Quicksearch

Your search for double returned 140 results:

Monday, September 17. 2012

Disambiguating RCUK's Open Access Policy Statement

For those with patience for logic, here is how the ambiguity crept into the RCUK Open Access Policy, where it resides, and why it is all the more important to set it right promptly, before it takes root:

The Two Tweaks Needed

to Disambiguate RCUK OA Policy

The Research Councils will recognise a journal as being compliant with their policy on Open Access if:1. [GOLD] The journal provides via its own website immediate and unrestricted access to the publisher’s final version of the paper (the Version of Record), and allows immediate deposit of the Version of Record in other repositories without restriction on re-use. This may involve payment of an ‘Article Processing Charge’ (APC) to the publisher. The CC-BY license should be used in this case..

Or

2. [GREEN] *REMOVE*Where a publisher does not offer option 1 above,*REMOVE* the journal must allow deposit of Accepted Manuscripts that include all changes resulting from peer review (but not necessarily incorporating the publisher’s formatting) in other repositories, without restrictions on non-commercial re-use and within a defined period. In this option no ‘Article Processing Charge’ will be payable to the publisher. Research Councils will accept a delay of no more than six months between on-line publication and a research paper becoming Open Access, except in the case of research papers arising from research funded by the AHRC and the ESRC where the maximum embargo period is 12 months.

ADD: "Where a journal offers both suitable green (2.) and suitable gold (1.) options the PI may choose the option he or she thinks most appropriate"

The RCUK fundee is actually faced with not one but two semi-independent choices to make in order to comply with the RCUK OA mandate: the between-journals choice of a suitable journal, and the within-journal choice of a suitable option.

These two semi-independent choices have been (inadvertently) conflated in the current RCUK policy draft, treating them, ambiguously, as if they were one choice.

Both choices are nominally GREEN versus GOLD choices.

Let's quickly define "GREEN" and "GOLD," because they mean the same in both cases. I will use a definition based on the current RCUK policy draft:

GOLD means the journal makes the article OA with CC-BY ("Libre OA"), usually for a fee.These two definitions are not what is in dispute here.

GREEN means the author makes the article OA ("Gratis OA") by depositing it in a repository, and making it OA within 0-12 months of publication.

But now the GREEN versus GOLD choice applies to two different things:

(1) the author's choice of which journal is an RCUK-suitable journal to publish in (this is the between-journals choice)and then, if the journal offers both the GREEN and GOLD option:

(2) the author's choice of which option to pick (this is the within-journal choice).A perfectly clear and unambiguous way to state the intended policy would be:

An RCUK-suitable journal is one that offersThat would dispel all ambiguity.

(i) GREEN only or (ii) GOLD only or (iii) BOTH (i.e., hybrid GREEN+GOLD).

An RCUK author may choose (i), (ii) or (iii).

If the choice is (iii), the RCUK author may choose GREEN or GOLD.

But what the current RCUK policy actually states instead is:

An RCUK-suitable journal is one that offers (i) GOLD, or, if it does not offer GOLD, then an RCUK-suitable journal is one that offers (ii) GREEN OA.The possibility that the journal offers (iii) both (i.e., hybrid GREEN+GOLD) is not mentioned, and the between-journals choice of journal is hence left completely conflated with the within-journal choice of option.

So the conclusion the RCUK fundee draws is that GREEN can only be chosen if GOLD is not offered: "GREEN IF AND ONLY IF NOT GOLD."

When a policy so fully conflates two distinct, independent choice factors, it is extremely important to disambiguate it so as to undo the conflation.

Dropping the 9-word -- and completely unnecessary -- clause

"Where a publisher does not offer option 1 above" [i.e., does not offer GOLD]would remove the conflation and the ambiguity.

To make this even more transparent, the statement from Mark Thorley, interviewed by Peter Suber, could also be added:

"Where a journal offers both suitable green (2.) and suitable gold (1.) options" [i.e., hybrid GREEN+GOLD] , "the PI may choose the option he or she thinks most appropriate"This would make it perfectly clear that if a hybrid GREEN+GOLD journal is chosen, the author is free to choose either its GREEN or GOLD option.

It is not clear why the clause "Where a publisher does not offer option 1 above" was ever inserted in the first place, as the logic of what is intended is perfectly clear without it, and is only obscured by inserting it.

(The only two conceivable reasons I can think of for that gratuitous and misleading clause's having been inserted in the first place are that either (a) the drafters half-forgot about the hybrid GREEN+GOLD possibility, or (b) they were indeed trying to push authors (and publishers!) toward the GOLD option in both choices: the between-journal choice of GOLD versus GREEN journal and the within-journal choice of the GOLD versus GREEN option -- possibly because of Gold Fever induced by BIS's Finch Folly.)

The RCUK OA Policy can be fixed very easily (and without any fanfare) by doing the two tweaks highlighted at the beginning of this posting -- the first for disambiguation, the second for clarification.

Once that is done, we can all unite in support of the RCUK policy and do everything we can to make it succeed. (There is still a lot of work to do in the implementation details, to provide a reliable fundee-compliance-assurance mechanism.)

If these two essential tweaks were not made, however, then the RCUK OA policy would not only fail (because of author resistance to constraints on journal choice, resentment at the diversion of scarce research funds to double-pay publishers, and outrage at the prospect of having to use their own funds when the RCUK subsidy is insufficient): It would also handicap OA policies by funders and institutions all over the world, by giving publishers worldwide the strong incentive to offer hybrid Gold OA (which, for publishers, is merely a license change, for each individual double-paid article) and -- to maximize the chances of increasing their total revenues by a potential 6% (the UK share) at the expense of UK tax-payers and research funds -- lengthen their Green OA embargoes beyond RCUK limits to make sure UK authors must choose paid Gold.

The failed RCUK policy would not only mean that the UK fails to provide OA to its own research output, but it would make it harder for the rest of the world to mandate and provide (Green) OA to the remaining 94% of worldwide research output. The perverse effects of the UK's colossal false start would hence be both local and global.

