Monday, November 20. 2006

The Self-Archiving Impact Advantage: Quality Advantage or Quality Bias?

Update Jan 1, 2010: See Gargouri, Y; C Hajjem, V Larivière, Y Gingras, L Carr,T Brody & S Harnad (2010) “Open Access, Whether Self-Selected or Mandated, Increases Citation Impact, Especially for Higher Quality Research”

Update Feb 8, 2010: See also "Open Access: Self-Selected, Mandated & Random; Answers & Questions"

Michael Kurtz's papers have confirmed that in astronomy/astrophysics (astro), articles that have been self-archived -- let's call this "Arxived" to mark it as the special case of depositing in the central Physics Arxiv -- are cited (and downloaded) twice as much as non-Arxived articles. Let's call this the "Arxiv Advantage" (AA).

SUMMARY: In astrophysics, Kurtz found that articles that were self-archived by their authors in Arxiv were downloaded and cited twice as much as those that were not. He traced this enhanced citation impact to two factors: (1) Early Access (EA): The self-archived preprint was accessible earlier than the publisher's version (which is accessible to all research-active astrophysicists as soon as it is published, thanks to Kurtz's ADS system). (Hajjem, however, found that in other fields, which self-archive only published postprints and do have accessibility/affordability problems with the publisher's version, self-archived articles still have enhanced citation impact.) Kurtz's second factor was: (2) Quality Bias (QB), a selective tendency for higher quality articles to be preferentially self-archived by their authors, as inferred from the fact that the proportion of self-archived articles turns out to be higher among the more highly cited articles. (The very same finding is of course equally interpretable as (3) Quality Advantage (QA), a tendency for higher quality articles to benefit more than lower quality articles from being self-archived.) In condensed-matter physics, Moed has confirmed that the impact advantage occurs early (within 1-3 years of publication). After article-age is adjusted to reflect the date of deposit rather than the date of publication, the enhanced impact of self-archived articles is again interpretable as QB, with articles by more highly cited authors (based only on their non-archived articles) tending to be self-archived more. (But since the citation counts for authors and for their articles are correlated, one would expect much the same outcome from QA too.) The only way to test QA vs. QB is to compare the impact of self-selected self-archiving with mandated self-archiving (and no self-archiving). (The outcome is likely to be that both QA and QB contribute, along with EA, to the impact advantage.)

Henneken, E. A., Kurtz, M. J., Eichhorn, G., Accomazzi, A., Grant, C., Thompson, D., and Murray, S. S. (2006) Effect of E-printing on Citation Rates in Astronomy and Physics. Journal of Electronic Publishing, Vol. 9, No. 2, Summer 2006Kurtz analyzed AA and found that it consisted of at least 2 components:

Henneken, E. A., Kurtz, M. J., Warner, S., Ginsparg, P., Eichhorn, G., Accomazzi, A., Grant, C. S., Thompson, D., Bohlen, E. and Murray, S. S. (2006) E-prints and Journal Articles in Astronomy: a Productive Co-existence (submitted to Learned Publishing)

Kurtz, M. J., Eichhorn, G., Accomazzi, A., Grant, C. S., Demleitner, M., Murray, S. S. (2005) The Effect of Use and Access on Citations. Information Processing and Management, 41 (6): 1395-1402, December 2005

(1) EARLY ACCESS (EA): There is no detectable AA for old articles in astro: AA occurs while an article is young (1-3 years). Hence astro articles that were made accessible as preprints before publication show more AA: This is the Early Access effect (EA). But EA alone does not explain why AA effects (i.e., enhanced citation counts) persist cumulatively and even keep growing, rather than simply being a phase-advancing of otherwise unenhanced citation counts, in which case simply re-calculating an article's age so as to begin at preprint deposit time instead of publication time should eliminate all AA effects -- which it does not.

(2) QUALITY BIAS (QB): (Kurtz called the second component "Self-Selection Bias" for quality, but I call it self-selection Quality Bias, QB): If we compare articles within roughly the same citation/quality bracket (i.e., articles having the same number of citations), the proportion of Arxived articles becomes higher in the higher citation brackets, especially the top 200 papers. Kurtz interprets this is as resulting from authors preferentially Arxiving their higher-quality preprints (Quality Bias).

Of course the very same outcome is just as readily interpretable as resulting from Quality Advantage (QA) (rather than Quality Bias (QB)): i.e., that the Arxiving benefits better papers more. (Making a low-quality paper more accessible by Arxiving it does not guarantee more citations, whereas making a high-quality paper more accessible is more likely to do so, perhaps roughly in proportion to its higher quality, allowing it to be used and cited more according to its merit, unconstrained by its accessibility/affordability.)

There is no way, on the basis of existing data, to decide between QA and QB. The only way to measure their relative contributions would be to control the self-selection factor: randomly imposing Arxiving on half of an equivalent sample of articles of the same age (from preprinting age to 2-3 years postpublication, reckoning age from deposit date, to control also for age/EA effects), and comparing also with self-selected Arxiving.

We are trying an approximation to this method, using articles deposited in Institutional Repositories of institutions that mandate self-archiving (and comparing their citation counts with those of articles from the same journal/issue that have not been self-archived), but the sample is still small and possibly unrepresentative, with many gaps and other potential liabilities. So a reliable estimate of the relative size of QA and QB still awaits future research, when self-archiving mandates will have become more widely adopted.

Henk Moed's data on Arxiving in Condensed Matter physics (cond-mat) replicates Kurtz's findings in astro (and Davis/Fromerth's, in math):

Moed, H. F. (2006, preprint) The effect of 'Open Access' upon citation impact: An analysis of ArXiv's Condensed Matter SectionMoed too has shown that in cond-mat the AA effect (which he calls CID "Citation Impact Differential") occurs early (1-3 years) rather than late (4-6 years), and that there is more Arxiving by authors of higher-quality (based on higher citation counts for their non-Arxived articles) than by lower-quality authors. But this too is just as readily interpretable as the result of QB or QA (or both): We would of course expect a high correlation between an author's individual articles' citation counts and the author's average citation count, whether the author's citation count is based on Arxived or non-Arxived articles. These are not independent variables.

Davis, P. M. and Fromerth, M. J. (2007) Does the arXiv lead to higher citations and reduced publisher downloads for mathematics articles? Scientometics, accepted for publication. See critiques: 1, 2.

(Less easily interpretable -- but compatible with either QA or QB interpretations -- is Moed's finding of a smaller AA for the "more productive" authors. Moed's explanations in terms of co-authorships between more productive and less productive authors, senior and junior, seem a little complicated.)

The basic question is this: Once the AA has been adjusted for the "head-start" component of the EA (by comparing articles of equal age -- the age of Arxived articles being based on the date of deposit of the preprint rather than the date of publication of the postprint), how big is that adjusted AA, at each article age? For that is the AA without any head-start. Kurtz never thought the EA component was merely a head start, however, for the AA persists and keeps growing, and is present in cumulative citation counts for articles at every age since Arxiving began. This non-EA AA is either QB or QA or both. (It also has an element of Competitive Advantage, CA, which would disappear once everything was self-archived, but let's ignore that for now.)

Harnad, S. (2005) OA Impact Advantage = EA + (AA) + (QB) + QA + (CA) + UA. Preprint.Moed's analysis, like Kurtz's, cannot decide between QB and QA. The fact that most of the AA comes in an article's first 3 years rather than its second 3 years simply shows that both astro and cond-mat are fast-developing fields. The fact that highly-cited articles (Kurtz) and articles by highly-cited authors (Moed) are more likely to be Arxived certainly does not settle the question of cause and effect: It is just as likely that better articles benefit more from Arxiving (QA) as that better authors/articles tend to Arxive/be-Arxived more (QB).

