Who were the people who made the amphorae for Portus? The evidence from manufacturing techniques

An understanding of the manufacturing techniques and of the production sequence in terms of how pots are made provides us with an insight into the people making the ceramics. The clay, the raw material, is a plastic additive medium, allowing for traces of its manipulation by the potters, to be left in the finished ceramic product. Fashioning methods, or manufacturing techniques, used in creating a vessel are usually detectable. The traces are permanently embedded within a vessel once the firing stage is complete, meaning that the vessels carry information about the people making them, even if we study ceramics from consumption sites such as Portus.

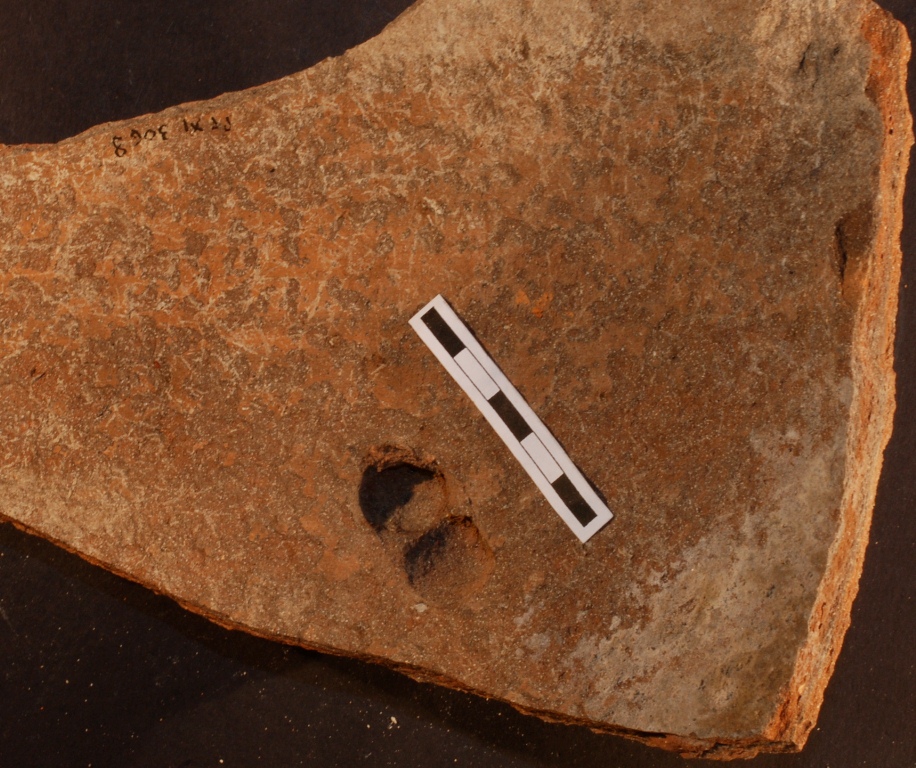

According to academic ceramic literature, knowledge: ‘how we learn and do make things’ (Budden 2007) is socially and culturally based. It is therefore possible to look at technological variables in archaeological ceramics, the types of manufacturing techniques used for instance, to differentiate between archaeological communities. The Tripolitanian (Libyan) amphora handles, for example, are very distinctive. These are pulled and show characteristic finger indentation at the point where they attach the rim-neck or the shoulder in the case of the Tripolitana 2 type. Finger indentation is a characteristic noticed on most all of the Tripolitanian handles (Fig.1).

Different techniques used are indicative of societal aspects, such as organization of production. Having visited a number of traditional pottery workshops in Tunisia, it was apparent that the type of technique used was correlated to the type of pots being produced, to their size in particular, type of workshops, as well as the setting of the workshops, for instance urban versus more rural, and possibly to the relationships between workers (family businesses or more industrial), and finally the type of market which the pots were intended for.

Primary forming techniques can be categorized as being hand made or wheel thrown. However a mixture of techniques existed, and this is especially documented ethnographically in the making of large sized vessels. Coiling is one very common type of hand building. It indicates the creation of a ceramic vessel by adding sausages of clay. However, coiling and shaping of coils on the wheel – wheel shaping – occurs in workshops in southern Tunisia, where they still manufacture large vessels resembling Roman amphorae. While wheel throwing is a very fast technique used for smaller vessels, wheel shaping is much more laborious and time-consuming, and it is used to make large to very large vessels.