Thursday, September 13. 2012

The UK's 6% Factor and the "Gold Trumps Green" Principle: Perverse Effects

[Note: I am using very approximate estimates here, but, within an order of magnitude, they give a much-needed sense of the proportions, if not the exact amounts involved.]

If the Finch/RCUK OA Policy is not revised, worldwide publishers' subscription revenues stand to increase by c. 6% (the approximate UK percentage of all annual peer-reviewed research published) over and above current global subscription revenues, at the expense of the UK taxpayer and UK research, in exchange for Gold OA to UK research output.

If the Finch/RCUK OA Policy is not revised, worldwide publishers' subscription revenues stand to increase by c. 6% (the approximate UK percentage of all annual peer-reviewed research published) over and above current global subscription revenues, at the expense of the UK taxpayer and UK research, in exchange for Gold OA to UK research output.

(This essentially amounts to the author's buying back a copyright license from a hybrid subscription/Gold publisher, in exchange for c. $1000 per article for c. 60,000* articles per year, while letting the publisher continue to sell the article as part of the journal's subscription content. The c. $1000 per article hybrid Gold OA fee is approximately 1/Nth of total worldwide subscription revenue for journals publishing N articles per year.)

I don't know how much the UK as a whole is paying currently for subscriptions. If the UK publishes 6% of worldwide research, perhaps we can assume it pays 6% of publishers' worldwide subscription revenues (if the UK consumes about the same amount as it produces), hence another 60 million dollars.

If so, that means that paying pre-emptively for Gold OA for all UK research output approximately doubles what the UK is paying for publication. (And even if publishers make good on their promise to translate their double-dipping hybrid Gold revenues into proportionate reductions in their worldwide subscription rates, for the UK that only means a 6% rebate on the 100% surcharge that the UK alone pays to make its own output Gold OA -- i.e., $36 million back on a total UK expenditure of $60 million for subscriptions + $60 million for pre-emptive Gold OA license buy-backs.)

And it gets worse: The UK can't cancel its subscriptions, because UK researchers still need access to the other 94% of annual research worldwide.

Nor is that all: By (1) giving subscription publishers the incentive to offer a hybrid Gold OA option (in exchange for 6% more revenue at virtually no added cost to the publisher, since CC-BY is simply a license!) as well as (2) giving subscription publishers the incentive to increase the embargo length on the Green option (cost-free for authors), Finch/RCUK's "Gold trumps Green" policy also denies UK (and worldwide) researchers access to what could have been Green OA research from the rest of the world (94%) for those institutions and individuals in the UK and worldwide who cannot afford subscription access to the journal in which articles they may need are published.

Nor is that all: By (1) giving subscription publishers the incentive to offer a hybrid Gold OA option (in exchange for 6% more revenue at virtually no added cost to the publisher, since CC-BY is simply a license!) as well as (2) giving subscription publishers the incentive to increase the embargo length on the Green option (cost-free for authors), Finch/RCUK's "Gold trumps Green" policy also denies UK (and worldwide) researchers access to what could have been Green OA research from the rest of the world (94%) for those institutions and individuals in the UK and worldwide who cannot afford subscription access to the journal in which articles they may need are published.

And the perverse effects of RCUK's "Gold trumps Green" policy also make it harder for institutions and funders worldwide to adopt Green OA mandates, thereby reducing the potential for worldwide Green OA (which is to say, worldwide OA) still further.

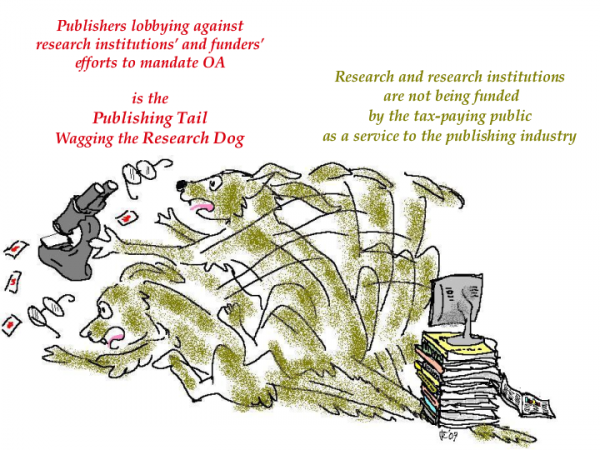

And that suits subscription publishers just fine! It's win/win for them, just so long as funders and institutions don't mandate Green.

That's why subscription publishers lobbied so hard for the Finch/RCUK outcome -- and applauded it as a step in the right direction when it was announced.

What is more of a head-shaker is that "pure" Gold OA publishers lobbied for "Gold trumps Green" too, hoping it would drive more business their way (or, to be fairer, hoping it would force subscription publishers to convert to pure Gold).

What is more of a head-shaker is that "pure" Gold OA publishers lobbied for "Gold trumps Green" too, hoping it would drive more business their way (or, to be fairer, hoping it would force subscription publishers to convert to pure Gold).

But the only thing the promise of Finch/RCUK's Grand Gold Subsidy (6%) actually does is inspire subscription publishers to create a hybrid Gold option (cost-free to them) and to stretch embargoes beyond RCUK's allowable limits, to make sure RCUK authors who wish to keep publishing with them pick and pay for the Gold option (whether or not RCUK gives them enough of the funds BIS co-opted from the UK research budget to pay for it all), rather than the cost-free Green option (which Gold trumps).

Ceterum censeo...: But all these perverse effects can be eliminated by simply striking 9 words from the RCUK policy, making the Gold and Green options equally permissible ways of complying.

Ceterum censeo...: But all these perverse effects can be eliminated by simply striking 9 words from the RCUK policy, making the Gold and Green options equally permissible ways of complying.

Apart from that, what is needed is to shore up the RCUK mandate's compliance verification mechanism. See: "United Kingdom's Open Access Policy Urgently Needs a Tweak" (appears in D-Lib tomorrow, Friday, September 14).