Nor is Arxiv the only test of the self-archiving Open Access Advantage. (Let's call this OAA, generalizing from the mere Arxiving Advantage, AA): We have found an OAA with much the same profile as the AA in 10 further fields, for articles of all ages (from 1 year old to 10 years old), and as far as we know, with the exception of Economics, these are not fields with a preprinting culture (i.e., they don't self-archive preprublication preprints but only postpublication postprints). Hence the consistent pattern of OAA across all fields and across articles of all ages is very unlikely to have been just a head-start (EA) effect.

Hajjem, C., Harnad, S. and Gingras, Y. (2005) Ten-Year Cross-Disciplinary Comparison of the Growth of Open Access and How it Increases Research Citation Impact. IEEE Data Engineering Bulletin 28(4) pp. 39-47.Is the OAA, then, QB or QA (or both)? There is no way to determine this unless the causality is controlled by randomly imposing the self-archiving on a subset of a sufficiently large and representative random sample of articles of all ages (but especially newborn ones) and comparing the effect across time.

In the meantime, here are some factors worth taking into account:

(1) Both astro and and cond-mat are fields where it has been repeatedly claimed that the accessibility/affordability problem for published postprints is either nonexistent (astro) or less pronounced than in other fields. Hence the only scope for an OAA in astro and cond-mat is at the prepublication preprint stage.

(2) In many other fields, however, not only is there no prepublication preprint self-archiving at all, but there is a much larger accessibility/affordability barrier for potential users of the published article. Hence there is far more scope for OAA and especially QA (and CA): Access is a necessary (though not a sufficient) causal precondition for impact (usage and citation).

It is hence a mistake to overgeneralize the phys/math AA findings to OAA in general. We need to wait till we have actual data before we can draw confident conclusions about the degree to which the AA or the OAA are a result of QB or QA or both (and/or other factors, such as CA).

For the time being, I find the hypothesis of a causal QA (plus CA) effect, successfully sought by authors because they are desirous of reaching more users, far more plausible and likely than the hypothesis of an a-causal QB effect in which the best authors are self-archiving merely out of superstition or vanity! (And I suspect the truth is a combination of both QA/CA and QB.)

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Monday, November 13. 2006

Self-Archiving and Journal Subscriptions: Critique of PRC Study

SUMMARY: There is no evidence to date that Open Access (OA) self-archiving causes journal cancellations. The Publishing Research Consortium commissioned a survey of acquisitions librarian preferences to see whether they could predict such cancellations in the future using a "Share of Preference model," but the study has a glaring methodological flaw that invalidates its conclusion (that self-archiving will cause cancellations). The study consisted of asking librarians which of three hypothetical products -- A, B or C -- they preferred least and most, for a variety of hypothetical combinations of 6 properties with 3-4 possible values each:

1. ACCESS DELAY: 24-months, 12-months, 6-months, immediate access

2. PERCENTAGE OF JOURNAL'S CONTENT: 100%, 80%, 60%, 40%

3. COST: 100%, 50%, 25%, 0%

4. VERSION: preprint, refereed, refereed+copy-edited, published-PDF;

5. ACCESS RELIABILITY: high, medium, low

6. JOURNAL QUALITY: high, medium, low

No mention was made of OA self-archiving (in order to avoid "bias"); but, as a result, the model cannot make any prediction at all about the effects of self-archiving on cancellations. The questions on which it is based were about relative preferences for acquisition among competing "products" having different combinations of properties, and the model treated OA (0% cost) as if it were just one of those product properties. But self-archived articles are not products purchased by acquisitions librarians: they are papers given away by researchers, anarchically, and in parallel. Hence from the survey's "Share of Preference model" it is impossible to draw any conclusions about self-archiving causing cancellations by librarians, because the librarians were never asked what they would cancel, under what conditions; just what hypothetical products they would prefer over what. And of course they would prefer lower-priced, immediate products over higher-priced, delayed products! But if all articles in all journals were self-archived, the "Share of Preference model" does not give us the slightest clue about what journals librarians would acquire or cancel. Nor does it give us a clue as to what they would do between now (c. 15% self-archiving) and then (100% self-archiving). The banal fact that everyone would rather have something for free rather than paying for it certainly does not answer this question, or fill the gaping evidential gap about the existence, size, or timing of any hypothetical effect of self-archiving on cancellations. Nor does the study's one nontrivial finding: that librarians don't much care about the difference between a refereed author's draft and a published-PDF. (Let us hope that this study will be the last futile attempt to treat research as if it were done in order to generate or protect journal revenues. Even if valid evidence should eventually emerge that OA self-archiving does cause journal cancellations, it would be for the publishing community to adapt to that new reality, not for the research community to abstain from it, and its obvious benefits to research, researchers, their institutions, their funders, and the tax-paying public that funds the funders and for whose benefit the research is conducted.)

Critique of Publishing Research Consortium Study

Stevan Harnad

The following is a critique of:

Chris Beckett and Simon Inger, Self-Archiving and Journal Subscriptions: Co-existence or Competition? An international Survey of Librarians' Preferences. Commissioned by the Publishing Research Consortium from Scholarly Information Strategies Ltd (SIS), a scholarly publishing consultancy. October 2006Because there has so far been no detectable correlation between author self-archiving and journal cancellations, the Publishing Research Consortium commissioned a survey of acquisition librarians' preferences and attitudes about a number of hypothetical alternatives. From the responses a theoretical model was constructed, which predicted cancellations as more self-archived content becomes available. How did the study arrive at this prediction without any actual cancellation data?

The prediction was based on a rather simple methodological flaw: Librarians were given a series of hypothetical choices, each a choice among three hypothetical "products," A, B and C. The librarians were asked to pick which of the three product options they would prefer most and least. Each hypothetical product option consisted of a complicated combination of six properties out of 3-4 possible values per property.

Presenting this array of hypothetical product options as choices to acquisition librarians (apart from being highly complicated and highly hypothetical, with many hidden assumptions) is specious, for among the potential properties of the hypothetical "product" options was the property that some of the options were free.

But a free self-archived journal article is not a product: It is not something that an acquisitions librarian decides whether or not to acquire. Open Access (OA) is not a product-acquisition issue at all: At best (or worst) its a product cancellation issue.

Hence the only credible and direct hypothetical question one could have asked librarians about self-archived journal articles (and even then there would be no guarantee that librarians would actually do as they predicted they would do under the hypothetical conditions) would be about the circumstances under which they think they would cancel existing journals:

And even that question is laden with highly speculative and even indeterminate assumptions: How could librarians (or anyone) know what percentage of a journal was accessible for free, self-archived, for any particular journal?"Would you cancel journal X if 100% of its articles were accessible free online (80%? 60%? 40%?)? If they were accessible immediately (after 6 months? 12? 24?)?"

And what about interactions between journal X and journal Y? (How to spend a given acquisitions budget -- what to acquire and what to cancel -- is presumably a comparative decision, and we are asking about the keep/cancel trade-offs.)

But what if 60% of all journals were free online (immediately? after 12 months?)? (Acquisition/cancellation decisions today are largely competitive ones: X gets cancelled in favour of Y. The rules of this trade-off game would presumably change if all journals were roughly on a par for their percentage of freely available online content or the length of the delay before it is freely available.)

Straightforward questions on what a librarian predicts they would cancel (in favour of what) under what hypothetical conditions (and how those conditions could be ascertained) might possibly have some weak predictive value. But such straightforward questions are not what this series of questions about preferences among hypothetical "product options" asked.

[Even straightforward hypothetical answers to straightforward hypothetical questions may not have any predictive value if the hypotheses are far-fetched or unfamiliar enough, if they have hidden or incoherent assumptions: I frankly don't believe there is a librarian alive who has a clue as to what they would keep or cancel if the self-archived versions of all journal articles were suddenly available free online today -- let alone what they would do as all journal contents gradually approached 100% availability, at various (uncertain) speeds, from a trajectory of increasing (but uncertain) free content (40% to 60% to 80%) and/or decreasing delay (24 months to 12 months to 6 months).]

