articles published in 276 biomedical journal 2004, above.

The mandates are still very young and few, hence the sample is still small; and there are many potential artifacts, including selective noncompliance with the mandate as well as disciplinary bias. But the preliminary results so far suggest that (1) QA is indeed > 0, and (2) QA > QB.

[I am sure that we will now have a second round from die-hards who will want to argue for a selective-compliance effect, as a 2nd-order last gasp for the QB-only hypothesis, but of course that loses all credibility as IRs approach 100% compliance: We are analyzing our mandated IRs separately now, to see whether we can detect any trends correlated with an IR's %OA. But (except for the die-hards, who will never die), I think even this early sample already shows that the OA advantage is unlikely to be only or mostly a QB effect.]

HM: "3. Productive versus less productive authors. My analysis of differences in Citation Impact differentials between productive and less productive authors may seem "a little complicated". My point is that if one selects from a set of papers deposited in ArXiv a paper authored by a junior (or less productive) scientist, the probability that this paper is co-authored by a senior (or more productive) author is higher than it is for a paper authored by a junior scientist but not deposited in ArXiv. Next, I found that papers co-authored by both productive and less productive authors tend to have a higher citation impact than articles authored solely by less productive authors, regardless of whether these papers were deposited in ArXiv or not. These outcomes lead me to the conclusion that the observed higher CID for less productive authors compared to that of productive authors can be interpreted as a quality bias."It still sounds a bit complicated, but I think what you mean is that (1) mixed multi-author papers (ML, with M = More productive authors, L = less productive authors) are more likely to be cited than unmixed multi-author (LL) papers with the same number of authors, and that (2) such ML papers are also more likely to be self-archived. (Presumably MM papers are the most cited and most self-archived of multi-author papers.)

That still sounds to me like a variant on the citation/self-archiving correlation, and hence intepretable as either QA or QB or both. (Chawki Hajjem has also found that citation counts are positively correlated with the number of authors an article has: this could either be a self-citation bias or evidence that multi-authored paper tend to be better ones.)