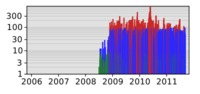

*The percentage of all peer-reviewed journals indexed by Ulrichs that are "pure" (not hybrid) Gold is about 13%, using the numbers in DOAJ. An analysis of the Thomson-Reuters-ISI subset of all articles published in 2007-2011 with a UK affiliation for the first author yielded 324,587 UK articles (65K/year) of which 13,260 articles (3K/year) (4%) were published in pure Gold OA journals -- i.e., not double-dipping hybrid subscription Gold journals.

If the Finch/RCUK OA Policy is not revised, worldwide publishers' subscription revenues stand to increase by c. 6% (the approximate UK percentage of all annual peer-reviewed research published) over and above current global subscription revenues, at the expense of the UK taxpayer and UK research, in exchange for Gold OA to UK research output.

If the Finch/RCUK OA Policy is not revised, worldwide publishers' subscription revenues stand to increase by c. 6% (the approximate UK percentage of all annual peer-reviewed research published) over and above current global subscription revenues, at the expense of the UK taxpayer and UK research, in exchange for Gold OA to UK research output. (This essentially amounts to the author's buying back a copyright license from a hybrid subscription/Gold publisher, in exchange for c. $1000 per article for c. 60,000* articles per year, while letting the publisher continue to sell the article as part of the journal's subscription content. The c. $1000 per article hybrid Gold OA fee is approximately 1/Nth of total worldwide subscription revenue for journals publishing N articles per year.)

I don't know how much the UK as a whole is paying currently for subscriptions. If the UK publishes 6% of worldwide research, perhaps we can assume it pays 6% of publishers' worldwide subscription revenues (if the UK consumes about the same amount as it produces), hence another 60 million dollars.

If so, that means that paying pre-emptively for Gold OA for all UK research output approximately doubles what the UK is paying for publication. (And even if publishers make good on their promise to translate their double-dipping hybrid Gold revenues into proportionate reductions in their worldwide subscription rates, for the UK that only means a 6% rebate on the 100% surcharge that the UK alone pays to make its own output Gold OA -- i.e., $36 million back on a total UK expenditure of $60 million for subscriptions + $60 million for pre-emptive Gold OA license buy-backs.)

And it gets worse: The UK can't cancel its subscriptions, because UK researchers still need access to the other 94% of annual research worldwide.

Nor is that all: By (1) giving subscription publishers the incentive to offer a hybrid Gold OA option (in exchange for 6% more revenue at virtually no added cost to the publisher, since CC-BY is simply a license!) as well as (2) giving subscription publishers the incentive to increase the embargo length on the Green option (cost-free for authors), Finch/RCUK's "Gold trumps Green" policy also denies UK (and worldwide) researchers access to what could have been Green OA research from the rest of the world (94%) for those institutions and individuals in the UK and worldwide who cannot afford subscription access to the journal in which articles they may need are published.

Nor is that all: By (1) giving subscription publishers the incentive to offer a hybrid Gold OA option (in exchange for 6% more revenue at virtually no added cost to the publisher, since CC-BY is simply a license!) as well as (2) giving subscription publishers the incentive to increase the embargo length on the Green option (cost-free for authors), Finch/RCUK's "Gold trumps Green" policy also denies UK (and worldwide) researchers access to what could have been Green OA research from the rest of the world (94%) for those institutions and individuals in the UK and worldwide who cannot afford subscription access to the journal in which articles they may need are published.And the perverse effects of RCUK's "Gold trumps Green" policy also make it harder for institutions and funders worldwide to adopt Green OA mandates, thereby reducing the potential for worldwide Green OA (which is to say, worldwide OA) still further.

And that suits subscription publishers just fine! It's win/win for them, just so long as funders and institutions don't mandate Green.

That's why subscription publishers lobbied so hard for the Finch/RCUK outcome -- and applauded it as a step in the right direction when it was announced.

What is more of a head-shaker is that "pure" Gold OA publishers lobbied for "Gold trumps Green" too, hoping it would drive more business their way (or, to be fairer, hoping it would force subscription publishers to convert to pure Gold).

What is more of a head-shaker is that "pure" Gold OA publishers lobbied for "Gold trumps Green" too, hoping it would drive more business their way (or, to be fairer, hoping it would force subscription publishers to convert to pure Gold). But the only thing the promise of Finch/RCUK's Grand Gold Subsidy (6%) actually does is inspire subscription publishers to create a hybrid Gold option (cost-free to them) and to stretch embargoes beyond RCUK's allowable limits, to make sure RCUK authors who wish to keep publishing with them pick and pay for the Gold option (whether or not RCUK gives them enough of the funds BIS co-opted from the UK research budget to pay for it all), rather than the cost-free Green option (which Gold trumps).

Ceterum censeo...: But all these perverse effects can be eliminated by simply striking 9 words from the RCUK policy, making the Gold and Green options equally permissible ways of complying.

Ceterum censeo...: But all these perverse effects can be eliminated by simply striking 9 words from the RCUK policy, making the Gold and Green options equally permissible ways of complying.Apart from that, what is needed is to shore up the RCUK mandate's compliance verification mechanism. See: "United Kingdom's Open Access Policy Urgently Needs a Tweak" (appears in D-Lib tomorrow, Friday, September 14).

*The percentage of all peer-reviewed journals indexed by Ulrichs that are "pure" (not hybrid) Gold is about 13%, using the numbers in DOAJ. An analysis of the Thomson-Reuters-ISI subset of all articles published in 2007-2011 with a UK affiliation for the first author yielded 324,587 UK articles (65K/year) of which 13,260 articles (3K/year) (4%) were published in pure Gold OA journals -- i.e., not double-dipping hybrid subscription Gold journals.

Friday, June 29. 2012

Why the UK Should Not Heed the Finch Report

Note added since posting:

Fortunately, all the UK Research Funding Councils (RCUK), contrary to the recommendation of the Finch Committee, have now re-affirmed their commitment to continue mandating Green OA, and have even cut the allowable embargo period down to 6 months.

The UK’s universities and research funders have been leading the rest of the world in the movement toward Open Access (OA) to research with “Green” OA mandates requiring researchers to self-archive their journal articles on the web, free for all. A report has emerged from the Finch committee that looks superficially as if it were supporting OA, but is strongly biased in favor of the interests of the publishing industry over the interests of UK research. Instead of recommending building on the UK’s lead in cost-free Green OA, the committee has recommended spending a great deal of extra money to pay publishers for “Gold” OA publishing. If the Finch committee were heeded, the UK would lose both its lead in OA and a great deal of public money -- and worldwide OA would be set back at least a decade.