And that's without mentioning intangibles such as any continuing demand for the paper edition, etc., nor how librarians could know the percentages available, how quickly the percentages would grow, and at what relative rate they would grow among more and less important journals, more and less expensive journals.

But it was not even these straightforward, if highly speculative, questions that were asked of librarians in this survey. Instead, they were asked to pick the most and least favoured option among three hypothetical "products," A, B and C, with a variety of complicated combinations of 6 hypothetical properties, which could each take 3-4 values:

1. ACCESS DELAY: 24-months, 12-months, 6-months, immediate access

2. PERCENTAGE OF JOURNAL'S CONTENT: 100%, 80%, 60%, 40%

3. COST: 100%, 50%, 25%, 0%

4. VERSION: preprint, refereed, refereed+copy-edited, published-PDF;

5. ACCESS RELIABILITY: high, medium, low

6. JOURNAL QUALITY: high, medium, low

In each case, products A, B and C were given some combination of the values on properties 1-6, and the librarian had to choose which of the 3 combinations they most and least preferred.

From samples of these combinations (interpolated and extrapolated within and between librarians) the survey concludes that:

PRC: A major study of librarian purchasing preferences has shown that librarians will show a strong inclination towards the acquisition [sic] of Open Access (OA) materials as they discover that more and more learned material has become available in institutional repositories.(1) OA materials are not "acquired" (and it is both misleading and absurd to cast either the questions or the responses in an acquisitions context). Non-OA products are acquired, and the availability of OA versions of them might or might not induce cancellation in favour of other non-OA products under various circumstances (that are not even touched upon by this study or its methodology).

Why would the model assume arbitrary differential rates of OA growth among journals rather than roughly uniform growth across all journals in each field (apart form random fluctuations)? And if there were systematic differential OA growth within a field, wouldn't librarians' decisions depend very much on the field, and on which journal contents happen to became OA faster, rather than on any general predictions generated from this theoretical model?

(2) Nothing whatsoever was determined about what happens as more and more OA becomes available all round, nor about how availability would be ascertained, nor at what rate OA would grow and be ascertained. There were merely static questions about 3 hypothetical competing "products," some stipulated to be PP% OA within MM months.

PRC: Overall the survey shows that a significant number of librarians are likely to substitute OA materials for subscribed resources, given certain levels of reliability, peer review and currency of the information available. This last factor is a critical one -- resources become much less favoured if they are embargoed for a significant length of time.The survey shows nothing whatsoever about libraries substituting OA material for anything, because free self-archived content is not something a subscriber institution (library) provides (by buying it in) but something an author institution provides, via its IR, by self-archiving it.

If the questions had been forthrightly put as pertaining to cancellation decisions under various hypothetical conditions, then at least we would have had librarians' speculations about what they think they would cancel under those hypothetical conditions. But instead we have inferences from a model based on least- and most-preferred "product" options having little or no bearing on any question other than the librarians' preferences for the hypothetical properties: They prefer journals with lower prices, whose content is higher quality, more reliable, more immediate, peer-reviewed, and preferably 100% of it. (Librarians don't much care whether the peer-reviewed article is the author's final draft or the publisher's PDF, as long as it's peer-reviewed: That is a genuine finding of this study!)

There is no way at all to interpolate or extrapolate from data like these to draw valid or even coherent conclusions about self-archiving and cancellations, with or without a "conjoint analysis" model.

PRC: One of the key benefits of the conjoint analysis approach used in this survey was the removal of bias by not referring, when testing different product configurations, to any named incarnations of content types, including subscription journals, licensed full-text (or aggregated) databases, or articles on OA repositories.This "bias" was eliminated at the cost of making it a questionnaire about acquisitions among a variety of competing "products" when it should have been a questionnaire about cancellations under a variety of hypothetical OA conditions (many of them unascertainable, hence moot).

PRC: The survey tested librarians' preferences for a series of hypothetical and unnamed products frequently showing unfamiliar combinations of attributes -- such as a fully priced journal embargoed for 24 months, or content at 25% of the price but through an unreliable service. By taking this approach, the survey measured librarians' preferences for an abstract set of potential products thus avoiding any pre-conceived preferences for named products, such as journals, licensed full- text (aggregated) databases or content on OA repositories.Indeed. But OA is not an alternative product for acquisition: it is a property that might or might not induce cancellation in favor of other products under certain hypothetical (and presumably competitive) conditions.

PRC: The data were abstracted into a "Share of Preference" model (or simulator) which has then been used to model real-life products and thus create predictions for librarians' real-life preferences for these products. It is therefore possible to go beyond the comparisons, in this work, of journals versus OA and to model other preferences, such as between OA and licensed full-text databases.The "Share of Preference model" might be viable when the preference really concerns competing products for acquisition, with a variety of rival properties, but it fails completely when applied to free non-products, not for acquisition at all, but treated as if they were just another among the rival properties of products competing for acquisition.

We could have said a-priori that librarians (like all consumers) will prefer a higher quality product over a lower quality product, 100% of a product over 60% of a product, an immediate product over a delayed product, a lower-priced product over a higher-priced product. A "Share of Preference model" could give some rough rank orders for those various combinations.

It seems natural to add to such a "Share of Preference model" that consumers will prefer a free product over a priced product, except that we are talking here about acquisitions librarians, who do not "acquire" free products but merely buy or cancel priced journals. This study simply does not and cannot indicate under what OA conditions they will cancel what for what.

The following (mild) conclusions, are the only ones that can be drawn:

PRC: There is a strong preference for content that has undergone peer review.Yes, and librarians don't much care whether the peer-reviewed content is the publisher's PDF version or the author's final version -- except that the publisher's PDF is for sale and the author's final draft is not! Nor does the model tell us under what conditions, if both versions are available for a journal X, librarians would cancel the publisher's PDF (and in favour of what journal Y?). The question is never even raised. That's the question the study was designed to answer, but the method could not answer it. The survey might as well have asked the librarians directly, for X/Y pairs of hypothetical or actual journals -- rather than A/B/C triplets of hypothetical "products" -- banal questions such as:

I suspect that it is because -- in the absence of any actual evidence of self-archiving causing cancellations -- a survey on hypothetical cancellations of journal X in favour of journal Y (or no journal at all) under various %OA and months-delay conditions would not have been very convincing or informative that the survey instead resorted to "Share of Preference" modelling. But I'm afraid the outcome is even less convincing."If 100% of X were immediately available for free online and Y was not, and your users needed X and Y equally, and you could not afford both, and you currently subscribed to X and not to Y, would you cancel X for Y?"

PRC: How soon content is made available is a key determinant of content model preference in librarian's acquisition behaviour; delay in availability reduces the attractiveness of a product offering.Yes, immediate access is preferable to delayed access. And, no doubt, if/when librarians are ever inclined to cancel a journal X because PP% of its articles are freely available, they are more likely to do so if that PP% is immediately available than if it is only available 24 months after publication. But we could have guessed that without this study. The question is: Under what circumstances are librarians going to cancel what, when? This study does not and cannot tell us. Relative preference models can only tell us that they are more likely to do it under these conditions than under those conditions (and we already knew all that).

Having said all this, it is important to state clearly that, although there is still no evidence at all of self-archiving causing cancellations, it is possible, indeed probable, that self-archiving will cause some cancellations, eventually. No one knows (1) how soon it will cause cancellations, nor (2) how many cancellations it will cause. That all depends on (a) how much demand there still is for the print edition and (b) for the journal's online edition at that time, (c) for how long that demand lasts, and (d) how quickly self-archiving grows and approaches 100%. (Perhaps someone should do a survey on people's predictions about those factors!)

But regardless of any of this -- and regardless also of the validity or invalidity of the present survey -- the possibility or probability of cancellation pressure is most definitely not the basis on which the research community should decide whether or not to self-archive and whether or not to mandate self-archiving. That decision must be based entirely on the benefits of OA self-archiving for research access, impact, productivity and progress -- definitely not on the basis of the possibility of revenue losses for publishers.