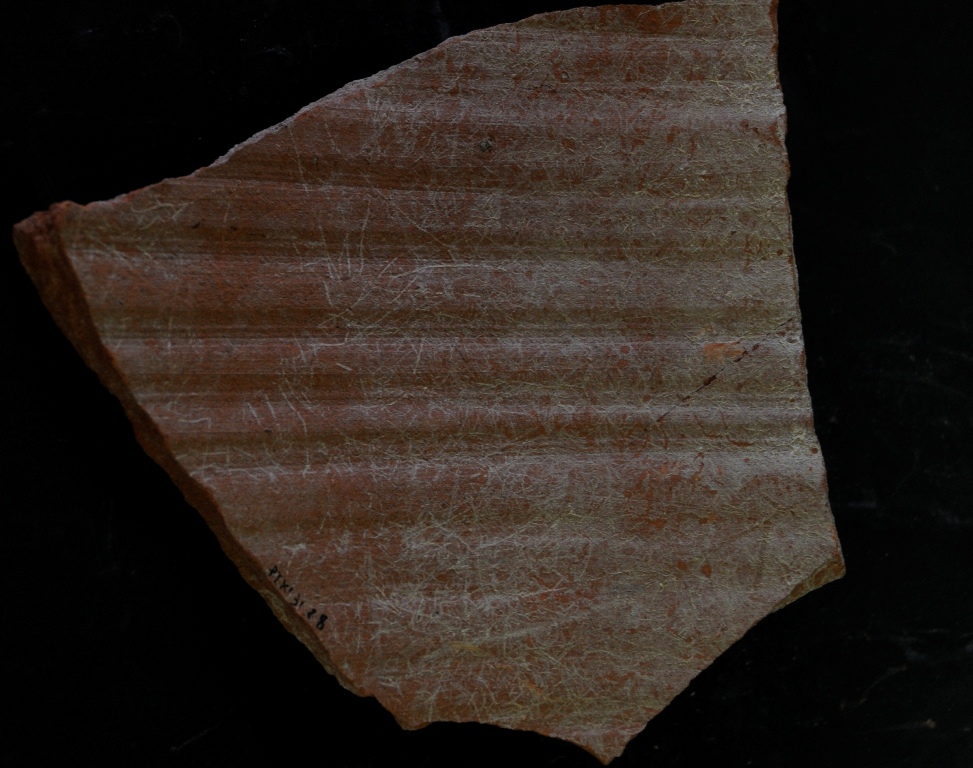

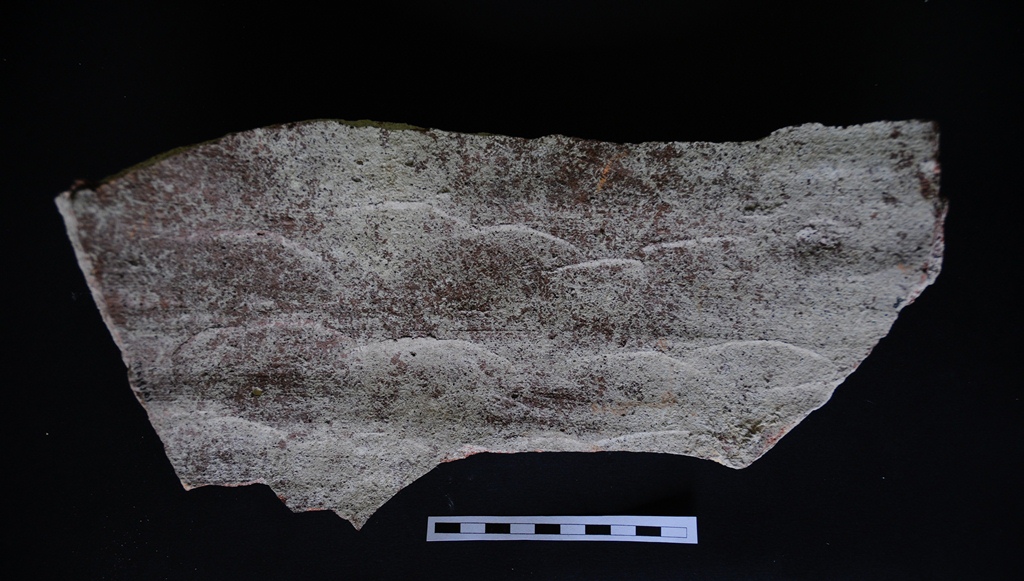

Fashioning techniques can be observed macroscopically. Wheel thrown pots will show characteristic ridges or rilling, which tend to be symmetrical. These are particularly evident inside the vessels (Fig. 2). Instead,wheel-shaping shows rilling which tend to be blurred and also joins of coils (Fig. 3).