The UK’s universities and research funders have been leading the rest of the world in the movement toward Open Access (OA) to research with “Green” OA mandates requiring researchers to self-archive their journal articles on the web, free for all. A report has emerged from the Finch committee that looks superficially as if it were supporting OA, but is strongly biased in favor of the interests of the publishing industry over the interests of UK research. Instead of recommending building on the UK’s lead in cost-free Green OA, the committee has recommended spending a great deal of extra money to pay publishers for “Gold” OA publishing. If the Finch committee were heeded, the UK would lose both its lead in OA and a great deal of public money -- and worldwide OA would be set back at least a decade.Open Access (OA). Open Access means online access to peer-reviewed research, free for all. (Some OA advocates want more than this, but all want at least this.) Subscriptions restrict research access to users at institutions that can afford to subscribe to the journal in which the research was published. OA makes it accessible to all would-be users. This maximizes research uptake, usage, applications and progress, to the benefit of the tax-paying public that funds it.

Green and Gold OA. There are two ways for authors to make their research OA. One way is to publish it in an OA journal, which makes it free online. This is called “Gold OA.” There are currently about 25,000 peer-reviewed journals, across all disciplines, worldwide. Most of them (about 90%) are not Gold. Some Gold OA journals (mostly overseas national journals) cover their publication costs from subscriptions or subsidies, but the international Gold OA journals charge the author an often sizeable fee (£1000 or more).

The other way for authors to make their research OA is to publish it in the suitable journal of their choice, but to self-archive their peer-reviewed final draft in their institutional OA repository to make it free online for those who lack subscription access to the publisher’s version of record. This is called “Green OA.”

UK Leadership in Mandating Green OA. The UK is the country that first began mandating (i.e., requiring) that its researchers provide Green OA. Only Green OA can be mandated, because Gold OA costs extra money and restricts authors’ journal choice. But Gold OA can be recommended, where suitable, and funds can be offered to pay for it, if available.

The first Green OA mandate in the world was designed and adopted in the UK (University of Southampton School of Electronics and Computer Science, 2003) and the UK was the first nation in which all RCUK research funding councils have mandated Green OA. The UK already has 26 institutional mandates and 14 funder mandates, more than any other country except the US, which has 39 institutional mandates and 4 funder mandates -- but the UK is far ahead of the US relative to its size (although the US and EU are catching up, following the UK’s lead).

Optimizing Green OA Mandates and Accelerating Adoption.To date, the world has a total of 185 institutional mandates and 52 funder mandates. This is still only a tiny fraction of the world’s total number of universities, research institutes and research funders. Universities and research institutions are the universal providers of all peer-reviewed research, funded and unfunded, across all disciplines, but even in the UK, far fewer than half of the universities have as yet mandated OA, and only a few of the UK’s OA mandates are designed to be optimally effective. Nevertheless, the current annual Green OA rate for the UK (40%) is twice the worldwide baseline rate (20%).

What is clearly needed now in the UK (and worldwide) is to increase the number of Green OA mandates by institutions and funders to 100% and to upgrade the sub-optimal mandates to ensure 100% compliance. This increase and upgrade is purely a matter of policy; it does not cost any extra money.

Gold OA. What is the situation for Gold OA? The latest estimate for worldwide Gold OA is 12%, but this includes the overseas national journals for which there is less international demand. Among the 10,000 journals indexed by Thomson-Reuters, about 8% are Gold. The percentage of Gold OA in the UK is half as high (4%) as in the rest of the world, almost certainly because of the cost and choice constraint of Gold OA and the fact that the UK’s 40% cost-free Green OA rate is double the global 20% baseline, because of the UK’s mandates.

Publisher Lobbying and the Finch Report. Now we come to the heart of the matter. Publishers lobby against Green OA and Green OA mandates on the basis of two premises: (#1) that Green OA is inadequate for users’ needs and (#2) that Green OA is parasitic, and will destroy both journal publishing and peer review if allowed to grow: If researchers, their funders and their institutions want OA, let them pay instead for Gold OA.

Both these arguments have been accepted, uncritically, by the Finch Committee, which, instead of recommending the cost-free increasing and upgrading of the UK’s Green OA mandates has instead recommended increasing public spending by £50-60 million yearly to pay for more Gold OA.

Green OA: Useless? Let me close by looking at the logic and economics underlying this recommendation that publishers have welcomed so warmly: What seems to be overlooked is the fact that worldwide institutional subscriptions are currently paying the cost of journal publishing, including peer review, in full (and handsomely) for the 90% of journals that are non-OA today. Hence the publication costs of the Green OA that authors are providing today are fully paid for by the institutions worldwide that can afford to subscribe.

If publisher premise #1 -- that Green OA is inadequate for users’ needs -- is correct, then when Green OA is scaled up to 100% it will continue to be inadequate, and the institutions that can afford to subscribe will continue to cover the cost of publication, and premise #2 is refuted: Green OA will not destroy publication or peer review.

Or Destructive Parasite? Now suppose that premise #1 is wrong: Green OA (the author’s peer-reviewed final draft) proves adequate for all users’ needs, so once the availability of Green OA approaches 100% for their users, institutions cancel their journals, making subscriptions no longer sustainable as the means of covering the costs of peer-reviewed journal publication.

What will journals do, as their subscription revenues shrink? They will do what all businesses do under those conditions: They will cut unnecessary costs. If the Green OA version is adequate for users, that means both the print edition and the online edition of the journal (and their costs) can be phased out, as there is no longer a market for them. Nor do journals have to do the access-provision or archiving of peer-reviewed drafts: that’s offloaded onto the distributed global network of Green OA institutional repositories. What’s left for peer-reviewed journals to do?

Peer review itself is done for publishers for free by researchers, just as their papers are provided to publishers for free by researchers. The journals manage the peer review, with qualified editors who select the peer reviewers and adjudicate the reviews. That costs money, but not nearly as much money as is bundled into journal publication costs, and hence subscription prices, today.