We do well to remind ourselves that these questions are not primarily about what is or is not good for the publishing industry. They are about what is and is not good for research, researchers, their institutions, their funders, and the tax-paying public that funds the funders. Research is supported and conducted and peer-reviewed and published for the sake of research progress and applications, not in order to support the publishing industry, or to protect it from risk.

And what is certain is that peer-reviewed research publishing can and will successfully adapt to Open Access: How can it fail to do so, when it is researchers who conduct the research, write the articles, perform the peer review, read, use, apply and cite the research, and, now, provide online access to it as well? Publishers are performing a valuable service (in implementing the peer review and in providing a paper and online edition) but it is publishing that must adapt to what is best for research in the online age, definitely not research that must adapt to what is best for publishing. And publishing can and will adapt.

(I might add that Dr. Alma Swan is not the super-ennuated (sic) Proustian personage repeatedly cited in this PRC survey, but the cygnine author of a number of landmark surveys, one of them reporting the only existing evidence -- negative -- for a causal connection between OA self-archiving and cancellations.)Berners-Lee, T., De Roure, D., Harnad, S. and Shadbolt, N. (2005) Journal publishing and author self-archiving: Peaceful Co-Existence and Fruitful Collaboration

Henneken, E. A., Kurtz, M. J., Warner, S., Ginsparg, P., Eichhorn, G., Accomazzi, A., Grant, C. S., Thompson, D., Bohlen, E. and Murray, S. S. (2006) E-prints and Journal Articles in Astronomy: a Productive Co-existence (submitted to Learned Publishing)

Swan, A. (2005) Open access self-archiving: An Introduction. JISC Technical Report.

On Thu, 16 Nov 2006, Simon Inger and Chris Beckett replied:

1. The methodology deployed and the entire point of conducting a conjoint survey at all:Simon and Chris are, I think, quite right that there is considerable danger of bias, in one direction or the other, when acquisitions librarians are asked to speculate about what they would do in hypothetical future scenarios.

We decided to undertake a conjoint survey because we felt that other attitudinal surveys of what future intentions might be were highly prone to being bogged down exactly because surveyees were asked in absolute terms to what extent they would like one scenario, and then another, without ever asking them to choose between them.

But it is not at all clear that the method Simon and Chris used corrects for these biases, or merely changes the subject (from predicting cancellations under hypothetical conditions, to merely expressing product/property preferences under hypothetical conditions).

A survey that asks people if they like steak to eat, and then asks if they like chicken to eat, is not as powerful as a survey that asks them to choose between steak and chicken. Bring in another variable, such as, "how well done do you like your meat?" and you get a very different answer depending on whether the surveyee preferred steak or chicken in the first place. By combining these factors with others through a conjoint survey, you might just find out how bad the steak has to be before chicken tartare starts to command a market share! We hope this illustrates the whole purpose of the conjoint in applying it to the situation that publishing currently faces; it forces people to reveal the true underlying factors in their decision-making in a way that hasn't been done before.The conjoint method is no doubt a good method for estimating or ranking relative product property preferences in general. But in the particular case of library journal acquisitions/cancellations, OA and self-archiving, as noted, the method not only does not remedy the the possibility of bias, but it bypasses the question of cancellations altogether -- the question that I take it that (for lack of actual cancellation data) the survey was trying to answer.

2. Whether or not OA can be considered a product in any meaningful sense:I'm afraid I cannot agree with this reasoning: The mobile phone analogy (as well as the meat analogy) begs the question, because in both cases the product and the client are unambiguous, and it is a straightforward quid pro quo: Would the client rather buy steak or chicken? mobile phone or home phone? The choice is a direct trade-off between (two) competing products. And I also agree that if one of them were free, that would not change anything: It would still be this versus that.

Can articles in Open Access repositories be considered a product and one that librarians may select instead of journals? Absolutely they can. Is the issue here that they are free via OA, or that they are not organised and packaged? If we were to stand on a street corner and give away mobile phones, they would be every bit as much as a product as one you paid for in a shop. Would we cause some people not to go into the shop and buy a mobile - sure we would. Would some people not trust the mobile we gave them and buy one anyway - yes they would. Would some people use our mobiles as a spare and buy another anyway - yes they would do that too. A survey might tell you in what proportions people would undertake these actions. But you can be certain that at least some of the people would use the mobile we gave them and postpone or cancel the acquisition of a paid-for phone. So we believe that articles via OA, even though they are free, are still very much a product. So perhaps they should not be considered as a product because they are not organised into product-shaped offerings, like journals are.

But that's not at all how it is with paid journals vs. self-archived OA content.

Let's start with an easy example: Suppose we weren't talking about anarchically self-archived articles, but about OA vs. non-OA journals. And to make it even simpler, let us suppose (as is the case with, for example, with BioMed Central journal institutional "memberships"), that a library has a choice between two journals that are equated, somehow, in terms of readership, quality, subject-matter and usage-needs of institutional users, that there is only enough money to afford one of them, and that they differ in that one is subscription-based and the other is based on institutional "membership" fees (for publishing institutional articles).

That's an odd choice situation for an acquisitions librarian (since in one case the librarian is buying in the journal's content, and in the other the librarian is paying for the institution's own outgoing content), but perhaps librarians would intuit that they get better value for their institutional money from the second journal (especially if they consult with their institutional users, and they agree -- a detail not mentioned by the survey, which seems to assume subscription/cancellation decisions are all or mostly in the hands of the librarians!).

But that would be a prima-facie plausible prediction by librarians, about what they would prefer and do under those conditions. Even more plausible would be a least/most choice involving three equivalent journals, when the library can afford only two journals, and the third is an OA journal for which someone else (other than the library) pays the institutional OA charges, making it effectively "free" to the library. Under those conditions the librarian could realistically say they'd prefer to "cancel" the free (OA) journal (i.e., just let users download it for themselves, free, from the web) so they can use all available money saved for the other two journals.

(Of course, the tricky part is that a pure OA journal [e.g., BMC or PLoS] is not one that a library subscribes to anyway! (Actually, most OA journals are available for subscription, and do not charge author-institutions for publication. Possibly, just possibly, the results of the PRC survey might have some predictive value as to whether that kind of OA journal is likely to be cancelled; but so far there is little actual evidence of that happening either, though it might! Keep your eyes on the longevity of the majority of the OA journals in DOAJ that do not change for publication but make ends meet from subscriptions.)

But we have not yet come to third option, the one that the survey was commissioned by PRC to test, and that is author self-archiving, and whether that will cause cancellations.

It is for author self-archiving that the question of the extra properties of percentage content, and length of embargo had to be introduced and varied in this study. Length of embargo is not the problem, but percentage content very much is, and so is the fact that all self-archived content is free. Here we are square in the middle of the profound difference between OA journals (a complete, quid-pro-quo product) and OA self-archiving (an anarchic process, applying to only a portion of content, and an unknown proportion at that, growing -- but again at an unknown rate -- across time).

With journals (including OA journals), it's journal X vs journal Y ("product" X vs. "product" Y): Shall I purchase X and cancel Y, or vice versa? Shall I purchase X and Y and cancel Z? These are presumably familiar, hence realistic acquisitions librarian questions (in consultation with users -- who were not surveyed in this survey!).

But what is the question with journals vs. anarchic self-archived content? What is it that a librarian is contemplating buying versus cancelling when what they are really faced with is a choice between a journal and a distributed, anarchic and uncertain percentage of its contents (with no indication of how it is even knowable what that percentage is)?

But let's overlook that and agree that if it were a question of buying vs. cancelling journal X based on some estimate of the percentage of its contents that is available for free in self-archived form, librarians could dream up a hypothetical preference from a combination of properties such as journal quality, journal price, percentage free content, and embargo length.