The production sequence for the manufacturing of amphorae includes a number of steps, from clay procurement, tempering of the clay with organic or inorganic inclusions, wedging (removing air and unwanted particles from) the clay, building up the ceramic body, adding additional features such as handles, the drying stage and firing.

The wedging of the clay, or preparation of the clay, is an important step, and much attention is given by the potters to such operation. Poor wedging can indeed leave air pockets in the clay, which could cause bubbles in the surface of vessel during the drying and firing stages, compromising the integrity of the vessel. And perhaps leading to the vessel exploding. This skilled and important step of the production sequence is traditionally done using hands or feet (Fig. 4).

Air pockets are particular evident in the Tripolitanian vessels at Portus (Fig. 5).

In terms of the manufacture of amphorae traded with Portus, they were wheel thrown or built up by a combination of coiling and wheel shaping. Working on the amphorae, different technological variables were noticed on Africana 1A and Tripolitanian vessels, two of the most traded vessels represented at Portus with the end 2nd and beginning of the 3rd centuries AD. The first was manufactured in Tunisia while the second was made in Libya. As I was interested in the forming techniques and in understanding the people behind their production, I started photographing the inside of the vessels and recorded a number of technological variables such as types of rilling, the presence or absence of joins of coiling, the degree of skill of execution in the preparation of the clay, and so on. The aim was to gain an insight, from the evidence, about how the different archaeological communities who invested a large amount of skill and labour in supplying Portus, were organized.