But if and when global Green OA “destroys” the subscription base for journals as they are published today, forcing journals to cut obsolete costs and downsize to just peer-review service provision alone, Green OA will by the same token also have released the institutional subscription funds to pay the downsized journals’ sole remaining publication cost – peer review – as a Gold OA publication fee, out of a fraction of the institutional windfall subscription savings. (And the editorial boards and authorships of those journal titles whose publishers are not interested in staying in the scaled down post-Green-OA publishing business will simply migrate to Gold OA publishers who are.)

So, far from leading to the destruction of journal publishing and peer review, scaling up Green OA mandates globally will generate, first, the 100% OA that research so much needs -- and eventually also a transition to sustainable post-Green-OA Gold OA publishing.

But not if the Finch Report is heeded and the UK heads in the direction of squandering more scarce public money on funding pre-emptive Gold OA instead of extending and upgrading cost-free Green OA mandates.

Saturday, June 2. 2012

Elsevier's Public Image Problem

"Horizon 2020:

A €80 Billion Battlefield for Open Access"

an article in AAAS's ScienceInsider which notes that:

"Elsevier's embargoes for green open access currently range from 12 to 48 months"First, it has to be clearly understood that the existing EU mandate (i.e., requirement) that the EU is now proposing to extend to all of the EU's €80 Billion's worth of funded research -- while something similar is being proposed for adoption in the US by the Federal Research Public Access Act (FRPAA) as well as by the currently ongoing petition to the White House (rapidly nearing the threshold of 25,000 signatories) -- is a mandate for the Green OA self-archiving, by researchers, of the final drafts of articles published in any journal. (What is to be mandated is not Gold OA publishing: You cannot require researchers to publish other than in their journals of choice, nor require them to pay to publish.)

And although some publishers do over-charge, and do lobby against Green OA mandates, the majority of journals (including almost all the top journals) have already formally confirmed that their authors retain the right to self-archive their final drafts immediately upon publication -- not just after an embargo period has elapsed.

Moreover, that majority of journals that have formally endorsed immediate, un-embargoed Green OA include all the journals published by the two biggest journal publishers, Springer and Elsevier! The only difference is that unlike Springer, Elsevier has just recently tried to hedge its author rights-retention policy with a clause to the effect that authors retain the right to self-archive if they wish but not if they must (i.e., not if it is mandated!). (See Elsevier's "Authors' Rights & Responsibilities")

(Curious "right," that one may exercise if one wishes, but not if one must! Imagine if citizens had the right to free speech but not if it is required (e.g., in a court of law). But strange things can be said in contracts...)

Elsevier is having an increasingly severe public image problem: It is already widely resented for its extortionately high prices, hedged with "Big Deals" that sweeten the price package by adding journals you don't want, at no extra charge. Elsevier is also itself the subject of an ongoing boycott petition (with over 10,000 signatories) because of its pricing policy.

So Elsevier cannot afford more mud on its face. Elsevier has accordingly taken a public, formal stance alongside Springer, on the side of the angels regarding Elsevier authors' retained right to do un-embargoed Green OA self-archiving of their final drafts on their institutional websites -- but Elsevier alone has tried to hedge its progressive-looking stance with the clause defining the authors' right to exercise their retained right only if they are not required to exercise it..

Elsevier's cynical attempt to hedge its green rights-retention policy against OA mandates will no doubt be quietly jettisoned once it is publicly exposed for the cynical double-talk it is. Meanwhile, Elsevier authors can continue to exercise their immediate, un-embargoed self-archiving rights, enshrined in Elsevier's current rights agreement, with hand on heart, declaring that they are self-archiving because they wish, not because they must, even if it is mandated. A mandate, after all, can either be complied with or not complied with; both choices are exercises of free will, yet another basic right…

Time for Elsevier to Improve Its Public Image

Under "What rights do I retain as a journal author?", Elsevier's "Authors' Rights & Responsibilities" document formally states that Elsevier authors retain the right to make their final, peer-reviewed drafts Open Access immediately upon publication (no embargo) by posting them on their institutional website (Green Gratis OA):

"[As an Elsevier author you retain] the right to post a revised personal version of the text of the final journal article (to reflect changes made in the peer review process) on your personal or institutional website or server for scholarly purposes"More recently, however, an extra clause has been slipped into this statement of this retained right to self-archive:

"but not in institutional repositories with mandates for systematic postings."The distinction between an institutional website and an institutional repository is bogus.

The distinction between nonmandatory posting (allowed) and mandatory posting (not allowed) is arbitrary nonsense. ("You retain the right to post if you wish but not if you must!")

The "systematic" criterion is also nonsense. (Systematic posting would be the institutional posting of all the articles in the journal. But any single institution only contributes a tiny, arbitrary fraction of the articles in any journal, just as any single author does. So the mandating institution would not be a 3rd-party "free-rider" on the journal's content: Its researchers would simply be making their own articles OA, by posting them on their institutional website, exactly as described.)

This "systematic" clause is hence pure FUD, designed to scare or bully or confuse institutions into not mandating posting, and authors into not complying with their institutional mandates. (There are also rumours that in confidential licensing negotiations with institutions, Elsevier has been trying to link bigger and better pricing deals to the institution's agreeing either to allow OA to be embargoed for a year or longer or not to adopt a Green OA mandate at all.)

Along with the majority of publishers today, Elsevier is a Green publisher: Elsevier has endorsed immediate (unembargoed) institutional Green OA posting by its authors ever since 27 May 2004.

Elsevier's public image is so bad today that rescinding its Green light to self-archive after almost a decade of mounting demand for OA is hardly a very attractive or viable option:

And double-talk, smoke-screens and FUD are even less attractive

It will be very helpful -- in making it easier for researchers to provide (and for their institutions and funders to mandate) Open Access -- if Elsevier drops its "you may if you wish but not if you must" clause, which is not only incoherent, but intimidates authors. (This would also help counteract some of the rather bad press Elsevier has been getting lately...)