But that would be journal X vs. not-X, or journal X vs. Y. What is the librarian's conjecture as to their preference when all journals have PP% of their content self-archived? That's not a journal vs. journal acquisition/cancellation question any more: It's asking librarians to second-guess the OA future: Are we to infer from the conjoint preference data that they would cancel all journals under those conditions (second-guessing their users on how long they might, for example, continue to value the paper edition?).

The analogy with chicken and steak would be whether conjoint chicken/steak or mobile/home-phone property preferences predict whether and when people would stop paying for food or phones altogether because they were somehow miraculously available free with a certain probability (and/or) delay) for a certain percentage of the potential calls and time. We know that if it were all free, immediately and with certainty, everyone would prefer that. But do conjoint preferences tell us one bit more than that? (And again we leave out the parties of the second part -- the institutional users - as well as the paper edition and how they might feel about it, and for how long...)

That may be so, for now, but at the same time we are aware of organisations that are building products which combine the power of OAI-PMH (and the crawling power of Google); existing abstracting & indexing databases; publisher operated link servers; and library operated link servers: to build an organised route to OA materials - a route that would allow a non-subscriber of a journal article to be directed to the free OA repository version instead. Once these products exist we are sure our research indicates that some librarians at least will actually switch to OA versions for some of their information needs, while others will continue to purchase the journal product for a whole raft of reasons and others will provide, i.e. acquire, both options.Let me quickly agree about what I would not have contested from the very outset:

(1) Without the conjoint survey, I would already have agreed that everyone prefers to have something for free rather than paying for it.

(2) I also happen to believe, personally, that once 100% OA self-archiving has been reached -- but I don't know how soon it will be reached, nor how soon after it is reached this will happen -- there will be cancellation pressure that will lead to downsizing and a transition to OA publishing.

But it is still a fact that there is as yet no evidence of cancellation pressure, and I do not at all see how the conjoint preference study tells us any more than we already know (and don't know) about whether and when and how much cancellation pressure will ever be caused by self-archiving.

(I have to add that I profoundly doubt that in the OA world libraries and librarians will mediate in any way between users and the refereed journal article literature. Library mediation will be as supererogatory as it is with what users do with google today.)

3. The issue of bias:I think the attempt to avoid all of these emotional (and notional) biases was a commendable one, and it would have been successful too, if the conjoint-preference method had been amenable to analysing the anarchic phenomenon of author self-archiving and its likely effect on librarian acquisition/cancellation. But it is not, because anarchic, blanket self-archiving is simply not an acquisition/cancellation matter.

The whole Open Access debate evokes an emotional response from publishers, librarians and researchers on both sides of the debate. At the same time, so does the word "cancellation". For that matter, so does the phrase "serials crisis". We wanted to avoid using all of these phrases in the research so as not to cloud people's judgement in favour of their beliefs alone. This is one way of avoiding one type of bias. Specifically the type of bias we sought to eliminate was an emotional bias, not a bias for or against OA per se. It can be equally well argued that another survey should be done with these words actually mentioned. The results may well be different. But no more or less valid than ours - such a survey would be measuring a different thing. It is up to each individual reader of the report to decide which kind of response and hence survey they would prefer.

Acquisition/cancellation concerns what to buy, retain and cancel from among a finite set of products using a finite acquisitions budget. It is a competitive matter: competition between products. Anarchic self-archiving is gradual and uncertain, but it generates only an all-or-none cancellation question, and one that is in no way addressed by the conjoint preferences method.

(I am sure, by the way, that librarians could have been polled -- directly and unemotionally -- about how much journal content they thought would have to be self-archived before they would no longer need to purchase journals at all -- but I don't think their speculations on that would have been very informative.)

I do think, though, that one indirect finding on this question did emerge from the conjoint method (and it surprised me, considering how strident some librarians have been in the opposite direction in the past!): It does seem that librarians are surprisingly indifferent to the difference between an author's refereed final draft and the publisher's PDF. That's very interesting (and it's progress: in librarian awareness and understanding of what researchers really do and don't need!).

4. The statement of apparently obvious or banal findings:Agreed. (But that's hardly very surprising either! Nor informative about whether and when self-archiving causes cancellations.)

The critique states that some of the findings are obvious and banal. "The fact that everyone would like something for free rather than paying for it", for example. In fact the survey shows that not everyone would prefer that. Even in a completely like for like situation. Possibly because people are suspicious of free things.

Much more important, however, is how the decision becomes qualified by other factors - and to what extent they are qualified. (Would you like free raw chicken for dinner or paid-for cooked chicken?) Look closely and the results show that the lure of "free" has only so much pulling power, and a combination of other factors pull more potently against it. So in themselves the importance of each of the attributes has limited value - it is in combination that their true meaning comes through.I think what you are saying here is that in varying the combination of 6 properties, each with 3-4 possible values, you founded a complex preferential structure. But it still doesn't tell us whether and when self-archiving will cause cancellations.

5. The validity of inferring cancellation behaviour from the findings:For those (like me) who happen to think that 100% OA self-archiving is likely eventually to cause cancellations, downsizing, and a transition to the OA cost-recovery, but that there is as yet no evidence of this, and that it is a matter of complete uncertainty how fast the self-archiving will grow, how soon the cancellation pressure will be felt, and how strong the cancellation pressure will be -- this study did not provide any new information.

So, can we infer cancellation behaviour from the results? Yes, we can. Because it is unrealistic to expect that everyone that expresses a preference for acquiring a product that looks very much like content on OA repositories would still continue to acquire a paid-for version. Some will, of that we have very little doubt. But likewise some won't. To that end I think we can infer cancellation will occur. It may be after someone has provided an organisational layer on top of the repositories. It may be after improved librarian awareness of the alternative has occurred. And it may require way more than 15% of the material to be available on OA.

For those empiricists (with whom I have some sympathy too), who simply say there is no evidence at all yet that self-archiving causes cancellations -- and that even in the few fields where self-archiving has been at or near 100% for some years there is still no such evidence -- it is likewise true that this study has not provided any new evidence: neither about whether there will be cancellations, nor, if so, about when and how much.

Stevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Thursday, November 9. 2006

Proportion Open Access in Biomedical Sciences

Comments on:

The authors also note that their estimate of 10.9% self-archiving is lower than Swan's estimate of 49% (but Swan's sample was for all disciplines, and the 49% referred only to the proportion of respondents who had self-archived at least one article).

Presumably "articles in journals that had an Impact Factor" means articles in journals indexed by Thompson ISI. If so, then the finding that fewer ISI articles are OA means that fewer ISI journals are OA and/or fewer authors of articles in non-ISI journals self-archive.

There is considerable scope for variability here (by year, by field, by quality, and by country), but it is certainly true that fewer ISI journals than non-ISI journals are OA (though "Hybrid OA"/Open-Choice may change that).

Several studies -- from Lawrence 2001 to Hajjem et al 2005 -- have reported that there is a positive correlation between citation-bracket and OA (the higher the citations, the more likely the article is OA), and there is disagreement over how much of this effect is a causal Quality Advantage (OA causing higher citations for higher quality articles) or a self-selection Quality Bias (authors of higher quality articles being more likely to make them OA, one way or the other). The present results don't resolve this, as they go both ways.

Clearly, more studies are needed. But even more than that, more OA is needed!

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Matsubayashi, Mamiko and Kurata, Keiko and Sakai, Yukiko and Morioka, Tomoko and Kato, Shinya and Mine, Shinji and Ueda, Shuichi (2006) Current Status of Open Access in Biomedical Field - the Comparison of Countries Related to the Impact of National Policies. 2006 Annual Meeting of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, Austin, Texas.This study randomly sampled 4756 biomedical articles published between January and September in 2005 and indexed in PubMed, hand-checking how many of them were OA, and if so how: via OA journal (gold) or self-archiving (green, via IRs or websites). Its findings:

75% of the sampled 4756 articles were available online.The authors note that their 25% OA estimate in biomedical sciences in 2005 is higher than Hajjem et al's s estimate of 15% OA in biology and 6% OA in health (but Hajjem et al's sample was for 1992-2003, based only on articles indexed by Thompson ISI, and explicitly excluded articles published in OA journals, hence the relevant comparison figure is the present study's 10.9% for self-archiving).