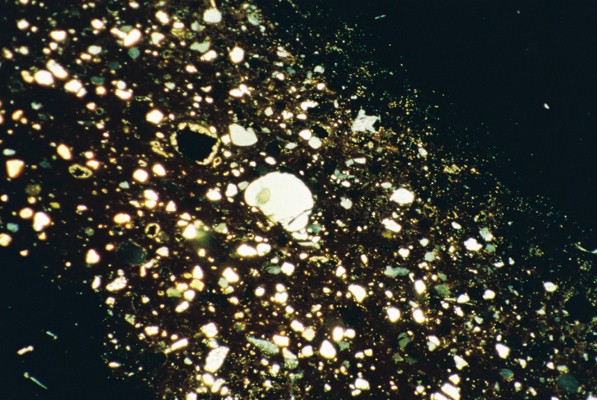

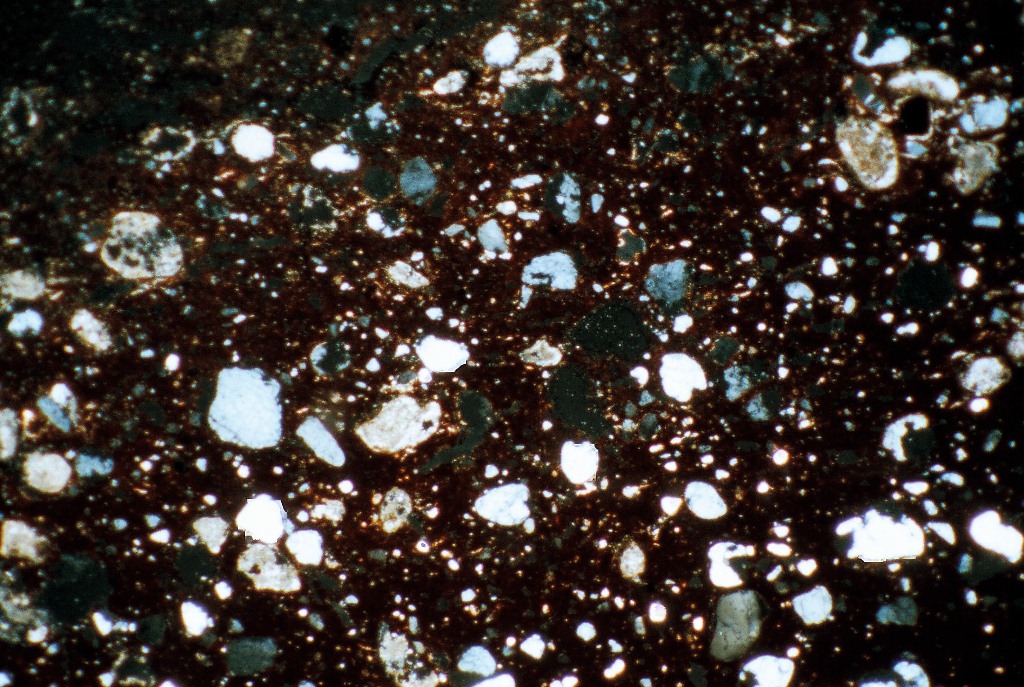

The Africana 1A amphora type according to vessel typology and fabric was mainly traded to Portus from Sullecthum, and a lesser amount from Leptiminus. These are both coastal town ports located in central Tunisia. The vessels show in most of the cases full wheel thrown rilling. Evidence of wheel throwing, is also visible microscopically within the micro fabrics, through means of petrological thin sections (definition of fabrics and petrology are given in my previous blog). Indeed, the clay particles and the inclusions will assume a different orientation according to the manipulation of the raw material and the type of forming technique used. Syllecthum and Leptiminus fabrics show a sort of aligned orientation of the inclusions, which is associated with wheel throwing (Fig. 6, see also the petrological thin section of the Africana 1A in Sullecthum fabric in my previous blog post about ceramics).

Tripolitanian (Libyan) amphorae were built differently. A mixture of hand building and wheel throwing is visible, underlined by compression areas and finger imprints probably necessary to smooth the coils. Such characteristics are very apparent, for example on Tripolitanian vessels in Leptis Magna fabric (Fig. 7). In thin section, the inclusions of the Tripolitanian fabrics appear randomly distributed (Fig. 8). Also, a higher percentage of air pockets were noticed and recorded within the Tripolitanian amphorae (see Fig. 4).

What does this evidence or difference in the technology used suggest? Archaeological studies in North Africa show that the pottery workshops of Sullecthum and Leptiminus were located on the outskirts of the towns; these were semi-urban workshops. Evidence for olive oil production, such as standing olive oil presses, is, on the other hand, more evident inland from the towns. It appears that two specialized and separate economic sectors were going on: the pot-making and agricultural practice. Therefore, people may have specialized in the making of vessels, reaching a high level of skill in mastering the wheel. Studies have attempted to define skill, and one of the definitions is that skill is the outcome of time spent in performing an activity. Moreover, contracts would have existed between those who produced olive oil, those who manufactured the vessels and those who exported produce to Rome. Good, solid batches of amphorae had to be purchased by third parties, and to be filled with olive oil.

In Tripolitania, by contrast, settlement studies show that sites were equipped with oil olive processing facilities and pottery kilns, highlighting the rural and self-sufficient nature of production. All production, from olive oil, to amphora manufacturing, and bottling took place on site. It is very possible that people who harvested the olives, a seasonal job, could have made their own vessels. In this case, manufacturing error such as air pockets noticed on the vessels, did not matter, because there was no necessity to buy containers from a third party.

You might want to look back at the following sections of the Archaeology of Portus course:

- The links to other ports (Portus-1), (Portus-2), (Portus-3)

- The value of ceramics (Portus-1), (Portus-2), (Portus-3)

- Find of the Week – amphora sherds from Leptis Magna (Portus-1), (Portus-2), (Portus-3)

- Scientific Finds Analyses (Portus-1), (Portus-2), (Portus-3)

- Find of the week – fineware (Portus-1), (Portus-2), (Portus-3)

Reference cited in the text:

Budden, S. (2007) Renewal and Reinvention: the role of learning strategies in the Early to Late Middle Bronze Age of the Carpathian Basin. Unpublished PhD thesis. University of Southampton.

More information is contained in Appendix 1: Technology as a Social Tool’ with relevant bibliography on technology and society, in my e-thesis:

(2012) African amphorae from Portus. University of Southampton, School of Humanities, Doctoral Thesis, 864pp.