Stevan Harnad

Monday, May 14. 2012

Elsevier requires institutions to seek Elsevier's agreement to require their authors to exercise their rights?

What rights do I retain as a journal author?

I am grateful to Elsevier's Director for Universal Access, Alicia Wise, for replying about Elsevier's author open access posting policy.

This makes it possible to focus very quickly and directly on the one specific point of contention, because as it stands, the current Elsevier policy is quite explicitly self-contradictory:

ALICIA WISE (AW): "Stevan Harnad has helpfully summarized Elsevier’s posting policy for accepted author manuscripts, but has left out a couple of really important elements.I am afraid this is not at all clear.

"He is correct that all our authors can post voluntarily to their websites and institutional repositories. Posting is also fine where there is a requirement/mandate AND we have an agreement in place. We have a growing number of these agreements."

What does it mean to say that Elsevier has a different policy depending on whether an author is posting voluntarily or mandatorily?

An author who wishes to comply with an institutional posting mandate is posting voluntarily. An author who does not wish to comply with an institutional posting mandate refrains from posting, likewise voluntarily.

The Elsevier policy in question concerns the rights that reside with authors. Is Elsevier proposing that some author rights are based on mental criteria? But if an authors says, hand on heart, "I posted voluntarily" (even where posting is mandatory) is the author not to be believed?

(It is true that in criminal court a distinction is made between the voluntary and involuntary -- but the involuntary there refers to the unintended or accidental: Even in mandated posting, the posting is no accident!)

So it is quite transparent that the factor that Elsevier really has in mind here is not the author's voluntariness at all, but whether or not the author's institution has a mandatory posting policy - and whether that institutional mandate has or has not been "agreed" with Elsevier.

But then what sort of an author right is it, to post if your institution doesn't require you to post, but not to post if your institution requires you to post (except if some sort of "agreement" has been reached with Elsevier that allows the institution to require its researchers to exercise their rights)?

That does not sound like an author right at all. Rather, it sounds like an attempt by Elsevier to redefine the author right so as to prevent each author's institution from requiring the author to exercise it without Elsevier's agreement. By that token, it looks as if the author requires Elsevier's agreement to exercise the right that Elsevier has formally recognized to rest with the author.

(What sort of right would the right to free speech be if one lost that right whenever one was required -- say, by a court of law, or even just an institutional committee meeting -- to exercise it? -- And what does it mean that an author's institution is required by a publisher to seek an agreement from the publisher for its authors to exercise a right that the publisher has formally stated rests with the author?)

AW:We are talking here very specifically about authors posting in their own institutional repositories, not about institution-external deposit or proxy deposit by publishers.

"An overview of our funding body agreements can be read here. These agreements, for example, mean that we post to UKPMC for authors who receive funding from a number of funding agencies including the Wellcome Trust. We deposit manuscripts into PMC for NIH-funded authors."

AW:Is it? So if institutions mandate depositing in Arxiv rather than institutionally, that would be fine too? (Some mandates already specify that as an option.) Or would Elsevier authors lose their right to exercise their right to post in Arxiv if their institutions mandated it...?

"Posting in the arXiv is fine too."

AW:The point under discussion is Elsevier authors' right to exercise the right that Elsevier has formally stated rests with the author -- to post their accepted author manuscripts institutionally. What kind of further agreement is needed from the author's institution with Elsevier in order that the author should have the right to exercise a right that Elsevier has formally stated rests with the author?

"We are also piloting open access agreements with a growing number of institutions, including posting in institutional repositories."

Again, Elsevier's target here is very obviously not author rights at all. Rather, the clause in question is an attempt to influence institutions' own policies, with their own research output, by trying to redefine the author's right to post an article online free for all as being somehow contingent on institutional research posting policy, and hence requiring Elsevier's agreement.

It would seem to me that institutions would do well to refrain from making any agreement with Elsevier (or even entering into discussion with Elsevier) about institutional policy -- other than what price they are willing to pay for what journals (even if Elsevier reps attempt to make a quid-pro-quo deal).

And it would seem to me that Elsevier authors should go ahead and post their accepted author manuscripts in their institutional repositories, voluntarily, exercising the right that Elsevier has formally recognized as resting with the author alone since 2004, and ignore any new clause that contains double-talk trying to make a link between the author's right to exercise that author right and the policy of the author's institution on whether or not the author should exercise that right.

AW:I am not sure what this means. Accepted author manuscripts (of journal articles, from all institutions, in all disciplines) fit into all institutional repositories. That's all that's at issue here. No institution differences; no discipline differences.

"It is already clear that one size does not fit all institutions, and we are keen to continue learning, listening, and partnering."

AW:Fortunately, only two details matter (and they can be made explicit without any danger to one's health!):

"Our access policies can be read in full [here] (health warning: they are written for those who really enjoy detail) and we’ve been working on a more friendly and succinct summary too (but this is still a work in "

1. Does Elsevier formally recognize that "all [Elsevier] authors can post [their accepted author manuscripts] voluntarily to their websites and institutional repositories" (quoting from Alicia Wise here)?

According to Elsevier formal policy since 2004, the answer is yes.

2. What about the "not if it is mandatory" clause?

That clause seems to be pure FUD and I strongly urge Elsevier -- for the sake of its public image, which is right now at an all-time low -- to drop that clause rather than digging itself deeper by trying to justify it.

The goal of the strategy is transparent:"We wish to appear to be supportive of open access, formally encoding in our author agreements our authors' right to post their accepted author manuscripts to their institution's open access repository -- but [to ensure that publication remains sustainable,' we wish to prevent institutions from requiring their authors to exercise that right unless they make a side-deal with us."Not a commendable publisher strategy, at a time when the worldwide pressure for open access is mounting ever higher, and subscriptions are still paying the cost of publication, in full, and handsomely.

If there is eventually to be a transition to hybrid or Gold OA publishing, let that transition occur without trying to hold hostage the authors' right to provide Green OA to their author accepted manuscripts by posting them free for all in their institutional repositories, exercising the right that Elsevier has formally agreed rests with the author.

Stevan Harnad

Sunday, May 13. 2012

How Elsevier Can Improve Its Public Image

What rights do I retain as a journal author?