25% of the sampled 4756 articles were OA.

Over 70% of the 1189 (25%) OA articles were OA via OA or Hybrid OA journals

10.9% of the 1189 (25%) OA articles were OA via IRs or websites (6.0% and 4.9% respectively).

20.6% of the articles in journals with an Impact Factor were OA.

30.8% of the articles in journals with no Impact Factor were OA.

Countries were compared, but the variation is more likely in national practices than in national policies.

The authors also note that their estimate of 10.9% self-archiving is lower than Swan's estimate of 49% (but Swan's sample was for all disciplines, and the 49% referred only to the proportion of respondents who had self-archived at least one article).

Presumably "articles in journals that had an Impact Factor" means articles in journals indexed by Thompson ISI. If so, then the finding that fewer ISI articles are OA means that fewer ISI journals are OA and/or fewer authors of articles in non-ISI journals self-archive.

There is considerable scope for variability here (by year, by field, by quality, and by country), but it is certainly true that fewer ISI journals than non-ISI journals are OA (though "Hybrid OA"/Open-Choice may change that).

Several studies -- from Lawrence 2001 to Hajjem et al 2005 -- have reported that there is a positive correlation between citation-bracket and OA (the higher the citations, the more likely the article is OA), and there is disagreement over how much of this effect is a causal Quality Advantage (OA causing higher citations for higher quality articles) or a self-selection Quality Bias (authors of higher quality articles being more likely to make them OA, one way or the other). The present results don't resolve this, as they go both ways.

Clearly, more studies are needed. But even more than that, more OA is needed!

Stevan HarnadReferences

Hajjem, C., Harnad, S. and Gingras, Y. (2005) Ten-Year Cross-Disciplinary Comparison of the Growth of Open Access and How it Increases Research Citation Impact. IEEE Data Engineering Bulletin 28(4) pp. 39-47.

Swan, A. (2006) The culture of Open Access: researchers' views and responses, in Jacobs, N., Eds. Open Access: Key Strategic, Technical and Economic Aspects, chapter 7. Chandos.

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Friday, October 27. 2006

Paragraph-Based Quotation in Place of PDF/Page-Based

In the online age, page/line-based quotation is obsolete (for current and forward-going text). Pages are and have always been arbitrary entities. A document's natural landmarks are sections, paragraphs and sentences. That is how quotations and passages should be cited, not by page numbers (though page numbers can be added in parens as a courtesy and curiosity, for continuity, for the time being, while pages -- and PDF -- scroll inexorably toward their natural demise).

It goes without saying that all quotations, citations and references should be hyperlinked. I am sure that XML documents will be tagged for section number, paragraph number and sentence number, so that it will be natural not only to pinpoint the passage to which one wishes to refer but to hyperlink directly to it (especially for quote/commenting).

This answers, in passing, one faint concern about the self-archiving of authors' final refereed drafts instead of the published PDF: "How will I specify the location of passages I wish to single out or quote?" The answer is paragraph numbers (or, if you want to be even more precise, section numbers, paragraph numbers and sentence spans). They have the virtue of not only being autonomous and ascertainable from the document itself, but they are independent of arbitrary pagination and PDF. (They will also be useful for digitometric analyses.)

(I proposed this rather trivial and obvious online solution in Psycoloquy in the early 90's -- though I'm sure I wasn't the first -- and APA at last began recommending it in 2001 or so.)

American Scientist Open Access Forum

It goes without saying that all quotations, citations and references should be hyperlinked. I am sure that XML documents will be tagged for section number, paragraph number and sentence number, so that it will be natural not only to pinpoint the passage to which one wishes to refer but to hyperlink directly to it (especially for quote/commenting).

This answers, in passing, one faint concern about the self-archiving of authors' final refereed drafts instead of the published PDF: "How will I specify the location of passages I wish to single out or quote?" The answer is paragraph numbers (or, if you want to be even more precise, section numbers, paragraph numbers and sentence spans). They have the virtue of not only being autonomous and ascertainable from the document itself, but they are independent of arbitrary pagination and PDF. (They will also be useful for digitometric analyses.)

(I proposed this rather trivial and obvious online solution in Psycoloquy in the early 90's -- though I'm sure I wasn't the first -- and APA at last began recommending it in 2001 or so.)

Harnad, S. (1995) Interactive Cognition: Exploring the Potential of Electronic Quote/Commenting. In: B. Gorayska & J.L. Mey (Eds.) Cognitive Technology: In Search of a Humane Interface. Elsevier. Pp. 397-414.Stevan Harnad

Light, P., Light, V., Nesbitt, E. & Harnad, S. (2000) Up for Debate: CMC as a support for course related discussion in a campus university setting. In R. Joiner (Ed) Rethinking Collaborative Learning. London: Routledge.

Harnad, S. (2003/2004) Back to the Oral Tradition Through Skywriting at the Speed of Thought. Interdisciplines. Retour à la tradition orale: écrire dans le ciel à la vitesse de la pensée. Dans: Salaün, Jean-Michel & Vendendorpe, Christian (réd.). Le défis de la publication sur le web: hyperlectures, cybertextes et méta-éditions. Presses de l'enssib.

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Saturday, October 14. 2006

The Special Case of Astronomy

Update Jan 1, 2010: See Gargouri, Y; C Hajjem, V Larivière, Y Gingras, L Carr,T Brody & S Harnad (2010) “Open Access, Whether Self-Selected or Mandated, Increases Citation Impact, Especially for Higher Quality Research”

Update Feb 8, 2010: See also "Open Access: Self-Selected, Mandated & Random; Answers & Questions"

Michael Kurtz (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics) has provided some (as always) very interesting and informative data on the special case of research access and self-archiving practices in Astronomy. His data show that:SUMMARY: Astronomy is unusual among research fields in that all research-active astronomers already have full online access to all relevant journal articles via institutional subscriptions (because astronomy has only a small closed circle of core journals). Many astronomy articles are also self-archived as preprints prior to peer review and publication, but usage all shifts to the published version as soon as it is available. Self-archiving, even where it is at or near 100%, has no effect at all on subscriptions or cancellations. The Open Access (OA) citation advantage hence reduces to merely an "Early Access Advantage" in astronomy, because all postprints are accessible to everyone. There is also the much-reported positive correlation between the citation counts of articles and the proportion of them that were self-archived. This is no doubt partly a self-selection effect or "Quality Bias" -- with the better articles more likely to be self-archived. But this is unlikely to be all or most of the source of the OA advantage even in astronomy -- let alone in most other fields, where the postprints are not all accessible to all active researchers. The most important component of the OA advantage in general is that OA removes the access and usage barriers that prevent the better work from having its full potential impact (Quality Advantage). In astronomy, where those access barriers hardly exist, there is still a measurable OA advantage, but mostly just because of Early Advantage (and self-selection). With all postprints accessible, Competitive Advantage is restricted to the prepublication phase; Usage Advantage (downloads) can be estimated: downloads are doubled by universal online accessibility. And the Quality Advantage no doubt persists (though it is difficult to estimate independently).

(1) In astronomy, where all active, publishing researchers already have online access to all relevant journal articles (a very special case!), researchers all use the versions "eprinted" (self-archived) in Arxiv first, because those are available first; but they all switch to using the journal version, instead of the self-archived one, as soon as the journal version is available.

That is interesting, but hardly surprising, in view of the very special conditions of astronomy: If I only had access to a self-archived preprint or postprint first, I'd used that, faute de mieux. And as soon as the official journal version was accessible -- assuming that it's equally accessible -- I'd use that.