Along with the majority of refereed journal publishers today, Elsevier is a "Green" publisher, meaning Elsevier has formally endorsed immediate (unembargoed) institutional Green OA self-archiving by its authors ever since 27 May 2004.

Recently, however, a new clause has been added to "Authors' Rights and Responsibilities," the document in which Elsevier formally recognizes its authors' right to make their final, peer-reviewed drafts Open Access immediately upon publication (no embargo) by posting them on their institutional website (Green Gratis OA). The new clause is:

"but not in institutional repositories with mandates for systematic postings."The distinction between an institutional website and an institutional repository is bogus.

The distinction between nonmandatory posting (allowed) and mandatory posting (not allowed) is arbitrary nonsense. ("You retain the right to post if you wish but not if you must!")

The "systematic" criterion is also nonsense. (Systematic posting would be the institutional posting of all the articles in the journal; but any single institution only contributes a tiny, arbitrary fraction of the articles in any journal, just as any single author does; so the mandating institution is not a 3rd-party "free-rider" on the journal's content: its researchers are simply making their own articles OA, by posting them on their institutional website, exactly as described.)

This "systematic" clause is hence pure FUD, designed to scare or bully or confuse institutions into not mandating posting, and to scare or bully or confuse authors into not complying with their institutional mandates. (There are also rumours that in confidential licensing negotiations with institutions, Elsevier has been trying to link bigger and better pricing deals to the institution's agreeing not to adopt a Green OA mandate.)

Elsevier's public image is so bad today that rescinding its Green light to self-archive after almost a decade of mounting demand for OA is hardly a very attractive or viable option.

And double-talk, smoke-screens and FUD are even less attractive or viable.

It will hence very helpful in helping researchers to provide -- and their institutions and funders to mandate -- Open Access if Elsevier drops its "you may if you wish but not if you must" clause.

It will also help to improve Elsevier's public image.

Stevan Harnad

Saturday, May 12. 2012

Elsevier's query re: "positive things from publishers that should be encouraged, celebrated, recognized"

What rights do I retain as a journal author?

Alice Wise (Elsevier, Director of Universal Access, Elsevier) asked, on the Global Open Access List (GOAL):

Remedios Melero replied, on GOAL:"[W]hat positive things are established scholarly publishers doing to facilitate the various visions for open access and future scholarly communications that should be encouraged, celebrated, recognized?"

RM: I would recommend the following change in one clause of the What rights do I retain as a journal author? stated in Elsevier's portal, which says:That would be fine. Or even this simpler one would be fine:"the right to post a revised personal version of the text of the final journal article (to reflect changes made in the peer review process) on your personal or institutional website or server for scholarly purposes, incorporating the complete citation and with a link to the Digital Object Identifier (DOI) of the article (but not in subject-oriented or centralized repositories or institutional repositories with mandates for systematic postings unless there is a specific agreement with the publisher. Click here for further information)"RM: By this one:"the right to post a revised personal version of the text of the final journal article (to reflect changes made in the peer review process) on your personal, institutional website, subject-oriented or centralized repositories or institutional repositories or server for scholarly purposes, incorporating the complete citation and with a link to the Digital Object Identifier (DOI) of the article"RM: I think this could be something to be encouraged, celebrated and recognized.

"the right to post a revised personal version of the text of the final journal article (to reflect changes made in the peer review process) on your personal, institutional website or institutional repositories or server for scholarly purposes, incorporating the complete citation and with a link to the Digital Object Identifier (DOI) of the article"The metadata and link can be harvested from the institutional repositories by institution-external repositories or search services, and the shameful, cynical, self-serving and incoherent clause about "mandates for systematic postings" ("you may post if you wish but not if you must"), which attempts to take it all back, is dropped.

That clause -- added when Elsevier realized that Green Gratis OA mandates were catching on -- is a paradigmatic example of the publisher FUD and double-talk that has no legal sense or force, but scares authors (and their management).

Dropping it would be a great cause for encouragement, celebration and recognition, and would put Elsevier irreversibly on the side of the angels (regarding OA).

Stevan Harnad

Tuesday, November 15. 2011

The Liège ORBi model: Mandatory policy without rights retention but linked to assessment procedures

Berlin 9 Open Access policy development Workshop

by:

Bernard Rentier

(Rector, U. Liege)

&

Paul Thirion

(Repository Manager, U. Liege)

PDF OF PRESENTATION

The decision to build an institutional repository at the University of Liège was taken in 2005. It took 3 years to prepare for a faultless start in November 2008. A strong communication campaign conveyed the Open Access concept to the ULg research community. A name was coined to personalise the concept : ORBi (Open Repository and Bibliography), suggesting an improved worldwide audience. A special effort in internal communication was devoted to acceptance of the mandate. It appeared essential to make it plain that ORBi would offer an unprecedented increase in readership, but that it would only be valuable if all ULg members would abide by the new rules.

Any mandate needs some coercitive persuasion. Rather than resting on advocacy, we linked internal assessment to the scientific output stored in ORBi. Those applying for promotion have no choice but to file all their publications in full text.

This created waves of progress.

Since then, evidence for a much increased readership (about double) has transformed the early participants into strong advocates of the repository. 68,000 items have been deposited, 41,000 (60,2%) with full text (only mandatory for documents published later than 2002).According to ROAR, out of 1,568 Institutional Repositories (IRs), ORBi currently comesORBi is now considered a success by almost all ULg faculty. Its advantages to individual authors have become a better incentive than the mandate itself.

27th for total number of deposits,

15th for « high activity level »

(deposit rates for multi-institution IRs) and

1st for « medium activity level »

(deposit rates for single-institution IRs: 10-99 deposits/day).

Thursday, September 8. 2011

Self-Archive Institutionally, Harvest Centrally

In the Hedda Blog, Chris Maloney (Contractor for PubMed Central) asked:

Comments invited -- but please don't post them here but in the Higher EDucation Development Association (HEDDA) blog.