But these conditions -- (i) open accessibility of the eprint before publication, (ii) in one longstanding central repository (Arxiv), for many and in some cases most papers, and (iii) open accessibility of the journal version of all papers upon publication -- is simply not representative of most other fields! In most other fields, (i') only about 15% of papers are available early as preprints or postprints, (ii') they are self-archived in distributed IRs and websites, not one central one (Arxiv), and (iii') the journal versions of many papers are not accessible at all to many of the researchers after publication.

That's a very different state of affairs (outside astronomy and some areas of physics).

(2) Kurtz's data showing that astronomy journals are not cancelled despite 100% OA are very interesting, but they too follow almost tautologically from (1): If virtually all researchers have access to the journal version, and virtually all of them prefer to use that rather than the eprint, it stands to reason that it is not being cancelled! (What is cause and what is effect there is another question -- i.e., whether preference is driving subscriptions or subscriptions are driving preference.)

(3) In astronomy, as indicated by Kurtz, there is a small, closed circle of core journals, and all active researchers worldwide already have access to all of them. But in many other fields there is not a closed circle of core journals, and/or not all researchers have access. Hence access to a small set of core journals is not a precondition for being an active researcher in many fields -- which does not mean that lacking that access does not weaken the research (and that is the point!).

(4) I agree completely that there is a component of self-selection Quality Bias (QB) in the correlation between self-archiving and citations. The question is (4a) how much of the higher citation count for self-archived articles is due to QB (as opposed to Early Advantage, Competitive Advantage, Quality Advantage, Usage Advantage, and Arxiv (Central) Bias)? And (4b) does self-selection QB itself have any causal consequences (or are authors doing it purely superstitiously, since it is has no causal effects at all)? The effects of course need not be felt in citations; they could be felt in downloads (usage) or in other measures of impact (co-citations, influence on research direction, funding, fame, etc.).

The most important thing to bear in mind is that it would be absurd to imagine that somehow OA guarantees a quality-blind linear increment to the usage of any article, regardless of its quality. It is virtually certain that OA will benefit the better articles more, because they are more worth using and trying to build upon, hence more handicapped by access-barriers (which do exist in fields other than astro). That's QA, not QB. No amount of accessibility will help unciteable papers get used and cited. And most papers are uncited, hence probably unciteable, no matter how visible and accessible you may try to make them!

(5) I think we agree that the basic challenge in assessing causality here is that we have a positive correlation (between proportion of papers self-archived and citation-counts) but we need to analyze the direction of the causation. The fact that more-cited papers tend to be self-archived more, and less-cited papers less is merely a restatement of the correlation, not a causal analysis of it: The citations, after all, come after the self-archiving, not before!

The only methodologically irreproachable way to test causality would be to randomly choose a (sufficiently large, diverse, and representative) sample of N papers at the time of acceptance for publication (postprints -- no previous preprint self-archiving) and randomly impose self-archiving on N/2 of them, and not on the other N/2. That way we have random selection and not self-selection. Then we count citations for about 2-3 years, for all the papers, and compare them.

No one will do that study, but an approximation to it can be done (and we are doing it) by comparing (a) citation counts for papers that are self-archived in IRs that have a self-archiving mandate with (b) citation counts for papers in IRs without mandates and with (c) papers (in the same journal and year) that are not self-archived.

Not a perfect method, problems with small Ns, short available time-windows, and admixtures of self-selection and imposed self-archiving even with mandates -- but an approximation nonetheless. And other metrics -- downloads, co-citations, hub/authority scores, endogamy scores, growth-rates, funding, etc. -- can be used to triangulate and disambiguate. Stay tuned.

Now some comments:

On Tue, 10 Oct 2006, Michael Kurtz wrote:

"Recently Stevan has copied me on two sets of correspondance concerning the OA citation advantage; I thought I would just briefly respond to both.And it also shows how anomalous Astronomy is, compared to other fields, where it is certainly not true that every researcher has subscriptions to the main journals...

"Besides our IPM article: http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2005IPM....41.1395K we have recently published two short papers, both with graphs you might find interesting.

"The preprint will appear in Learned Publishing http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2006cs........9126H E-prints and Journal Articles in Astronomy: a Productive Co-existence

"and this is in the J. Electronic Publishing http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2006JEPub...9....2H Effect of E-printing on Citation Rates in Astronomy and Physics

"There is a point I would like to emphasize from these papers. Figure 2 of the Learned Publishing paper shows that the number of ADS users who read the preprint version once the paper has been released drops to near zero. This shows that essentially every astronomer has subscriptions to the main journals, as ADS treats both the arXiv links and the links to the journals equally; also it shows that astronomers prefer the journals."

"Figure 5 of the J Electronic Publishing paper also shows that there is no effect of cost on the OA reads (and thus by extension citation) differential. Note in the plot that there is no change in slope for the obsolescence function of the reads (either of preprinted or non-preprinted) at 36 months. At 36 months the 3 year moving wall allows the papers to be accessed by everyone, this shows clearly that there is no cost effect portion of the OA differential in astronomy. This confirms the conclusion of my IPM article."And it underscores again, how unrepresentative astronomy is of research as a whole.

"Citations are probably the least sensitive measure to see the effects of OA. This is because one must be able to read the core journals in order to write a paper which will be published by them. It is really not possible for a person who has not been regularly reading journal articles on, say, nuclear physics, to suddenly be able to write one, and cite the OA articles which enabled that writing. It takes some time for a body of authors who did not previously have access to form and write acceptable papers."In astronomy -- where the core journals are few and a closed circle, and all active researchers have access to them. But this is not true of research as a whole, across disciplines (or around the world). Researchers in most fields are no doubt handicapped for having less than full access, but that does not prevent them from doing and publishing research altogether.

"Any statistical analysis of the causal/bias distinction must take into account the actual distribution of citations among articles. This is why I made the monte carlo analysis in the IPM paper. As a quick example for papers published in the Astrophysical Journal in 2003: The most cited 10% have 39% of all citations, and are 96% in the arXiv; the lowest cited 10% have 0.7% of all citations and are 29% in the arXiv. Showing the causal hypothesis is true will be very difficult under these conditions."(i) Since all of the published postprints in all these journals are accessible to all research-active astronomers as of their date of publication, we are of necessity speaking here mostly about an Early Access effect (preprints). Most of the other components of the Open Access Advantage (Competitive Advantage, Usage Advantage, Quality Advantage) are minimized here by the fact that everything in astronomy is OA from the date of publication onward. The remaining components are either Arxiv-specific (the Arxiv Bias -- the tradition of archiving and hence searching in one central repository) or self-selection [Quality Bias] influencing who does and does not self-archive early, with their prepublication preprint.

Since most fields don't post pre-refereeing preprints at all, this comparison is mostly moot. For most fields, the question about citation advantage concerns the postprint only, and as of the date of acceptance for publication, not before.

(ii) In other fields too, there is the very same correlation between citation counts and percentage self-archived, but it is based on postprints, self-archived at publication, not pre-refereeing preprints self-archived much earlier. And, most important, it is not true in these fields that the postprint is accessible to all researchers via subscription: Many potential users cannot access the article at all if it is not self-archived -- and that is the main basis for the OA impact advantage.

"Perhaps the journal which is most sensitive to cancellations due to OA archiving is Nuclear Physics B; it is 100% in arXiv, and is very expensive. I have several times seen librarians say that they would like to cancel it. One effect of OA on Nuclear Physics B is that its impact factor (as we measure it, I assume ISI gets the same thing) has gone up, just as we show in the J E Pub paper for Physical Review D. Whether Nuclear Physics B has been cancelled more than Nuclear Physics A or Physics Letters B must be well known at Elsevier."It is an interesting question whether NPB is being cancelled, but if it is, it clearly is not because of self-archiving, nor because of astronomy's special "universal paid OA" OA to the published version: if NPB is being cancelled, it is for the usual reason, which is that it is not good enough to justify its share of the institution's journal budget.

Harnad, S. (2005) OA Impact Advantage = EA + (AA) + (QB) + QA + (CA) + UAStevan Harnad

American Scientist Open Access Forum

Thursday, March 30. 2006

Manual Evaluation of Robot Performance in Identifying Open Access Articles

Update Jan 1, 2010: See Gargouri, Y; C Hajjem, V Larivière, Y Gingras, L Carr,T Brody & S Harnad (2010) “Open Access, Whether Self-Selected or Mandated, Increases Citation Impact, Especially for Higher Quality Research”

Update Feb 8, 2010: See also "Open Access: Self-Selected, Mandated & Random; Answers & Questions"

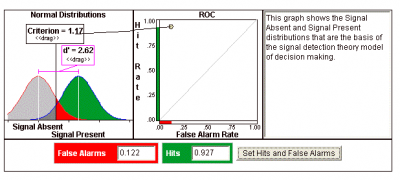

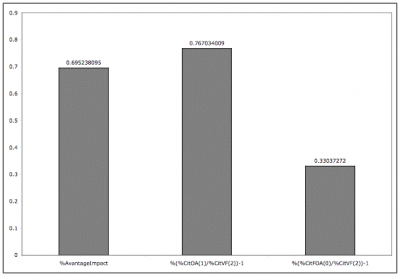

In an unpublished study, Antelman et al. (2005) hand-tested the accuracy of the algorithm that Hajjem et al.'s (2005) software robot used to identify Open Access (OA) and Non-Open-Access (NOA) articles in the ISI database. Antelman et al. found much lower accuracy (d' 0.98, bias 0.78, true OA 77%, false OA 41%), with their larger sample of nearly 600 (half OA, half NOA) in Biology (and even lower, near-chance performance in Sociology, sample size 600, d' 0.11, bias 0.99, true OA 53% false OA 49%) compared to Hajjem et al., who had with their smaller Biology sample of 200, found: d' 2.45, beta 0.52, true OA 93%, false OA 16%.Summary: Antelman et al. (2005) hand-tested the accuracy of the algorithm that Hajjem et al.'s (2005) software robot used to to trawl the web and automatically identify Open Access (OA) and Non-Open-Access (NOA) articles (references derived from the ISI database). Antelman et al. found much lower accuracy than Hajjem et al. Had reported. Hajjem et al. have now re-done the hand-testing on a larger sample (1000) in Biology, and demonstrated that Hajjem et al.'s original estimate of the robot's accuracy was much closer to the correct one. The discrepancy was because both Antelman et al. And Hajjem et al had hand-checked a sample other than the one the robot was sampling. Our present sample, identical with what the robot saw, yielded: d' 2.62, bias 0.68, true OA 93%, false OA 12%. We also checked whether the OA citation advantage (the ratio of the average citation counts for OA articles to the average citation counts for NOA articles in the same journal/issue) was an artifact of false OA: The robot-based OA citation Advantage of OA over NOA for this sample [(OA-NOA)/NOA x 100] was 70%. We partitioned this into the ratio of the citation counts for true (93%) OA articles to the NOA articles versus the ratio of the citation counts for the false (12%) "OA" articles. The "false OA" advantage for this 12% of the articles was 33%, so there is definitely a false OA Advantage bias component in our results. However, the true OA advantage, for 93% of the articles, was 77%. So in fact, we are underestimating the true OA advantage.Previous AmSci Topic Thread:

"Manual Evaluation of Algorithm Performance on Identifying OA" (Dec 2005)

References cited:

Antelman, K., Bakkalbasi, N., Goodman, D., Hajjem, C. and Harnad, S. (2005) Evaluation of Algorithm Performance on Identifying OA. Technical Report, North Carolina State University Libraries, North Carolina State University.

Hajjem, C., Harnad, S. and Gingras, Y. (2005) Ten-Year Cross-Disciplinary Comparison of the Growth of Open Access and How it Increases Research Citation Impact. IEEE Data Engineering Bulletin 28(4) pp. 39-47.

Hajjem et al. have now re-done the hand-testing on a still larger sample (1000) in Biology, and we think we have identified the reason for the discrepancy, and demonstrated that Hajjem et al.'s original estimate of the robot's accuracy was closer to the correct one.

The discrepancy was because Antelman et al. were hand-checking a sample other than the one the robot was sampling: The templates are the ISI articles. The ISI bibliographic data (author, title, etc.) for each article is first used to automatically trawl the web with search engines looking for hits, and then the robot applies its algorithm to the first 60 hits, calling the article "OA" if the algorithm thinks it has found at least one OA full-text among the 60 hits sampled, and NOA if it does not find one.

Antelman et al. did not hand-check these same 60 hits for accuracy, because the hits themselves were not saved; the only thing recorded was the robot's verdict on whether a given article was OA or NOA. So Antelman et al. generated another sample -- with different search engines, on a different occasion -- for about 300 articles that the robot had previously identified as having an OA version in its sample, and 300 for which it had not found an OA version in its sample; Antelman et al.'s hand-testing found much lower accuracy.

Hajjem et al.'s first test of the robot's accuracy made the very same mistake of hand-checking a new sample instead of saving the hits, and perhaps it yielded higher accuracy only because the time difference between the two samples was much smaller (but the search engines were again not the same ones used). Both accuracy hand-tests were based on incommensurable samples.

Testing the robot's accuracy in this way is analogous to testing the accuracy of an instant blood test for the presence of a disease in a vast number of villages by testing a sample of 60 villagers in each (and declaring the disease to be present in the village (OA) if a positive case is detected in the sample of 60, NOA otherwise) and then testing the accuracy of the instant test against a reliable incubated test, but doing this by picking another sample of 60 from 100 of the villages that had previously been identified as "OA" based on the instant test and 100 that had been identified as "NOA." Clearly, to test the accuracy of the first, instant test, the second test ought to have been performed on the very same individuals on which the first test had been performed, not on another sample based only on the overall outcome of the first test, at the whole-village level.

So when we hand-checked the actual hits (URLs) that the robot had identified as "OA" or "NOA" in our Biology sample of 1000, saving all the hits this time, the robot's accuracy was again much higher: d' 2.62, bias 0.68, true OA 93%, false OA 12%.

All this merely concerned the robot's accuracy in detecting true OA. But our larger hand-checked sample now also allowed us to check whether the OA citation advantage (the ratio of the average citation counts for OA articles to the average citation counts for NOA articles in the same journal/issue) was an artifact of false OA:

We accordingly had the robot's estimate of the OA citation Advantage of OA over NOA for this sample [(OA-NOA)/NOA x 100 = 70%], and we could now partition this into the ratio of the citation counts for true (93%) OA articles to the NOA articles (false NOA was very low, and would have worked against an OA citation advantage) versus the ratio of the citation counts for the false (12%) "OA" articles. The "false OA" advantage for this 12% of the articles was 33%, so there is definitely a false OA Advantage bias component in our results. However, the true OA advantage, for 93% of the articles, was 77%. So in fact, we are underestimating the OA advantage.

As explained in previous postings on the American Scientist topic thread, the purpose of the robot studies is not to get the most accurate possible estimate of the current percentage of OA in each field we study, nor even to get the most accurate possible estimate of the size of the OA citation Advantage. The advantage of a robot over much more accurate hand-testing is that we can look at a much larger sample, and faster -- indeed, we can test all of the articles in all the journals in each field in the ISI database, across years. Our interest at this point is in nothing more accurate than a rank-ordering of %OA as well as %OA citation Advantage across fields and years. We will nevertheless tighten the algorithm a little; the trick is not to make the algorithm so exacting for OA as to make it start producing substantially more false NOA errors, thereby weakening its overall accuracy for %OA as well as %OA advantage.

Stevan Harnad & Chawki Hajjem

« previous page

(Page 4 of 4, totaling 36 entries)

EnablingOpenScholarship (EOS)

Quicksearch

Syndicate This Blog

Materials You Are Invited To Use To Promote OA Self-Archiving:

Videos:

audio WOS

Wizards of OA -

audio U Indiana

Scientometrics -