"Assuming the article is in the biomedical field, can authors simultaneously put a copy of their manuscript in their institution’s repository, and upload it to PMC through the NIHMS? Or does the article have to be funded by the NIH for them to do this?… The reason I ask question #2 is that I am wondering if just putting a manuscript [in]to an IR is enough to truly make the article visible and accessible. Just because something’s on the web doesn’t mean it will be found. Just because something’s indexed by Google doesn’t mean it will have high rank in their search results. Putting a manuscript on PMC, through NIHMS or other channels, means that it would be indexed in PubMed, which would make it more accessible."This an extremely important practical issue, and at the moment it is not being properly implemented.

The short answer is, yes, a document deposited in the author's institutional repository (IR) can be uploaded to PMC through NIHMS, regardless of whether NIH has funded the research (and, a fortiori, regardless of whether NIH has funded extra "gold" OA publication fees).

But those extra author self-archiving steps should not be necessary! The reason it became apparent that green OA self-archiving mandates (from both institutions and funders) would be necessary was that spontaneous, unmandated self-archiving rates remain low (about 20%), even when recommended or encouraged by institutions and funders. That's why the first NIH OA policy, a request, failed until it was upgraded to a requirement.

But the practical implementation of the NIH mandate was still short-sighted: It required direct deposit in PMC, and allowed this to be done by either the author or the publisher. The result was not only (1) uncertainty about who needed to deposit what, when, not only (2) a partial reliance on a 3rd party other than the fundee, not bound by the grant, namely, the publisher, to fulfill the conditions of a grant to the fundee, but it also (3) imposed a double burden on fundees if their own institutions were to mandate self-archiving too: They had to deposit in their own IRs and also in PMC.

This did not help either with encouraging more institutions to adopt self-archiving mandates (even though institutions are the universal providers of all research, funded and unfunded, across all disciplines) nor with encouraging authors, already sluggish about self-archiving at all, to comply with self-archiving mandates (since they might be faced with having to deposit the same paper many times).

Yet in reality, the problem is merely a formal one, not a technical one. Software (e.g., SWORD) can import and export the contents of one repository to another automatically. More important: There is no need for institutional authors ever to have to self-archive directly in an institution-external (central) repository like PMC: The contents of IRs are all OAI-compliant and harvestable automatically by whatever central repositories might want them.

So institutional and funder mandates need to be collaborative and convergent, not competitive and divergent, as some (including NIH's) are now. And the convergence needs to be on institution-internal deposit, followed by central harvesting (e.g. to PMC) where desired -- certainly not the reverse.

"Deposit institutionally, harvest centrally." This not only encourages institutions to adopt their own mandates, to complement funder mandates and cover the entire OA target corpus, but it also puts institutions in a position to monitor and ensure compliance with funder mandates. (Ensuring that all funder grant fulfillment conditions are met is something that institutions are always very eager to do!)

(The visibility/accessibility worry is, I think, a red herring: OAI-compliant institutional repositories are harvested by Google, Google Scholar, BASE. citeseerx and many other search engines, including OAI-specific ones. And besides, IR metadata and documents can also be harvested into central repositories like PMC and UK-PMC. The only real factor in visibility and accessibility is whether or not an article has been made green OA at all! Where it is made OA matters little, and it matters less and less as more and more is made OA.)

See:

"How to Integrate University and Funder Open Access Mandates"Summary: Research funder open-access mandates (such as NIH's) and university open-access mandates (such as Harvard's) are complementary. There is a simple way to integrate them to make them synergistic and mutually reinforcing:

Universities' own Institutional Repositories (IRs) are the natural locus for the direct deposit of their own research output: Universities (and research institutions) are the universal research providers of all research (funded and unfunded, in all fields) and have a direct interest in archiving, monitoring, measuring, evaluating, and showcasing their own research assets -- as well as in maximizing their uptake, usage and impact.

Both universities and funders should accordingly mandate deposit of all peer-reviewed final drafts (postprints), in each author's own university IR, immediately upon acceptance for publication, for institutional and funder record-keeping purposes. Access to that immediate postprint deposit in the author's university IR may be set immediately as Open Access if copyright conditions allow; otherwise access can be set as Closed Access, pending copyright negotiations or embargoes. All the rest of the conditions described by universities and funders should accordingly apply only to the timing and copyright conditions for setting open access to those deposits, not to the depositing itself, its locus or its timing.

As a result, (1) there will be a common deposit locus for all research output worldwide; (2) university mandates will reinforce and monitor compliance with funder mandates; (3) funder mandates will reinforce university mandates; (4) legal details concerning open-access provision, copyright and embargoes will be applied independently of deposit itself, on a case by case basis, according to the conditions of each mandate; (5) opt-outs will apply only to copyright negotiations, not to deposit itself, nor its timing; and (6) any central OA repositories can then harvest the postprints from the authors' IRs under the agreed conditions at the agreed time, if they wish.

Comments invited -- but please don't post them here but in the Higher EDucation Development Association (HEDDA) blog.

« previous page

(Page 9 of 14, totaling 140 entries)

» next page

EnablingOpenScholarship (EOS)

Quicksearch

Syndicate This Blog

Materials You Are Invited To Use To Promote OA Self-Archiving:

Videos:

audio WOS

Wizards of OA -

audio U Indiana

Scientometrics -

The American Scientist Open Access Forum has been chronicling and often directing the course of progress in providing Open Access to Universities' Peer-Reviewed Research Articles since its inception in the US in 1998 by the American Scientist, published by the Sigma Xi Society.

The American Scientist Open Access Forum has been chronicling and often directing the course of progress in providing Open Access to Universities' Peer-Reviewed Research Articles since its inception in the US in 1998 by the American Scientist, published by the Sigma Xi Society.

The Forum is largely for policy-makers at universities, research institutions and research funding agencies worldwide who are interested in institutional Open Acess Provision policy. (It is not a general discussion group for serials, pricing or publishing issues: it is specifically focussed on institutional Open Acess policy.)

You can sign on to the Forum here.

Archives

Calendar

|

|

May '21 | |||||

| Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun |

| 1 | 2 | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

| 31 | ||||||

Categories

Blog Administration

Statistics

Last entry: 2018-09-14 13:27

1129 entries written

238 comments have been made